When Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification,” a useful, new word for the way online platforms decay, or decline into unusability, he not only gave us the word of the year, at least according to the American Dialect Society and, later, the Australian Macquarie Dictionary. He gave us validation.

“It’s not just you,” Doctorow said. “The internet sucks now.”

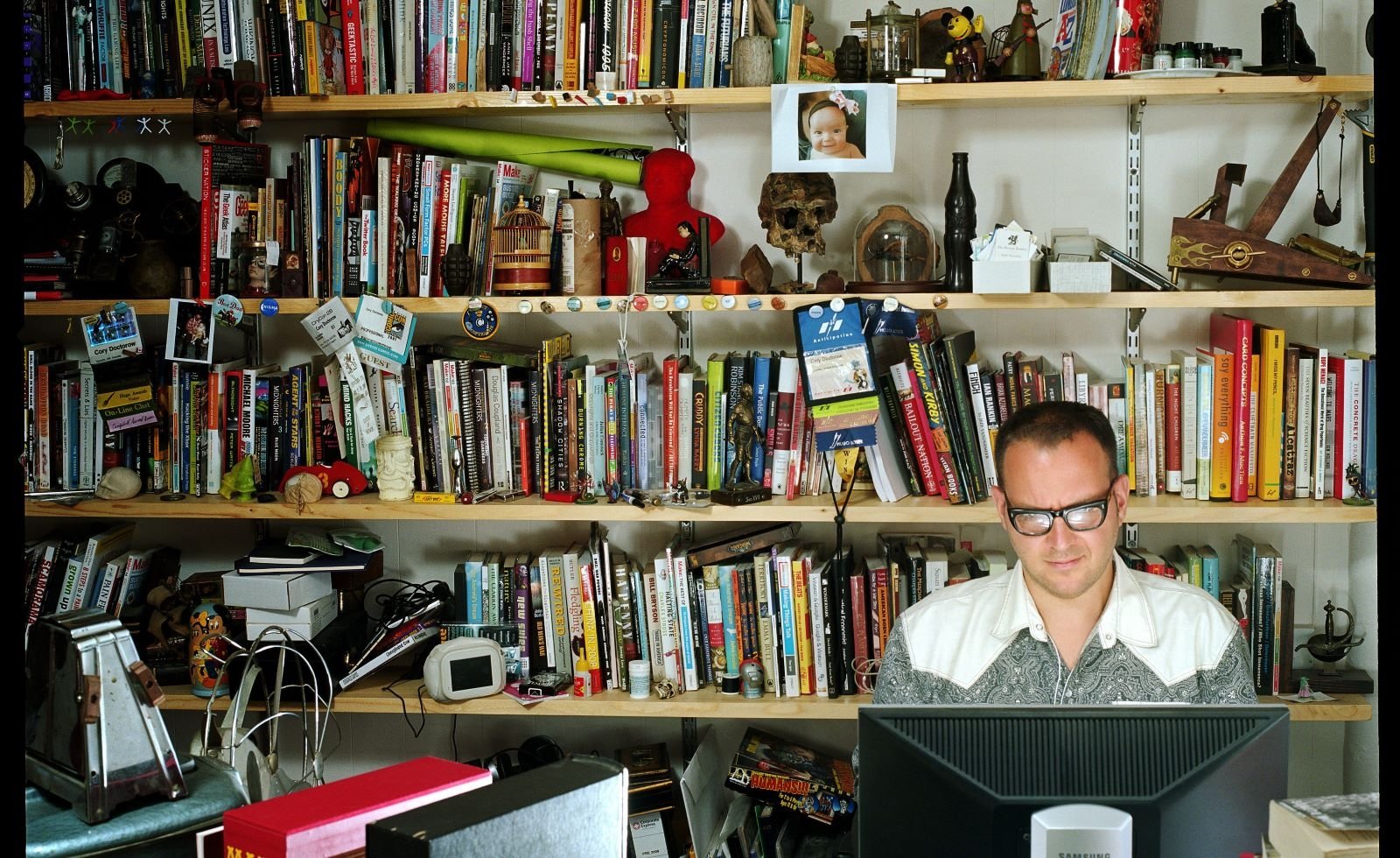

The Toronto-born blogger and author has long been at the forefront of digital discourse, as an activist, journalist, award-winning sci-fi author and former co-editor of Boing Boing, the erstwhile most popular blog in the world. For nearly 30 years, since the internet remade the world, Doctorow has been an essential voice in the new online wilderness, outspoken and insightful about every nascent topic, from file sharing and digital rights management to the ascendancy of Facebook and tech regulation.

