In June 1825 Samuel Pepys’ diary was published for the first time. It was an instant hit. Newspapers were soon full of reviews quoting memorable passages from this secret journal: Pepys’ descriptions of the Great Fire of London, his new wig, and his first ever ‘Cupp of Tee’ were among the favourites. Further editions followed, and by the end of the 19th century the diary was celebrated as a classic of British history and literature. Today, Pepys is the star of museum exhibits and historical novels. Excerpts from his diary are often used to introduce students to the Restoration period and, indeed, to introduce history: across England, six-year-olds following the National Curriculum can tell you about how Pepys buried his expensive cheese to protect it from the fire.

Since its publication Pepys’ diary has been admired as an unusually full and frank account of his times. Yet its fame has also been driven by what readers were not being allowed to see – by what Pepys or his editors might be hiding. That Pepys took steps to mask the contents of his diary has always been a selling point: secrecy attracts readers. In the 19th century substantial parts of the diary were judged too offensive to print. Much of it did not seem important enough to rise to the status of ‘history’, and so likewise remained unprinted. The early editions of Pepys’ diary were therefore extremely selective and heavily censored. It was not until the 1970s, following the Obscene Publications Act of 1959, that the full text was finally published.

Reputation management

Pepys kept his diary between 1660 and 1669, recording a host of miscellaneous information. The passing of parliamentary bills and his passing of ‘6 or 7 small and great farts’ were both worthy of record. There was much in the diary that Pepys needed to keep from others’ eyes because it could have destroyed his career as a naval administrator, his reputation, or his marriage. He logged his receipt of ‘gifts’ (or bribes) from his navy job. He recorded his seditious views about his superiors. Lady Castlemaine, the king’s chief mistress, ruled Charles, for example, because she had skills equal to those depicted in Italian erotic literature: she had ‘all the tricks of Aretin that are to be practised to give pleasure, in which [the King] is too able, having a large ––––’. The long dash is Pepys’, who in this case was being uncharacteristically decorous. Among the passages that he really wanted to keep secret were those about his sex life. A few of his sexual encounters were mutually enjoyed; many others involved exploitation or violence, such as his molestation of his young servant Susan or his assaults on the tavern maid Frances Udall. Any of them would have incensed his wife, Elizabeth, had she been able to read the diary.

