Why is America finding it so hard to return to the Moon? Sixty years ago the nation managed the task brilliantly, going from simple loops around the Earth to a fully fledged lunar landing in under a decade. Now they seem to be struggling to get off the ground. Despite pouring tens of billions of dollars and more than two decades into the effort, another lunar landing looks as far off as ever.

Except perhaps it doesn’t. America’s politicians now seem to fear a rival could beat them to the lunar surface. China has been rapidly building up its capacities in space. It has a space station in orbit, has landed multiple probes on our natural satellite, and is fast constructing a giant new Moon rocket. A Chinese landing could come by the early 2030s.

Officially, this is not a problem. According to NASA’s public schedule, America will launch Artemis II early next year. This will send a crewed capsule around the Moon, putting astronauts within touching distance of the surface. In 2027, that will be followed by Artemis III, and in this flight astronauts will actually land, take some selfies and collect some rocks, and then head back home.

Sadly, no one believes this will really happen. Even if Artemis II flies as planned – which seems plausible, given the rocket has now been stacked and is moving closer to actually launching – Artemis III certainly won’t. NASA has no working lunar lander, it has no spacesuits for the crew to wear on the surface, and it has no realistic way of getting any of that ready by 2027.

The reasons for this inevitable failure are myriad. But perhaps the clearest is simple bad management. While the NASA of the 1960s could move relatively fast and fly scrappy missions to test concepts, the NASA of the 2020s cannot. It must serve Congress, and it must support thousands of jobs scattered across America.

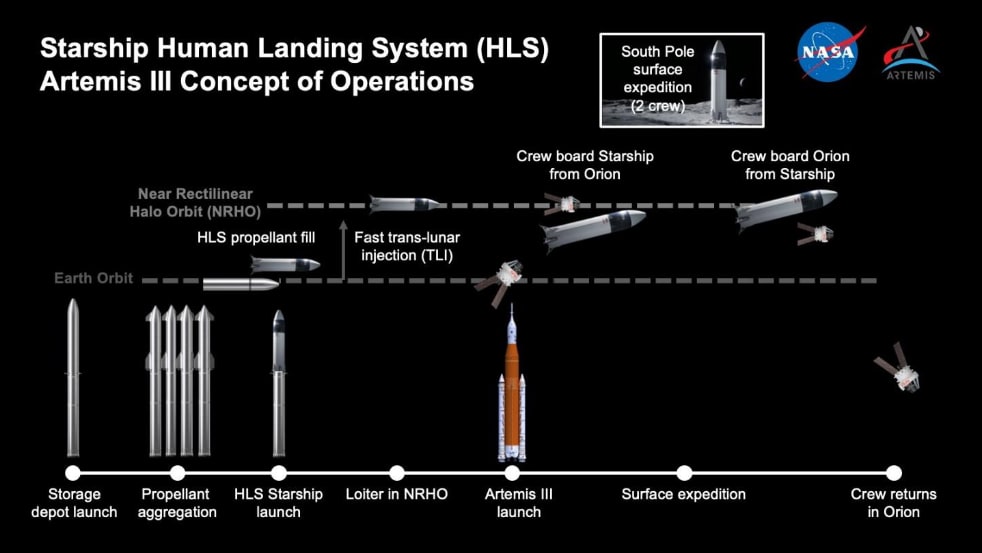

That has resulted in a terrible overall architecture. Artemis depends on a rocket that costs four billion dollars to launch, and that only manages to loft about half as much mass as the Saturn V of the 1960s could. It uses a capsule with known flaws in its heat shield, but which NASA will anyway fly on the next mission. And it relies on a lander that is comically oversized and requires the support of a dozen Starship launches simply to fuel it up.

So what to do? At this point there are few good options to ensure a landing by the end of the decade. Although some people have suggested alternative architectures, all of them need a lunar lander, and one simply hasn’t been built yet. NASA could stick with the current plan – which is to hope SpaceX get Starship working and prove it can land on the Moon.

Or they could, as Acting Administrator Sean Duffy said in October, ask someone else to build a lander. Perhaps. But the odds that anyone can do this by 2030 are low. Time now is simply too short, and the problems with Artemis are too great. China – barring unknown setbacks with their program – may well put the next footprints on the Moon.

