Below is the final installment of my three-part story on Hunter Thompson. Here are the links to part one and part two.

This is part of an ongoing series of essays on counterculture figures—including (so far) Jack Kerouac, Frank Zappa, Bob Dylan, Joan Didion, Eden Ahbez, and Gregory Bateson.

By Ted Gioia

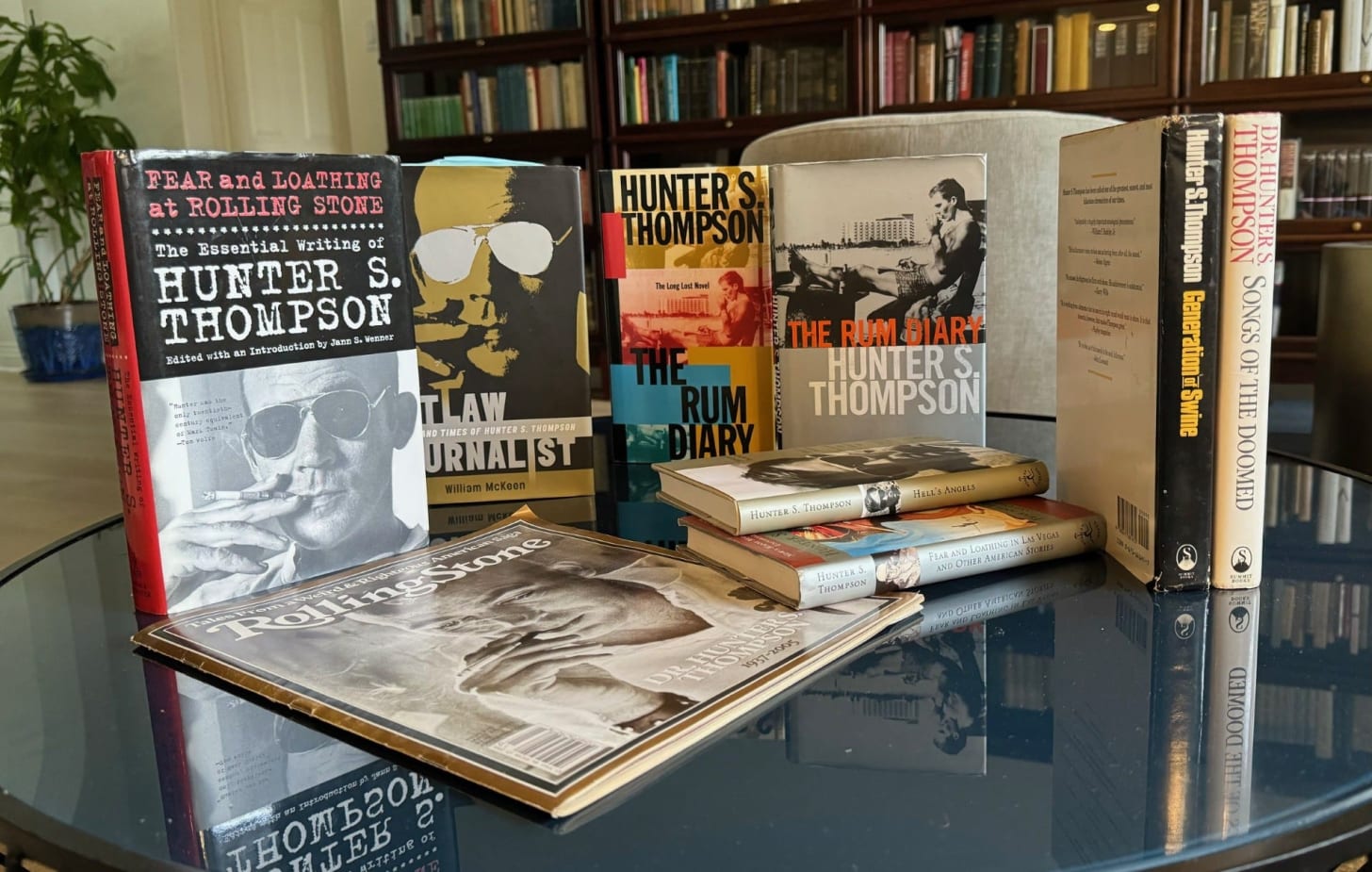

No writer in the long history of Rolling Stone has ever been as famous or fêted or feared as Hunter S. Thompson. The magazine discovered its own mojo in the Gonzo creed and its many adherents. But all this came at a terrible price.

