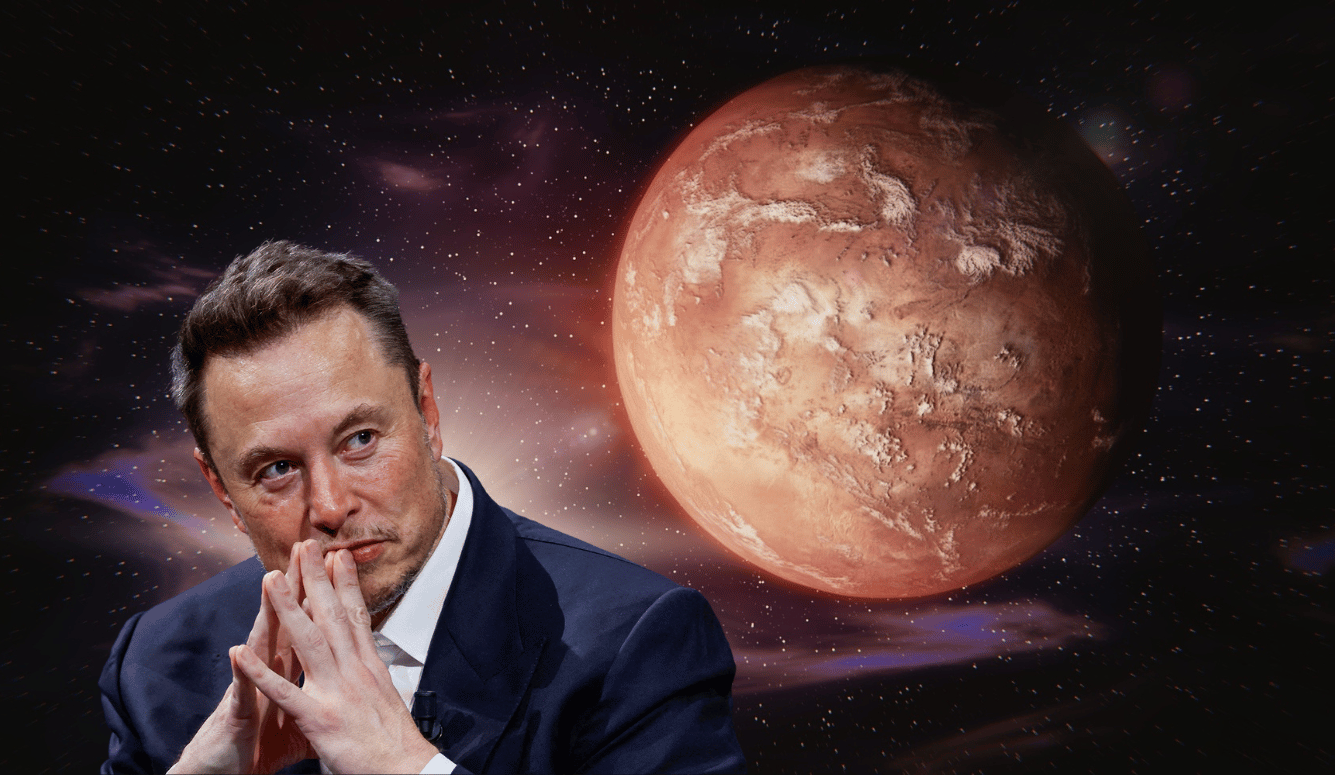

Mars

Elon Musk’s Mars plans are not just illusory, they are dangerous.

19 May 2025 · 10 min read

Reuters/Canva

Reuters/Canva

Elon Musk wants to create a permanent human colony on Mars. He has recently announced plans to land the first human on the Red Planet within this decade, with the view to establishing a million-strong Martian colony within 20–30 years. This plan is logistically ludicrous, strategically ill advised, and scientifically and politically divisive and dangerous. Musk is utilising his vast fortune to try to reshape human destiny. We need to hit pause before his plans damage the international balance in space.

While Musk has a history of making science-fiction-like claims, he has also been the most successful technological entrepreneur of our time. He singlehandedly transformed the auto industry, making electric cars a practical reality within less than a decade, and created the first new rocket engine design in the US in more than a generation, ultimately enabling private industry to eclipse NASA in their ability to deliver humans and payloads into near-Earth orbit.

I have immense respect for Elon Musk’s accomplishments and his skill and acumen as an entrepreneur. He gave me two personal tours of SpaceX, which blew me away, and I have always admired his ability to think outside the box when creating new technologies. I am not alone in this regard: given his many successes, a lot of people are willing to give him a pass when he makes outrageous proposals that don’t pan out, such as the claim that his boring company will soon allow the supersonic transportation of people in underground tunnels between LA and San Francisco, or beneath the Atlantic.

His Mars plans are dangerously different, however.

First, we should ask: why the rush for Mars now? It has been more than fifty years since humans last walked on the Moon, which is vastly simpler to access and could serve as a wonderful testing ground for construction projects in harsh extraterrestrial environments, as well as providing the perfect launching pad for future deep-space travel. Why leapfrog this natural first destination to undertake a far more expensive and risky mission to Mars?

