To borrow a quip from Mark Twain, the reports of Universal Basic Income’s death have been greatly exaggerated. This essay serves as my response as a subject-matter expert in this particular field to recent shots fired against cash transfers like this liberal one and this conservative one. For over ten years, I’ve been reading and compiling the results of basic income pilots and unconditional cash studies. I can assure you that the authors of such think-pieces, however evidence-informed they may appear to be, are akin to the blind-folded touching an elephant’s trunk and claiming they’ve discovered a new species of snake. They know more than nothing, but they don’t know enough to know how much they don’t know.

Here’s 9 things you need to know about recent unconditional cash transfer experiments:

COVID-19 happened: For pilots that distributed monthly cash between 2020 and 2023, the pandemic, stimulus, and high inflation need to be considered as potential confounds by comparing to pilots that happened outside those years.

The U is universal: Part of what makes UBI a UBI is universality. A non-universal pilot can help inform the discussion, but not as much as a universal pilot that uses a saturation site design can.

The household size problem: Part of what makes UBI a UBI is also that every member of a household gets the money. If a household of four gets $500 a month, that will have less of an impact than one person getting the same amount.

Prevention versus treatment: It’s one thing to provide cash to those in need. It’s another to provide cash to prevent need.

Time is a factor: Fewer strong conclusions can be drawn from a one-year experiment or even a three-year experiment than from decades of data.

The control group problem: Control group details vary from experiment to experiment. Consider this carefully.

Evidence for thee but not for me: Those who may wish to provide benefits-in-kind vs. cash tend to not care about benchmarking those programs against cash.

Missing the forest for the trees: Concluding that targeted cash is better than UBI is missing the point of how effective UBI is at actually reaching those in need.

There’s more to poverty than brainwaves: It would be very interesting if it turns out that UBI can impact brain development, but if it doesn’t, so what?

It feels like Covid, which is still around and infecting people mind you, up and got memory-holed. For those who have forgotten, a new coronavirus kind of went and infected the entire world in 2020 which caused all kinds of problems besides the hospitalizations and deaths it caused. It was an extremely stressful time. My own personal experience was spending ten days in the hospital at the bedside of my wife as she fought it before there were any vaccines to help. Stressful is an understatement.

One of the things being claimed recently is that basic income experiments have shown surprisingly little impact on mental health, and this is from pilots like Sam Altman’s OpenReseach (ORUS) pilot that provided $1,000/mo starting in 2020 and ending in 2023, and the Baby’s First Years (BFY) experiment that started in 2018 and provided money for a child’s first 4 years and 4 months. The researchers themselves have included in their studies that it’s likely that the pandemic served as a confounding variable, but the people writing think-pieces about this stuff seem to be just hand-waving that away.

Here’s how I like to think of this: Imagine that we just invented the lifeboat and we decided to put it to the test in the open ocean to see if it would save lives. We go out to sea, put our boat in the water and then—bam!—a super typhoon happens and the lifeboat sinks. Would it be fair to conclude from our test that lifeboats don’t work?

This is what seems to have happened with cash instead of lifeboats. It turns out that apparently $333-$1,000 of monthly unconditional cash per household may not be enough to overcome the massive stress and macroeconomic impacts of a global pandemic. Does that mean UBI doesn’t work? Well, maybe, but before we draw that conclusion, maybe we should look at experiments before and after the super typhoon.

What I find particularly interesting in this regard is the Stockton pilot that started providing $500/mo in February 2019, a solid year before Covid hit. The results from the first year showed significant improvements in mental health, comparable to medication. Then Covid hit and the second year results showed that over the course of the study, there was no significant improvement. This seems to indicate that the stress of the pandemic just overwhelmed the cash.

In fact, Baby’s First Years also followed this pattern. The year-one analysis used only data prior to the pandemic, and those results showed that infants in the $333/mo group showed more power in high-frequency bands which is consistent with increased cognitive development. Unfortunately, only 435 of the 1,000 kids were able to be tested before the pandemic hit, so the sample was 43.5% of the size it should have been, and thus too underpowered to draw any strong conclusions.

However, there’s a pile of other studies to learn from about the mental health impacts of unconditional cash. The biggest one I know of is one from Brazil that used the “100 Million Brazilian Cohort” which is an absolutely massive dataset. Tens of millions of people received cash from the Bolsa Familia program between 2004 and 2015, and it turns out that suicide risk was reduced by 61%. Clearly, that kind of massive cohort and duration makes a strong case for mental health improvements via cash.

A systematic review was published in 2021, the first of its kind, that looked at observational studies of social security policy changes in high-income countries and summarized the mental health effects of those policies. 38 studies were included in their review. 21 looked at increases in social security and 17 looked at decreases in social security. They found that overall, “policies that improve social security benefit eligibility/generosity are associated with improvements in mental health,” and that ”social security policies that reduce eligibility/generosity were related to worse mental health.” More income security = good. Less income security = bad.

