More than 50 years after his death, Bruce Lee remains one of the most visible and beloved Asian American figures. When Americans are asked to name a famous Asian American, Bruce Lee’s name often comes up first (the only person mentioned more often is Jackie Chan, who is not American and frankly has Bruce to thank for his career—you can see him as one of the henchmen in Enter the Dragon). Even though I didn’t grow up watching Bruce Lee films, his reputation was well-known in my household. My older brother worshiped him and on occasion used his moves to put a few middle school bullies on notice: “Don’t mess with me, I know kung fu like Bruce Lee!”

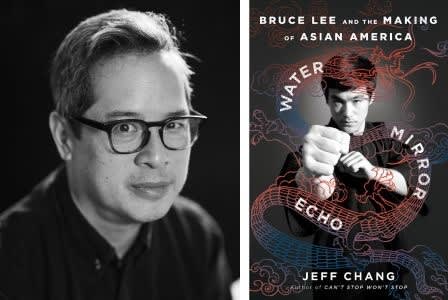

My own fascination with Bruce Lee has been a slow-burning fire over the last few years, inspired of course by my research on Anna May Wong. The similarities between their careers are revealing, and Bruce’s work and legacy has been the subject of at least two posts on this newsletter. Which is why it was a real honor when Jeff Chang, the author of a new biography on Bruce Lee, introduced himself at a book talk I did at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center this past spring. I’d heard about his forthcoming book, Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America, and I was eager to talk to him about it.

We’re several conversations in now and still haven’t exhausted the well when it comes to the legend of Bruce Lee and the striking parallels to his predecessor Anna May Wong. In fact, we thought it would be fun to continue our discussion of these two Hollywood dragons (both were born the year of the dragon) with a live audience—you can catch us this coming Wednesday, September 24, at the Center for Brooklyn History. Jeff and I recently chatted about some of the interesting facets of his research on Bruce Lee and a few little known insights about the man behind the myth.

Your work—whether it’s the award-winning Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, a cultural history of hip-hop, or Who We Be, a book that looks critically at the “colorization of America”—sits at the intersection of pop culture, politics, and race. This is also true of your new biography of Bruce Lee, which is much more than a biography; it’s also an exploration of the making of Asian America, as the subtitle states. How did Bruce Lee enter your life? And what compelled you to write this book?

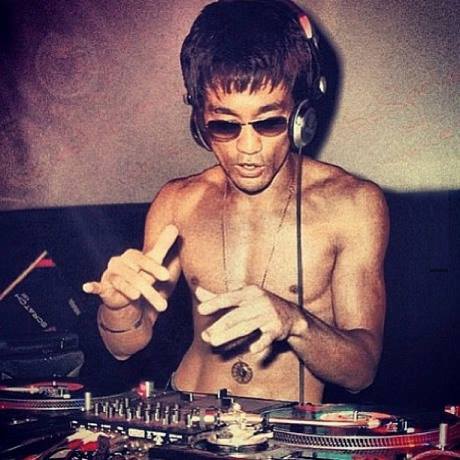

Just as my sons don’t know a time before hip-hop, I don’t think I ever knew a time before Bruce Lee. I was watching Sesame Street when Bruce was first hitting the theaters. I was part of a generation of kids who were first exposed to Bruce on television. I was also part of a cohort of Asians and Pacific Islanders in America who always had Bruce as a hero to look up to. When we started coming of age in the early 90s, that viral photoshopped image of Bruce getting ready to rock a pair of turntables was kind of the perfect mashup of who we were and how we saw him—a paragon of taste, power, and cool, and nice with the hands, untouchable.

So not long after Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop came out, a young Asian American editor named Junie Dahn approached me and literally told me, “I figured if you could do a book on hip-hop, you could do a biography of Bruce Lee. What do you think?” It took me seconds to say YES.

And lucky for us you did! I love the opening to the book—you describe a pivotal moment in The Big Boss, the film that made Bruce Lee a star in Hong Kong. I happened to watch that film for the first time a few days before I picked up your book, so the scene was still fresh in my mind. Your language captured it so perfectly that I think it’s worth excerpting it here:

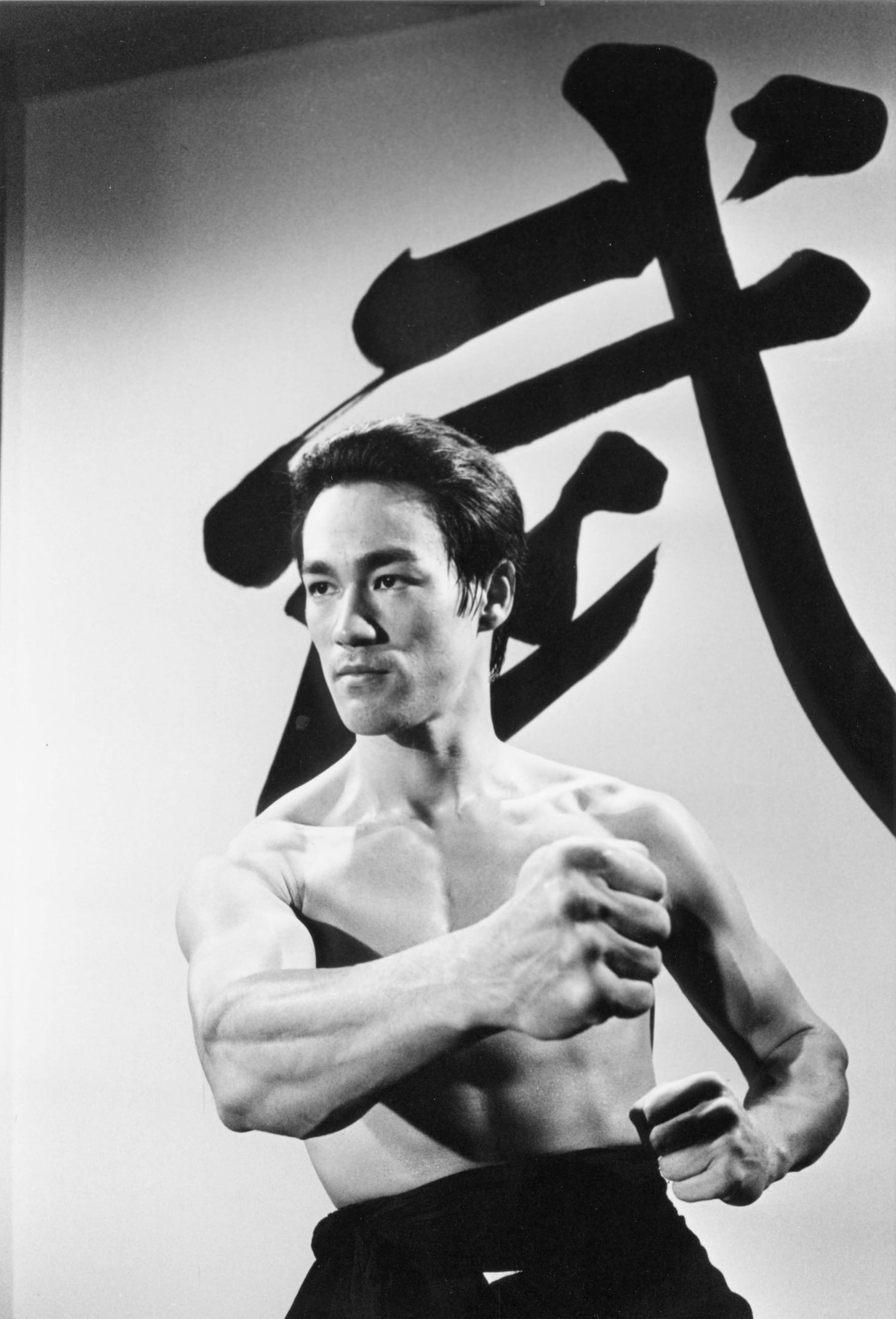

Picture him, rising from stillness to movement.

Wearing a jade pendant around his neck, a sign of a promise he has made to his mother that he will not engage in violence. Watching as his fellow workers are pummeled by thugs paid for by his boss. Taking a stray punch and turning his cheek, flush with rage.

His chain is severed. Jade pendant shattering on the concrete. Released from his pacifist vow, his face contorts, he lets out a wildcat scream and explodes into motion.

With a back crescent kick he drops a man. Flattens another with a roundhouse kick and an elbow. Stomps his foot into the chest of a third. Whips around to finish him with a hook kick.

Nine men line up against him.

He waves a finger. “You bastards can’t push us around.”

Bruce Lee had such a physical presence. Did you have to develop a new vocabulary to be able to write about his films and his physical prowess as a fighter, which are both visual phenomena? How did you think about translating Bruce’s magnetism onto the page?

What a great question! Coming up writing about hip-hop—not just the music, but dance and graffiti and all the other forms it took over—I was always confronted with translating the excitement of the culture into non-cliched words. I feel like I failed almost all of the time. With Bruce, I worried about whether it might be the same. There’s a great line in one of my favorite records: “Some people use the word ‘funky’ too loosely, and just how rappers say they ‘kick it like Bruce Lee’?”