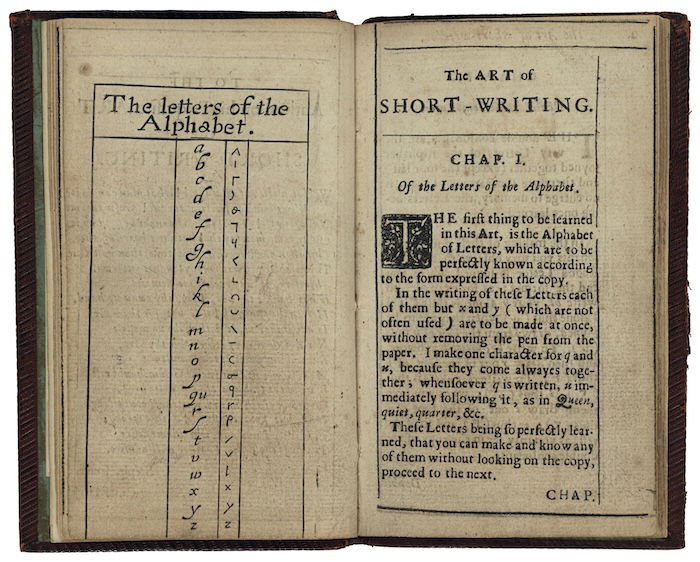

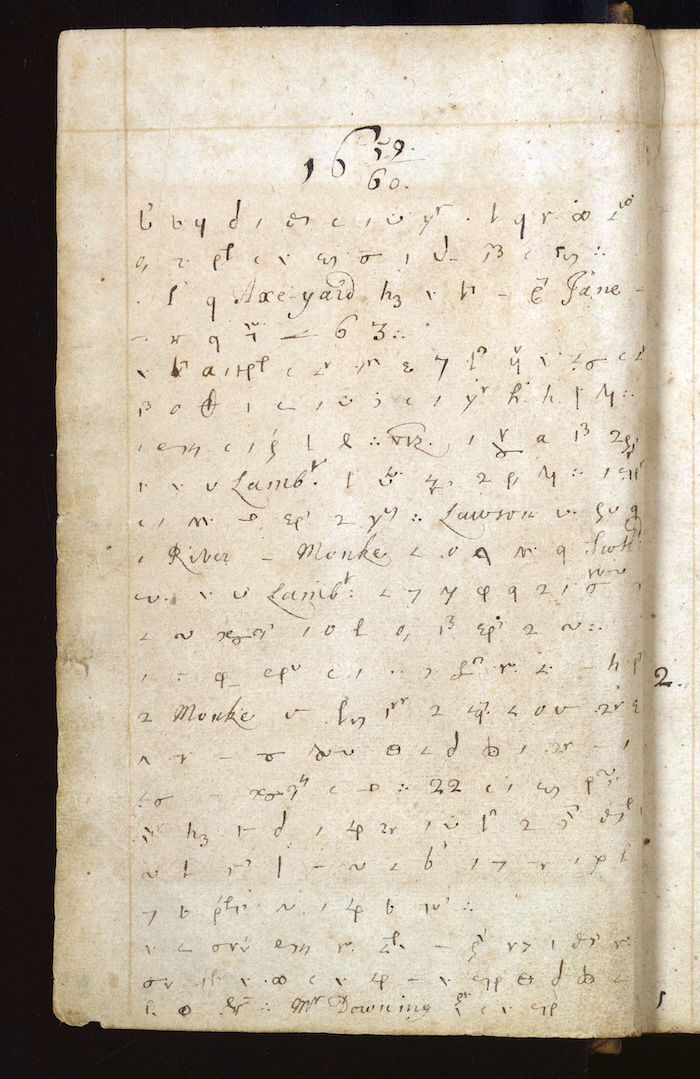

So, Pepys took precautions. He wrote in shorthand to prevent his diary being easily read. These symbols were not a code: Pepys used Thomas Shelton’s Tachygraphy, a shorthand system first published in the 1620s and available in many editions across the century. He gradually adopted extra measures for protecting some diary passages. In early 1664 he started recording some of his sex life in French (still using shorthand); in 1666 he added other languages such as Spanish, Latin, and Greek to the mix; and in 1667 he began to add extra symbols to his shorthand to further cipher some sexual encounters. In 1668, for example, Pepys worried that he had angered the actress Elizabeth Knepp by ‘ponendo her mano upolon mini cosa’. A would-be reader would need to know the shorthand, identify and translate the Latin and Spanish, and remove the extraneous symbols to reveal that Pepys had been ‘putting her hand upon my thing’.

Page from Tachygraphy, by Thomas Shelton, 1674. Folger Shakespeare Library. Public Domain.

Page from Tachygraphy, by Thomas Shelton, 1674. Folger Shakespeare Library. Public Domain.

Although Pepys sought to ward off readers in the 1660s, by the time he wrote his will in 1703 he had changed his mind. The six volumes of his diary deserved to survive him and be read. He left them as part of his carefully selected library to Magdalene College in Cambridge, his former college to which he had previously made donations. Among the other books he bequeathed were Shelton’s manuals on tachygraphy. The diary therefore travelled with the means to read it. Pepys’ bequest came with strict instructions on its preservation. The ‘Bibliotheca Pepysiana’ (the Pepys Library) was to be under the control of the college’s master. It was to be kept intact and unchanged ‘for the benefitt of Posterity’.

The conditions under which Pepys left his library were designed to preserve it, but also to shape who could access its most sensitive contents. Any man who succeeded in reading Pepys’ diary would have passed multiple hurdles – gaining access to the library room, identifying the shorthand, and taking the trouble to read it. Such a scholar was not likely to be predisposed to judge him harshly. Any master of the college was unlikely to allow material from the diary to be published if it would destroy the reputation of a generous benefactor. Pepys was throwing the dice on leaving posterity to judge him through his diary, but he had weighted those dice.

