[This article is fairly long, so you may need to read it on a web browser or in app. Apologies. And if you care about the sales of literary minded fiction, maybe you’ll enjoy my new recently published novel Metallic Realms. Reviews have called the book “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). More info here.]

Ever since I’ve been reading literary novels, they’ve been on their last legs. Literary fiction is perpetually in decline. The novel? Dead so many times its death has been a cliche for a hundred years. There always seems to be a new publisher or tech company coming along with a plan to fix the whole situation… and yet somehow they always fail. (Last week, it was announced TikTok’s planned publishing house has folded.) And yet everyone knows the solution to electroshock the literary novel back to life: “just publish good books that people want to read.”

What does that mean? Well, that’s trickier. Maybe “writing books for the guy on the back of the bus”—as one novelist told me was his goal. You know, the “straight-forward tales with something to say, like Hemingway or Chekhov.” (Never mind that the guy on the bus seems pretty happy playing Candy Crush. In his soul, he surely yearns for realist short stories.) Or maybe it is “engaging novels written for the masses not just snobby elites, like Jane Austen!” (Never mind that Jane Austen’s readership in her lifetime was small and consisted largely of literal aristocrats.)

Mostly, “good books that people want to read” mean “the kind of books I personally like.” And yet the sheer number of books published each year—covering every style and genre possible—not to mention the even larger number of aspiring writers means some other dark force is at work. Maybe it’s snobby critics praising obscure novels that don’t resonate with regular readers? Or is it the pandering populists who heap praise on middlebrow slop that lowers everyone’s expectations? Perhaps it’s that high school English teacher who annoyed you? Or MFA programs or “woke” editors or conservative anti-intellectualism or TV or social media or the general spiritual decay of America caused by [insert another dozen things]?

Substack has been filled with such takes on the state of literature recently. Frankly, many feel like the literary version of “making up a guy to get mad at.” They’re rebuking a contemporary publishing landscape that exists only in their head. I’m going to ignore those and instead respond to an article I thought was informed and interesting… but rests on a couple unsupported claims.

The article I’m talking about is

’s piece “The Cultural Decline of Literary Fiction,” which has gone viral and filled my Substack Notes with restacked quotes. I get why. It’s an engaging read with many good points. Go read it. Overall, the article does a better job than most articles on this topic but I have some key disagreements. Here’s the summary of the argument provided near the top of the article:

The 21st century collapse in American literary fiction’s cultural impact, measured by commercial sales and the capacity to produce well-known great writers, stems less from identity politics or smartphones than from a combined supply shock (the shrinking magazine or academia pipeline) and demand shock (the move away from writing books that appeal to normal readers in order to seek prestige inside the world of lit-fiction)

I agree that “identity politics” has little to do with it—as the article notes, any decline surely starts decades before the “woke” (whatever that means anymore) era. And I think it is exactly right to emphasize the “supply shock” caused by the adjunctification of academia and collapse of well-paying newspaper / magazine jobs. I’m less convinced those shocks have dried up the well of aspiring authors so much as dried up the time authors have to dedicate to books. If you’re scrambling between adjunct gigs and low-paying freelance assignments without any security, it is harder to work on your Great American Novel. As I wrote a few months ago, literary authors’ bibliographies seem to be shrinking and that means less chances to have a breakout and become a well-known writer.

I do agree that the money in streaming TV / Hollywood has led some aspiring literary novelists to switch mediums. I’ve seen some of my peers do this. Although I think time, distractions, and economic instability are bigger factors. Put it this way: are there really not enough aspiring literary novelists in the age of proliferating online writing courses, expanding undergrad creative writing classes, and multiplying MFA programs? The supply has, if anything, increased.

Still, overall I think that side of Yingling’s argument is well argued. What is not sufficiently backed up, imho, is the other half: demand shock. The argument is two-fold. 1) literary fiction sales have steadily declined since the 70s to today when commercial prospects have been “killed off.” 2) The cause was a shift in awards and criticism to “postmodernism” in the 70s—and subsequent highly literary styles—which led to literary writers ceasing to publish books that appeal to readers.

It is obvious that the cultural status of literary fiction—and literature of all genres—has declined over the past 50+ years. Long gone are the days that either a Franzen or a King could become culturally ubiquitous. The same is sadly true of artists in almost all artforms outside of a few pop and movie stars. But neither of these two central claims seem correct to me.

