The IBM Personal Computer was launched on 12 August 1981. Designed by an IBM team in Boca Raton, Florida led by Philip Don Estridge and William C. Lowe.

That first PC, given the less than charismatic designation as the ‘Model 5150’, and its successors quickly set the standard for personal computing, first in business and then in homes. So much so that they became known as just ‘PCs’.

But the PC was never an true ‘IBMer’, the colloquial term used for IBM employees.

Wait a moment! The IBM PC. Designed and manufactured by IBM. With IBM on the badge on the front of the machine. Surely it was an IBMer!

Well, there are two levels on which the PC wasn’t really a true IBM machine. The first is well known and fairly obvious, the second more subtle.

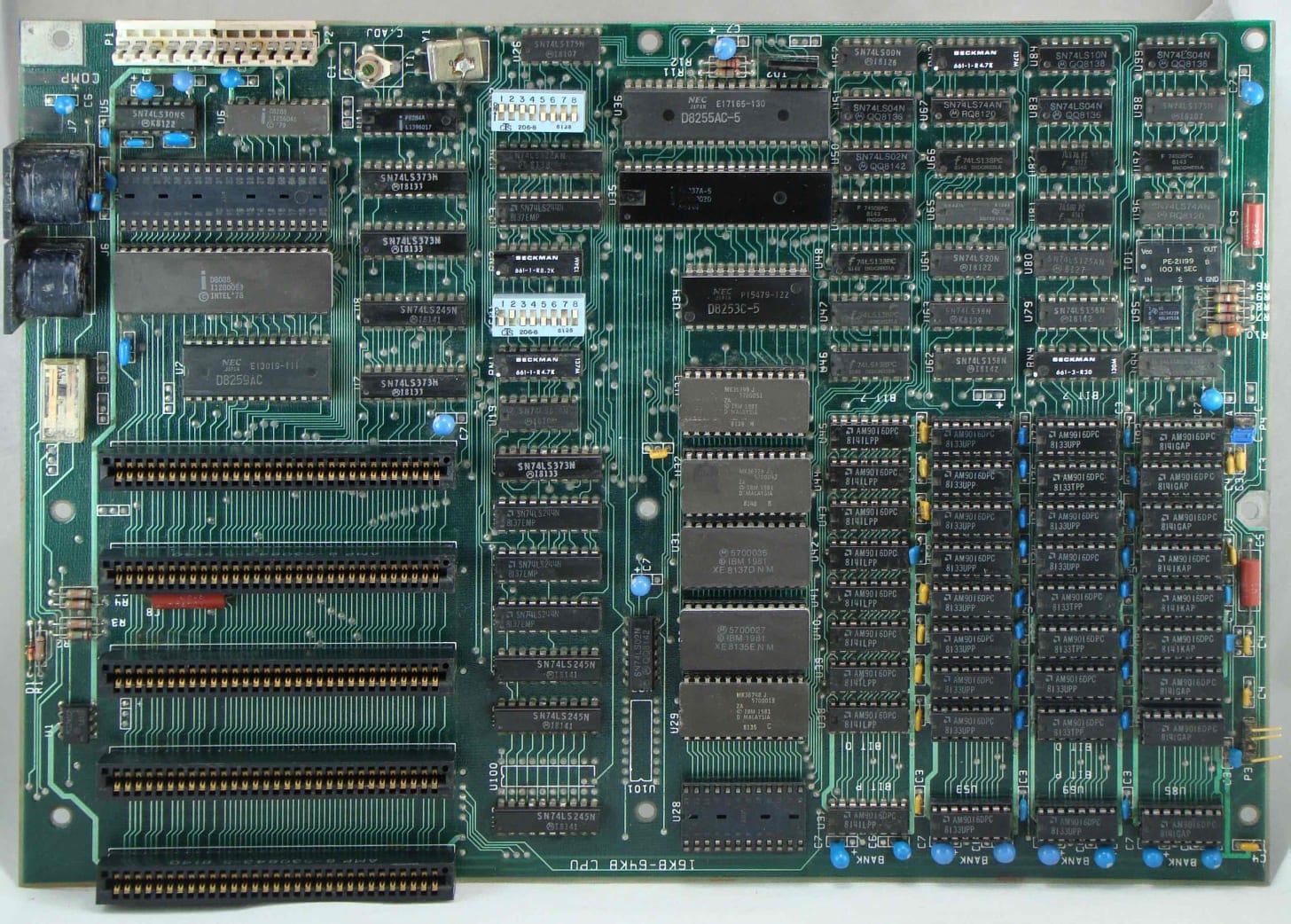

First, the IBM PC was created by assembling components from other manufacturers. Crucially, CPU was from Intel (the 8088) and the operating system (PC-DOS) from Microsoft. The PC ecosystem would later be build on the ‘WinTel’ partnership, but in the early days it was ‘DOSTel’.

Then, the crucial software ecosystem that soon gave the PC it’s insurmountable moat was made up of non-IBM products. First Lotus 1-2-3, Wordperfect, dBase II and then later Microsoft’s own Office suite.

What did IBM bring to the PC? The Basic Input and Output System (BIOS) that provided the interface to the underlying hardware was written by IBM. IBM’s own factories assembled the machines. But most crucially for the success of the PC, though, IBM brought the quality of it’s support and it’s endorsement as a personal computer that was worthy of ‘serious’ businesses.

In many ways that first IBM PC was the successor to the Apple II as the most open and expandable machine on the market. Steve Jobs hated the PC, but, of course, the Apple II was really Woz’s computer and its values reflected Woz’s own. Jobs’s ideal machine was the more refined but closed Macintosh.

IBM had most of the capabilities to make key components of the PC itself. Yet the approach of using external suppliers was entirely rational. IBM had already had a few attempts at making ‘personal computers’ and they were often innovative and impressive efforts. The IBM 5100 for example from 1975 was a portable that was several years ahead of its time.

None of these efforts stuck and the closed nature of these machines was part of the problem. The much more open 5150 was more familiar and accessible for both software and hardware developers.

As Steve Jobs explained in 1996 …