The Case for Life on Mars

Settling Mars isn’t just about making humanity a multi-planetary species. It is about improving life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for everyone on Earth.

The rationale seems to be primarily based on bravado. This is not new. The original Apollo program was primarily motivated by a desire for national prestige. One might argue that this is just as valid a motivation for a full-court press for Mars. But current geopolitical realities suggest the opposite. China is on course to land humans on the Moon this decade. An urgent focus on Mars is likely to hamstring the current US program to return to the Moon, handing tremendous near-term technical prestige to China at the expense of the US.

But merely landing humans on the red planet is not enough for Musk; he wants to populate it. We are told that this would protect Earth’s population in case of a terrestrial catastrophe, such as a planet-killing asteroid, or a nuclear war. As far as the long-term future of humanity over the coming millennia goes, diversifying our species’ planetary habitats may make sense. But there is little or no argument for doing so within 20–30 years, or perhaps even this century. There is almost zero likelihood of cosmic impacts on this timeframe, and surely the best way to protect the human species in coming decades is to focus on resolving the tensions we face at home, from unbridled nuclear proliferation to strategic global competition and realignment. Environmental concerns like those associated with climate change will not directly precipitate the annihilation of the human species, but they could exacerbate geopolitical tensions that could lead to global conflicts, including nuclear war.

There are technical reasons to be sceptical about Musk’s plan, too. Scientifically it doesn’t make sense. To land on Mars by 2030, any crewed ship would have to be launched during the narrow window in 2028 to take advantage of a gravity boost from the Moon that would direct the craft to Mars within 6–8 months. But the current Starship design uses up almost all available fuel just reaching near-Earth orbit. As a recent Economist article has emphasised, to refuel a Starship in orbit might require 15–20 other Starship missions. But over the past two years, not one Starship has reached orbit. The last two launches of an upgraded Starship model have not gone well. Both had to be blown up before they could achieve their mission goals. To get an uncrewed vessel to Mars by 2030 would require a lot of practice, including learning how to transfer ultracold fuel from one spacecraft to another—something never yet attempted—yet with just sixteen months remaining before the 2026 launch window opens, only four test flights have been done this year.

These are the logistical impediments to getting to Mars. Getting back is a whole different matter. As I argued in the New York Times almost thirty years ago, one-way human missions to Mars make the most economic sense, given the huge cost of storing fuel for the return trip on an outbound voyage. Robert Zubrin has spearheaded the idea of using Martian ingredients to create fuel to power an already-landed device on its return journey to Earth. But that would require an infrastructure far beyond anything that we can practically achieve within the next two decades. As a result, any Martian crew would have to survive on the red planet for many years, facing an incredibly hostile environment and risking such severe radiation exposure on the Martian surface that it would make Matt Damon’s brief cinematic sojourn on the planet seem like a stay in a luxury resort. Without significant pre-existing infrastructure many, if not all, of the first successful landing crews are likely to die there.

Podcast #242: Life on Mars

Iona Italia talks to Robert Zubrin, who argues that Mars offers an extraordinary wealth of social and intellectual opportunities that would enrich humanity. And we can get there soon.

The current US Artemis program for returning humans to the Moon relies on a Human Landing System (HLS) version of Starship that also needs to be refuelled in space, and its planned 2027 human return mission timetable is also in jeopardy. It makes sense to consider abandoning this risky plan to return to the Moon in favour of other alternatives, including configuring SpaceX’s superheavy launch vehicle to launch something other than a Starship. But Musk seems to have little interest in such a project—even though its failure would mean that China would be able to land humans on the Moon, while the US could not.

Of course, Musk should spend his own personal dollars as he sees fit. But he is now closely connected to the new Trump administration, and there is growing evidence that his priorities are skewing government expenditure on space programs and space research.

As the New York Times recently reported, even before Musk assumed his new role in the Trump administration, SpaceX was already one of the largest federal space contractors, receiving over US$3.8 billion in commitments for the fiscal year 2024. But since then, Musk and SpaceX have both been readied for far greater roles. For example, there are military proposals to use SpaceX launches to ferry materials quickly around the globe, to integrate Starlink into FCC and FAA communication systems, and to use Starlink as the basis for developing rural Wi-Fi across the United States. In addition, at least four new launchpads are on the cards, as well as plans to launch up to 120 Falcon 9 rockets from Cape Canaveral each year. These projects would create financial windfalls for Musk. But, more worryingly, all this might also cause Musk’s dream of Mars colonisation to distort all NASA’s priorities.

The Trump administration has nominated billionaire entrepreneur and space enthusiast Jared Isaacman as the new NASA administrator. Isaacman paid Musk’s company hundreds of millions of dollars of his own money to take what were essentially expensive joyrides into orbit aboard SpaceX rockets. There is every likelihood that he has already bought into Musk’s prioritisation of Mars-bound human space exploration hook, line, and sinker. According to the Times, NASA officials already expect Isaacman to revamp the Artemis Moon project, and direct funds toward SpaceX, or its commercial human transport competitor, Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin.

