Today I want to mostly take a break from politics — but only mostly, because these days everything is political. Instead, I’m going to talk about versions of urbanization, inspired by a Wall Street Journal article about Atlanta.

Before I get there, in Saturday's post — a conversation with Henry Farrell — I neglected to link to Henry’s own, fascinating Substack. His latest post is a follow-up from our conversation.

OK, Atlanta.

As the Journal says, metropolitan Atlanta has experienced rapid population growth ever since the introduction of air conditioning. Why? In general, every metropolitan area has some kind of core competence that powers its economy — finance in New York, technology in the Bay Area, and so on. Figuring out what Atlanta does for a living is a bit tricky: What do Coca-Cola, Home Depot, UPS, and Delta have in common? But my guess is that it’s largely about logistics, with Hartsfield-Jackson Airport — the world’s busiest — playing a key role.

But Atlanta’s growth has been slowing recently, and last year, for the first time since these data started being collected, net domestic migration went negative. It’s a small decline, but startling for a city that was for decades a magnet for Americans leaving both small towns and coastal cities.

Why is Atlanta’s boom petering out? The Journal, and many other discussions, focus on two problems: Affordability and traffic. Both problems are clearly visible in the data. And I’d argue that they’re closely related. What we’re seeing in Atlanta, I’d suggest, are the limits of sprawl.

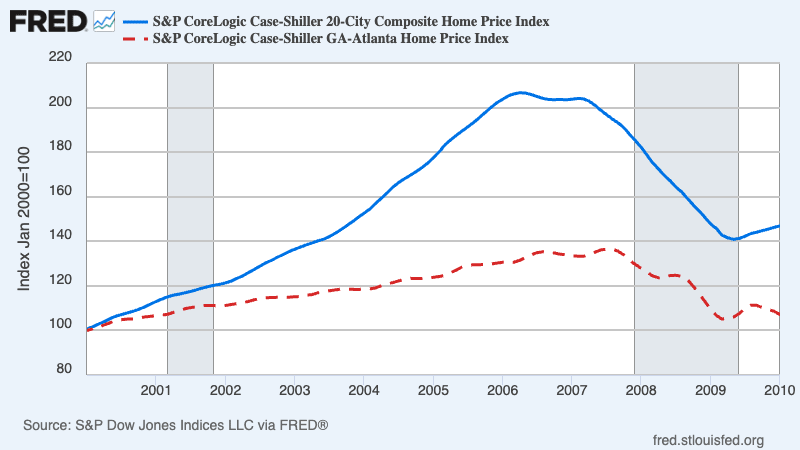

Start with affordability. To be honest, the last time I even thought about housing prices in Atlanta was during the 2000s housing boom and bust. Back in 2005, when I warned that we were facing a major housing bubble that was beginning to deflate, I suggested that we think of Atlanta as part of Flatland — the central part of the country, where the relative absence of land-use restrictions made it easy to build more housing when demand increased:

When the demand for houses rises, Flatland metropolitan areas, which don't really have traditional downtowns, just sprawl some more. As a result, housing prices are basically determined by the cost of construction. In Flatland, a housing bubble can't even get started.

Indeed, Atlanta was basically insulated from the 2000s housing price bubble, and suffered only a modest price decline in the aftermath of the financial crisis that occurred after that bubble burst:

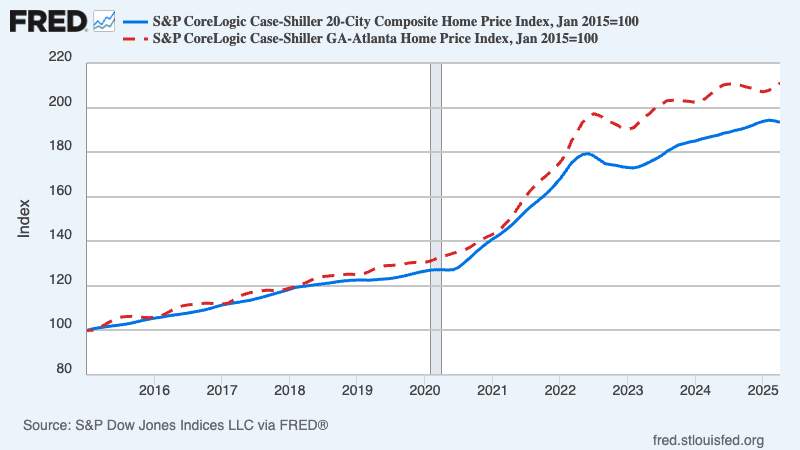

But Atlanta has not been insulated from the big runup in prices over the past decade. In fact, Atlanta prices have risen somewhat more than the national average:

What happened to the ability to “just sprawl some more”? That, I suspect, is where traffic comes in.

Atlanta has terrible traffic. According to Consumer Affairs, it now has the fifth worst traffic in America, edging out New York — which is pretty amazing given that even now the New York metro area has more than three times Atlanta’s population. As one of the people quoted in that Journal article jokes, “Atlanta is exactly an hour from Atlanta.”

I’ll be curious to see how New York’s stunningly successful congestion charge will affect this picture in the years ahead.

To be fair, Consumer Affairs gives New York an edge because its index takes traffic fatalities into account, and New York has fewer than half as many fatalities per capita as Atlanta. As some of us keep saying, NYC is remarkably safe for an urban hellscape.