Those are real-world policy results from high-income countries based on far more than three studies, over a period of time far greater than three years, based on getting cash to far more than a thousand people. That’s what actually happened when people had increases or decreases in their economic security due to government policy reforms outside of a pandemic.

Additional confounds beyond the pandemic but directly related to it are the stimulus we did to combat its economic impacts, and also the period of high inflation that followed. Both of those are important to consider.

For example, take a household of two parents and two kids in a control group. It’s possible that both parents lost their jobs, and got paid $800 a week each in 2020. Maybe that was actually an increase in pay for them, so they went as a household from $3,200 a month to $6,400 a month. That family also got three stimulus checks, totaling $11,400. They also got the enhanced child tax credit in 2021 for an additional $600 a month. That’s a big increase in money. If they were part of a pilot looking for impacts of $333, $500, or even $1,000 a month, maybe those amounts were overwhelmed by the rest of the stimulus.

Then inflation happened. From March to September 2022, a family of four was spending about $1,000 more per month in higher prices. Again, it’s possible that an extra $333-$1,000 a month could be overwhelmed by that, with a $500/mo experiment actually looking at the difference between a treatment group with a $500/mo consumption power drop and a control group with a $950/mo consumption power drop. Maybe in such an experiment, both groups are going to see hits to their mental health, and they won’t be significantly different. It’s important to consider that.

All of this is to stress what should be obvious, which is that guaranteed income experiments that occurred between 2020 and 2023 should have an asterisk next to them. It’s not to say there’s nothing to learn from them, but it is to say that confounding variables were present such that their results may very likely have been different had the pandemic not happened.

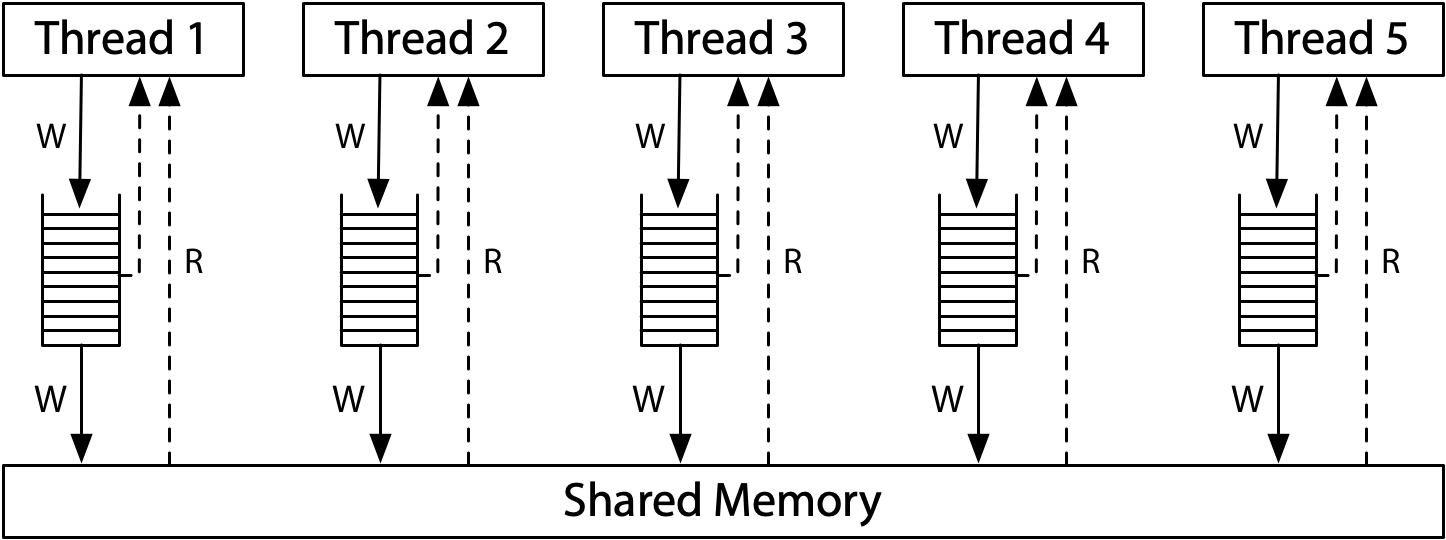

If you provide $1,000 a month to a thousand people across two states with a combined population of 44 million people as ORUS did, that’s not a universal basic income. UBI would be if all 44 million people got the money. If you give one person $1,000 a month, that will help that person to some degree, but it won’t help anyone else, which in turn limits its potential for the individual, because they’re the only ones spending it.