‘Objectionable’

The dice took a long time to fall. After all, why bother ploughing through the six-volume diary of a largely forgotten 17th-century official? Especially if it meant battling with an antiquated shorthand that was now unidentified? It was not until the turn of the 19th century that efforts were made to read the diary, and not until 1818 that work got underway on transcribing the whole text. In that year, the master of Magdalene, George Neville, recruited his aristocratic uncle to take a look at the manuscript. The Memoirs of Pepys’ friend John Evelyn had just been published, which had piqued their interest in Pepys’ account. Together they concluded that the shorthand would be crackable, although neither of them fancied the task. Neville therefore took the time-honoured route for dealing with tedious academic work: he hired a student to do it. John Smith, an undergraduate at St John’s College, became the first person other than Samuel Pepys to read the entire diary.

The opening of Samuel Pepys’ diary, 1660. By permission of the Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge.

The opening of Samuel Pepys’ diary, 1660. By permission of the Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge.

The standard account of John Smith’s role has him working for three years on the transcript, gradually identifying the diary’s symbols while sadly unaware that there were manuals available nearby. Smith later described himself as the diary’s ‘decipherer’, a man who had no substantial help from others, and who had endured ‘arduous labours’. This was the truth, but only part of it. From Smith’s transcript it is clear that very early on he had, in fact, identified that the shorthand was Shelton’s and had laid his hands on a manual – as Pepys had almost certainly intended. Having done so, Smith kept that knowledge quiet.

Now familiar with Pepys’ shorthand, Smith tackled the additional protections used for some sexual passages. At first, he chose not to transcribe these sections, replacing them instead with the word ‘Objectionable’. As he progressed, Smith gave up his censorship – probably because the objectionable passages were taking up more and more of Pepys’ days. The upshot of his initial caution, however, meant that even the men in possession of the new transcript of the diary never had a full version. Despite the diary’s growing fame, Smith would remain the only person to have read the whole until further editorial work was done in the 1870s.

A cheat and a liar

For much of the century, the man who determined what the public saw of the diary was Richard, 3rd Baron Braybrooke. Braybrooke edited its first edition and went on to oversee all the major editions before 1875. It was he who ultimately selected what would be printed from Smith’s transcript. Pepys’ description of the Great Fire immediately struck him as important. ‘This is very curious’, he wrote excitedly, next to Pepys’ account of how he had rushed to Whitehall and ‘did tell the King and the Duke of York what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing could stop the fire’. Unfortunately, not all the diary rose to this level of historical significance. For the most part, Pepys’ accounts of everyday life were not of historical interest – they seemed prolix and trivial. Worse, he was prone to recording episodes that undermined his authority and credibility: his language was uncouth; he admitted lying; he took bribes; and he repeatedly betrayed his wife. The simplest way to deal with such unhistorical or damaging passages was to cut them. This protected readers from Pepys’ offensiveness, while protecting Pepys’ reputation (and the reputation of Magdalene) from readers’ judgement.

Elizabeth Pepys, engraving by James Thomson, 1828, after the 1666 painting by John Hayls.

Elizabeth Pepys, engraving by James Thomson, 1828, after the 1666 painting by John Hayls.

When it finally appeared in 1825 the first edition contained about a quarter of Pepys’ diary. Braybrooke explained to readers that since Pepys ‘was in the habit of recording the most trifling occurrences of his life’, it had been necessary to greatly curtail the manuscript. He had, he said, sought to retain everything that might be ‘of public interest’, along with topics to illustrate ‘the manners and habits of the age’. Court scandal counted as ‘public interest’, so a cleaned-up narrative of Lady Castlemaine’s affair with the king made it into print (the details of the king’s anatomy, of course, did not). Overall, the main casualty of Braybrooke’s editing was material that we would now identify as ‘social history’. This was then a new term, first recorded in 1814. Pepys’ accounts of ordinary Londoners, public opinion, and his private life were all drastically reduced. References to women and lower-status men were particularly liable to be cut. Jane Birch, for example, was Samuel and Elizabeth’s favourite servant. She features frequently in the diary manuscript: negotiating over her wages; mocking the neighbours; assisting her family; ‘cutting off a carpenters long Mustacho’ in revenge for some unspecified slight; repulsing Pepys’ efforts to ‘tocar’ (touch) her breasts before ‘giv[ing] way to more then usual’; and, eventually, marrying a fellow servant and leaving the household. In Braybrooke’s edition she is barely mentioned at all. Throughout this text, Elizabeth Pepys was also a much smaller presence than in the manuscript. Notably, her husband had no illicit contact with other women. Many of these women and girls, in fact, disappeared entirely from Braybrooke’s edition.