Rolling Stone boss Jann Wenner bragged about his ability to edit—and motivate—his eccentric freelancer. “I think I was the best editor around for him,” he later explained. “I understood the balance of when we had to work and to play and indulge him. Hunter wanted to find an editor he could be in fine hands with. . . . He knew I would do that always.”

But dealing with such an unpredictable force was a demanding chore. Thompson submitted brilliant pages and paragraphs—often over the fax machine late at night—but they were never sequential or chronological the way stories are supposed to be. The first page out of the fax (or Mojo Wire, as Thompson called it) might be labeled “Insert K” and the editor would have to figure out what the hell to do with it.

Thompson himself often couldn’t answer that question.

So, in his urgent need to meet a deadline, Dr. T. often submitted his best scenes and paragraphs, still uncertain how to stitch it all together. In the heat of the moment, editors were forced to make these decisions—which was especially difficult in those early days of telecommunications, when the Mojo Wire might skip or blur a key line in the text.

This process took a toll on even the most stoic stoners at Rolling Stone. And don’t underestimate the financial costs involved. Thompson believed that every purchase contributing to his fear and loathing should be reimbursed by his employers—so his expense reports included drugs, alcohol, weapons, and other unconventional tools of the journalistic trade.

And even if Jann Wenner was pleased, other parties were less forgiving—and often left holding the proverbial bag. Thompson was so tough on credit card companies that he eventually got banned for life by American Express, and put on a quasi-blacklist by others purveyors of plastic. And for every bill in default, there were still others he avoided completely, leaving them abandoned at the scenes of his various crimes.

If pushed, Thompson would defend all this rule-breaking. It wasn’t just collateral damage, but a part of his Gonzo craft. In a letter to Jann Wenner, explaining why he refused to make requested changes to the manuscript that eventually became Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Thompson asserted his diva status in no uncertain terms:

“The central problem here is that you’re working overtime to treat this thing as Straight or at least Responsible journalism . . . whereas in truth we are dealing with a classic of irresponsible gibberish. You’d be better off trying to make objective, chronological sense of ‘Highway 61,’ The Ginger Man, ‘Mister Tambourine Man,’ or even Naked Lunch.”

In a moment of Gonzo inspiration (or desperation), Thompson came up with the wild idea that gaping holes in his narrative could be plugged with Ralph Steadman illustrations. From a rational point of view it made no sense at all, but on some zanier cosmic level the notion of fixing craziness by juxtaposing more craziness was brilliant—and emblematic of everything Thompson stood for.

The end result was his greatest work, the one story from Las Vegas that refused to stay in Las Vegas. And the reader’s anxiety that the prose is always on the verge of spinning out into incoherence (what Thompson called his “irresponsible gibberish”) only adds to the overall effect. This tightrope act defined Hunter and his craft and the city he was writing about—like a demented Cirque du Soleil performance in your head.

That’s why Thompson kept coming back to the concepts of fear and loathing in later years. They were, for him, what dialectic was for Hegel or forms for Plato. Those words show up so often in his titles and texts that he probably should have filed a copyright on them.

Even so, many readers see Hunter Thompson differently, without the F&L. For those true believers, he is the greatest free spirit of the 1960s, a walking testimony to self-actualization and defiance of authorities. But Thompson was actually more at home with the disillusionment of the 1970s and after, when dreams of peace and love had withered on the vine. So this should have been Thompson’s greatest period, and it was. . . but only for a short while.

By the time Thompson brought his ragtag journalism act to the campaign trail for the 1972 election, he was as much of a news story himself as a news reporter. That had already been true in his own writing, but now other journalists also saw him as a news-maker, even while he was sitting on the press bus with the rest of them.

“It never occurred to me that so many media people in Washington would know who I was,” Thompson wrote to Wenner on November 18, 1971. He had just gone to a local newsroom trying to cash a check, and ended up getting interviewed for a Q&A. “There’s no escaping it; my history is too public.”

The Washington press corp didn’t actually read Rolling Stone (you couldn’t find it on newsstands in D.C., as Thompson soon learned), but the reporters all knew about him from the biker book or the 1970 Kentucky Derby article for Scanlan’s or some other source. Or maybe they had simply heard rumors and gossip—which eventually brought Thompson mass-market fame among druggies and rebels who never read books of any sort.

