Carl Hagenbeck believed that animals should be housed in habitats that mimicked their natural environment. Earlier, he’d followed the same guiding philosophy when exhibiting Indigenous people in “human zoos”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Shoshi_Parks_headshot.jpg)

Shoshi Parks - History Correspondent

June 20, 2025

At the turn of the 20th century, the great zoological gardens of Paris, London and New York City would have been hardly recognizable by today’s standards. Animals large and small—those that had evolved to sprint across plains and live half their lives submerged in water—were confined in rows of tiny, barren cages lined with metal bars. “They were often on their own and had nothing natural in their enclosures,” says Karen S. Emmerman, an expert on animal ethics at the University of Washington. At a time when it was difficult to keep exotic animals alive, let alone healthy, in such constrained conditions, giving the creatures freedom to roam outdoors was viewed as a death sentence.

But Carl Hagenbeck, a German animal trader and entertainment impresario, had a different vision of what zoos could be. These animals, he argued, should be able to engage in innate behaviors “in an environment which differed as little as possible from [their] own natural environment.” Ibexes needed mountains to climb. Lions needed grottos for bathing.

When Hagenbeck opened his Tierpark Hagenbeck in Hamburg, Germany, in 1907, it was unlike any zoo seen before. Instead of small indoor cages, he “recreated the natural landscape of faraway places,” says Nigel Rothfels, a historian at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the author of Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Hagenbeck built “living habitats”: large outdoor enclosures with sturdy fake rocks and shallow artificial pools. He replaced cage bars with moats and dug deep pits that could be observed from above. He created the perception that the animals, while not exactly free, were living authentic lives that mirrored their experiences in the wild.