The whole truth?

The first edition lacked much of the content for which the diary is now valued, but it proved a great success. Readers generally found Pepys’ miscellaneous record to be ‘curious’ and ‘amusing’. This book offered much more on manners, customs, and socialising than other Restoration sources. In his review Walter Scott described it as a ‘mine’ of treasures for readers with historical interests ranging from crime to theatre. However, whether the diary had ‘historical importance’ was debated, for Pepys’ narrative did not seem to transform understandings of the 1660s. Frances Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review was ‘rather disappointed’ by the diary’s ‘political or historical parts’ – Pepys’ discussion of high politics and national events. However, he argued, accounts like this that revealed the ‘manners and habits of former times’ were ‘indispensable’. One needed to know such details to understand ‘middle life’ and the ‘central masses’ of the people – without this there could be no ‘true’ picture of the past. The diary was spurring discussion about whose lives counted as ‘history’.

Amid the excitement around the diary, Braybrooke’s substantial cuts rapidly attracted comment. They raised questions about the publication’s reliability and about acceptable levels of censorship. Reflecting on the diary, Scott argued that an edition intended for historians should really be a ‘literal transcript’ of the whole source, even in circumstances where ‘delicacy and decency’ demanded otherwise. For if a document was incomplete, how could a historian be confident in his judgements of it and its author? Less high-mindedly, readers simply wanted more of Pepys’ entertaining narrative. Rumours started to fly about what remained unprinted. The diary’s publisher, Henry Colburn, hinted that some of the ‘suppressed’ episodes concerned Pepys’ own misdeeds (an idea nowhere raised by Braybrooke). Readers wondered what might have been cut and, also, what Pepys himself might have concealed. In the Edinburgh Review, for example, Jeffrey pointed readers to the fact that Pepys’ fondness for his maid Mary Mercer seemed ‘a little suspicious’. He suspected that here Pepys had ‘not intrusted the whole truth’ to his diary. In fact, Braybrooke had cut Pepys’ sexual encounters with Mercer.

Speculation about what readers were not being allowed to see grew over the decades. In 1841 Leigh Hunt, writing in the Edinburgh Review, recalled how, following the first edition, ‘the suppressed passages were naturally talked about in bookselling and editorial quarters and now and then a story transpired’. He had heard of one passage which ended with the diarist comically begging ‘the pardon of “God and Mrs Pepys”’. This seems to have been a garbled version of an entry not included in the published text. In 1668 Pepys had begun a sexual relationship with his wife’s waiting woman, 17-year-old Deb Willet – a relationship which, unlike all his others, was eventually discovered by his wife when she walked in on Pepys ‘imbracing the girl with my hand sub su coats [under her skirts] and endeed I was with my main in her cony [hand in her cunny]’. Elizabeth sacked Deb and suffered months of jealousy and rage. Following one day of anger, Pepys did ‘by the grace of God, promise never to offend her more’ and prayed for God’s mercy. This was the leaked episode that had reached Hunt.

Plot holes

Calls for more diary eventually led to an expanded edition. Edited by Braybrooke, it came out in instalments between 1848 and 1849 and contained about 40 per cent of the manuscript. This was even more warmly received than the first edition, at least in terms of praise for the diary itself (reviewers were less enthusiastic about the editing). The Athenaeum called it ‘the best book of its kind in the English language … all other diarists are dull and heavy by comparison’. This new edition seemed to bring readers closer to Pepys, for ‘the writer is seen in a clearer light, and the reader is taken into his inmost soul’. It magnified the sense of Pepys as an unusually frank and detailed writer. Yet, this text also added to the perception of him as a frivolous, flawed figure who deserved to be laughed at for his eccentric prose and his peccadillos (particularly avarice, vanity, and his eye for women). As the satirists of Punch put it, Pepys’ ‘historical facts are highly valuable, the comments mostly sensible, the style is very odd, and the autobiography extremely ludicrous’.