As Yingling correctly notes, the only real data is BookScan and that doesn’t cover all sales and anyway was only founded in 2001 and so is useless for previous decades. The article’s evidence is mostly the yearly top 10 bestsellers as tracked by Publishers Weekly. The following epitomizing datapoint is repeated several times: “No work of literary fiction has been on Publisher’s Weekly’s yearly top ten best-selling list since 2001” (Franzen’s The Corrections).

This isn’t true.

Franzen himself appears again in 2010 with Freedom. I assume this was an honest oversight. But quite a few top 10 sellers were by authors who made their name in literary magazines, came out of MFA programs, and/or were published by literary imprints post-2001. 2002 and 2003: The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold (MFA grad / novel on Little Brown. 2005: The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova (MFA grad / novel on Little Brown). 2010: Freedom by Jonathan Franzen. 2015: Go Set a Watchmen by Harper Lee. 2015 and 2016: All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (MFA grad, novel on Scribner). 2020: Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng (MFA grad, novel on Penguin Press). 2021: The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (Orange Prize winner, novel on Ecco).

We could debate if they are all “literary fiction,” but certainly writers like Anthony Doerr (All the Light We Cannot See) and Celeste Ng (Little Fires Everywhere) were known in the literary fiction world and had published in notable literary magazines before their breakouts, both of which were on prestige literary imprints. All the Light We Cannot See would win the Pulitzer that year. And Franzen’s Freedom and Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchmen are certainly literary world books.

Now, I’m sure someone will comment that none of these books are as good as the greats of the 50s-70s. That’s fine. But the argument was that literary authors no longer write popular books. These were very, very popular books. The second rebuttal might be that books like Franzen’s Freedom was boosted by Oprah’s Book Club and Harper Lee’s book was a surprise sequel to a beloved classic, so both are historical aberrations more than anything else. But this is exactly the situation in the 80s and 90s.

The PW lists don’t demonstrate a steady decline of literary fiction. They show that by ~1980, commercial mass market fiction—mostly thrillers, romances, and war/historical page-turners—completely took over. When I look at the 1980s and 1990s list, only a handful of important literary works stand out. Namely, The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco (1983), The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie (1989), and Paradise by Toni Morrison (1998). There are a few others that could be called literary fiction, such as Cold Mountain or Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, but those don’t have terribly great reputations and in any event the total number is about the same or fewer than the last 20 years.

What about those big ones? Eco’s book was a global bestseller translated from Italian. Rushdie isn’t American either, and The Satanic Verses was famously a modest seller until he became a global news figure after a fatwa was placed on his head. Morrison only made this top 10 list after her historic Nobel Prize win. These speak to their unique circumstances more than they tell us anything about the popularity of American literary fiction writ large.

The top 10 list isn’t really that helpful. Half of it is self-help and kids picture books. If we widened this to top 100 adult fiction books each year, that might tell us something. Here you’d find many literary fiction bestsellers like On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, The Underground Railroad, A Little Life, James, every Sally Rooney book, etc. If there is data showing a notable decline in literary fiction sales decade over decade, I haven’t seen it. The data I’ve seen (of print sales via BookScan) shows that Literary Fiction is among the top selling categories in adult fiction. Not as big as the behemoths of Mystery/Thriller and Romance, but bigger than e.g. my beloved Science Fiction and Horror.

However. It does need to be said that Literary Fiction in official publishing categorization includes authors that many readers (myself included) would think of as, uh, let’s say “middlebrow.” The list of Literary Fiction bestsellers includes award-winning greats like Toni Morrison and George Saunders…but also Paulo Coelho and Delia Owens. This mirrors any genre really. The bestselling Science Fiction isn’t by authors like Gene Wolfe and Samuel Delany. It is franchise novels like Star Wars or movie tie-in releases for books like Ready Player One. Anyway, the fact remains that writers like Morrison, McCarthy, Whitehead, Franzen, Rooney, and so on do indeed sell a lot of books.

So, there is no evidence of decline of literary fiction in this data. Instead, there is evidence of the complete takeover of fiction by commercial fiction more or less starting in 1980. What happened? Can we blame it on Reagan’s election, like so many other things? Or do we…

Gather round young’uns and let me tell you about the olden days. When I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, the closest town had a couple (mostly used) bookstores. But bookstores weren’t where most books were sold. They were sold in the supermarket aisles, big box stores, and airports—thus the “airport novel.” You browsed novels while stocking up on apples and Advil. The largest stock of books in my town was at Sam’s Club sandwiched between the bulk jars of peanut butter and tables of three-pack t-shirts. You probably don’t need me to tell you that the kind of books stocked in these locations weren’t highbrow literary fiction, obscure postmodernist tomes, or lyrical short story collections. They were big fat commercial fiction novels with the authors’ names embossed in larger letters than the titles.