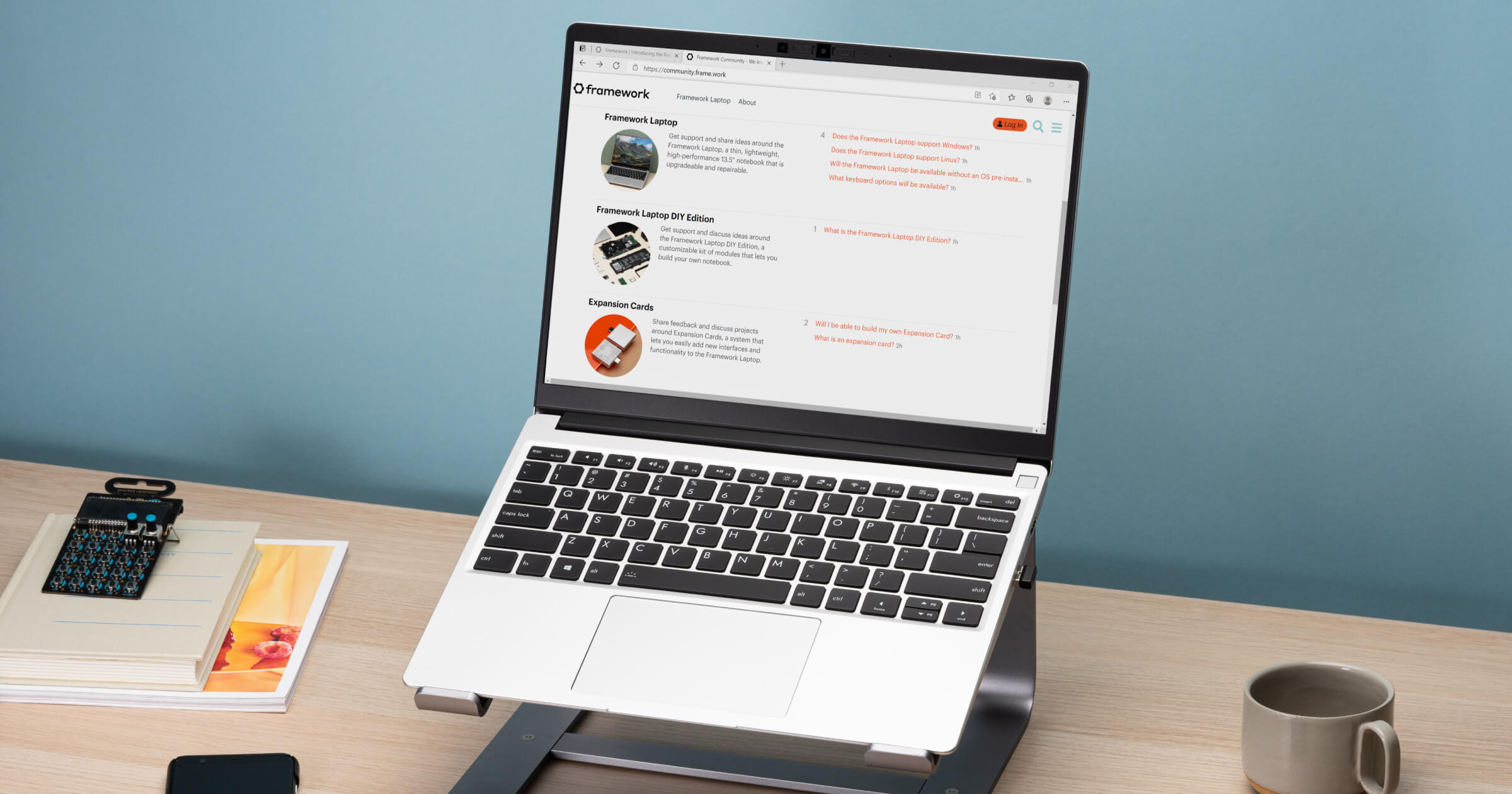

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/04/fa0434f5-5a7b-4857-ba2a-b8c3be1d65fc/beasts_and_men_being_carl_hagenbecks_experiences_for_half_a_century_among_wild_animals_1912.jpg) Water birds in a naturalistic zoo habitat

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Water birds in a naturalistic zoo habitat

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Visitors loved the innovations, and over the next several decades, the so-called Hagenbeck revolution spread, transforming zoos around the world in the image of Hamburg’s Tierpark. More than a century later, “living habitats” are still a hallmark of modern zoos. But while Hagenbeck traded, trained and showcased animals his entire life, it wasn’t elephants or lions that led him to recognize the need to display exotic species in quasi-natural ecosystems. Hagenbeck first tested his ideas on human beings.

Before there were zoos, there were menageries, collections of living animals that were housed in the gardens of European royalty. Once reserved for aristocrats, these menageries opened to the public in the 17th and 18th centuries; commoners could also attend performances hosted by itinerant showmen who traveled from town to town with exotic species in tow.

By the mid-19th century, zoological gardens had shifted from manifestations of elite status to symbols of power and progress for European cities growing rapidly by the light of the Industrial Revolution. Because zoos required global acquisition networks and extensive funds to maintain, building them became an expression of a city’s political and economic influence. Soon, they were popping up across the continent and in many urban centers in the United States, too. (The Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park—now the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute—opened in Washington, D.C. in 1891.) “If you’re a legitimate city by the end of the 19th century, you better have a zoo,” says Rothfels.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/be/c6be837c-af6b-4cb4-9ff4-42095c8b7006/carl_hagenbeck_ca_1890.jpg) Carl Hagenbeck, circa 1890

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Carl Hagenbeck, circa 1890

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hagenbeck supplied the majority of the wild animals that ended up in Europe’s first public zoos. Lanky, with a stoic demeanor, he traced his interest in zoos to his youth, recalling in his autobiography how local fishers once gave his father, a fishmonger, at least six seals they had accidentally caught in their nets. A lover of animals with a small personal menagerie of his own, Hagenbeck’s father built two large wooden tubs and opened his doors to visitors, charging each 1 shilling for a look. The family business took off from there.