America should instead look to build a more sustainable human spaceflight programme. The next decade will bring the end of the International Space Station and an increasing Chinese presence in space. Who gets to the Moon next doesn’t really matter. What follows does, and what they build and do then is where the real victor will be determined.

On November 2, the International Space Station marked twenty-five full years of human occupation. In that time, almost three hundred people have visited the facility, staying for periods ranging from a few days to a whole year.

That is worth celebrating. Few objects in space manage to last that long, and nothing else is as big or as complicated as the space station. As a piece of engineering it is certainly a wonder of humanity, a showpiece of the early twenty-first century.

Yet its days are numbered. The station was not designed to last this long, and in places it is clearly showing its age. Some of its modules are cracking, and its air is constantly escaping into the vacuum around it. One day it might fail catastrophically, forcing its occupants to flee. But even if not, its main sponsors, America and Russia, want to pull funding within the next decade.

Officially, its demise is set for 2032. SpaceX is building a special vehicle to bring it down then, using a controlled – if still somewhat risky – manoeuvre that will plunge it into the depths of the Pacific Ocean. But of course, that date may still be postponed: as long as the station is habitable, and neither Russia nor the United States have a good alternative, an incentive remains to keep it running.

What might such an alternative look like? For Russia, the Chinese station, Tiangong, might be a good option. Though smaller than the International Space Station, it is much younger and already home to crews of astronauts. So far, all have come from China – but the country’s space agency has said that foreigners are welcome. Russia might well take that opportunity.

But for America things seem less clear. NASA has no plans to fund a full replacement to the current station. That would probably be fantastically expensive – the current one cost more than one hundred billion dollars – and the agency is currently occupied with an attempt to send people back to the Moon.

Instead, NASA is hoping private enterprise will step in. A handful of companies have expressed interest. Among them is Axiom, a company that has sent its own astronauts to the ISS and that plans to attach its own module to the station in the coming years. And there is Vast, a start-up that hopes to use SpaceX to launch its own station in May next year.

