Context: this essay continues previous explorations of themes related to de-industrialisation and the like. It introduces the notion of a financial psychosis as a key component of the present economic, social and cultural malaise that underpins the piturbutations of American politics. My contention here is that America actually still makes things, but the things it makes no longer carry the same symbolic and mythological authorities of the things of everyday life. Financial psychosis re-emerges in a companion essay that looks at the turn to so-called stablecoins, crypto-memes and the establishment of an American national cryptocurrency strategic reserve.

It has become commonplace to lament that “America doesn’t make things anymore.” Politicians, commentators, analysts and indeed, working people alike, reach for this refrain to explain the unraveling of the social fabric, the decline of working-class wages and the erosion of national confidence.

There were better times, as the politics of nostalgia yank at the heartstrings and the mnemonic reflex takes us back to the days of Taylor’s scientific revolution in production line management and imagines a hagiography of hard factory work. Yet, as Trump introduced tariffs and spoke wistfully of the return to a “golden age”, Chinese social media memes mocked the nostalgia invested in these tropes with images of Americans again suffering the toil of factory work. To add insult to injury the imagery was ‘made’ with AI.

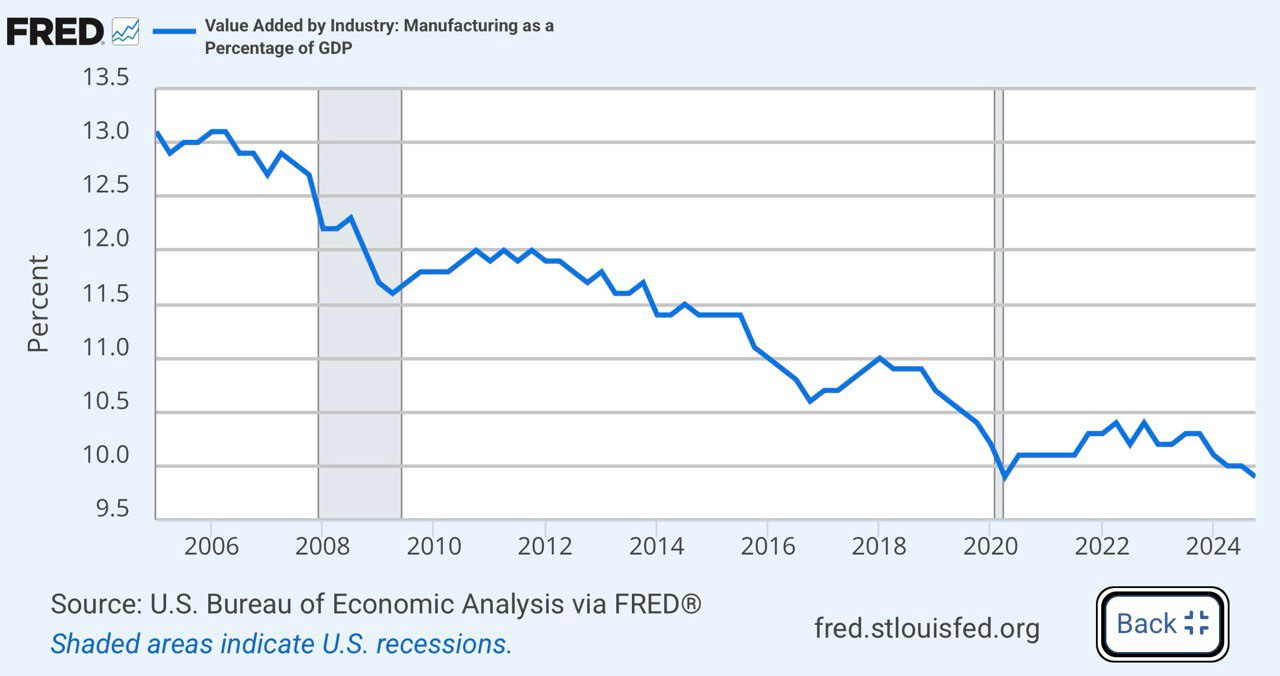

Some American analysts don’t lament the loss of “low value” manufacturing. They speak of the services economy as materially and symbolically representative of progress. For them, there is little admirable about the daily drudge of factory toil as they celebrate the progress of America. That manufacturing employment as a percentage of GDP fell persistently between 1960 and 2010, before levelling off this past decade or so, speaks of progress rather than regression.