Consider a town with a population of 5,000 people where five people get $1,000 a month in unconditional income. Also consider a second town that is identical, where all 5,000 people get $1,000 a month. Do you think it’s possible or even likely that five people in the second town who are identical to the five people in the first town will have a different experience?

We already know the answer to this is yes. Alaska has been providing money universally to everyone every year since 1982. One of the many studies of it looked at employment impacts and found that there was an overall increase in employment. The increase was due to the spending of the money, which created additional jobs for unemployed people to take. If only a thousand people in Alaska got that money every year, the spending of that money would not spur any employers to hire anyone new.

So when we look at a pilot like the ORUS pilot that provided $1,000 a month to 1,000 people spread out across Illinois and Texas and find an average decrease of 8 days a year (or 15 minutes a workday) in paid work, we also have to consider the possibility that people who wanted a job simply couldn’t find one. And they may have found a job if everyone around them also had additional money to spend that would have created new jobs to find.

A properly designed universal basic income experiment involves a “saturation site” where an entire community gets the money. It could be a village or a town, or a part of a city, but the treatment group needs to test the impacts of universality in some way. Experiments like this have been carried out. The Namibia UBI experiment provided money to an entire village of about 1,000 people. The India UBI experiment provided money to eight entire villages, which was about 6,000 people. The Dauphin experiment in Canada in the 1970s used a saturation design, providing income to a third of the population of Dauphin, which had a population of about 10,000 people. All three of these experiments had very significant positive results.

Namibia observed a 301% increase in entrepreneurship and a 42% decrease in all crime. Employment increased 25%, school attendance doubled, and dropout rates fell from 40% to 5%. India observed a tripling in entrepreneurship, more employment overall, and better health. Dauphin observed a 9% decrease in hospitalization rates, a 15% fall in crime, and a 37% fall in violent crime that was mostly due to far less domestic abuse. A more recent saturation pilot at the community level in India even resulted in the community forming a new labor union.

The closest thing to a saturation pilot in recent years among the 150+ guaranteed income pilots in the US took place in Chelsea, MA, during the height of the pandemic, when about 15% of its population via lottery of 40,000 people experienced a guaranteed $200 to $400 a month per household depending on household size. A randomized controlled study of its impact on health found a 27% decrease in emergency department visits compared to the control group. The largest decreases were behavioral health–related emergency department visits, which dropped 62% relative to the control mean, and substance use–related emergency department visits which dropped by 87%.

Those health impacts are so large that I wonder if the pandemic may have functioned as a confound in the opposite direction, where outside of a pandemic, perhaps the money would have had less of an impact, but it makes no sense to ignore such results in defense of an opinion that claims a UBI in the US would have no health impacts, while holding up some non-saturation pilot to defend the opinion.

From all the studies I’ve read, it appears that the biggest impacts from cash provision appear within saturation pilots where entire communities benefit universally. Remember that the next time you hear that a basic income pilot was somehow disappointing. Was it a saturation pilot?

The federal poverty line scales by household size, because the more people there are in a home, the more money is needed to meet basic needs. Right now, for one person in 2025, it’s $15,650 with each additional person adding $5,500. A household of five thus needs $3,138 a month to not live in poverty, using FPL guidelines.

Most of the pilots going on in the US have involved giving money to one person in a household. This can still tell us useful stuff, but it needs to be kept in mind that UBI scales by household size. If one adult in a household of four gets money, that’s not simulating a universal basic income. If all four do, or at least all adults, then that’s simulating a universal basic income.

Besides the already mentioned Chelsea Eats program that provided $200/mo for a household of one, $300/mo for a household of two, and $400/mo for a household of three or more, and Alaska’s annual UBI that provides the same amount to every member of a household, and the 2021 enhanced child tax credit that provided money for every child in a household, there’s no data to point to in the US about money that scales by household size.

Now consider again the Baby’s First Years pilot that people are uplifting as evidence against UBI. That was $333/mo for a minimum of two people. That same amount went to moms with two kids, and three kids, and four kids, and more. According to interviews as part of that study, the largest household size was ten people. The median household size was five.

It’s possible that this could be a factor in the BFY study results so far, especially when combined with other confounding variables like the pandemic, and how stimulus payments and the CTC went to all kids. Perhaps $333/mo for a household of five just isn’t enough to move the needle for cognitive development, and if the study had only looked at single moms, the researchers would be finding significant results. It’s possible.

Researchers in Germany considered this possibility in their unconditional basic income study design, so what they did was provide 1,200 euros per month for three years to only single adult households. This enabled them to have a better understanding of what that amount of UBI would do for an individual. What they found was a third of a standard deviation improvement in mental health. To put that in perspective, medication usually helps a bit less than that, and therapy can help as much or a bit more than that. This finding also agrees with the Stockton pilot prior to the pandemic that also found a medication-equivalent impact on mental health.