So in this passage, I turned to the greats. “Picture him” was inspired by the first scene in my friend Bao Nguyen’s documentary Be Water. The spareness and cadence of the lines about his movement were me trying to channel Rakim in “My Melody.” And the detail of the jade pendant took on a whole different meaning when I read Helen Zia’s reporting on the 1982 racist killing of Vincent Chin. She noted that when his friends found him, his jade pendant had been broken, and that they knew that was a horrifying omen.

I know you know this intimately—when you surrender to the story, you can’t control the associations you make, and your job becomes to carefully and respectfully assemble the pieces you’ve been gifted by all the teachers you’ve had, whether you knew them and they touched you one-to-one or you received it across time and space as you interacted with their work.

Biographies require a ton of research (which I found out the hard way!). A lot has been written about Bruce Lee, including rumors about his love life and whispered conspiracy theories surrounding his death at 32. What was your research process like? How did you go about separating fact from fiction and man from myth? You were also able to work directly with the Lee family and draw upon their archive. What was that like?

Yes, I hear you. For me, it was a process of amassing secondary and tertiary sources for years before having the chance to really get to know and speak to those who knew him closely and intimately. Those who knew him dispelled fiction from fact and painted a picture of who he was. A major problem for me was that by the time I could really become engaged with the project, many of Bruce’s closest friends had passed away. So I spoke to whomever I could, and they were all incredibly generous with their time, memories, and experiences.

But the book could not have become a book without Bruce’s unmediated voice. I was incredibly fortunate that Shannon Lee chose to entrust me with access to her family’s archives. I’m eternally grateful for that privilege. There, I finally began to see the man who has been hidden beneath the mythology all these years.

Bruce was an inveterate reader, a copious notetaker, and during many significant parts of his life (although not all), a diarist. Over the years a fair portion of his notes and writings have been reprinted in books like The Tao of Jeet Kune Do and, most prominently, a series of books for Tuttle edited by John Little.

This collection of writings has helped us to understand what a synthetic and original thinker he was, but perhaps not in the way we have thought about him. He has been credited for many epigraphs he didn’t create. “Be water” is, of course, the most prominent of them. I truly don’t blame Bruce or his documentarists. Young Bruce was a brilliant synthesist with an undergrad’s disdain for citation. Who likes footnotes but researchers like us?! Often he copied quotes unattributed. He never intended for his notes to be published, after all!

A new generation of Bruce scholars has begun carefully cataloguing the sources of many of his most famous lines. Now, don’t get me wrong, Bruce’s prose could sometimes be powerful and soaring. But this recent turn has been a good correction and it helps us understand the particular way that he was a true original.

Bruce lived at a time when there was a particular American fascination with Asia and the Pacific, part of the larger imperial and military engagement. In this context, his idiosyncratic merger of ideas from Asian philosophy with ideas from the Asian fighting arts was just what the masses were seeking. To me, it is indisputable that he is one of the twentieth century’s great popularizers of Asian ideas—alongside those scholars he studied like Alan Watts and Daisetz Suzuki.