The IBM's first product was terrible. It was really bad and we made a mistake of not realizing that a lot of other people had a very strong vested interest in helping IBM make it better. So, if it had just been up to IBM, they would have crashed and burned. But IBM did have, I think, a genius in their approach, which was to have a lot of other people have a vested interest in their success. And that's what saved them in the end.

Except those other people didn’t really have a vested interest in IBM’s success.

IBM’s Annual Report for 1984 has an interesting front cover. Central amongst the boxes with software lined up at the back, are Microsoft’s PC-DOS and BASIC. Products that would form the basis for Microsoft’s coming rise and the wide availability of which would lead to IBM’s fall in the PC market.

Because IBM’s BIOS was soon reverse engineered. Assembling PCs could be done more efficiently by others. And with IBM as underpinning the market, highly credible competitors, such as Compaq, soon emerged, offering better value and more advanced products.

IBM had no moat around the PC. IBM steadily lost market share before selling the PC business to Lenovo in 2005 for a paltry $1.3bn.

In less than a year Lenovo was distancing itself from the illustrious IBM brand:

Since Lenovo took over the personal computer business on May 1, 2005, the company's advertising and marketing efforts have excluded IBM almost entirely. The four television spots that Lenovo ran during the Turin Winter Olympics, for example, never mentioned IBM at all.

Source New York Times in April 2006

Being an ‘IBM’ PC just didn’t mean that much any more. It was just another beige box along with machines from Dell, HP and many more.

And there is another reason why the dependence on external components was bad for IBM: it had little or no control over the PC as a product.

The major updates to the PC came with new components from suppliers. The first big upgrade to the PC came with the Intel 80286, Intel’s successor to the 8088/6 series of processors. IBM had little or no control over the timing or nature of this upgrade.

IBM was an major Intel shareholder in the 1980s, owning more than 20% of the chip-maker at one point. IBM insisted that it was granted a second source license that allowed it to make x86 processors and IBM did make processors under this license. One such was the IBM 386SLC (known as the "Super Little Chip") used in some IBM PS/2’s. IBM failed to take much advantage of this license though.