So when someone is upholding the ORUS results as showing no impact on mental health, besides that pilot being impacted by the pandemic, it also only provided $1,000/mo to households and the mean household size was 3 people. Using FPL guidelines, the poverty line for a household of three is $26,650. That’s $2,221/mo. It’s possible that $1,000/mo for three people is simply too small based on household sizes just as the $333/mo BFY study may have been. This is what the German experiment points to as likely considering the very significant mental health results they found, and what the Chelsea study that scaled by household size also found.

Another of the arguments people have been making lately is that unconditional cash is most effective in certain situations and not in others, and so cash should be targeted to those specific situations, like for example getting money to women during pregnancy, or right after someone is released from incarceration, or right after a disaster happens, etc.

One of the biggest benefits of a universal basic income in practice is that it’s already flowing to people at their time of need. No need to fill out any forms or prove anything. No need to wait and cross your fingers that your request will be approved. The money is already there and more is coming soon according to a set schedule.

It’s certainly interesting to test something like the Denver Basic Income Project did, which was to see if basic income could help get homeless people housed faster. The results of that experiment are among those considered “disappointing” by not revealing a large difference between those provided $50/mo and $1,000/mo. For the record, 45% of people who were homeless at the start were no longer homeless ten months later compared to 25% of those given $50/mo. I don’t consider that disappointing. I also don’t consider it disappointing that the selling of blood plasma dropped 60% for those given $1,000/mo and went up by 17% for those provided $50/mo. But let’s assume for a moment that giving homeless people money doesn’t help them at all.

Helping people avoid becoming homeless is extremely helpful, and has been shown to save more than it costs. A large study in Chicago of around 5,000 people found that getting them a payment of around $1,000 right when they needed it reduced their chances of becoming homeless by 88% in the following three months and 76% in the following six months.

We have an entire safety net built around treating poverty instead of preventing it, and that approach is needlessly expensive. Child poverty alone costs us over $1.5 trillion a year. We could see a 15x return by investing in lifting all kids out of poverty. We also know from the SSI program (that currently provides a max of $967/mo) what the impact is of kicking people off of SSI. A 1996 reform created two equivalent populations that could be studied. One group kept getting SSI at age 18 and the other group didn’t. A 2022 study of those groups found that the loss of SSI resulted in a 60% increased chance of ending up incarcerated, eliminating the savings of spending less on SSI. A 2021 study estimated the cost of crime in the US to be over $2.6 trillion a year. We also spend over $5 trillion a year on healthcare treating illness.

One of the best studies of the health impacts of basic income has been going on in North Carolina since 1996 when a quarter of the kids in an ongoing study of poverty started getting biannual dividends as Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian (EBCI) tribe members. After twenty years, researchers found that those who have received the basic income and continue to receive it use less alcohol and fewer drugs, commit fewer crimes, and are more likely to graduate from high school. Teen pregnancies are also less common among them, and their average IQ is a bit higher. They are also half as likely to experience depression as non-recipients, and a third as likely to experience high anxiety. Economists have compared the total amount of money to the savings in expenditures on crime and medical care and found that by age 26, benefits exceeded the amount of cash distributed by a factor of three to one.

Also very interestingly, the strongest benefit of the cash occurred in the children of families who received the transfers for the longest duration and who received a larger transfer due to having two Native American parents (scaling by HH size). This supports the hypothesis that a higher amount of basic income has more health and crime impacts than a lower amount, and that the longer someone has a basic income, the better those impacts will be.

This brings us to the next important factor to consider.

A study of basic income that lasts one year is interesting. A study that lasts two or three years is more interesting, especially if it isn’t confounded by a pandemic, but a study that spans a decade or two or three or more is far more interesting. I’ve already covered some of what we know from decades of basic income. The Alaska dividend gives us over 40 years of data to examine. The EBCI dividend covers almost 30 years of data and continues to this day. It’s now distributing over $15,000 a year. The 1996 SSI reform also resulted in 30 years of data.

From what I can tell having studied hundreds of cash studies, the positive results build over time, and the biggest impacts are from getting basic income to kids before they are born and never removing it. The impacts on these kids as adults are as clear as day and unimpeachable. To hold up a 3-year study done during a pandemic to argue that basic income is disappointing while entirely ignoring decades of data is methodological malpractice. It cherry-picks a short, shock-ridden window and calls it truth. The longitudinal evidence draws a clear picture and if your conclusion needs to erase the long-run record to survive, your conclusion is wrong.

As Annie Lowrey included in her response piece in The Atlantic, “the second- and third-order effects [of cash transfers] take time to show up in the data.” She added, “mothers’ pensions, the precedent for today’s welfare program, had muted effects on the women receiving them from the 1910s to the 1930s, but significant effects on the lifetime earnings and educational attainment of their sons, decades later.” She didn’t go into that further but I will, because I found them fascinating too when I first learned about them.