But its not just that New Yorkers are less likely to die in car crashes. New York and Atlanta drivers have almost exactly the same average commute time — 31 minutes. Again, how is that possible when New York has three times Atlanta’s population?

My answer is that New York makes far more extensive use than Atlanta of two cutting-edge transportation technologies. One of them is this thing called a “train,” sometimes running underground. The other is something called an “elevator,” which allows many people to live in multistory, multifamily apartment buildings.

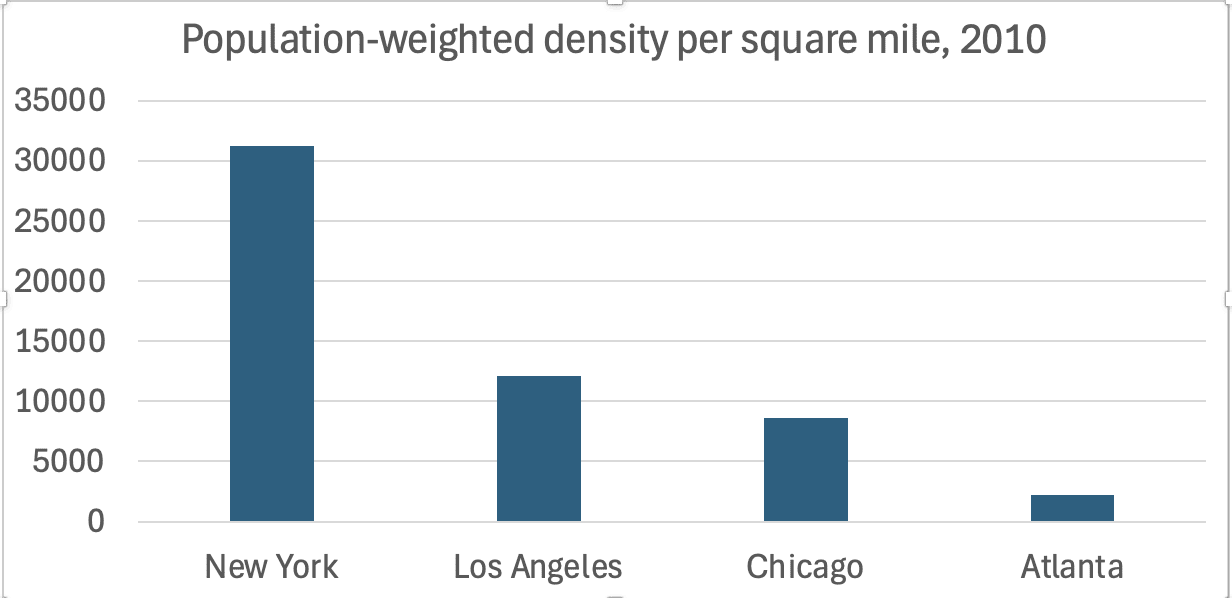

Apartment living, in turn, permits New York to have much higher population density than Atlanta.

My preferred measure is “population-weighted density,” which asks how densely populated a neighborhood — strictly speaking a Census tract — the average person lives in. The Census calculated this measure after the 2010 Census, but unfortunately doesn’t seem to have continued the practice or even maintained the data on its website. But I was able to retrieve it using the Wayback Machine. And the 2010 data showed New York in a class of its own, even among our biggest cities, while Atlanta was the Sultan of Sprawl:

By the way, I live on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, which has about 60,000 people per square mile. If you think that means that there must be teeming crowds everywhere, you’re wrong. The main north-south streets are busy, but the side streets are surprisingly quiet. True, there’s always the faint sound of a car alarm going off somewhere in the distance, but you get used to that.

Not everyone wants to live that way, which is OK. The point is that in the New York area people can live that way, if they choose, which many do. In Atlanta, they often can’t. Red states generally have many fewer obstacles to home construction than blue states. But one thing you aren’t allowed to do in much of Atlanta is build multi-family housing, which means that the metro area has low population density.

New York’s high population density makes its traffic less terrible than you might expect for a city that size, for a couple of reasons. One is that a dense population supports public transit, and not just trains: Buses can run more frequently, which makes them much more attractive to commuters.

The other is that slow driving speeds don’t matter as much when you don’t have to drive very far to get someplace useful or interesting. According to the TomTom traffic index, the average speed of traffic in Atlanta is still more than twice what it is in New York. But given New York’s high density, the places you want to go are generally much closer there than they are in Atlanta. As I mentioned, average commute times by car are about the same in the two cities. And once you take subways, commuter rail and frequent bus service into account, I’m pretty sure that it’s easier on average to get around New York than it is to get around Atlanta.

What does all this have to do with housing prices? My hypothesis — which I’m happy to have corrected — is that this point Atlanta can no longer easily add housing by just sprawling some more. Why? Because given bad traffic and the lack of alternatives to driving, sprawling some more means locating so far out that you lose the advantages of living in a major metropolitan area.

None of this should be taken to mean that New York, or blue cities in general, are getting it right. Nimbyism and overregulation remain huge problems. But what’s happening to Atlanta suggests that red cities have their own problems, that hostility to multi-family housing and disdain for public transit can also create an affordability crisis.

It is possible for big cities to get it right. America could, for example, learn a lot from Tokyo. But I don’t expect to see that happening any time soon.

MUSICAL CODA

.png)