The Washington press may also have resented his appearance on the campaign trail, but knew they needed him to add color to their own stories. Thompson, for his part, redefined political reporting in 1972, if only by serving up savage opinions and brutal putdowns that no mainstream journalist would dare put down on paper.

Yet, in some ways, this was already the beginning of the end. In particular, the growing Watergate scandal and eventual resignation of Nixon—which should have served as validation for Thompson’s ‘fear and loathing’ worldview—merely showed up the large holes in his makeshift reporting techniques.

He still found a way to make himself the center of every story—chronicling his drug and alcohol consumption, his struggles to make deadlines, he battles with hotel staff and various petty officials. But the Watergate story was bigger than Hunter’s self-made theatrics, requiring smart investigative reporting and nose-to-the-grindstone effort. Maybe he could have done it back in 1964 or 1965, but it was more than he could muster in the mid-1970s.

It’s ironic that Thompson was actually drinking at the bar in the Watergate the night the historic break-in occurred. In a way, that symbolizes the growing futility of his reportage methods. From this point onward, Thompson was frequently on hand when news stories were about to break, but somehow failed to seize the opportunity.

He traveled to Zaire to cover the famous “Rumble in the Jungle” boxing matchup between Ali and Foreman, but didn’t show up for the actual fight. He journeyed to South Vietnam to report on the end of the war, but left to visit Hong Kong and thus missed the fall of Saigon. He tried covering the 1976 campaign, but gave up after two days in New Hampshire and fled to the comfort of his Colorado farm—although he had known Jimmy Carter for several years, and could have been the perfect chronicler of the election.

And then there was the time Rolling Stone spent thousands of dollars financing Thompson’s stay in New Orleans, with Jimmy Buffett brought along for margarita-esque inspiration. But this too collapsed, never producing the much-anticipated Fear and Loathing at Mardi Gras. Even Wenner must have asked himself: If Thompson can’t cover a party, what story can he handle?

Bill Dixon, who shared lodgings with Thompson during the 1976 Democratic convention, later recalled day after day of over-the-top partying, but never saw Hunter writing or even taking notes. Others had similar stories to share. Perhaps it was the cocaine, as his wife Sandy believed. Or maybe Thompson just didn’t pick the right assignments, but whatever the reason, the Gonzo master was turning into more of a meme or a cultural icon than an actual journalist on the job.

Money went for booze and drugs—and perhaps that was expected when you hired this rebel. And maybe editors would have turned a blind eye to such excesses if a suitable manuscript appeared in the aftermath of the binges. But Thompson failed to launch again and again. More often than not, the Mojo Wire was silent.

By the late 1970s, Thompson’s output was barely one article per year, and then even that proved too much. When he finally agreed to write a piece for Running magazine in 1981, it was his first new journalistic work in three years. But times had changed, and his shtick was a poor match with the new vibe of the Reagan years.

Many readers of Running, a periodical devoted to fitness and healthy living, were outraged at Thompson’s byline in the magazine, and threatened to cancel their subscriptions. Others were angry over the bad words in the article. But for whatever reason, Thompson’s reappearance in print fell far short of a romantic homecoming.

It wasn’t the 1960s anymore, or even early 1970s when Richard Nixon seemed to fire up Thompson’s zeal again and again. Thompson realized this himself, and often spoke about reinventing himself. But there are no second acts in American life, as a great writer once said. And when you’re hellbent on destruction, even surviving the first act is uncertain.

In Thompson’s case, almost everything in his life was in tatters. His marriage to Sandy Conklin (later Sondi Wright) ended in 1980 after almost 17 years. If divorce proceedings were applicable in publishing, he probably would have had a similar breakup with editor Jann Wenner, his other stabilizing relationship—although the two sometimes patched it up in later years. Thompson barely held on to his ties with illustrator Ralph Steadman, who found it harder and harder to live inside the world of fear and loathing, yet also understood how much his own career prospects were linked to his unstable collaborator.