The Mothers’ Pension program was our first government welfare program in the US and it provided cash to moms. It averaged about $500/mo to $750/mo in today’s dollars during the decades it ran. A 2014 study of it found that male children of accepted applicants lived one year longer than those of rejected mothers and received one-third more years of schooling, were less likely to be underweight, and had 14% higher income in adulthood than children of rejected mothers. Imagine canceling that program four years into it in the belief that the cash just wasn’t working. It would have negatively changed the life trajectories of tens of thousands of people.

We also have four decades of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) which provides cash to tens of millions of families near the poverty line. From all those years of data we know that “an additional $1,000 in EITC exposure when a child is 13 to 18 years old increases the likelihood of completing high school (1.3%), completing college (4.2%), being employed as a young adult (1 %), and earnings by 2.2%.” A 2021 study of the EITC found that a 10 percentage point increase of it led to 4% fewer suicide attempts and 1% fewer deaths by suicide. A 2022 study found that it reduced the alcohol abuse of pregnant mothers. EITC money also improves birthweights, which happens to also be an observed result of the Alaska dividend too.

Please note that none of this is to say there is nothing to learn from 1-3 year studies of unconditional income. One of the interesting findings from the experiments we did in the 1970s came from the cohort in the Seattle and Denver negative income tax pilots that were told they would get the money for 20 years but only got it for 9 before the money was canceled. Their results didn’t differ from the 3-year or 5-year findings. So depending on what you’re measuring you may get the same results short-term as long-term, but long-term findings that disagree with short-term findings, I believe carry more weight in terms of being applicable to UBI discussions.

One of the surprising findings from the Denver Basic Income experiment that provided unconditional income to homeless people was how well the control group did that got $50 a month. What isn’t ever pointed out in any of the opinion pieces that use the results in their arguments against universal basic income is the possibility that the $50 provided on a regular monthly basis to those experiencing the greatest amount of desperation actually had a significant impact on its own, but we can’t know for sure because there was no group that received $0 a month.

The $50/mo group also didn’t only get cash. They became part of a community that cared about them and connected them to resources. They were all given phones with free service. Many of them also received welfare benefits like SNAP and SSI that were additional for them but lost by those given $1,000 a month. Compare someone getting $1,000 and losing $967 in SSI to someone with $967 in SSI provided an additional $50. That’s not +$1,000 vs +$50 but +$33 versus +$50. It’s not really a test of $1,000 compared to nothing. In this example, the person provided $1,000 is actually $17 worse off than the one provided $50.

This is an unfortunate problem with many of the guaranteed income pilots that have gone on and continue to go on in the US, and is something that Mother Jones covered well this year. The federal government and many state governments do not make it easy to study basic income. There’s a lot of state-by-state variance, such that some states don’t count basic income towards programs like SNAP and Medicaid, but SSI is always withdrawn as income increases and if your income is $1,000/mo, you get $0 in SSI thanks to SSI considering basic income as unearned income. If it were considered earned income, it would be reduced by 50 cents per dollar instead of a dollar per dollar.

The Finland experiment even had a similar kind of problem that the experimenters themselves complained about from the beginning, which was how many of the participants kept getting other welfare benefits that exceeded the amount of the basic income (€560/mo), which they would have lost by becoming employed, so even though Finland still saw a small employment increase, it likely wasn’t as large as it otherwise would have been had none of the participants been in the situation of losing other larger benefits for their family upon accepting a job.

From the qualitative report, we know it was also not uncommon for those in the $50/mo group in Denver to express feeling more security due to the money, and also a positive feeling of being trusted, which improved their well-being. And some of them also believed that they would get $1,000/mo when the experiment ended, pointing to the possibility of survey responses that were rosier than they would have otherwise been. This is a somewhat similar problem to the 1970s experiments where the design of the experiments created an incentive for people to say they earned less than they actually did, in order to get a larger amount of money, because the amount scaled by income during those experiments.

There’s also always the problem of attrition in control groups. When it comes to an experiment involving homeless people in particular, this can mean half the control group not responding, only leaving those who got housed, which can make the control group look like it did better than if it were able to get data from everyone in the control group. In the Denver pilot, the control attrition rate was 38%, meaning that only 62% of the control group remained in the data.

It’s important to keep all of this in mind when there’s a null finding from a cash study that found no significant differences between the control group and treatment group. The question must be asked, was the control group truly a control group in the sense of what we usually think of as a control group, where it was virtually identical to the treatment group except for the cash?