When it comes to numbers, we are at the intersection of two narrative frames; one that focuses on proportions, the other on absolutes.

The statement that “America doesn’t make things anymore” is in a literal sense untrue. The United States remains one of the world’s largest manufacturing economies, responsible for roughly 12–14% of global value-added output in financial measure terms. This makes the U.S. the world’s second largest manufacturer. It continues to produce high-value machinery, aircraft, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and defence equipment.

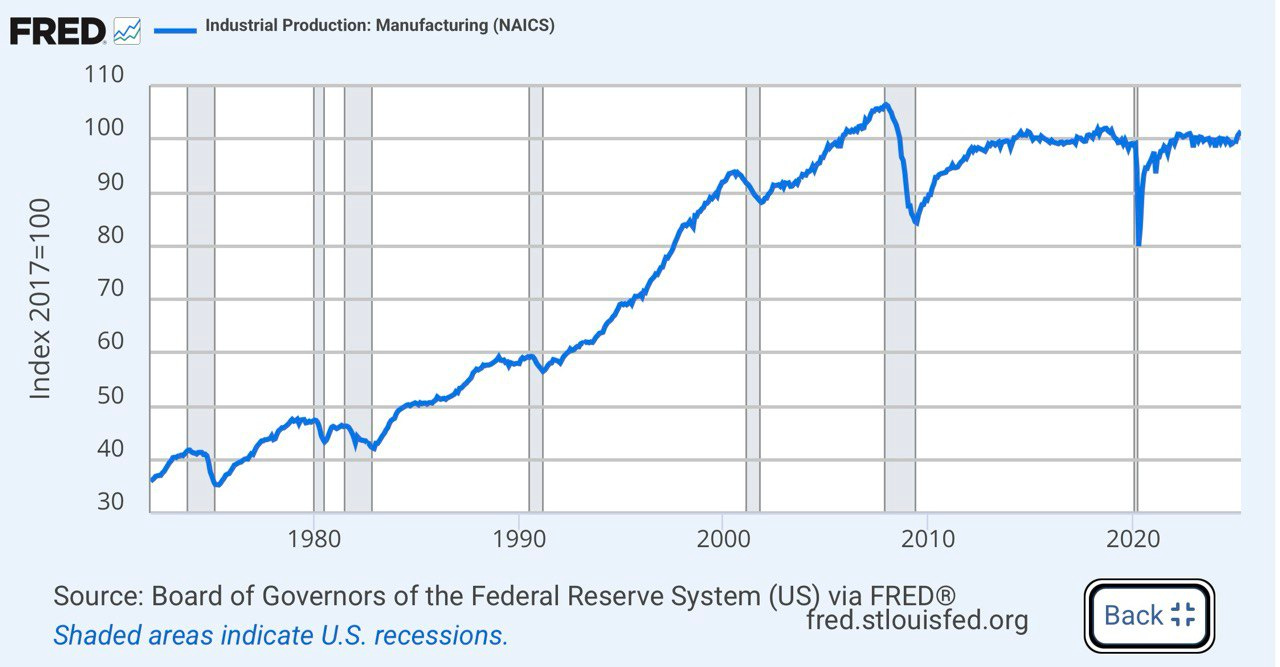

In quantitative terms, America still manufactures. Indeed, American manufacturing output in absolute terms is many times higher today than it was five decades ago. The evidence on this front is actually very clear. Output levels peaked before the GFC (2008) declined, recovered and have more or less plateaued. See Figure 1.