Breakups didn’t solve any problems, at least in terms of the writing. After his marriage ended, Thompson relocated to Key West, Florida (a locale originally named Thompson Island, I note in passing). Here a huge news story arrived literally on his doorstep, when the Cuban refugee crisis dominated the headlines between April and October 1980. He watched his friend Tom Corcoran head off in a boat to cover the story for Newsweek, but the most Thompson could manage was to wave from the dock as his buddy left to photograph the historic boatlift.

Here and elsewhere, Thompson had genuine opportunities to achieve the journalistic reinvention he dreamed about. A hard-hitting story about an international crisis could have started the process, or even led to a Pulitzer. But it was easier just to play the role of public jester, druggie, and gadfly—after all, that’s what most of his fans wanted.

It didn’t help when cartoonist Garry Trudeau created a caricature of Hunter, under the name Uncle Duke, for his popular Doonesbury comic strip—which had an even larger readership than Thompson’s books. Uncle Duke made his first appearance in July 1974, just a few days before Nixon resigned. The timing was uncanny. Just at the moment when the Gonzo King was experiencing intense writer’s block, his cartoon alter ego was showing up in newspapers all over the country.

Thompson seethed over this. “Being a cartoon character in your own time is like having a second head,” he complained. But what could he do? Adding to his anxiety was the plausibility and accuracy of Trudeau’s comic strip parody. The cartoonist seemed to know things at the Thompson residence with such accuracy, one might wonder whether he had inside sources.

There was one silver lining in this cloudy life. Thompson was lucky that his fame alone could now pay the bills, or at least most of them. Colleges offered him kingly sums to give talks on campus, and audiences were delighted—although Thompson showed up without any prepared remarks and just answered questions.

Thompson continued to accept writing assignments—especially if they involved a free trip to a desirable destination. But he rarely delivered the goods, and when new work did get published it almost always involved outside assistance: constant handholding, extreme editing, or even outright thievery and deception.

For Thompson’s book on Hawaii, The Curse of Lono, the author never actually delivered a manuscript. Instead, editor Alan Rinzler came to his home and stole rough drafts and notes after Thompson passed out. “I waited for Hunter to fall asleep and I gathered up all the manuscript, including parts of it that were hand-written on shopping bags and napkins.”

The resulting book was poorly received. Even Rinzler admitted that “it was a patchwork, a cut-and-paste job. It doesn’t quite make sense.” But if you were Thompson’s editor, this was how you had to work. Even in his best years, his work showed up in bits and pieces, and had to get transformed into a coherent mosaic before going out to readers.

But Thompson’s best years were clearly behind him. At the peak of his powers, he might have written a classic book on Hawaii, but in the 1980s this was not within reach. And that’s just one example out of many. Reading through the list of projects Thompson almost wrote is sad and frustrating, because they sound so promising—but they never happened.

Hunter Thompson at Mardi Gras should have been a bestseller—but only resulted in travel bills and a monumental drinking tab. Another planned book on fitness would have forced Hunter Thompson into a painful daily exercise and health regimen. That’s such a good concept, they could make it into a reality show nowadays. Other failed projects, over the years, included books on sex workers, the gun lobby, and a litany of Fear and Loathing projects that would take Thompson everywhere from Times Square on New Year’s Eve to the Masters Tournament at Augusta.

Back in those days, my friends even dreamed up imaginary Gonzo projects of our own. Let’s enter him as a driver in the Indianapolis 500. Let’s force him to play cricket at Eton or drink snake blood in Taipei. Our favorite scheme envisioned Hunter Thompson sneaking into the College of Cardinals to cast a vote when they pick a new Pope—or maybe even running for the office himself, as he once did for Sheriff.

But these were pipe dreams. Just collecting his own earlier pieces into a compilation led to extreme writer’s block. When Thompson’s career-spanning compilation Songs of the Doomed came out in 1990, another extreme intervention was required. Editor Jim Silberman only got his hands on the manuscript because Thompson’s intern waited until the author was napping, and then sent it off to Simon & Schuster in a FedEx. Thompson was furious when he found out, but calmed down considerably the next day when Silberman phoned to say the manuscript had been accepted and a large check would come in the mail.

Despite this history of missed deadlines and extravagant expenses, publishers kept giving Thompson more chances to redeem himself. And finally he did—but in the most unlikely setting. Thompson had long railed against the Hearst newspaper empire, yet he now signed on as columnist with the San Francisco Examiner. Here his boss would be William Randolph Hearst III.