While the new edition aimed to satisfy demands for more of Pepys’ private life, it caused as many problems as it solved. Braybrooke included more about Pepys’ family, servants, neighbours, and daily life, while still cutting material he deemed at all improper (such as Pepys’ extramarital relationships). The edition therefore presented readers with exciting new narratives, but also glaring plot holes. One new episode quickly became notorious. On 12 January 1669 Elizabeth appeared at her husband’s bedside with ‘tongs red hot at the ends, [and] made as if she did design to pinch me with them’. What could have prompted her to do this? There was little to go on in Braybrooke’s text. The real answer was that Elizabeth, having recently discovered her husband’s relationship with Deb Willet, believed he had been meeting with her that day. However, since Braybrooke’s Pepys had no affair with Deb, the bizarre passage remained a mystery. In late 1849 it was well known enough simply to be referred to by one newspaper as ‘the tongs adventure’.

‘The Wife’s Portrait’, engraving after the 1852 painting by Alfred Elmore. Public Domain.

‘The Wife’s Portrait’, engraving after the 1852 painting by Alfred Elmore. Public Domain.

The expanded edition sparked creative responses, fuelling the diary’s reputation for secrecy, scandal, and entertainment. A dominant theme in these reactions was to imagine what Pepys and his editor had left out. One such response was Alfred Elmore’s painting, The Wife’s Portrait, which was shown at the Royal Academy in 1852. Elmore depicted a day in 1666 when Pepys, Mrs Knepp, and Mary Mercer accompanied Elizabeth to an artist’s studio to have her portrait painted: ‘While he painted, Knipp, and Mercer, and I sang.’ In Pepys’ account this seemed a delightful experience for everyone. Elmore’s painting prompted viewers to question this. The Examiner saw the painting as a moment of discomfort for Elizabeth, but one in keeping with a comic view of the diary: ‘Buxom Mrs Pepys’ dared not break her pose enough to ‘look round at her husband as he throws himself into the delights of music with his lady friends’. The Illustrated London News viewed the scene differently: Elizabeth showed ‘sadness’ at ‘the neglect to which she is habitually subject’.

The impact of the 1848 diary was the greater because it was published in instalments, which, like a serially published Victorian novel, built up excitement about what might be revealed. In autumn 1849, as publication ended, the New Monthly Magazine noted many readers would be ‘sorely grieved’ that there would be no continuation of Pepys’ ‘most amusing work’. Fortunately, the Monthly had a solution for readers in search of more Pepys: fan fiction.

The magazine offered a short story, Dudley Costello’s ‘An Evening with Knipp’. In it, Pepys and Mrs Knepp escape for an evening of merrymaking around London, pursued by their enraged spouses. Finally, Elizabeth catches up to the pair and drags her husband home. That night she appears at his bedside with ‘a weapon as formidable as if it had been prepared by the Devil himself – nothing less than a pair of tongs, red hot at the tips!’ Thus readers were given an explanation for ‘the tongs adventure’. This was an approach to diary reading which thrived on censorship and on questioning the reliability of Pepys’ own perspective.

Secret history

Pepys’ plan to leave his diary to benefit posterity had worked out astonishingly well – even if he had not emerged with a glowing reputation. By the mid-19th century Pepys had become widely celebrated: his diary was recognised as historically important and his evocative descriptions were much quoted. Yet the extent of his diary’s contents remained known only to the few of Neville’s family who had access to the (incomplete) transcript.

For decades by this point, readers had been agitating for more diary to be published, to further historical knowledge and to further their entertainment. Editorial censorship had spurred rumours and jokes. As a result, Pepys’ diary had a reputation for scandal out of proportion with what the published texts contained, although considerably less than what Pepys had written. In 1876 the Athenaeum wryly summed up the situation by remarking that Braybrooke had cut ‘much that was too naughty to be printed’ and, word having got out, ‘everyone curious in social history has looked into every new edition with a hope of meeting with at least some traits of that naughtiness’. Over the decades, ‘social history’ and the fame of Pepys’ diary had increased together, feeding each other. Today, Pepys’ reputation for ‘naughtiness’ remains powerful, for good and ill. The promise of mischievous, entertaining, unconventional history draws readers to the diary. Yet, even with the full text available, the expectation of ‘naughtiness’ can make it more difficult for readers to see when Pepys’ ‘amours’, to use his language, would more accurately be described as assaults. After two centuries, the reputation of Samuel Pepys continues to be inextricably linked to secret, social, and ‘naughty’ history.

Kate Loveman is Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture at the University of Leicester and the author of The Strange History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary (Cambridge University Press, 2025).

.png)