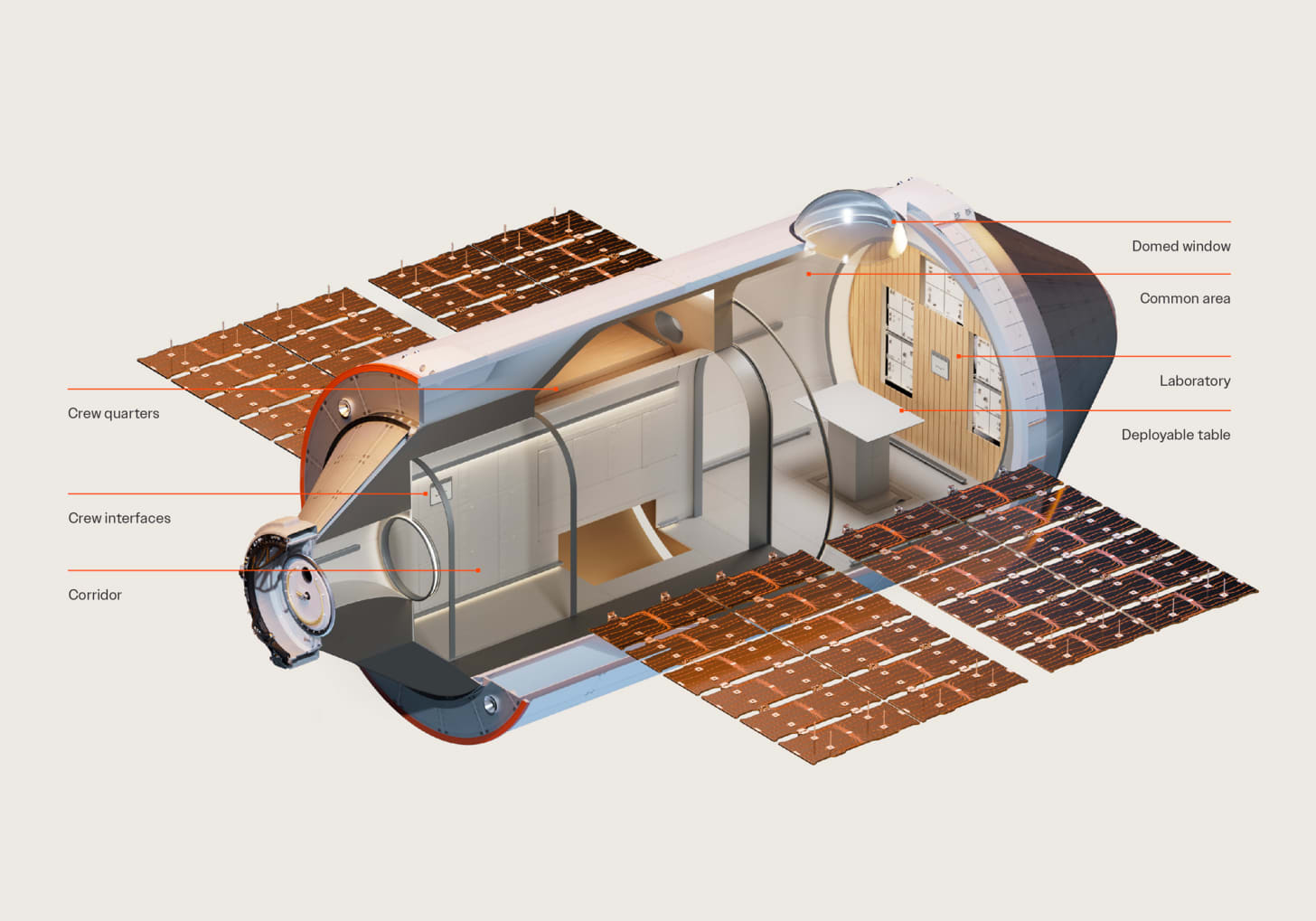

Haven-1, as they call it, will be a small-scale demonstration. In size it is little more than a large room, and though Vast has created some beautifully styled renderings of the planned spacecraft, it is not hard to see its limitations. Nevertheless, the company hopes to send four crews on short visits over three years.

Last week, Vast made a big step towards this goal by launching Haven Demo, a pathfinding mission that seeks to demonstrate the technology needed to keep its future station stable. If they can do this, and they can find the money to build a full-scale station, then America may well have a small but still functional outpost in orbit for decades to come.

On October 29, the interstellar comet 3I/Atlas reached its closest point to the Sun. It is now heading outwards, flying away from our star and speeding back towards interstellar space. Unfortunately, however, the comet is also passing behind the Sun as seen from Earth, and is thus hard to observe.

Luckily, it is still in view of some of our solar telescopes, which have been watching the comet for some weeks now. Their early reports – and these are sadly limited by the ongoing shutdown of the American government – suggest 3I/Atlas suddenly became much brighter as it approached the Sun.

The reasons why are not yet clear. Yet Avi Loeb points to this, alongside other oddities like its bluer-than-expected colour and an apparent unexplained shift in its trajectory, as evidence of some unseen engine at work. Loeb, of course, thought the comet, or alien spaceship, would use this opportunity to make a sudden manoeuvre towards Earth. That, as far as we can tell, has not happened.

3I/Atlas is anyway drawing closer to Earth. Though it is unlikely to become bright enough to be seen by human eyes, it will become more easily visible to our telescopes. On December 19th it will make its closest approach to our planet. After that, the time for observations will be short. By early next year it will be gone, lost once more among the vast and empty darkness of outer space.

Japan’s space agency announced the official end of the Akatsuki mission to Venus. Though contact was lost with the probe more than a year ago, operators had continued efforts to restore communications until September of this year. But then, given the age of the spacecraft and the length of time without contact, they decided to stop trying.

Akatsuki was launched in May 2010. It was supposed to enter orbit around Venus later that year, but a fault with its propulsion system meant the planned burn failed. Fortunately, a second opportunity came in 2015, when operators were able to use an alternative set of thrusters to steer it into orbit.

From then on, Akatsuki was devoted to studying the climate and clouds of our twin planet. It sent back some incredible pictures of Venus, and revealed new details of how its clouds move and the impact of mountain ranges and other surface features on its atmosphere.

The demise of Akatsuki means there are now no active missions operating around Venus. Nor is any likely to arrive soon. Despite the proximity of Venus, only the European Space Agency currently has clear plans to send another probe– EnVision – though even this will not arrive until the 2030s.

Why Not Venus?

When most people talk about sending people beyond Earth, they have one of two destinations in mind. The first is the Moon, which is lovely and all, but really a very boring place. The other is Mars, which is just about close enough for a crew to reach, rocky enough for them to land on, and with a great deal of effort might be habitable enough for them to survive on.

.png)