But Doctorow is no futurist. His interest is not in predicting the future so much as in explaining what’s happening now; few do it better than he does. In addition to naming this troubling new era, and even explaining what led to this moment, Doctorow offers solutions aplenty. His non-fiction book Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do about It is set for publication by Macmillan Publishers in October 2025, hot on the heels of his new techno-thriller Picks and Shovels, which hit shelves in January.

Recently, Doctorow spoke to The Tyee at length about platform decay, printer ink, the enshittification of cyberspace, and how to stop Big Tech and techno-fascists from downloading their digital dystopia into the physical world.

“It's just a lack of consequences that has resulted in this,” Doctorow said. “Lily Tomlin used to do these ads on Saturday Night Live where she would pretend to be an AT&T operator. They would always end with: ‘We don't care. We don't have to. We're the phone company.’

“If you're insulated from consequences, you don't have to care. So you have to make them care.”

How do we do that? Read on.

The Tyee: I'm delighted to talk to you, because you’re the guy that named the present moment: the “enshittocene.” The great “enshittening.” In preparing for this interview, I saw the term defined pretty flatly as “platform decline.” Do you think that covers it?

Cory Doctorow: As you know, I’ve spent a long time trying to talk to people about very technical, tech policy questions that are very dry and abstract, and I've had limited success, but it turns out that swearing a little really increases the penetrative capacity of these abstract ideas.

In service to that, I am extremely cool with people using “enshittification” very loosely. I think that the only way to get people to adopt a very precise technical definition of a neologism is to confine its use to a group of irrelevant insiders. So if the outcome is that 10 million people hear the word used loosely, and one million of them look up the much more strict meaning, and understand it, that's a million normies that I wouldn't have reached otherwise. I call that a victory. I'm the last person to go out and scold people for not using the word in its technical sense.

That said, there is a very detailed technical critique that hangs off of this dirty little word. It describes the symptoms of enshittification and what it feels like to use an enshittified service, where first, they're good to their end-users, but wait till the users are locked in, and then make things better for business customers, and get them locked in. And then take away all the value except for the least amount of residue that they reckon will keep people locked in and deliver all the value to shareholders and executives and then go through a prolonged senescence, or, if we're lucky, a collapse.

So that's what enshittification is. We can observe that from the outside with Facebook and Twitter and Google Search and Amazon and a lot of other services.

But I think that what's more important, especially with respect to this current moment, is the mechanism that allows enshittification to happen, which is a thing I call twiddling: changing the prices, the search results, the recommendation systems, on a per user, per interaction basis.

Think about [grocery giant Loblaws president] Galen Weston doing Les Mis LARPing and raising the price of bread. That was a pretty crude trick and it was very easy for people to detect. But if every person who buys bread gets a different price, and they do so in a way that can't be compared, and if every time you visit you get a different price, it's a lot harder to catch it.

We see that happening with all kinds of personalized pricing tools. There's a company called Plexure in the McDonald's investment portfolio that advertises that it can change prices for things like drive-thrus in real time, based on surveillance data about customers. If it believes that you've just been paid, it will raise the price of the breakfast burrito you get every day.

Oh my God.

On the sell side, this happens all the time with gig apps. Uber does this with drivers, where every ride is priced differently. If you’ve been more selective about rides, they offer you more, but then once you become less selective, they start to lower it in very small increments at random intervals. It's very hard to notice until you're accepting a sub-living wage.

It's really bad here in the United States with nurses, because we have this barbaric private health-care system, and most hospitals are now staffing nurses through one of three apps that have replaced a large number of agencies. Because the apps have the market sewn up, they can do all kinds of tricks. If a nurse tries to book a shift, the app contacts a data broker and attempts to determine whether that nurse has a lot of credit card debt and whether it's delinquent. If it is, the nurse gets offered a lower wage because people who have imminent debt are more likely to accept a lower wage. Again, because every nurse gets a different wage every time they visit, it's very hard for nurses as a body to detect that their wages are falling.

Twiddling is an important component of enshittification, and what we've seen in the last couple of years is the expansion of twiddling into real-world, hard goods and physical service provision. It used to be limited to things like search results or e-commerce purchases. Now you have things like electronic shelf tags in grocery stores. In Norway, where they've had the highest adoption of these, they now get goods being repriced up to 3,000 times a day. This is quite alarming, because it means that enshittification, which started as a digital phenomenon, is going to become a physical phenomenon. William Gibson, in one of his novels, has this great quote: “Cyberspace is everting.” Things are turning inside out.

That sounds very bad. The acceleration of enshittification.

Obviously, these companies are run by people who've always been terrible. But all of this stuff is happening now, to all the platforms at once, because the things that used to punish them for enshittifying have been neutralized.