One of the most frustrating things for me personally is how much evidence there needs to be in support of unconditional cash. In just this article alone, I’ve pointed to many more than the three studies that naysayers are currently holding up against UBI, and where the results weren’t even negative, but simply null. A null finding can be interesting and we can learn from it, but it’s still not a negative finding. Where are the piles of studies that were done in advance of other safety net programs? Where are the experiments that tested to make sure a new middle-class tax credit worked, or a new tax cut for the rich worked? Where are the RCTs that benchmark benefits-in-kind against cash that are demanded before a new non-cash benefit?

For over a decade now, I’ve been compiling study after study as a thread on Twitter/X and now Bluesky. Here’s a dynamically-updated page that makes it easy to go through everything I’ve compiled. Go look at it sometime, because I can’t put it all here. Spend some real time going through it all. You’ll find far more than the results of three experiments cherry-picked for some anti-UBI op-ed.

As a prime example, the results of a first-of-its-kind study were just released that actually put housing vouchers to the test. It was the first ever RCT experiment to test vouchers against cash, and it took place in Philadelphia. Researchers very cleverly took advantage of the long wait lists for housing vouchers to just start giving cash to those waiting. It’s a four-year test that will continue until Summer 2026. The median amount of money recipients are getting is $881 per month. Try guessing what the results were halfway through.

Ready?

Two years in, one out of four housing voucher recipients were not able to use their housing vouchers anywhere, and those who were able to find someone to accept their voucher took about four months to find that housing (additional note: only 1 in 4 who qualify for housing vouchers ever even get them). At the 18-month mark, the vouchers had reduced homelessness by a statistically significant 19% compared to the control group (who only got a small amount of money every six months for each survey and who had no attrition issues). Meanwhile, 100% of the unconditional cash group were able to use their cash for housing, because it was cash, and were able to use it in just 3 weeks instead of 4 months, and saw a drop in homelessness compared to the control group of a statistically significant 67% at 18 months.

The unconditional cash was therefore almost four times as effective as the housing vouchers at reducing homelessness at 18 months. This is a hugely impressive finding. I was one of those listening live as the results were released, and I wasn’t alone in being surprised by the difference in effectiveness. We assume so much about our existing safety net. Virtually none of it has ever been RCT-tested against cash, and yet here we are, testing cash again and again and again.

Did you read about these voucher versus cash results in The Argument? No? Did you read about them in a New York Times op-ed by David Brooks? No? Why not?

In regards to cash versus non-cash benefits, there’s something economists refer to as the marginal value of public funds (MVPF) that measures the efficiency of government spending. If the government spends $1 on a program, the MVPF asks: how much do people actually value that $1, after accounting for costs and side effects? Cash transfers usually have an MVPF close to or above 1.0, because people can spend the money on whatever they need most. Housing vouchers are 0.7, meaning they have about 70% of the value to people as cash. For SNAP it’s 0.61. For job training it’s 0.44. The programs with the highest values of between 2 and 5 are programs for kids’ education and healthcare. (Note: hat tip to Matt Darling on responding with these stats)

So we actually already know that for many of our programs, people would prefer just being given cash instead, and when we do an RCT comparing a non-cash benefit to cash, we find cash does better, but here we are still arguing over cash? Why? Because the reason we don’t have UBI yet, is not because we lack evidence. It’s because we don’t really care about evidence.

You may hear the argument that unconditional cash does work just fine actually, but only in certain circumstances, for certain people, at certain times, in certain places, and certainly not for people who don’t need it, where “need” is very vaguely defined but accepted to certainly not include Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates. In a world of god-like bureaucrats, this may actually make sense. With god-like powers, we really could target people with aid right when they need it, and we would have a god-like definition of “need” where we help people who most wouldn’t define as being in need, but who actually are in need. We’d be gods, anything would be possible. It helps to be all-knowing when delivering unconditional cash assistance.

But we aren’t all-knowing. We aren’t gods. Constant universality is how to actually reach all those people that gods would, because we would include everyone all the time. And because we can all agree that billionaires aren’t in need of any help, we can just tax billionaires far more than the amount of any UBI they would be provided. We can raise taxes on those in the entire top 10% more than the amount of UBI they receive, so that they get the UBI just like everyone else, but pay it back and more via taxes. In a world without gods, universal provision is the best way of reaching everyone you want to reach, and taxation is the best way of reverse-targeting those you feel aren’t in need.

Because cash is simply what most people prefer in many cases outside of education and healthcare, do cash. No need to spend on vouchers that people wish were just cash, who would sell their vouchers for cash at a loss if they could. No need to pay all the middle-men to do all the testing to determine who needs what, and in so doing, watch people fail those tests, or corruptly take a cut, or result in people refusing to even apply or feel the lesser because of what being in need and accepting help says about them. Targeting creates stigma and stigma means helping fewer people than if there were no stigma.

