Alongside the legions, the miliaria marked the power of the Roman Empire. Placed every mille passus or Roman mile (1,478.5 meters), these cylindrical or rectangular stone markers punctuated the Roman roads, much as kilometer posts do on highways today.

A large group of researchers has turned to the latest technology to delve into historical and archaeological records in order to reconstruct the road map from 2,000 years ago. What they discovered is that it was far more extensive — almost twice as large as previously believed. They also found that very little of its original layout remains. The results of their work, published in Scientific Data, have been compiled and made publicly available on Itiner-e, a digital atlas of the roads that began or ended in Rome.

“When you walk along a sunken path worn down by time and travelers, people still say, ‘this used to be a Roman road,’ but the Romans built them to last,” says Pau de Soto, of the Archaeology Research Group at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and lead author of this impressive study. “Another misconception we wanted to dispel is that they were paved with stone slabs, like the Via Appia. In fact, they were built in successive layers of gravel, each finer than the last, with the top layer made of compacted fine gravel. That was best for horses, which at the time still didn’t wear horseshoes,” adds the archaeologist.

Like modern roads, they were raised above the surrounding terrain and given a slight slope to drain water. “The first modern roads were built following the Roman model,” the archaeologist notes.

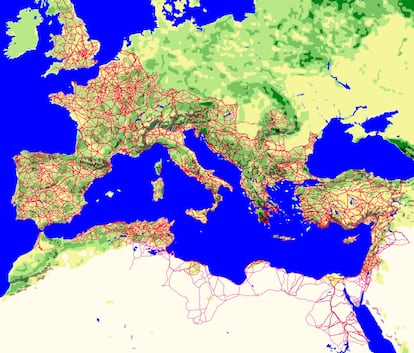

The roads connected the entire Roman Empire, which at its height stretched from present-day Scotland to the eastern edge of the Sahara; and from the Black Sea to the Moroccan coast.Itiner-e

The roads connected the entire Roman Empire, which at its height stretched from present-day Scotland to the eastern edge of the Sahara; and from the Black Sea to the Moroccan coast.Itiner-ePau de Soto and some 20 researchers used modern GIS (Geographic Information System) techniques to unearth the layout of the Roman roads. “GIS is the foundation of modern archaeological research,” says the UAB researcher.

They combined historical texts such as the Itinerarium Antonini and the Tabula Peutingeriana — the closest thing to a road map from antiquity — with studies on archaeological sites and books on Roman history. “But we also used 19th- and 20th-century topographic maps, postwar aerial photographs taken by the Americans, and satellite images; GIS allows you to combine data from all these sources and project it onto the terrain,” De Soto adds.

The result of combining so many sources is that, around the year 150 CE — when the Roman Empire was at the height of its expansion, spanning about four million square kilometers (1.5 million square miles) — the network comprised 299,171 kilometers (about 186,000 miles) of roads. This figure adds more than 100,000 kilometers (62,000 miles) to the 188,555 kilometers (117,000 miles) counted in earlier studies and is equivalent to circling the planet seven times. In Spain alone, the length of Roman roads exceeded 40,000 kilometers (24,850 miles) — twice what had been estimated. At that time there was no radial distribution centered on Madrid, as with modern highways, but from cities like Augusta Emerita (Mérida), the capital of Roman Lusitania, several major routes branched out.

The authors of the new study estimate that one-third of the roads connected the main urban centers, while the remaining two-thirds were secondary routes linking settlements on a local or regional scale. However, they found that there is certainty for only 2.7% of the total mileage. “That’s what still survives or has been excavated in archaeological work,” De Soto explains.

For the vast majority of Roman roads — nearly 90% — there are only traces suggesting where they must have been: “In landscape archaeology we call them fossilized axes, which might be a Roman bridge, remnants of a road at a city’s outskirts, or the discovery of a miliarium,” says De Soto.

Everything indicates that a road must have linked those elements. What GIS does is model the most plausible route between them, taking into account the terrain’s topography — such as a mountain pass or a river crossing. Another 7% of the map’s total is purely hypothetical: if two Roman cities lie close to each other and both have road remains at their exits, it’s reasonable to assume they were once connected by a road.

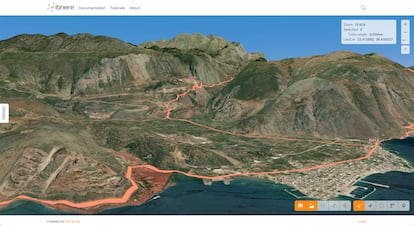

Thanks to GIS tools, Itiner-e maps each road on the ground, connecting available points such as Roman bridges or milestones, and taking topography into account. The image shows the mountain passes to ancient Delphi in Greece.Itiner-e

Thanks to GIS tools, Itiner-e maps each road on the ground, connecting available points such as Roman bridges or milestones, and taking topography into account. The image shows the mountain passes to ancient Delphi in Greece.Itiner-e“The Roman roads—and the transport network as a whole—were absolutely crucial to maintaining the Roman Empire,” says historian Adam Pažout of Aarhus University in Denmark, a coauthor of the study. “The Romans devised an intricate transportation system made up of inns, roadside stations, and relay points for couriers and public officials traveling across Italy and the provinces,” he recalls.

For Pažout, “the roads formed a framework that allowed Roman power to be projected — whether through the army, the law, or administration — and that held the Empire together.”

According to the authors, their work will allow for a better understanding of Rome’s history. Along these roads, millions of people traveled, new ideas and beliefs spread, and Roman legions and merchants moved between the far-flung corners of the three continents that made up the Empire. But these routes — whose immense reach is only now being fully revealed — also helped spread diseases and plagues such as the Antonine smallpox or measles epidemic, and the Justinianic bubonic plague, both of which weakened the Empire. They may even have served as the pathways for successive barbarian invasions.

What remains of the Roman roads, though not many miles in physical length, still forms part of Europe’s framework. As archaeologist Pau de Soto reminds us: “Europe’s urban fabric is a legacy of Rome. Most European cities already existed in Roman times — and were already connected to one another.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

.png)