In my case, the nearby town was a college town so we had some good bookstores too. But in much of the country, it was commercial fiction sold at Walmart and the supermarket that moved units and thus took over the bestseller list. This was a large change in how books were distributed and sold, and also who they were sold to. Barnes & Noble expanded across the country in this environment. They had a wider selection, but devoted much of the space to the books their competition sold.

I don’t think you can understand shifts in literature without looking at these perhaps boring material questions of distribution, production, and labor conditions. They are boring but matter and often in surprising ways. For example, I once read a convincing argument that grocery stores led to the increase of page counts in commercial fiction books—think of how thick books by King and Rice became—because grocery store shoppers “buy in bulk.” If that sounds crazy, consider publishers put out many thin books and “novels” that would have barely been novellas in the past. Perhaps shrinking attention spans play a role here. But also, readers today shop online instead of physical stores and so are no longer comparing the physical sizes of different books before choosing which to buy.

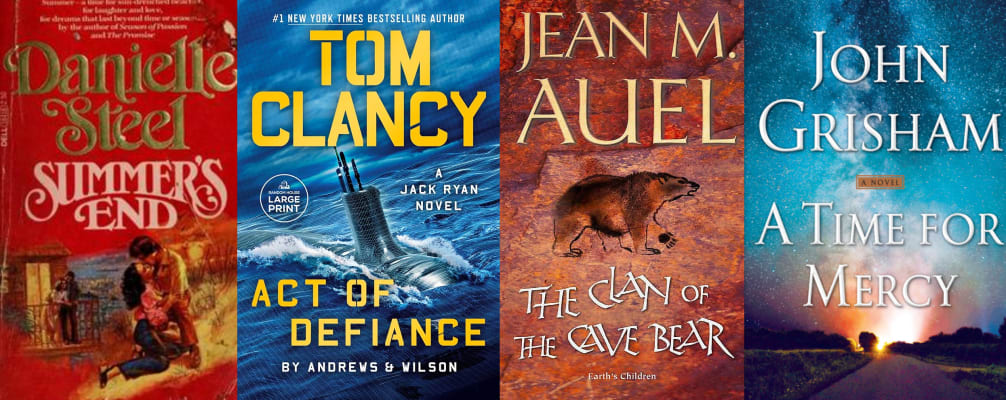

Anyway, the central point is that the rise of brand-name mass market commercial fiction is not necessarily the same thing as the decline of serious literary readership. Did the type of readers once buying Phillip Roth and Flannery O’Connor switch suddenly to Tom Clancy and Danielle Steel? Or are those simply different readers? For example, the type of readers who in a previous era bought pulp magazines instead of novels at all?

Obviously, I’m using grocery stores as a stand-in for a lot of different market changes that occurred between the 60s and the 80s. These market changes don’t tell the whole story, but I think it is less likely that literary fiction writers stopped writing popular work en masse than it is that corporate publishers learned how to market to the kinds of people who were never likely to read William Faulkner much less William Gaddis.

Maybe you find banal questions of distribution and market forces unsatisfying as an answer. Maybe you want to blame in on culture instead of capitalism. Certainly, culture shifts for many reasons. However you want to parcel out the blame, I think it is useful to use a wider lens. Ignore literary fiction for a second. The entire culture shifted around ‘74—as good a year as any to pick—to the era of mega pop stars, mega blockbusters, and mega airport novels. Mass market culture dominates almost every field.