I experienced the results firsthand at the time. I traveled frequently by commuter train into San Francisco in those days, and was an avid newshound. I’d read parts of four newspapers each day, and always picked up a copy of the SF Examiner on the late train back to Palo Alto from San Francisco.

I still recall the old newspaper vendor with hands that had permanently taken on the color of newsprint ink. He would pick up a copy of the Examiner from the stack at his feet, and fold it the same swinging motion, like a pitcher’s windup, as he handed it to me—receiving a quarter with the other hand. But, to be honest, I was usually more impressed by the vendor’s graceful movements than the newspaper itself. The Examiner was the only evening newspaper in the City, but had fallen on hard times, struggling to compete with the far more popular morning paper, the San Francisco Chronicle.

But, in a desperate move to build circulation, Hearst started taking chances with the Examiner in the mid-1980s. The paper brought in solid guest writers, and boldly hired Warren Hinckle, an early advocate of Gonzo journalism and maybe the most outrageous journalist in San Francisco (no small claim, that). But hiring Hunter Thompson was the smartest move of them all. For the first time in decades, the Examiner had a huge edge on the Chronicle.

But could Hunter Thompson actually produce a regular column each Monday? Even getting one article out of Thompson had been beyond the capabilities of most editors during the previous decade. But somehow, against all odds, the Gonzo King started meeting the deadline (well, most of the time).

It didn’t happen easily, and the Examiner needed to provide constant handholding, encouraging, bullying, as well as editing. But Thompson was writing again, and at a high level. Almost anything or everything could show up in these columns: sex, drugs, rock and roll, politics, sports, or just stream-of-conscious memoir. I was fortunate to read those articles at the time—almost nobody outside of San Francisco had access to them—and they stood out from anything else in those other esteemed newspapers I bought each day.

When these articles later showed up in book form, they got nominated for a Pulitzer Prize—and deservedly so. And even after the Examiner gig ended, Thompson continued to publish similar pieces elsewhere. But the short form was the limit of his comeback. There were no big books left in Hunter Thompson.

Books came out under his name, but they always drew heavily on previous writings. These included three volumes of Gonzo Papers, collections of letters, and Kingdom of Fear—the latter promoted as a memoir but, once again, drawing heavily on old material.