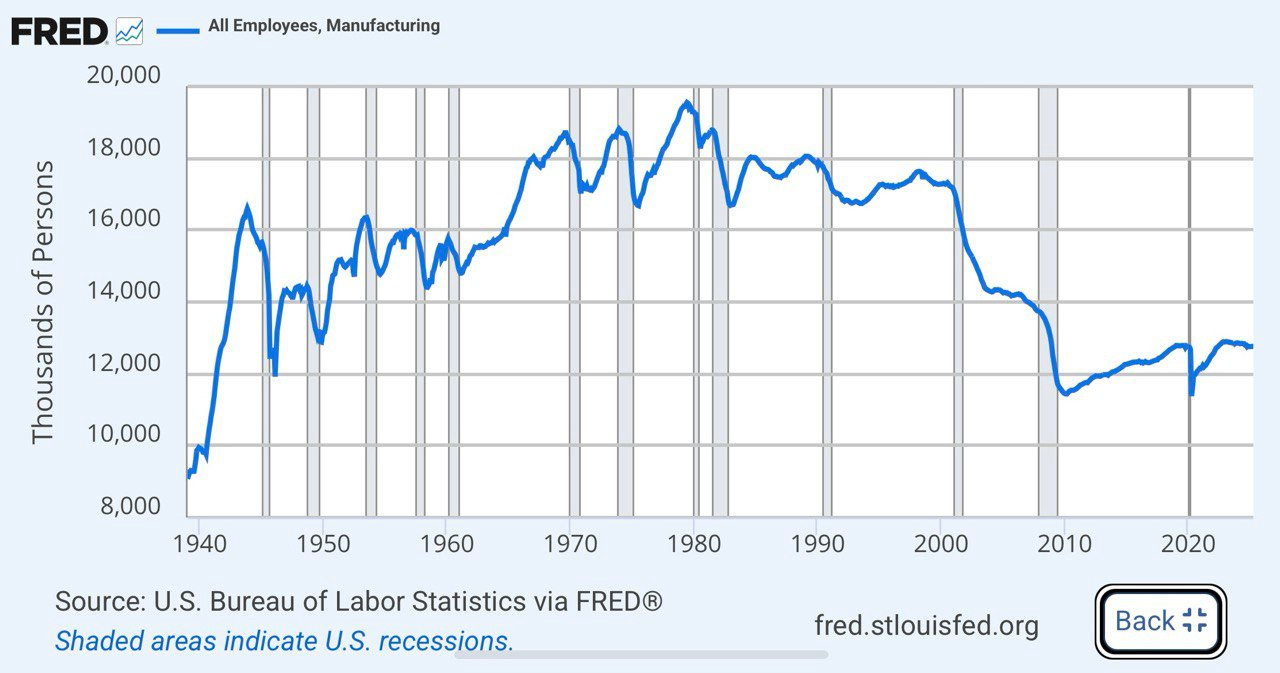

Manufacturing employment today is certainly less than it was in the 1970s and 1980s - the peak - but in absolute terms it’s back to levels last seen in the 1950s. See Figure 2. Proportionately, however, in both output and employment terms manufacturing’s contribution overall is a diminished shadow of its formal near-colossal status. This parallels the decline in output as a percentage of GDP. This is clear in Figure 3.

But the crisis is not a crisis of numbers per se. It is, rather, a crisis of meaning; a rupture not in the ledger, but in the cultural imagination. If America still makes certain kinds of things, it no longer feels like it does. The sensibility once built around the factory - the sense of shared identity, productive pride and visible contribution to a collective life - has withered. What has disappeared is not entirely manufacturing itself, but the mythology that once surrounded it.

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes argued that myth is not a falsehood, but a second-order semiotic system. Myth is a cultural device that transforms history into nature, rendering human-made structures as inevitable and eternal. Myths are a necessary part of the human and social condition.

The postwar American industrial economy was, in this sense, mythic. The factory stood not merely as a site of production, but as a symbol of dignity, progress and national coherence. The “Made in America” label evoked more than origin. It conferred moral value. The tools of industry - steel, rubber, engines, the whirr of the assembly line - were not neutral or abstract artefacts. They were signifiers in a system of meaning that tied personal and community identity to national purpose.