These developments coincide with recent news, first reported by ars technica, and verified by both Science and Nature magazines, that the Trump administration is essentially proposing to disband NASA’s entire unmanned science program in favour of human space missions. This would involve cutting 20 percent of NASA’s budget, almost all of it from NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, which oversees planetary science, Earth Science, and astrophysics research.

The astrophysics directorate would be cut by two-thirds, and the overall science budget for the 2026 fiscal year would be cut by nearly half, to US$3.9 billion. This would kill, among other things, the next generation Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which has already almost been completed, on time and on budget, at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It would cut all funding for the Mars Sample Return mission as well as the DAVINCI mission to Venus. It would also effectively force the closure of NASA Goddard, where most NASA science is done.

This has been described as an “extinction level” threat to science at NASA. Almost all NASA’s most important scientific discoveries, including those made with its fleet of space telescopes, the most recent of which is the James Webb Space Telescope, involve unmanned space probes.

The Trouble with Technocracy

Elon Musk offers a good example of how technocrats don’t always get it right, and why trusting them with the world’s progress is risky.

If NASA gives up its science mission to appease the interplanetary manifest destiny notions of Elon Musk and others, this will be an unprecedentedly short-sighted mistake. As both astronaut Buzz Aldrin and I argued when we testified before Congress on the future of Space Exploration almost 25 years ago, for over sixty years NASA has maintained a careful balance between extremely costly human missions—such missions are primarily motivated by a sense of adventure, and what science comes out of them is mainly focused on learning how humans can function in space—and far less costly fundamental science missions. The current plans would effectively end that balance, and with it, the likelihood of profound new scientific discoveries in space.

The evisceration of NASA’s science budget could eventually be reversed—but at great cost to US international leadership in science. But enacting Elon Musk’s goal of putting space colonists on Mars could do more serious and longer-term damage, in this case to the global stability of our geopolitical environment here on Earth, by violating the 1967 United Nations Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, also known as the Outer Space Treaty (OST).

As detailed in a recent article in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the OST was signed during the Cold War by the US and USSR, along with the rest of the international community, to regulate the peaceful uses of space at a time when it looked like as if space could easily become the next war zone. In 1962, the US detonated a 1.4 megatonne bomb at a height of 400 kilometres, disrupting radio transmissions and phone calls as far away as Hawaii, producing electrical surges on airplanes, and damaging six satellites. The USSR followed their lead. Faced with the possibility of a new arms race in space, the international community signed the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban treaty, which ended high altitude nuclear testing, and ultimately, in 1967, the UN codified the OST.

The treaty, which has been in force for over fifty years, does not allow claims of sovereign territory or weapons of mass destruction in space. This was in line with the similar agreements, signed by all nations, on Antarctica and the Deep Ocean. Whenever technology has opened up vast new territory for exploration, land claims have been stopped, and research and environmental preservation prioritised.

Simply settling on Mars would not violate the treaty. But Musk’s plans to create a new sovereign nation on the Red Planet contravene the terms of the OST. SpaceX’s Starlink Internet service agreement stipulates: “For Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities. Accordingly, Disputes will be settled through self-governing principles, established in good faith, at the time of Martian settlement.”

The OST does not permit Martian settlers to make a territorial claim of this kind by forming their own sovereign nation. Moreover, it is likely that most of SpaceX’s Martian settlers, who would travel under NASA’s umbrella, would be Americans. By declaring land on Mars to be theirs, they would, in effect, be preventing any other terrestrial nation from using and controlling that land. Musk himself has already openly proclaimed his disdain for international treaties governing Mars. In a recent speech in Philadelphia, he declared, “We should not have any sort of international treaties that restrict the freedom of Americans.”

Even if he intends to create a nation on Mars that is independent of the United States, in practical terms this is likely to be impossible. People on Mars will be completely dependent on resupply ships sent from Earth, which will come from the United States. Indeed, as President Trump put it in his inauguration address, “We will pursue our manifest destiny into the stars, launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars.”

If a Starship carrying potential Martian settlers launches from the US, and these settlers explicitly plan to create a new nation in space, the US will be in violation of the OST treaty. How will other countries react to such an explicit treaty violation, which may lead them to lose access to key resources on Mars? Will they view this as simply the first step towards violating the related terrestrial agreements regarding Antarctica and Deep Ocean exploration? In short, will Musk’s space colony be the first step to undermining an international agreement that has helped maintain peace on Earth for over a half a century?

The likelihood that we will actually have to face this dangerous and destabilising possibility is small, because for now, Musk’s dreams remain more science fiction than science. But if the US allows its space exploration plans to be hijacked to support Musk’s visions, the result will be a tremendous waste of resources. It will lead to misplaced US national priorities in science and technological development and undermine international peace and cooperation. The downsides are tremendous, then, yet it is not clear what—if any—benefits would arise from rushing to accommodate the illusory dreams of one man, even if he is immensely rich and powerful.

.png)