In 1859, at age 14, Hagenbeck assumed responsibility for his father’s animal trade, expanding the company’s networks across Africa, Asia and the South Pacific just as a new surge in colonial exploration was carving up the globe. Soon, he was importing giraffes, antelopes, ostriches, rhinoceroses, panthers, cheetahs, birds, buffaloes and dozens of other species for zoos across Europe. In 1872, the American entertainment mogul P.T. Barnum purchased animals worth £3,000 (nearly $400,000 today) from Hagenbeck for his upcoming traveling show. Hagenbeck claimed that Barnum dealt exclusively with him for the rest of his life.

For close to two decades, the German businessman dominated the exotic animal trade. But the one-two punch of an economic downturn and the rise of a new generation of traders in Europe and the U.S. eventually led Hagenbeck down a less-traveled path. It wasn’t just the beasts of distant lands that fascinated audiences in the West, but also the curious, never-before-seen human communities caught in the crosshairs of imperial expansion. In 1874, when a friend suggested that Hagenbeck display Indigenous Sami herders alongside his next shipment of Scandinavian reindeer, the impresario needed no convincing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/23/f9/23f9388d-0bd1-477f-9182-eb6535ab4361/karl_hagenbeck_full-length_portrait_seated_on_ground_with_two_girls_chimpanzee_and_three_l.jpg) Hagenbeck poses with a chimpanzee and three lion and tiger cubs.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hagenbeck poses with a chimpanzee and three lion and tiger cubs.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous people from around the world had been displayed as spectacles in Europe since the 16th century, typically in staged performances or as sideshow acts. But Hagenbeck valued authenticity above all else. He felt that the public would be more interested in watching the Sami carry out the routines and rituals of their daily lives than in attending a contrived or dramatized show—and he wasn’t wrong.

Reflecting on the “huge success” of his first ethnographic exhibition, Hagenbeck wrote, “I attribute this mainly to the simplicity with which the whole thing was organized and to the complete absence of all vulgar accessories. There was nothing in the way of a performance.”