They've been insulated from consequences. They bought all their competitors so you can't flee to a rival service. They have captured their regulators. They don't have to worry about getting shut down by the government, or fined, or criminally prosecuted. They captured their workforce.

Finally, and this is the most important relative to what's happening in Canada today, they also got laws passed that made it illegal to disenshittify the things that they enshittify. Most notably, the U.S. trade representative went around the world and got anti-circumvention laws passed that make it illegal to modify technology without permission.

So open technology like the web is replete with disenshittifying add-ons. Ad blockers are running in more than half of all web browsers in the world. It's the most successful consumer boycott in human history, but there are zero ad blockers running in apps, because you have to reverse engineer the app first, and that's illegal under use of Bill C-11 and under the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and Article 6, the copyright directive.

What this means is that these companies get to be too big to fail, that they become too big to jail, and then they become too big to care, because there's no consequences for hurting us.

You recently criticized the tit-for-tat tariff war as “the stuff of 19th-century geopolitics.” Your suggestion, instead, was to bring technological self-determination back to the people by attacking anti-circumvention. Can you unpack the move a little bit? Instead of just doing our own tariffs, how should Canada respond?

Retaliatory tariffs are a very blunt instrument. They punish all the sectors of the U.S. economy equally. Tariffing soybeans just hurts some poor farmer in a state that begins and ends with a vowel and never hurt anyone. The primary effect of tariffs is to make things more expensive for Canadians. The other name for things becoming more expensive is inflation. The lesson in the last two years is that every electorate in the world really hates inflation, so it's a very politically risky move.

But we have to understand that America exports a wide variety of products, many of which are tech products, but many of which are just products with tech in them, like tractors or insulin pumps or ventilators or cars. And that their makers use the fact that it's against the law to reverse engineer and modify this modern digital technology to hide all kinds of what you might call anti-features in them. Things that pick your pocket, with the understanding that you can't stop them from doing it.

It’s one of the most profitable lines of business that these companies have, these rent-seeking businesses. For example, farmers are expected to fix their own John Deere tractor. If your tractor breaks, you install the part that should get it back to working order. But it won't actually start working until a John Deere technician travels to your farm, charges you hundreds of dollars and types an unlock code into your keyboard.

Right. You’re completely trapped.

That’s just pure rent-seeking, and it represents not just a kind of insult to farmers, but also a threat to the food supply. In the event that you can't get a John Deere technician to your farm, say, because there's a giant storm about to sweep through, and every farmer is trying to bring their crops in to salvage what they have, and there's just a limited supply of John Deere technicians to go around, or because there's a pandemic and travel is no longer practical, or because the U.S. has ordered John Deere to stop fixing Canadian tractors because of the trade war, we're left without any choices. Jailbreaking things is a very good idea on an economic but also on a political and national security level.

Companies won’t stop enshittifying customers’ experiences, says Doctorow, until their power is drained. ‘They've been insulated from consequences. They bought all their competitors so you can't flee to a rival service. They have captured their regulators. They don't have to worry about getting shut down by the government, or fined, or criminally prosecuted. They captured their workforce.’

Photo by Jonathan Worth.

Companies won’t stop enshittifying customers’ experiences, says Doctorow, until their power is drained. ‘They've been insulated from consequences. They bought all their competitors so you can't flee to a rival service. They have captured their regulators. They don't have to worry about getting shut down by the government, or fined, or criminally prosecuted. They captured their workforce.’

Photo by Jonathan Worth.

It’s not just John Deere tractors that do this. My favourite, which is to say least favourite, example, is printers. Because it's against the law to modify a printer. All of the printer companies, and there's just three or four of them, have now started building printers that check to see whether you're installing third-party ink. If you are, the printer refuses to use them, and because you can't get third-party ink for your printer that works reliably, they've been able to raise and raise and raise the price of ink.

Inkjet printer ink is now the most expensive fluid you can buy as a civilian without obtaining a special permit. It runs more than $10,000 a gallon. You print your grocery list with coloured water that costs more than the semen of a Kentucky Derby-winning stallion. It’s bonkers. It's just bad policy-making.

And as you said earlier, in Canada we just allowed this legally?

Maybe here it's worth talking a little about the legislative history of this law. So this is Bill C-11, back from 2012. The U.S. trade representative had been harassing Canada for more than a decade to adopt a law like this, and they tried to get the Liberals to do it. Sam Bulte, who was parliamentary secretary for heritage, tried to ram it through, and it was so unpopular that she lost her seat in Parkdale. Peggy Nash became the NDP MP in a Liberal stronghold because everybody hated this stupid idea that Sam Bulte was pushing. Then the Tories tried to do it, and they failed when Jim Prentice was the guy pushing it, and then [under Stephen Harper, Conservative MPs] Tony Clement and James Moore took it over.