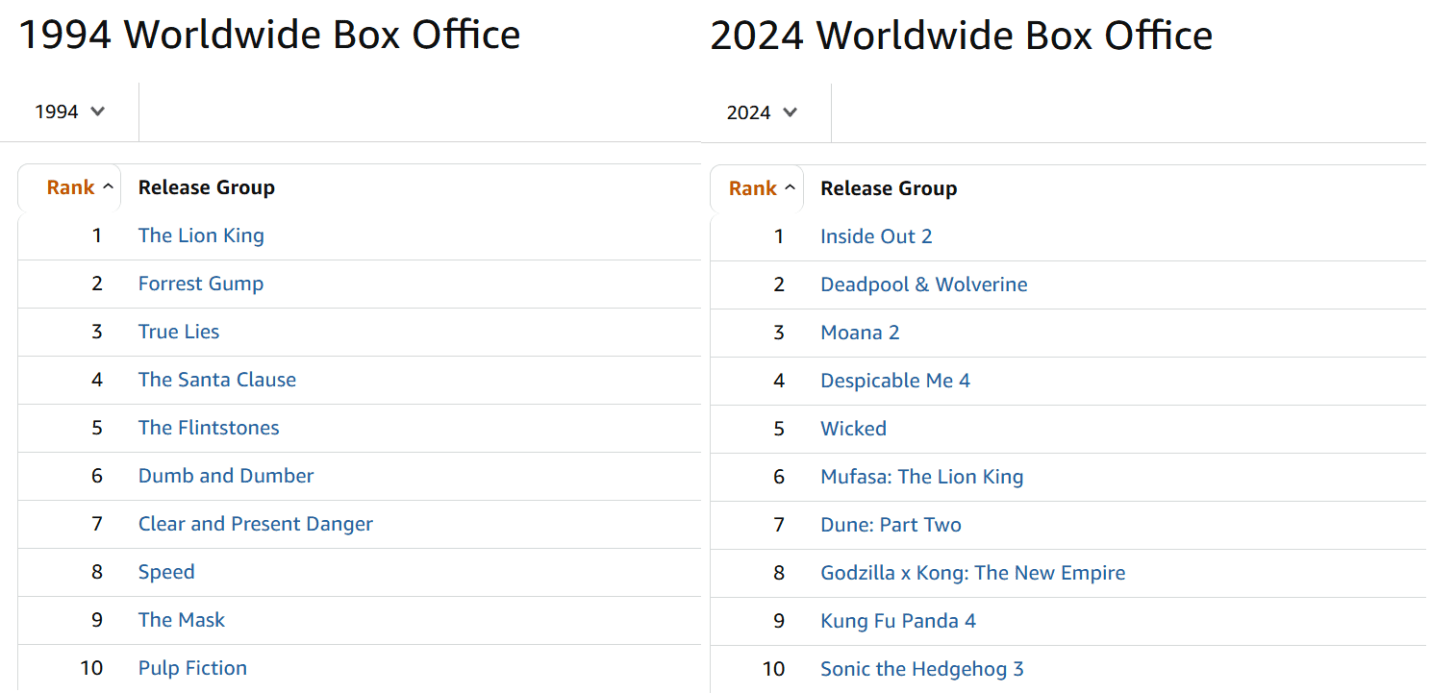

Just look at the shifts from 60s-70s to the 80s-90 and then to 00s-today at the top of the charts. The genre fiction bestsellers went from the likes of John le Carré, Agatha Christie, and Kurt Vonnegut to Clancy, King, and Steel and then to Patterson, Yarros, and Hoover. Surely as steep a decline as the literary bestsellers. The top box office films went from a variety of interesting movies in various genres like 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Godfather, The Exorcist, Blazing Saddles, and The French Connection (to pick but a handful of top box office films) to a box office dominated by big action blockbusters and children’s movies and then to our current franchise era where a handful of action and/or children’s IPs are given endless sequels, reboot, and “reimaginings.”

Ted Gioia recently noted that “Back in 2000, 80% of movie revenues came from original ideas. But this has now totally flip-flopped. Today 80% of the movie business is built on old ideas—remakes, and spin-offs, and various other brand extensions.” Gioia blames this on studio execs and says audiences are rebelling but… what evidence is there of that? 10/10 of last year’s top grossing films were sequels, reboots, or reimaginings. In this environment, a movie like Wicked—an adaptation of a hit broadway play adapted from a popular novel that reimagined a hit film that was adapted from a popular book—feels like a breath of fresh air just because it isn’t a sequel. (The sequel will be released later this year.)

I’m not saying that mass commercial art is all bad. Stephen King and Steven Spielberg, to pick two icons of the blockbuster era, are masters of their forms and have produced excellent work. And I’m certainly not saying that serious, innovative, and interesting art disappeared after 1980 by any means. But the great stuff flourished in the margins, in counter cultures, in independent scenes, and in the middle of midlists and mid-budget films. By 1980, mass market commercial art had taken over the top.

I think it is obvious that there’s nothing a few literary fiction authors could do to reverse the commercial takeover of books, film, and everything else. Still, even if brand-name thrillers and romances were going to dominate, perhaps a different sort of literary fiction could have performed better? Is it true that in the 70s awards and literary fiction as a whole eschewed popular tastes in favor of obscure postmodernism?

