Weizmann Institute of Science researchers say that they can identify individuals based solely on their nasal breathing patterns with 96.8% accuracy.

The groundbreaking study found that these nasal respiratory “fingerprints” are so unique that they can provide identification of individuals as successfully as voice recognition.

The scientists said they uncovered the close relationship between the brain and breath, offering insights into people’s physical and mental health, including their body mass index, depression, and anxiety.

“Are we depressed and therefore breathe differently, or do we breathe in a certain way that makes us feel depressed?” asked PhD student Timna Soroka, a member of the Olfaction Research Group, in an email to The Times of Israel.

Soroka said the study shows that if it is true that people breathe in a way that leads to depression, “then this opens the door to new interventions and treatments based on breath.”

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

x

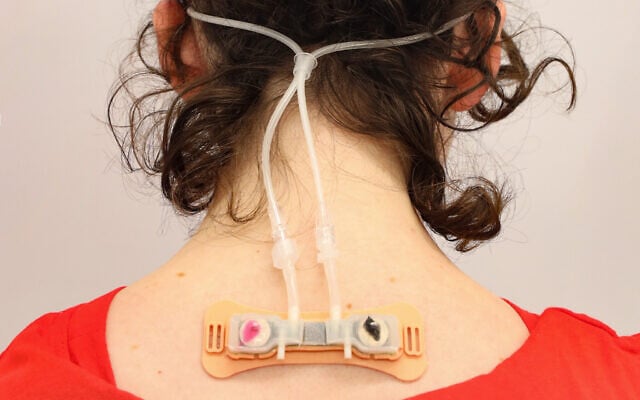

A wearable device to track nasal airflow continuously has been developed by Weizmann Institute scientists. (Ofer Perl/Weizmann Institute)

The link between breath and brain

The focus of the scientists at the Olfaction Research Group is to explore the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the sense of smell, known as olfactory processing, and how this sensory perception affects human health and behavior.

In mammals, the brain processes odor information during inhalation. This link between the brain and breathing led the researchers to wonder: Since every brain is unique, wouldn’t each person’s breathing pattern reflect that?

Weizmann Institute of Science PhD student Timna Soroka with the breathing device (Ohad Herches, Weizmann Institute of Science)

“You would think that breathing has been measured and analyzed in every way,” said Sobel, but they wanted to explore the hypothesis that breathing patterns may identify an individual.

Most breathing tests last between 1 and 20 minutes, focusing on evaluating lung function or diagnosing diseases. The researchers believed that those brief “snapshots” weren’t enough to capture the subtle patterns of breathing, so they developed a lightweight wearable device that tracks nasal airflow continuously for 24 hours using soft tubes placed in the nostrils.

“As far as we know,” said Soroka, “we developed a new way to study respiration. Not over short durations, but rather as a long-term time series.”

Sobel’s team fitted the device on 100 young adults — all of whom met diagnostic criteria for mental and behavioral health– and asked them to go about their daily lives.

Using the collected data, the team identified individuals based on their breathing patterns with high accuracy, even after almost two years.

The accuracy rivaled some voice recognition technologies.

“I thought it would be really hard to identify someone because everyone is doing different things, like running, studying, or resting,” said Soroka. “But it turns out their breathing patterns were remarkably distinct.”

The scientists had hypothesized that they would be able to identify a person by their breath, but Soroka said, “We were surprised by how strong the effect was.”

Illustrative image: a doctor in a clinic checks a patient’s breathing (Prostock-Studio via iStock by Getty Images)

What our breaths reveal

The study also found that the individual patterns of breathing correlated with their state of mind.

Participants who scored relatively higher on anxiety questionnaires, for example, had shorter inhales and the pauses between breaths during their sleep time were more variable.

“This suggests that long-term nasal airflow monitoring may serve as a window into physical and emotional well-being,” the researchers said.

They are investigating whether people can mimic healthy breathing patterns to improve their mental and emotional states.

“We definitely want to go beyond diagnostics to treatment, and we are cautiously optimistic,” Sobel said.

In 2024, the researchers published a study that found that nasal inhalations in Parkinson’s patients were longer and less variable than in healthy individuals. The difference enabled them to accurately determine most people who had Parkinson’s disease and how severe their disease was.

They believe that future studies will determine whether breathing can contribute to the early diagnosis of Parkinson’s and other health conditions.

“We stumbled upon a completely new way to look at respiration,” said Sobel. “We consider this a brain readout.”

.png)