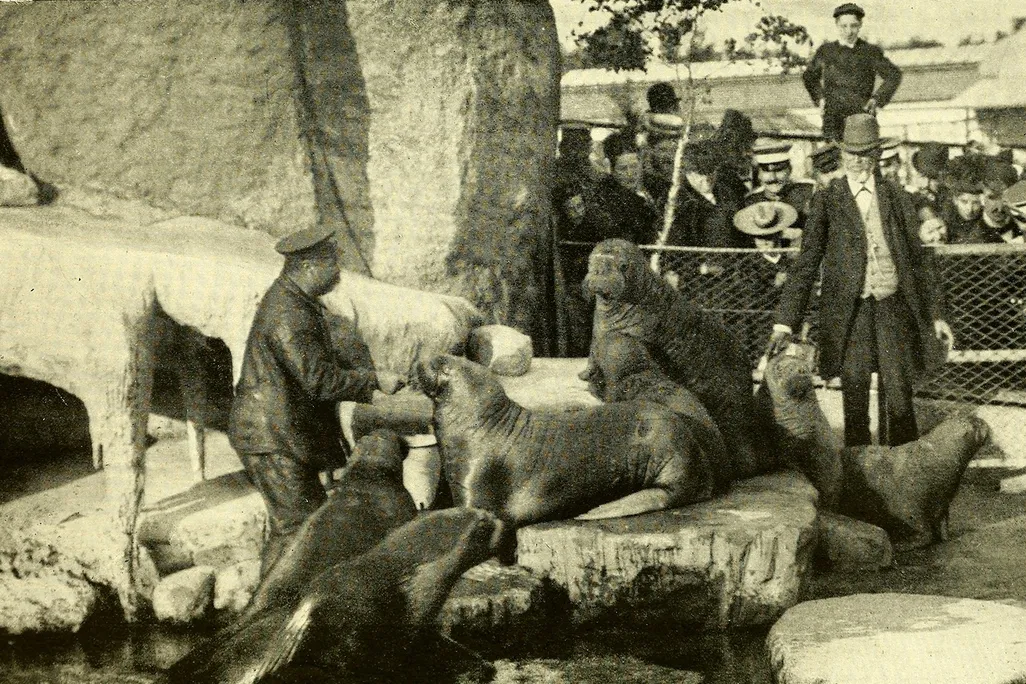

For this initial 1875 display, Hagenbeck brought two families, the Rastis and the Nielsons, to Hamburg along with their 31 reindeer and their essential items: Crates full of tools, skates and snowshoes, as well as sledges and several dogs to pull them. In an open yard behind his home, the Sami raised their tents and hung them with tanned reindeer hides sewn with sinew. They dressed in long deerskin coats and pointed fur caps, and they laid out areas for fixing equipment and preparing meals. Audiences reportedly loved to watch the families milk their reindeer, which milled about the enclosure as if it were their familiar Arctic Circle habitat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c9/d3/c9d382c7-2c3e-45f4-890a-094fd8334024/bundesarchiv_bild_183-r52035_hamburg_kaiser_wilhelm_ii_im_tierpark_hagenbeck.jpg) Wilhelm II of Germany speaks to individuals on display in a "human zoo" at Tierpark Hagenbeck in 1909.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R52035 via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0 de

Wilhelm II of Germany speaks to individuals on display in a "human zoo" at Tierpark Hagenbeck in 1909.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R52035 via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0 de

“All Hamburg came to see this genuine ‘Lapland in miniature,’” Hagenbeck later wrote. To the impresario and his visitors, the Indigenous families were “unspoiled children of Nature,” representatives of a simple, romanticized people who had long ago disappeared from European shores.

For the few weeks they were on display at Hagenbeck’s estate, the Rastis and the Nielsons attracted so many visitors that the businessman wasted little time in recruiting the next guests for his völkerschau (“people show”)—what scholars today refer to as “human zoos.” He went bigger this time, importing a large group of Sudanese men (and one woman, Hadjidje) alongside massive black dromedaries and other species native to their homeland in 1876.

Hagenbeck staged similar Sudanese “caravans,” as he called them, multiple times, attracting 62,000 people to his Berlin show in a single day, according to Rothfels. He followed up this act by displaying six Greenlandic Inuit adults and children in 1878 and eight more Inuit from Labrador, Canada, in the fall of 1880. The later exhibition ended in tragedy when every member of the group died of smallpox, a disease that Hagenbeck’s team had failed to vaccinate them against.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/89/b2/89b2bbc3-b51c-4f85-9ea7-87a0c4a90522/abraham_ulrikap.jpg) Abraham Ulrikab, an Inuit from Labrador, Canada, who died of smallpox while appearing in a Hagenbeck show in Europe

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Ulrikab, an Inuit from Labrador, Canada, who died of smallpox while appearing in a Hagenbeck show in Europe

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The individuals put on display by Hagenbeck and others like him had varying experiences. Although some were kidnapped, coerced or virtually enslaved, the majority of participants in “human zoos” had some agency and autonomy. “There are cases [where] people absolutely didn’t understand what they were getting themselves into, and [participating in these spectacles] was a deeply horrible mistake,” says Rothfels. “There are other cases where it’s pretty clear that people are having a pretty great time and are actually getting paid pretty well.”

After briefly swearing off human displays, Hagenbeck was soon back at it, this time with a group of Indigenous Kawésqar people who’d been abducted by a German ship captain in Chile’s Tierra del Fuego archipelago in 1881. Hagenbeck displayed the 11 men, women and children virtually naked, refusing to give them European-style clothing that would protect them from the cooling autumn temperatures. Unlike previous groups displayed by Hagenbeck, the Kawésqar were not accompanied by tools or domestic animals, adding to a problematic perception pushed by the day’s pre-eminent anthropologists: that the tribe was a holdover from the Stone Age, made up of “primitive” people who’d survived only because their homeland was inhospitable and remote.