Amusingly, I typically hear the opposite argument in my circles. That critics and awards favor bland middlebrow works and readers looking for serious literary fiction get turned off by how disappointing the acclaimed books are and so turn to classics or other artforms entirely. But anyway let’s stipulate that in every artistic medium and field, awards diverge from merely popular tastes. This is true even in “popular genres” like science fiction, where there is little overlap between top SF sellers and Hugo / Nebula winners. It is true of the Oscars, where fans still complain the voters are “biased against Marvel movies” and the like. This has been true of “literary” prizes like the Pulitzer and National Book Award in every decade. The question is if there was a notable shift towards more obscure work staring in the mid-70s.

Here is how Yingling puts it: "Who else was winning awards at this time? With Gravity’s Rainbow’s National Book Award in 1974 (and refused Pulitzer) it was increasingly postmodern authors like Pynchon, Barth, and Gaddis, none of whom ever sold a meaningful number of books."

This is a version of an argument I’ve seen many times. But do the facts support the claims? Here are the authors the Pulitzer awarded between ‘74 and ‘89: Eudora Welty, Michael Shaara, Saul Bellow, James Alan McPherson, John Cheever, Norman Mailer, John Kennedy Toole, John Updike, Alice Walker, William Kennedy, Alison Lurie, Larry McMurtry, Peter Taylor, Toni Morrison, Anne Tyler. These sure seem like pretty standard literary realist and/or authors of historical works that appeal to broad audiences. More or less what was awarded in the previous decades.

(Gaddis, Pynchon, and Barth never appear as winners or finalists of the Pulitzer, other than the negated Pynchon ‘74 award.)

That National Book Award does go to Gaddis one year in the 70s and to DeLillo once in the 1980s. Score two for the postmodernists. Otherwise? Here are the 74-89 NBA winners: Robert Stone, Thomas Williams, Wallace Stegner, Mary Lee Settle, Tim O’Brien, William Styron, John Irving, Wright Morris, John Cheever, John Updike, William Maxwell, Alice Walker, Eudora Welty, Ellen Gilchrist, E.L. Doctorow, Larry Heinemann, Peter Dexter, John Casey.

Don’t these seem too instead of un- conventional? Irving’s The World According to Garp was a massive commercial hit. The Killer Angels is every Civil War buff uncle’s favorite novel. Tim O’Brien’s popular war stories are taught in high school classes. The handful of postmodernist wins are dwarfed by the number of Mailer / Updike / Doctorow type popular literary realists. Aren’t these exactly the sorts of books being advocated for?

What about more recent decades? A scroll through the last 20 years of Pulitzer Prize winners shows many breakout literary fiction bestsellers: The Road, The Goldfinch, All the Light We Cannot See, The Underground Railroad, James. Also note that these authors didn’t win such awards until they were popular. The National Book Award winners are a bit more aesthetically diverse, but they also include many bestsellers and have even more as finalists like Station Eleven and A Little Life. Most, though not all, of the books that appear are very readable books with sales potential even if they didn’t become bestsellers. Many have had TV/film adaptations. Very few are the dense tomes of confusing lyrical prose that people seem to imagine.

Put it this way, from 1974 to today, if you wanted to win a major literary award you have been far less likely to do so writing A) a dense tome of lyrical prose than B) the bestselling novel of the year that could plausibly be labeled “literary.”

Obviously, some authors in every era write challenging, innovative, and artistic—or if you prefer “boring, snobby, and pretentious”—books. There are always writers who prefer the tastes of critics to the masses, who don’t mind writing for a small audience, and who care about art more than sales. Thank god, I say. But, no matter your taste, let’s be real. Today, those writers—with only rare exceptions—get small advances without marketing support and/or publish on small non-profit presses. They sell their books to a limited audience who seeks out those types of books. Their books are unlikely to even be encountered by your average American or bestseller-buying reader.

Has there ever been a time in human history when people didn’t think the glory days were gone? That art was better, purer, and more popular in the olden days?

I’m now old enough to have watched this happen in real time. When I was in high school and college, authors like David Foster Wallace and Zadie Smith were considered pretentious “hysterical realist” blowhards. Jonathan Lethem, Jennifer Egan, and Michael Chabon were thought of as lightweights who “slummed it” in genre. Hell, Franzen himself was considered the epitome of pretentious literary garbage when he was topping bestseller lists. Several commercial fiction authors launched a whole campaign against Franzen—dubbed “Franzenfruede”—saying he was snobby nonsense “no one actually liked” who had been forced on unwitting readers by critics and Oprah.

Now, they’re the very authors held up as the last remnants of the lost literary fiction Eden!