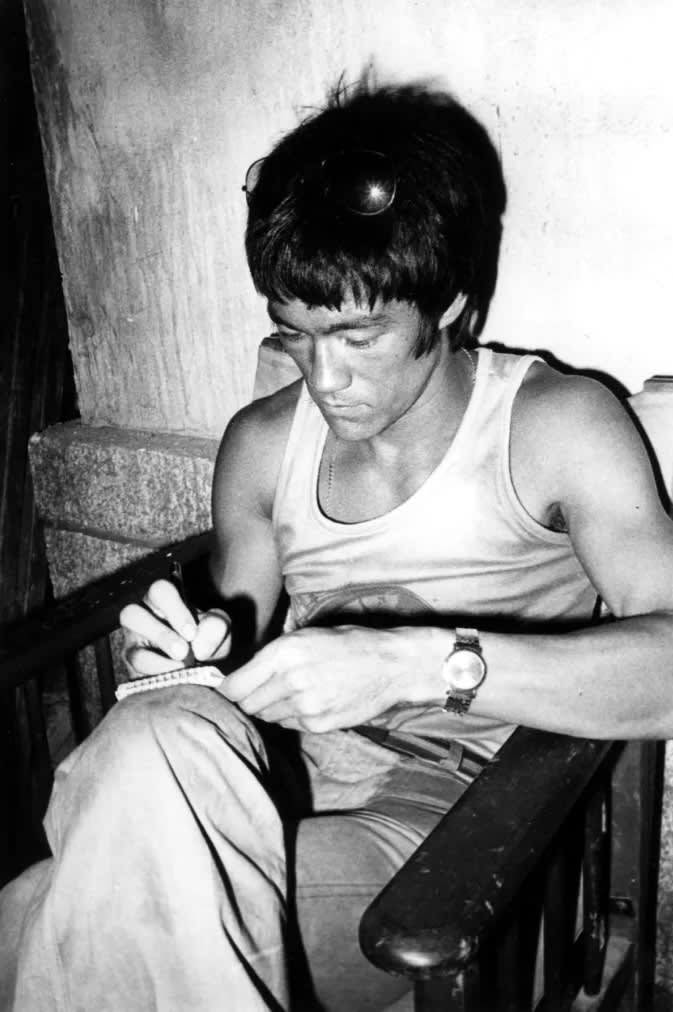

Spending time with his family and friends and with his papers helped me to understand and try to recreate the world that Bruce walked through. I was searching for the man beneath the transcendent hero. My aim was to try to create a portrait that felt psychologically and historically true. The two are related—he was a product of his times as much as he would come to shape them.

One thing that has always struck me about Bruce Lee is his absolute belief in himself, which sometimes bordered on arrogance. He didn’t just set out to become a star; he felt he already was one and that it was more a matter of getting others, specifically Hollywood, to see that. This is something he has in common with Anna May Wong (in addition to the fact that they were both dragons according to the Chinese zodiac). Against all odds and in spite of the naysayers who said they weren’t worthy, weren’t star material—often because they were Asian and seen as other—they each persisted in pursuing the thing they felt destined to do. Having studied Lee for years now, where do you think his conviction came from? And was there a cost to it?

Yes! Bruce and Anna May Wong shared that Dragon-style Main Character Energy! They both felt compelled to pursue their greater ambitions with a sense of self-belief that exceeds most of us. But actually I was also stunned at how lonely and vulnerable he often felt. This comes through in his Chinese-language writings, which seemed to be where he hid his deepest doubts. It blew me away to see a notepad he brought with him after he was sent away from Hong Kong at age 18. He had written down a bunch of four-character chengyu idioms as if he was trying to memorize them. Perhaps he had a conversation with another Chinese person where they were bunking in the bowels of the ship, or perhaps, in his fear about what was going to meet him on the other side of the Pacific, he had tried to conjure all these sayings his father had been trying to inculcate into him when he was a rowdy teen. But they are sayings like, “Don’t try to be too clever, you’ll make a fool of yourself,” or “Forgive others their mediocrity, but never yourself.”

At the end, Bruce clearly felt the weight of following through on his great ambition—the idea of representing Asians in a way that they could be proud and the idea of becoming a star had merged in his mind. He took on all kinds of battles in the last seven months of his life to protect his integrity and the dignity of the Asian and the Asian American in what became his final movie, Enter the Dragon. They took their toll, some would say the highest toll imaginable.

Last year while I was in Seattle for a book event, I had the chance to visit Bruce and Brandon Lee’s graves at Lake View Cemetery. Unlike Anna May Wong’s grave, which is in a somewhat forgotten cemetery in Los Angeles, there was a constant flow of visitors, people of all stripes and generations. It was truly impressive how many people were there to pay their respects. I couldn’t get a moment alone. How does Bruce Lee’s legacy live on today and continue to influence the culture?

Bruce remains the global hero of the underdog. It’s like Be Water’s first image of dust in the light against the theatre’s dark—for anyone who has felt ignored or oppressed, Bruce remains a projection of hope and ambition. It’s amazing to me that for three generations, he has been an icon and that my sons’ generation even now is remaking Bruce in their own image.

I know it’s always hard to pick just one, but do you have a favorite Bruce Lee movie?

Wooooow, that’s really hard! Enter the Dragon was the first, and The Way of the Dragon has the best fight scenes, but the one that continually gives me the most satisfaction is Fist of Fury. I’m a sucker for an anti-colonial anti-hero and also doomed lone-wolf narratives! I hope people get to see The Orphan sometime as well, his last teen movie he made in Hong Kong before going to the States. He gets to work his comedic skills and dances a mean cha-cha!

Water Mirror Echo, Jeff Chang’s biography of Bruce Lee, releases on October 23. Preorder the book here or from your local independent bookstore. If you’re in the New York area, join Jeff and me in discussion about Bruce Lee and Anna May Wong at the Center for Brooklyn History on September 24. I’m sure we’ll have a lot to talk about! You can follow Jeff’s book tour on Instagram and his website. Don’t forget to check out his series of shorts “Ten Ways to See Bruce Lee.”

.png)