“They could have progressed further if the adversity of their environment had not repressed them so much that they remained at the lowest level of social life,” claimed German physician and anthropologist Rudolf Virchow. Observing them, he believed, was akin to going back to prehistoric times to observe humanity’s ancestors.

Hagenbeck only halted the show after five of the Kawésqar died, likely of tuberculosis and measles. He gifted the bodies of the dead to a Swiss university for study and sent the living back to Chile. One died on the journey home. The Swiss university repatriated the remains of the five kidnapped Kawésqar to the Chilean government in 2010.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/46/f9/46f9ab83-384c-462e-950c-b52230f95931/kawesqar.jpg) Five Kawésqar whose remains were repatriated to Chile in 2010

University of Zurich

Five Kawésqar whose remains were repatriated to Chile in 2010

University of Zurich

Despite the deaths and his supposedly firm resolve “never to arrange human exhibitions again,” Hagenbeck continued putting people on display well into the 1880s. By the end of the decade, human zoos had taken on a life of their own. They found a welcome audience at world’s fairs, beginning with the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Scholars estimate that over just 50 years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 20,000 to 25,000 Indigenous people were exhibited in “living habitats” in the West.

The subtext of these displays wouldn’t have been lost on audiences of the time. Told that Indigenous people were evolutionarily inferior to white Europeans and Americans, visitors accepted the idea that colonialist progress would soon condemn these groups to extinction.

“Whatever their disagreements, humanitarians, missionaries, scientists, government officials, explorers, colonists, soldiers, journalists, novelists and poets were in basic agreement about the inevitable disappearance of some or all primitive races,” writes Patrick Brantlinger in Dark Vanishings: Discourse on the Extinction of Primitive Races, 1800-1930. “Savagery, in short, was frequently treated as self-extinguishing.”

No longer the only showman trading in Indigenous people, Hagenbeck complained that there was too much competition in people shows to make a decent profit anymore. Meanwhile, as the frenzy for human spectacle surged, the animal market once again stabilized. While Hagenbeck never completely abandoned the human zoo—his Tierpark in Hamburg boasted plenty of space to display Indigenous people—he reinvested his energy into trading, training and showing exotic animals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/ae/36ae88a0-899d-47fe-9ff9-8971345d3664/exposition_universelle_de_1889_groupe_de_canaques_ph19626.jpg) Indigenous people on display at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous people on display at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

For these captive creatures, extinction seemed similarly inevitable. But unlike Indigenous communities whose cultures and ways of life were considered beyond saving by the Western world, advocates of animal zoos came to believe that their most important role was not demonstrating “colonial power over colonized places,” says Emmerman, but preventing the species they displayed from disappearing forever.

The “living habitat” championed by Hagenbeck laid the foundation for zoos to begin presenting “themselves as more than merely recreation: [places whose] mission was described as conservation,” Emmerman says. Educating the public about issues like habitat loss and extinction became a primary goal.

Today, zoos are the subject of much debate, with supporters touting the work they have done to save various species and critics questioning the effectiveness of their conservation efforts. There is no doubt, however, that zoo animals are better off today than they were before the introduction of Hagenbeck’s innovations. The development of an accreditation process in the early 1970s by the Association of Zoos & Aquariums further advanced standards for zoos, establishing a set of best practices to ensure that captive animals receive proper care.

Despite his complicated legacy, Hagenbeck is widely considered the progenitor of this shift in viewing exotic animals not as objects, but as living beings with needs and intellectual abilities.

“Before Hagenbeck, zoological gardens often struggled to convince the public that it was not so bad to be an animal at the zoo,” Rothfels writes in Savages and Beasts. “Ever since Hagenbeck, animals have not been collected merely for reasons of science or education, or even really for recreation—animals have been put in zoos increasingly because they are nice, healthy, safe places to be and because the animals, we are told, might be better off there than in the real ‘wild.’”

.png)