When I was in high school, B.R. Myers popular A Reader’s Manifesto made a version of this “literary books stopped writing for the guy on the back of the bus” argument. Myers framed it as a “growing pretentiousness” among literary writers who focused on artsy prose instead of stories people want to read. One of Myers central targets was Cormac McCarthy, who was only a few years away from topping bestseller lists, chatting it up with Oprah, and becoming one of the most popular novelists in America. I highlight this goof because it’s a good example of how often predictions of what can or can’t be popular fail. A few years ago, if you asked for examples of contemporary “postmodernist” authors whose works would never find a mass audience, Percival Everett and Colson Whitehead might’ve topped the list. Then Whitehead’s magical realist Underground Railroad and Everett’s metafictional and intertextual James both became bestsellers.

No one knows what will be popular in the future, and we always rewrite the story of the past. It’s quite possible—nearly certain, even—than in a decade or two people will be lamenting the lost glory days when books like James and The Underground Railroad could top both awards and bestseller lists. Or when Eileen and Normal People could appeal to both literary readers and the general public.

Having said that…

While it is enjoyable to blame the decline of art on the kinds of art you don’t like—whether it’s “woke writers,” “obscure postmodernists,” or “pretentious stylists” or anything else that annoys us—the less satisfying reality is that most of this comes down to much larger issues that have no easy fix and are hardly limited to publishing. In publishing we lament the ability to break out debuts, and they also complain about this in the music industry. Writers decry the decline of the midlist just like filmmakers complain about the decline of the mid-budget film. The way that big tech companies have monopolized attention and flooded us with cheap or free “content” on attention-sucking apps affects every art form. Concentration of wealth in the top 1% of successful artists/franchises, the disappearance of livable income streams for “mid level” artists, the difficulties of discoverability in a fractured media environment… these issues cut across the culture.

Still, even if the biggest issues are ones that there are no easy fixes for—serious government regulation? Butlerian jihad against social media and smart phones? Just waiting for GenAI slop to destroy the internet itself?—I don’t want to cop out and say there are no problems in publishing in general and literary fiction in particular that could be fixed.

In my view, most of them revolve around an overfocus on bestsellers though. Publishers have become so reliant on a blockbuster or bust model, where one or two megasellers supports an entire imprint, that they throw stupid money at new trends. You can see this most clearly in the more commercial spaces where—these days—publishers are chasing the likely fleeting Romantasy craze in the same way they chased the fleeting dystopian YA craze of the 2010s: by throwing 7-figure deals at half-baked ideas. But even in literary fiction, publishers IMHO throw too much money at big bets instead of making smaller and smarter bets and then supporting those bets across a career. That’s most important to me, as a reader, because I want those books. In a world where academia and journalism are collapsing, authors need more support than ever if they are going to be able to keep writing books.

But, I also think this would be smarter for publishers’ bottom lines. Most authors historically break out, in terms of sales, later in their careers. Consider the most recent literary breakout bestseller: Percival Everett’s James. Everett is 68 and has been been cranking out genius books for literally decades, and he only got his due now. Many of the other bestselling literary authors I’ve named here were mid-career breakouts. Colson Whitehead became a bestseller with books 6 and 7 (Zone One and Underground Railroad). Cormac McCarthy with his 6th book (All the Pretty Horses). George Saunders had five story collections, two novellas, and one essay collection before his bestselling novel was published. Even Franzen and Morrison had a couple novels before their breakouts.

Publishers, and the literary world in general—from professional critics to literary Substackers—could do more to promote good books in the backlist. The literary world tends to drop books after publication, but if the current social media-driven era has taught us anything is that readers do not care about when a book was published. Song of Achilles hit the PW top 10 a decade after its publication because it went viral on BookTok. This Is How You Lose the Time War went viral several years after publication. You can’t engineer such viral success, but there are other ways publishers, critics, and so on could keep supporting books they believe in and promote backlists when front lists titles come out. And the reason those books went viral is that people who loved them passionately recommended them.

There are many other things I’d change about publishing. But also, literature isn’t publishing. What sells has little to do with what’s moves you. More great authors have died in obscurity than topped bestseller lists and the next great book that shakes you, expands you, and makes you see the world in a new way is unlikely to be found by checking BookScan stats. Good literature keeps being written regardless of trends, declarations of the novel's death, or the preferences of guys on their phones in the back of buses. Leave the sales worries to the big publishers’ accountants. It is far more important to write the unique, weird books that only you can write. And as readers, just seek out great books, read them, and share them with others who might love them too.

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

.png)