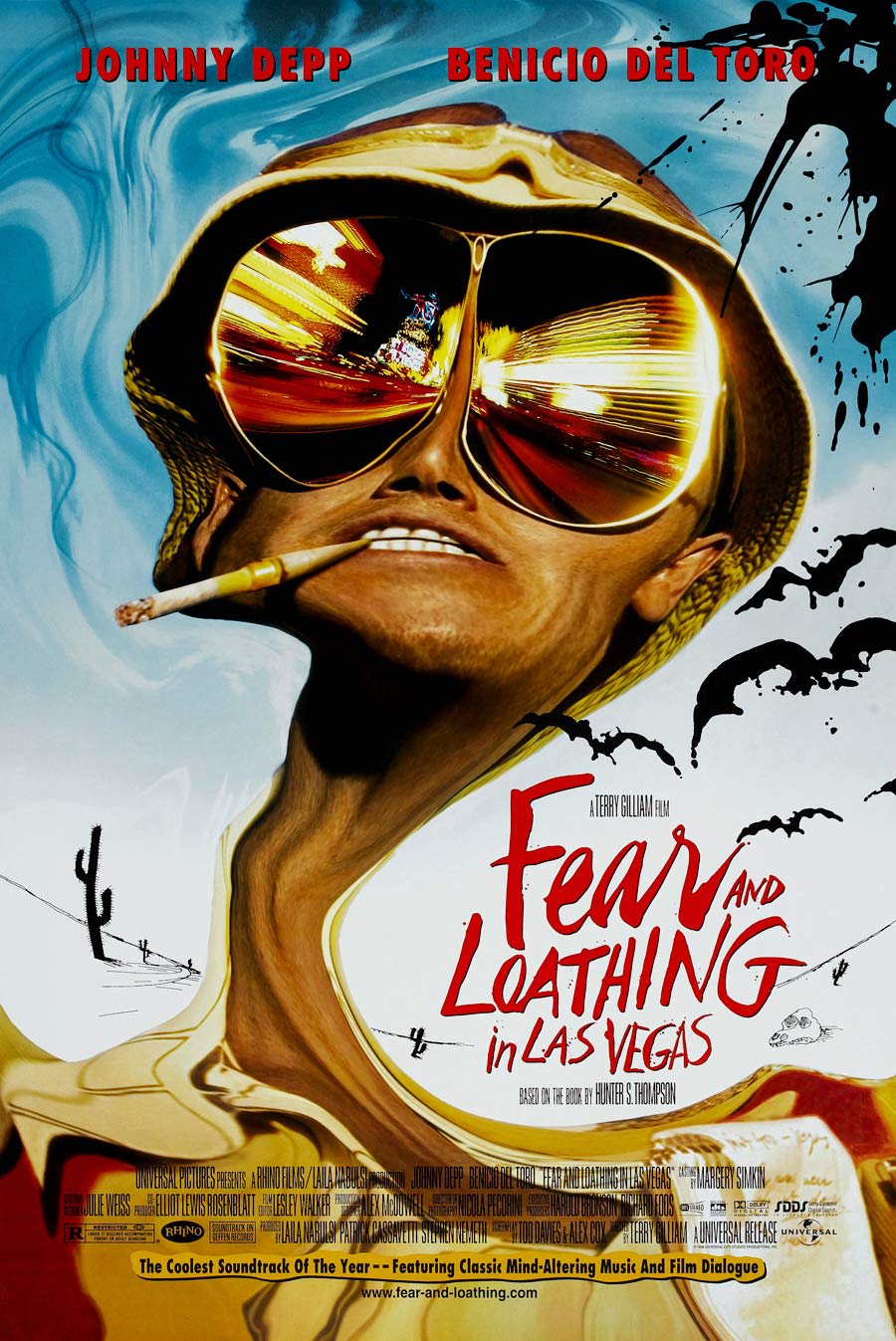

Hollywood also came knocking. Films were made with Thompson played on screen by Bill Murray and Johnny Depp. I don’t think these worked as well as the books themselves, but even a more charitable assessment couldn’t hide the fact that this author was more an icon from the past than a force on the literary scene.

Thompson himself was in bad shape. Gonzo journalists are not fine wine, and don’t age well. Meanwhile the pressure to live up to his outrageous reputation also took a toll. Perhaps there was no way Hunter Thompson could have aged gracefully—if there was, he never found it. If he had, audiences probably would have rejected it.

The sad futility of his old age was especially evident when Thompson tried to write a story for Playboy on a Sean Penn film shooting in New Orleans. When the blowout cast-and-crew party took place at Arnaud’s Restaurant, all the celebrities romped and reveled in a private room upstairs, but Thompson couldn’t get up the steps in his wheelchair.

He might have asked a few people to carry him up the stairs. But that would have been a shameful entrance for a man who always wanted to dazzle the audience. So he stayed in the bar downstairs, drinking in private while the party went on above.

He wouldn’t take on another assignment like this. In fact, Thompson was dead even before the movie came out.

He killed himself a few days after the New Orleans party. Cause of death was a self-inflicted gunshot, not much different from what his role model Ernest Hemingway had chosen years before.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that both Hemingway and Thompson nurtured macho public images that became even better known than their books. I will leave it to others to debate whether suicide, for such individuals, is a courageous, manly act, or the exact opposite. It suffices to point out here that a celebrity author’s public image can grow so huge and demanding that no space is left for the frail and fragile private lives we all must live, sooner or later.

But even if Thompson had survived, squeezing a couple more decades out of the worn tube of his body, he wouldn’t have found himself at home in the digital age. I’ve written elsewhere about the system’s hostility to the counterculture in our own times. And nobody—and I mean noooobody—countered the culture with more vehemence and defiance than our late and mourned Gonzo King.

But even if our age is indifferent to his type, we need another Hunter more than ever. The whole country—hell, the entire planet—looks more and more like Las Vegas every day. The campaign trail is uglier than it ever was. Fear and loathing are endemic, almost an established way of life.

This is where I should end by saying: At least we have those books. But instead I’ll entreat some young journalists to read them. To emulate them. To comfort the weird and weird out the comfortable. The culture and its ruling authorities and institutions will resist all this, but that’s exactly why we need a huge dose of Gonzo today.

So my final assessment is that, yes, we have the books. And that’s merely the start.

.png)

![Better Data Is All You Need [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/opera.png)