The things that America made functioned as social, cultural and symbolic totems that pulled people together in a sense of collective identity and mission. Even efforts to resuscitate Boeing founder on the much scrutinised safety and performance record of what was once a flagship to American engineering prowess.

That myth no longer holds. Even as industrial output remains high, in dollar terms, its presence in everyday life has diminished to the point of near-invisibility. The goods that surround most Americans, their clothes, their shoes, their phones, their appliances, their back-to-school supplies and their furniture, are overwhelmingly made elsewhere. The tangible proximity between citizen and production has dissolved. What remains are fragments, ephemera separated in space and time: distant supply chains, unmanned factories and disembedded capital-intensive production facilities that yield little in the way of employment, and even less in shared symbolic resonance.

The result is a condition best described as hollowing out, not merely the thinning of industrial employment or the closure of plants, but a more fundamental loss of symbolic density. Barthes’ mythologies relied on visibility, on repetition and on signs woven into the fabric of daily life. Today’s manufacturing economy, though still present, does not register in that way. It is abstract, remote, and largely silent in the sensory world of most people.

Likewise, De Certeau, in his The Practice of Everyday Life, suggests that everyday practices are not just habitual, they are meaningful. When American workers once built cars, appliances or tools, their daily routines were deeply intertwined with production, skill and local purpose. The factory was not just a site of labour; it was also a symbol of social cohesion, identity and contribution.

But as production shifted overseas, these sites and symbols disappeared. Now, when Americans engage with objects in daily life - phones, clothes, shoes, furniture - they are often alienated from the processes that made them. The objects are imported, and so is the labour that went into them.

Even in sectors where production continues - automotives, for instance - the link between object and identity has frayed. Vehicle output in the U.S. has plateaued at ~10 million units per year for over a decade - the second most of any country, incidentally. But the factories producing them are smaller, more automated and less symbolically central than the industrial hubs of the mid-20th century. The car is no longer a totem of national production. Its origin is unclear, its brand associations fragmented, its workers increasingly invisible. One can drive an American-made car without ever encountering the idea of American manufacturing.

In contrast, the sectors that dominate current U.S. manufacturing - semiconductors, aerospace, pharmaceuticals - are largely removed from public life. They produce economically vital goods, but not goods around which shared social meaning coheres. There is no myth in a microchip, no affective surplus in a drone and no patriotic charge in an MRI machine. These are objects of function, not identification. They sit at the heights of value production, but at the periphery of cultural life.

De Certeau emphasised how consumers “poach” meaning from dominant systems. But in a world where consumption is severed from production, the autonomy of the consumer becomes illusionary. You can no longer make, fix, or even fully understand the objects that saturate your everyday life.

Hence, the prevailing disorientation. It is not simply that jobs have vanished - though many have. It is that the emotional architecture built around those jobs has collapsed. The factory, once a foundation for identity and collective belonging, now appears as either a ruin or a high-tech fortress; they are closed to the public, sealed off from the everyday. The human meaning of work has decoupled from the sites where productive activity still occurs.

Attempts to resurrect industrial significance through tariffs, reshoring, or “Buy American” campaigns serve as gestures toward a past that no longer exists. They seek to recapture a myth that has lost its material anchors. But myths cannot be reanimated by policy edict or rhetorical flourish. Barthes reminds us that myth depends on a system of signs, on the embedding of symbols in life. Without this embeddedness, appeals to industrial revival become aesthetic exercises, ornaments placed atop a structure that no longer holds the same place in the collective psyche.

The nostalgia that animates much of the current industrial discourse thus mis-recognises the nature of what has been lost. It is not simply the factory job, or even the wage, that people mourn. It is the disappearance of a framework in which labour, place, and identity once cohered. It is the silence that now surrounds production - its retreat from public life into cleanrooms, supply chains, and the anonymous logics of capital accumulation.

Even Trump’s paraphernalia reminds Americans of today’s realities.