Then, IBM tried to take control of the PC market with the PS/2 which had much more proprietary IBM technology and was designed to be ‘clone-resistant’. The role of the IBM PS/2 in this story deserves a whole post of its own. In short, it was too late, and IBM’s attempt to regain control of the PC market and ecosystem would, after some initial success, fail completely.

Which brings us to our second, more subtle, reason why the IBM PC wasn’t really a true IBM machine, one of which I have personal experience.

My first real job was as an ‘IBMer’. In 1984 I worked as a lowly junior employee in a remote outpost of the IBM empire. I worked in a small marketing support team responsible for producing material for the PC and IBM’s smallest minicomputers.

IBM was awash with cash. The PC was enormously successful and everyone knew it. IBM’s global headquarters in Armonk imposed restrictions (such as headcount) on our bit of the business, but spending money was never a problem.

IBM was selling mainframes, minicomputers and now PCs, along with an ever changing line-up peripherals and other machines, now mostly forgotten. It was a complex business!

With it’s global footprint and relationships with almost every type of business, from multinationals to local businesses with just a few employees, this presented a huge managerial challenge. More specifically, how did IBM’s management ensure the correct balance between effort to sell each of these products?

One of the tools was a series of targets based on points allocated for sales of particular products. One that has remained with me was ‘NPII’ (pronounced ‘nippy’). I have no recollection of what NPII stood for (please excuse this oversight, IBM had hundreds of acronyms, and it was a long time ago) nor is there any trace of it online. I do remember that it was a system of points allocated for sales of software. There were a lot of these acronym-shortened measures covering every aspect of IBM’s business. You only got your bonus if you met your ‘software NPII’ targets.

It was with these tools that IBM’s senior management sought to direct effort to sales of products that really mattered. And here’s the thing: I can recall no enthusiasm for selling the PC amongst my fellow IBMers. It sometimes seemed like they would rather you bought a single ‘real’ IBM product such as a System/36 Mini than a hundred PCs. Was it those sales targets, cultural resistance or something else? I don’t know, but somehow the PC, successful as it was never seemed to be a priority.

There may have been good reasons for this. Maybe the margins on PC sales were so poor that this made sense (I doubt this was the case in 1984, but it’s possible). Maybe those who ran the minicomputer business didn’t want to be disrupted. Or maybe, right at the top of IBM, they realised that there was no moat around the PC (an insightful and intellectually honest position, but again probably unlikely).

Which is not to say that IBM ‘rejected’ the PC internally in any sense. PCs were absolutely everywhere inside IBM.

IBMer’s loved the PC: they just didn’t seem to want to prioritise selling them.

IBM did interesting things with the PC. There was the PC XT/370 for example which created a mainframe compatible machine in a PC box. But there were never any real synergies with the rest of IBM’s business.

The first reaction when IBM entered the PC market was one of shock. IBM took everyone by surprise by making a machine that was much more ‘personal computer’ than IBM. It was open in two senses: first, it had taken some of the best components available in the market; and then it had created a machine that was open to both hardware and software developers. It was an immediate and overwhelming success.

Did that ‘openness’ doom IBM in the PC market from outset, as is the conventional wisdom? Was it inevitable that an attack of the clones would lead to IBM’s eventual exit?

I don’t think so, for two interlinked reasons.

First, IBM didn’t make the most of its dominance. It did little to make the IBM version of the PC truly unique.

Second, I don’t think that culturally IBM ever really felt that the PC was a true IBM product. The ‘antibodies’ of IBM’s immune system suppressed it.

We now know that the Mac survived as an Apple product, but IBM abandoned the PC. Intel prospered and Intel powered servers ate much of IBM’s lunch.

History takes strange twists though and today a very different IBM is valued at twice the market value of Intel.

And mention of Intel makes me wonder about all the products that Intel has tried to launch to enter new markets: Atom in smartphone, various AI accelerators, GPUs and so on. Were these all suppressed by Intel’s own corporate immune system?

.png)

![Every Image You've Ever Seen Can Come from This [video]](https://news.najib.digital/site/assets/img/broken.gif)