The Successful Ego, of course, raises itself above others on its ‘special’ achievements. Football manager, José Mourinho, enraged egos everywhere by saying:

‘Please don’t call me arrogant, but I’m European champion and I think I’m a special one.’ (Richard Morgan, ‘Special One: Remembering José Mourinho’s first-ever Chelsea press conference’, Sky Sports, 18 October 2018)

Sports journalists have never forgiven Mourinho for this comment and love to remind him and us of it every time he’s sacked by a club: ‘Is Mourinho still “the special one”?’ The journalistic ego deeply resents being a mere commentator on the lives of ‘stars’ hogging the limelight, just as editors and publishers resent being ‘mere’ facilitators of their authors’ work.

While the Suffering Ego raises itself up on its own ‘special’ problems, the Righteous Ego’s ‘specialness’ lies in its unusual concern for the problems of others. The comedy series, Seinfeld, loved to nail this form of pride. After an uncharacteristically selfless act of generosity, Jerry thinks to himself:

‘I am such a great guy! Who else would’ve gone through the trouble of helping this poor immigrant? I am special. My mother was right.’ (Seinfeld, The Café, 6 November 1991)

Torben Betts has been described as ‘An uncommonly gifted playwright’ (Time Out) and ‘a political Beckett’. In his 2012 play, Muswell Hill, Betts’ character, Julian, is a fine example of a Righteous Ego. Julian’s widow, Karen, reveals that her tormented husband had committed suicide by throwing himself off the cliff at Beachy Head:

‘Sometimes he could be a right moody old sod, but I understood him, you see… Because he was such a strict vegetarian, he ended up despising all meat eaters and because he was such a committed cyclist he hated all motorists. And he’d get so wound up by people’s indifference and stupidity that he used to be so full of … well, hatred.’ (Torben Betts, Muswell Hill, Oberon Books, 2012, p.59)

It is not a small thing to rail at the lack of compassion in the people around us; it means that they are all morally ‘inferior’. On this basis, our ego will feel entitled to rage, preach and patronise — to assert its dominance over everyone — as brutally as any Successful Ego or Suffering Ego. It ought to be a thing of wonder that so many people ostensibly motivated by compassion for human and animal suffering, are ‘full of … well, hatred’.

The complexity lies in the fact that we can be absolutely right — human beings are often indifferent, the social system is structurally unjust, Western foreign policy is rooted in medieval-style greed and violence, and our egos can hijack being right to justify our own tyrannical abuse.

Others may be wealthier, more famous and beautiful, but the Righteous Ego can slip the surly bonds of ‘ordinariness’ and ascend to the moral ‘high ground’. If we have a political argument with someone we perceive as more conventionally successful (a parent, for example), our Righteous Ego may fight tooth and nail to establish our ‘superiority’ in at least this ‘ethical’ dimension.

In short, if the billionaire’s Successful Ego feels ‘superior’ because it has more financial credit, the Righteous Ego feels ‘superior’ because it has more moral credit.

Small gestures will do. Having spent decades working for a climate-killing oil company, or an international bank, we can point to our vegan diet, our meticulous recycling, or the fact that we read the supposedly left-liberal The Guardian newspaper as proof that we are nevertheless more ‘ethical’ than others. The flimsier the support for the Righteous Ego, the more fiercely that support will be defended. Even polite, rational questioning of the health benefits of veganism, or the left credentials of The Guardian, may set the fur flying.

A key problem is that the extreme, domineering behaviour of a Righteous Ego can easily be mistaken for extreme compassion — they’re angry, impatient and abusive because they care so much. In reality, predatory individuals and organisations have always understood that they can hide their crimes behind a screen of fake compassion. British readers will recall how, for 20 years, the BBC’s serial child rapist and abuser, Jimmy Savile, presented a TV programme ostensibly dedicated to fulfilling the dreams of children: ‘Jim’ll Fix It’. Tony Blair, who oversaw the Iraq oil grab costing at least one million Iraqi lives, made much of his party’s ‘ethical foreign policy’. The Italian philosopher, Machiavelli, wrote:

‘It is not essential … that a Prince should have all the good qualities which I have enumerated above, but it is most essential that he should seem to have them … Thus, it is well to seem merciful, faithful, humane, religious and upright, and also to be so; but the mind should remain so balanced that were it needful to be so, you should be able and know how to change to the contrary.’ (Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, 1513, Dover publications, 1992, p.46, my emphasis)

The crucial word here, repeated twice: seem. What looks like concern may just be cover for a domineering ego. This frequently becomes obvious when The Righteous Ego is offered a choice between remaining ‘merciful, faithful, humane’ and winning ‘mainstream success’.

‘You Think It’s Funny Turning Rebellion Into Money?’

Righteous Egos pursuing political change, for example, are highly vulnerable to the temptation of transitioning to more standard Successful Egos. Time and again, I have seen young, idealistic writers start out on radical websites, only to succumb to the lure, not just of joining the ‘mainstream’ corporate press, but of doing so by self-censoring and compromising their message. I’ve seen wonderfully unique, clear-thinking voices mangled by their struggle to sew with a double-pointed needle — telling the truth while being accepted, embraced and rewarded by a heavily filtered media system.