If an experiment shows a null result, such that there’s no difference between conditional benefits-in-kind and unconditional cash, then why are we doing conditional benefits-in-kind? Why is the cash seen as a failure? If we can do cash without work requirements and the impact is the same as cash with work requirements, then why are we doing all the bureaucracy to make sure people are working? We know work requirements don’t increase work, and dropping them doesn’t decrease work, and can even increase it, so what are we doing? Why are we wasting money on all the bureaucracy?

When it comes to universality, besides making sure to reach everyone in need without fail, another benefit is not discouraging anyone from increasing their income. Targeting means withdrawal rates which mean high marginal tax rates. SNAP has a marginal 30% tax rate such that every dollar earned means losing 30 cents of SNAP. Housing vouchers also have a 30% marginal tax rate. SSI has a 50% rate on earned income (100% on unearned income) such that a dollar gained is 50 cents lost. These combine, so if someone with SNAP, SSI, and a housing voucher increases their income by a dollar, they lose $1.10. They are ten cents worse off for working. Does that make sense to you? That’s a ceiling built over the heads of those with disabilities, basically locking them into an existence where they aren’t allowed to earn any money.

The testing we do to make sure people have low income actively encourages people to keep their income low. UBI doesn’t do that. With UBI, everyone is always better off increasing their incomes. None of the US experiments are testing marginal tax rate differences. Spain did. Spain’s experiment found that cash with a 100% marginal tax rate decreased work (big surprise). They also found that cash with a marginal tax rate of 25% to 35% increased work.

When the pandemic happened, we got people money, but the $600/week bump to unemployment we provided was conditional on remaining unemployed. We literally paid people to not work. That makes sense within the context of a pandemic, but not outside of one. And in normal times, besides imposing a 100% marginal tax rate, unemployment income also only reaches 28% of the unemployed. UBI would reach 100% of the unemployed and apply a marginal tax rate of the bottom tax bracket’s 10%.

Also during the pandemic, we provided stimulus payments to most people, which was great, but we did it based on incomes from 2018 and 2019. There were people with low incomes in 2020 who got no stimulus payment in 2020 because of old data that showed them with high incomes. Again, that is a reason for universality plus taxes as income-testing after the fact.

I mention all of this to try and get everyone to look at the big picture that extends far outside of any one unconditional cash experiment. The question of going with universal basic income extends far beyond a null result from a few-years-long experiment focused on a specific group. It’s about the dignity we extend to that group and everyone else, and the realities of actually reaching them and others in need, and the labor market distortions of the targeting we do, and the resources we waste on all the hoops we make people jump through like trained seals.

Unconditional beats conditional. Universal beats targeting. Cash often beats non-cash. Per person beats per household. All of these things we already know point right at UBI as the way to go.

The final point I want to make is in response to the notion that unconditional cash doesn’t work because of (insert weirdly specific goalpost here). The Baby’s First Years pilot is such a great example of this because people are actually saying that this study at its 4-year results mark somehow represents a failure of cash in helping kids. Why? Because of a null result on measurements of brain activity using EEG scans.

I’ve already covered why this study just had bad timing with the pandemic, and how its pre-COVID year looked promising, and how household size varied greatly, which can help explain the null results at age 4, but more than that, people are being really weird about this study in claiming it shows cash doesn’t help kids. The experiment itself was very interesting. Because of known correlations between parent income and child brain activity, maybe lack of money is actually causing kids’ brains to develop differently. This study was meant to help figure out if lack of income caused less brain development. If the findings at 4 years had found significant results in this regard, that would have been intriguing. But not finding it isn’t some kind of F-grade for cash.

I’ve already covered just how much evidence we have to show that unconditional income is extremely helpful for kids in all kinds of ways, and how different results can be observed later on in life. We already know this stuff. We just don’t know yet about early brain development and unfortunately because of the pandemic, even this experiment won’t settle that question. But there is no question about the effectiveness of cash in reducing poverty and helping kids grow up to be higher functioning adults who become more educated, earn more, abuse substances less, do less crime, and live healthier, longer lives.

In fact, research has already established a bidirectional causal relationship between poverty and mental illness. We know that loss of income can cause mental illness. We also know that cash transfers reduce mental illness. We know that losing income can worsen mental health and lead to even less income which can lead to even worse mental health. These are RCTs telling us this.

Universal basic income can break this feedback cycle by always being there for everyone as a floor below which no one can fall, that also functions as a solid foundation to help everyone build upon.

Poverty is a state of being that most of us will move through in our lives — more than half of us actually. 50% to 60% of Americans will live in poverty for one year before they are age 75. That’s not because 3 out of 5 people get lazy for a year. It’s because stuff just happens. If you don’t have a college education, your odds are 75%. If you do, your odds are 50%. If you’re Black, your odds are 84%, and if you’re white, your odds are 54%. These are the result of systems, not individuals.