This is not to say that new myths will not emerge. They may, in time, crystallise around new technologies, new forms of work or new symbolic systems. But they will not be recoveries of the old. Myths, as Barthes understood them, reflect the historical structure of feeling particular to a time and place. They do not survive their conditions. The myth of American manufacturing belonged to a moment of mass production, national industrial policy and Fordist social compromise. That moment has passed.

The closure of American factories turns the everyday into a disenchanted terrain, where people no longer “make do” with what they produce, but with what they are given - often from faraway places, through systems they cannot see or shape. This strips everyday life of its groundedness, its symbolic richness and its capacity for quiet resistance.

What remains is a vacuum - a period in which production continues but no longer speaks. The outputs still exist, but their cultural inscriptions do not. They are not symbols, but mere commodities. The society that once looked to the factory for its sense of self must now look elsewhere, or not at all. In the meantime, the hollowing out persists, not simply as economic fact, but as semiotic absence.

This absence cannot be resolved by imagining what once was, nor by projecting fantasies of return. This is the dead-end folly of the politics of nostalgia. It can only be lived through, reckoned with, and, perhaps eventually, transcended. But that transcendence will not take the form of a revival. It will require a recognition that the past is past, and that the myths that once made sense of it no longer hold explanatory or consoling power. The silence of manufacturing today is not simply about production in and of itself. It is about the end of a story that once gave production meaning.

In this way, the American manufacturing story continues, not as a tale of resurgence, but as a case study in mythological exhaustion. Its ruins are visible in more than shuttered plants or declining union rolls. They are visible in the cultural stillness that now surrounds work itself: a silence where once there was a chorus of meaning, pride and shared purpose.

In this context, the myth of manufacturing was not merely economic. It was metaphysical. It tethered people to the world through the tangible, through work that manifested in things that endured, and which mattered. Its disappearance is not just about globalisation or automation or trade. It is about a collapse in the symbolic structure through which people once made sense of their lives.

Yet this symbolic vacuum has not remained unoccupied. In the absence of embedded material myths, a new mythology has taken hold, one that is abstract, weightless and totalising. It is the fetish of money, an inversion of meaning in which value no longer arises from work or use, but from motion alone. Wall Street does not produce objects; it produces signs of signs, numbers whose only referent is other numbers. In this world, the aura does not reside in the object, but in the price. Reality is displaced by valuation.

The result is a form of financial psychosis, a collective delusion in which the measurable overtakes the meaningful. It is not simply that finance has grown; it is that it has stepped into the metaphysical breach once occupied by the factory, the workshop and the forge. The Bloomberg terminal becomes the sacred object, the index the new scripture. Corporate earnings calls carry more narrative power than any artefact on the shop floor. In place of aura, we have volatility. In place of thingness, we have a craving for liquidity.

This is not capitalism returning to its roots. It is capitalism unmoored from material referents - accumulation without anchoring, profit without production, wealth without world. The metaphysical longing once satisfied by the made thing now finds expression in the infinite deferral of satisfaction through speculation, arbitrage and the burdens of debt. Where once people lived among things that bore traces of time and touch, where texture mattered, they now inhabit a landscape of featureless surfaces: screens, metrics and disappearing promises.

And so, the American manufacturing story continues, not only as a story of material transformation, but as a site of ontological diminishment. What we are witnessing is not simply deindustrialisation, but a loosening of the world itself - its loss of depth, weight and resonance. The things remain, but they no longer speak. In their silence, the noise of finance becomes deafening - a substitute mythology whose power lies in its ability to mesmerise, not to ground. It offers the frisson of motion in place of meaning, ledgerised quantity in place of quality and abstraction in place of presence.

To describe this condition is not to lament what might have been, nor is it to prescribe what should be. It is to observe, with a clear eye, the exhaustion of a symbolic order and the ascent of another. It speaks of a shift from a world of work and things to a world of signs and simulations. And in that shift, the everyday is emptied of its former sacredness, leaving behind not a crisis, but a quiet metaphysical malaise: a society rich in fictitious output but poor in substantive meaning.

.png)