We see this tendency throughout modern culture. Consider The Clash, one of the fiercest anti-establishment, anti-capitalist bands of the punk era. Their song, London Calling (1979) was an apocalyptic call to arms. The title mocked the BBC World Service’s tradition of beginning its reports ‘This is London calling…’, much as the Sex Pistols’ song, God Save The Queen, mocked the UK’s (then) de facto national anthem. The website Songfacts says of London Calling:

‘It was the song that best defined The Clash, who were known for lashing out against injustice and rebelling against the establishment, which is pretty much what punk rock was all about.’

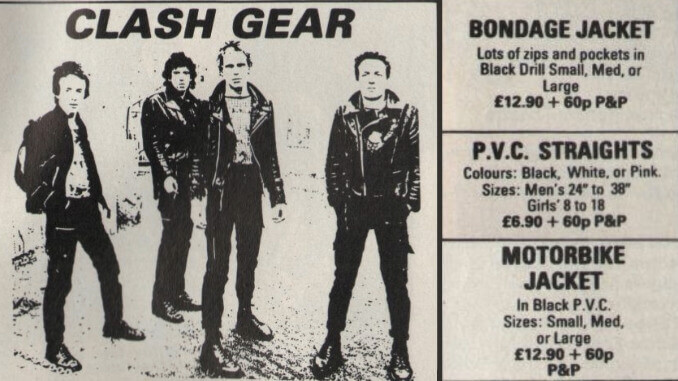

In photo shoots, The Clash were often depicted as a menacing, grim-faced street gang in black leather jackets, Doc Martin boots and ‘bondage’ trousers (music magazines used to sell this ‘Clash gear’ to fans). The call from London was for popular insurrection:

‘London calling to the faraway towns, now that war is declared and battle come down.’

In the early 1990s, The Clash resisted a request from British Telecom to use London Calling in an advert. But by 2002, singer-songwriter Joe Strummer had sold the rights to the song to luxury car manufacturer Jaguar for use in an advert. Strummer explained:

‘Yeah. I agreed to that. We get hundreds of requests for that and turn ’em all down. But I just thought Jaguar … yeah. If you’re in a group and you make it together, then everybody deserves something. Especially twenty-odd years after the fact. It just seems churlish for a writer to refuse to have their music used on an advert…’ (Mark Vallen, ‘London Calling – Selling out the legacy of Punk’, Art For A Change)

‘Churlish’ or not, in the 1978 Clash hit, (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais, Strummer had sung:

‘The new groups are not concerned

With what there is to be learned.

They got Burton suits.

Ha, you think it’s funny

Turning rebellion into money?’

London Calling was used in an advert for the Jaguar X-Type — ‘a sleek four-door aimed at the “entry-level luxury” segment and retailing for a relatively modest $30,000’. (Rob Walker, ‘Brand new Jag — The Clash sell luxury goods’, The Boston Globe, 15 September 2002)

The song was later used in a 2012 British Airways advert and in the James Bond movie Die Another Day. At one point, Strummer actually worked as a DJ for the BBC World Service on a programme called ‘Joe Strummer’s London Calling’. After the band broke up, another Clash song, Should I Stay Or Should I Go, made it to number 1 in the UK, heavily assisted by its inclusion in a Levi jeans advert. The Boston Globe commented:

‘By now you could make a pretty good compilation of subversive music that’s been used in ads, with selections from Lou Reed (Perfect Day in a spot for the NFL), Iggy Pop (both Lust for Life in a Carnival Cruises ad, and the Stooges song Search & Destroy in a Nike commercial for the 1996 Olympics), the Ramones (Bud Light once used Blitzkrieg Bop), the Buzzcocks (Toyota), and even Creedence Clearwater Revival’s scathing indictment of America’s privileged class, Fortunate Son (repurposed by Wrangler) … The famously lefty British band Chumbawumba sold the rights to the song Pass It Along … to Pontiac, and then turned their earnings over to a progressive activist network.’

The Sex Pistols were a major inspiration for The Clash. Tragicomically, the Pistols’ singer, Johnny Rotten, later dressed up as a country squire in a commercial selling Country Life butter.

David Edwards is co-editor of medialens.org and author of ‘A Short Book About Ego… and the Remedy of Meditation’, Mantra Books, available here. He is also the author of the forthcoming science fiction novel, ‘The Man With No Face’, to be published by Roundfire Books in 2026. Email: [email protected]

This is the second extract from ‘A Short Book About Ego’, the first was published last month here. An interview with J.J. Stenhouse on UK Health Radio is available here.

Some Comments About ‘A Short Book About Ego’

‘In this compelling short guide for the head-trapped, David Edwards shows us how meditation has the power to bring each of us a healing, personal bliss by dissolving our insatiable egos. But he offers a powerful, bigger message too: a politics anchored in the love and compassion released by meditation is the only effective path to healing our broken societies.’ (Jonathan Cook, winner of the Martha Gellhorn special award for journalism, author of ‘Israel and the Clash of Civilizations’)

‘I have learnt a great deal reading A Short Book About Ego, a thoughtful and gentle book about the change of consciousness we all need to go through. I read it just after reading the Bhagavad Gita while travelling through northern Pakistan, which gave me extra context.’ (Peter Oborne, award-winning journalist and broadcaster, author of ‘The Fate of Abraham: Why the West Is Wrong About Islam’)

‘The best way to transcend the ego is to understand it. This book shines a bright light on the machinations of the ego, and shows us a glimpse of freedom beyond it. Best of all, it highlights the clearest path to freedom, through the practice of meditation.’ (Steve Taylor, author of ‘The Leap’ and ‘Extraordinary Awakenings’)

.png)