We want to believe that poverty won’t happen to us, because we make good decisions, and that poverty happens to those who make bad decisions. But it just doesn’t work that way. During the pandemic, the unemployment rate spiked to 15% within 8 weeks. We don’t know what impacts AI is going to have, but one recent NSF-funded report suggested 25% job displacement by 2028.

We temporarily changed the way we helped each other during the pandemic because it was easier to see hardship wasn’t deserved in that context. We need to come to see all hardship within that context, and maybe hardship caused by AI will help us in that regard as COVID did.

Mexico recently reduced their overall poverty rate by a whopping 26% in just 6 years. They did that by tripling their minimum wage and providing unconditional cash to everyone over age 65 every two months. That was just a political decision they decided to make to reduce poverty. It didn’t happen because 26% of Mexico started making better decisions.

By teaching us to view poverty as a moral failure of the individual, society keeps us from realizing that poverty is actually an ethical failure of society itself. We can write all the op-eds for the New York Times we want, and it won’t change the fact that we could choose to help each other more, and trust each other more, and extend more dignity to each other, and we just don’t.

We create more than enough food for everyone to eat, but we waste 40% of what we produce. We have more than enough ability and resources to house everyone, and we just don’t. We don’t do these things, not because a scientific experiment showed us what we do right now is what’s best. We do it, because it’s just how it’s been done.

Poverty is a legal status based on an income measurement. Someone experiences poverty because their income is too low, often because they lost their job, or had a kid, or got too old, or became disabled. This then has a range of effects on that person that includes greater stress which can lead to substance abuse and then homelessness. It leads to the survival anxiety of fight or flight that in turn can lead to poor health, crime, and violence against strangers but also loved ones. It’s a downward spiral we can prevent with cash and services. It really just comes down to the choice of seeing others more like we see ourselves—as having inherent worth.

Don’t be fooled by the weakly-informed opinions of people who don’t want things to change or only want things to change in a way that they themselves don’t insist upon a mountain of supporting evidence in order to support while ignoring literally hundreds of studies that disprove their views.

UBI’s obituary writers are leaning on a few pandemic-tainted, non-saturation, household-misaligned pilots and calling that a verdict. It isn’t. When cash is tested under conditions that actually map to UBI—per person, community-wide, for long enough, with clean controls and benefit-interaction designs—the pattern is clear: basic income cuts poverty and its collateral damage, improves health and education, reduces crime, and supports work through boosted demand and bargaining power. Cash also clears the basic efficiency test. If an in-kind or conditional program cannot outperform unconditional cash in a fair head-to-head RCT, it does not justify its frictions, cliffs, and cost.

Poverty is an income deficit, not a character deficit. Close the income deficit with a universal floor and reverse-target the top through taxes. That reaches the people that targeting misses, removes punitive marginal tax traps, and replaces administrative suspicion with simple rules that compound benefits over time. The nulls pulled from a once-in-a-century shock tell you about that window of time, not about the general case. Alaska’s UBI, the EBCI’s UBI, the CTC and EITC, saturation pilots, large-N transfer research and so much more tells you about the general case.

If the problem is too little money and stability (which it is) give people money monthly and stop charging them for proving it. And also stop charging people for increasing their incomes. The big question is not whether cash “works,” but whether anything else works better at comparable scale and cost. Until shown otherwise, choose the mechanism with the highest demonstrated value to recipients alongside education and healthcare. That’s unconditional basic income.

UBI is not a theory in search of proof; it’s a foundation in search of political will.

If you support my UBI work, please share this post and click the subscribe button. Also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my work.

Special thanks to my monthly supporters on Patreon: Gisele Huff, Steven Grimm, Haroon Mokhtarzada, Bob Weishaar, Judith Bliss, Lowell Aronoff, Tricia Garrett, David Ruark, Katie Moussouris, Jessica Chew, Larry Cohen, Daryl Smith, A.W.R., John Steinberger, Albert Wenger, Mgmguy, Joanna Zarach, Robert Collins, Tom Cooper, Dylan Hirsch-Shell, Laurel gillespie, Frederick Weber, Liya Brook, Philip Rosedale, David Ihnen, Peter T Knight, Michael Finney, Andrew Yang, Arjun , Natalie Foster, Joe Ballou, Albert Daniel Brockman, Walter Schaerer, Elizabeth Corker, Miki Phagan, Steve Roth, Stephen Castro-Starkey, Deanna McHugh, Braden Ferrin , centuryfalcon64, Leslie Kausch, Juro Antal, Mark Broadgate, Chuck Cordes, Jason Clark, Mark Donovan, Jocelyn Hockings, S, Felix Ling, '@Justin_Dart , Tommy Caruso, and all my other patrons for their support.

Thanks for reading Foreword to Civilization! This post is public so feel free to share it.

.png)