People really hated the idea, and they were trying to diffuse some of that political rage, so they decided they would consult on it as a way to kind of make it seem like they were listening. So then they did this consultation, and it was a catastrophe here for them. More than 6,000 Canadians wrote saying that they thought this was a terrible idea, and here's why. Then 53 entities responded with comments approving of the policy. James Moore went and gave a speech at the International Chamber of Commerce in Toronto, where he said that he was going to throw away 6,130 objections, because they were the “babyish views” of “radical extremists.” And he just threw it away!

This is not a law that Canadians wanted. We got it because the U.S. said that we couldn't have free trade with them unless we passed it. It was passed against overwhelming opposition, and now we don't have free trade with America. So this is the moment to reconsider this law.

This is one of the problems that I see with any kind of tech-savvy response. Obviously, Mark Carney can do business, everybody knows that about him. But he’s old, everyone’s old, and it often seems like we really have no elected leaders who can champion this cause because they don't understand it.

My concern is that these are policy changes, and it's so clear, when you look at, say, Bill C-11 and others that tech policy — inasmuch as there's really ever been any — needs to be changed, rewritten, adapted, something. Every day we get further and further away from the world of, like, the founders, where ponies deliver mail to houses a mile apart. But you wouldn’t know from Parliament. It feels like we're playing the original version of Trivial Pursuit, which is just insanely out of touch with the modern world. We need a system update.

What do you know about John Diefenbaker? Exactly.

I wonder how we convince governments to take this stuff more seriously.*

So I am not as cynical as you are about this.

That’s great.

I'm not a Carney cheerleader. But Carney's full virtue, or his brand, is that he's a technocrat, and technocrats don't need to understand the subjects that they run. They need to understand how to set up technical or technocratic procedures for doing truth-seeking and adjudication of different policy proposals. Broadly, that looks like an expert agency that has independent experts, and there are lots of good, independent experts in Canada who can be involved in this, many of them in the civil service, who entertain proposals from the public, which includes firms, academics, activists and the general public, and then they adjudicate among conflicting truth claims.

Canada has a Parliament that, as far as I know, doesn't have any structural engineers in it, and yet we manage to make building codes that keep our buildings from falling down. There are lots of extremely technical subjects that parliamentarians have no background in, but they are able to create legislation that creates independent expert agencies, and then the independent expert agencies act in a way that is prudent and rigorous to sort through claims. Not every policy can be made that way, but this kind of policy certainly can. A lot of policy can.

So I think that there's absolutely room for a government, even a government without a single computer scientist in it, to understand and enact this policy.

Are they equipped to handle pushback, not even just from voters or other governments, but from these massive tech companies? Some would argue legislation like Bill C-18 is an attempt to adapt old-school Canadian communications policy in the 21st century. But then we get these strange outcomes, like Meta banning news on their platforms, and the Canadian government not really being able to do anything about that.

That wasn't a strange outcome. That was a completely normal and predictable outcome. It was what they did in Spain, in Germany, when they tried it there. So these were completely foreseeable outcomes. No one should have been surprised that that's exactly what they did. I think we can kind of look at tech policy as falling into two buckets. You have things like Bill C-18, which are saying to the tech platforms, “You have a lot of power, and we require that you use it more responsibly.” And then there are rules like this, where we allow circumvention, and that's about saying you have too much power, period.

The problem isn't whether you abuse your power or not. The problem is the power itself. Striking at the root of the power, which is the inability of both business customers and end-users to defect from platforms that abuse them.

Imagine if Facebook dropped all the news, but the Canadian government made it legal for Canadian social media alternatives to Facebook to circumvent their app, so that if you leave Facebook and start using another app, you can still scrape all the messages waiting for your old account and have them go to your new inbox. This is actually what Facebook did to MySpace.

So now Facebook users are no longer on Facebook. They're all using another service, and to the extent that they have friends who are still stuck on Facebook, they can keep in touch with them. But Facebook has become a commodity feed for something made in Canada.

If you want to focus the attention of Facebook executives who are making decisions about whether they're going to enshittify the platform, what you need to do is implicate their personal net worth in the consequences of making a bad decision that harms users at the expense of the company.

In Part 2 of our wide ranging conversation we pivot from policies to the personal, including what's needed for us to have a healthier relationship with all things internet.

*This article has been amended to remove a comment about the Cabinet of Canada lacking a dedicated tech minister. At the time of the interview, this comment was true, but Toronto Centre MP Evan Solomon has since been appointed minister of artificial intelligence and digital innovation. ![]()

.png)