Carbn defined my career.

For 2 years, I was the tech team of a tiny climate-action startup. I built a mobile app, and multiple backend architectures, from scratch, with close to zero experience.

When I started out my career at Deloitte, I was the classic case of the temporarily embarrassed young billionaire. Body buzzing with energy and undiagnosed ADHD, mind buzzing with dreams of greatness, yearning to someday do a startup. But, unlike my corporate colleagues, I had something my consulting companions didn’t have: I kept not getting promoted*.

*I was basically much too annoying to put in front of clients.

After the annual consulting tradition of “I’m leaving, for real-sies this time”, and some performative job applications to Revolut and Monzo, a recruiter got me in touch with something they thought would be right up my alley.

A commercial strategy consultant, with some cash, validated market research, and a dream, was searching for somebody with energy and a strong technical background to build an app in a potentially huge new market: Carbn.

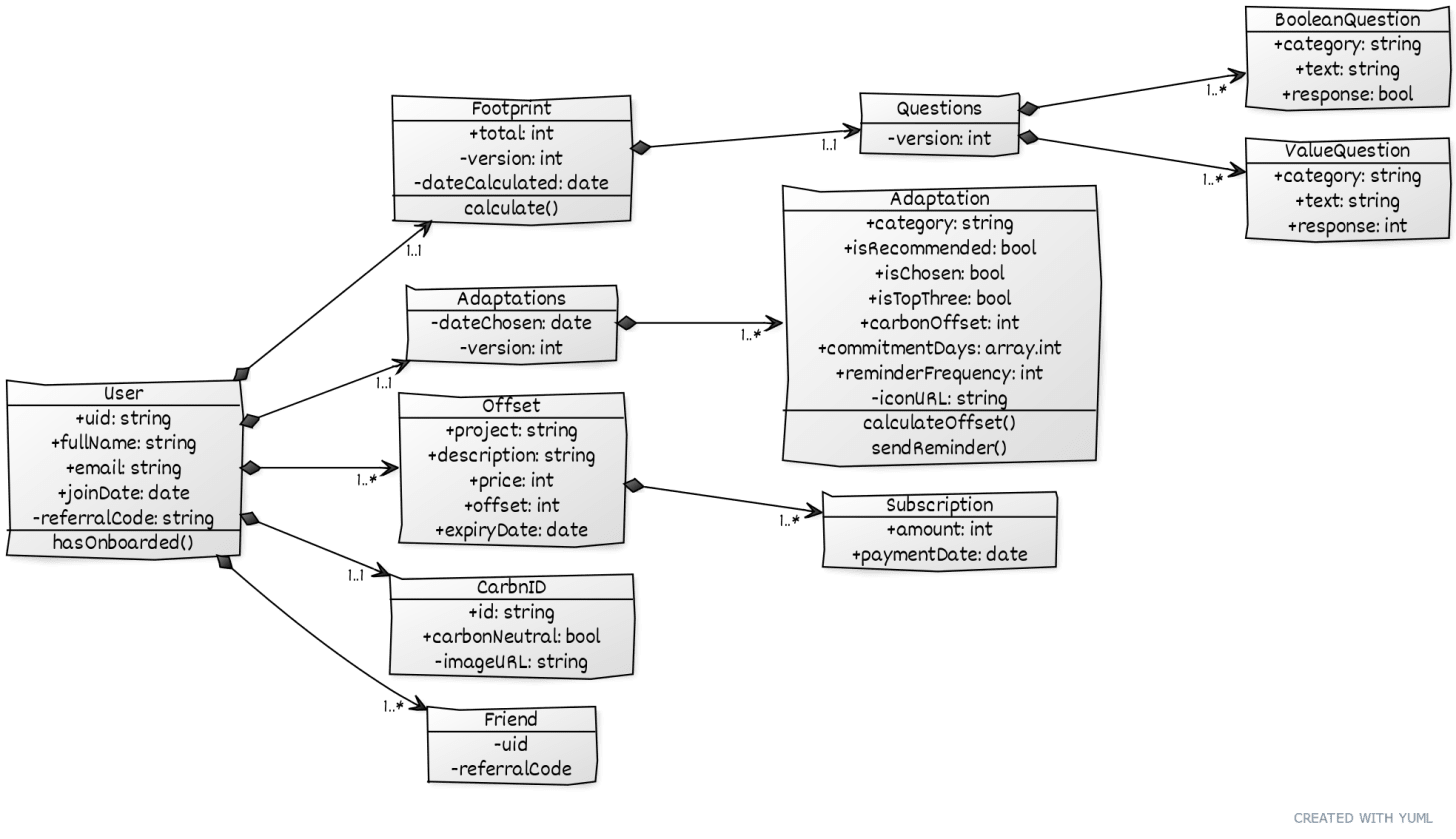

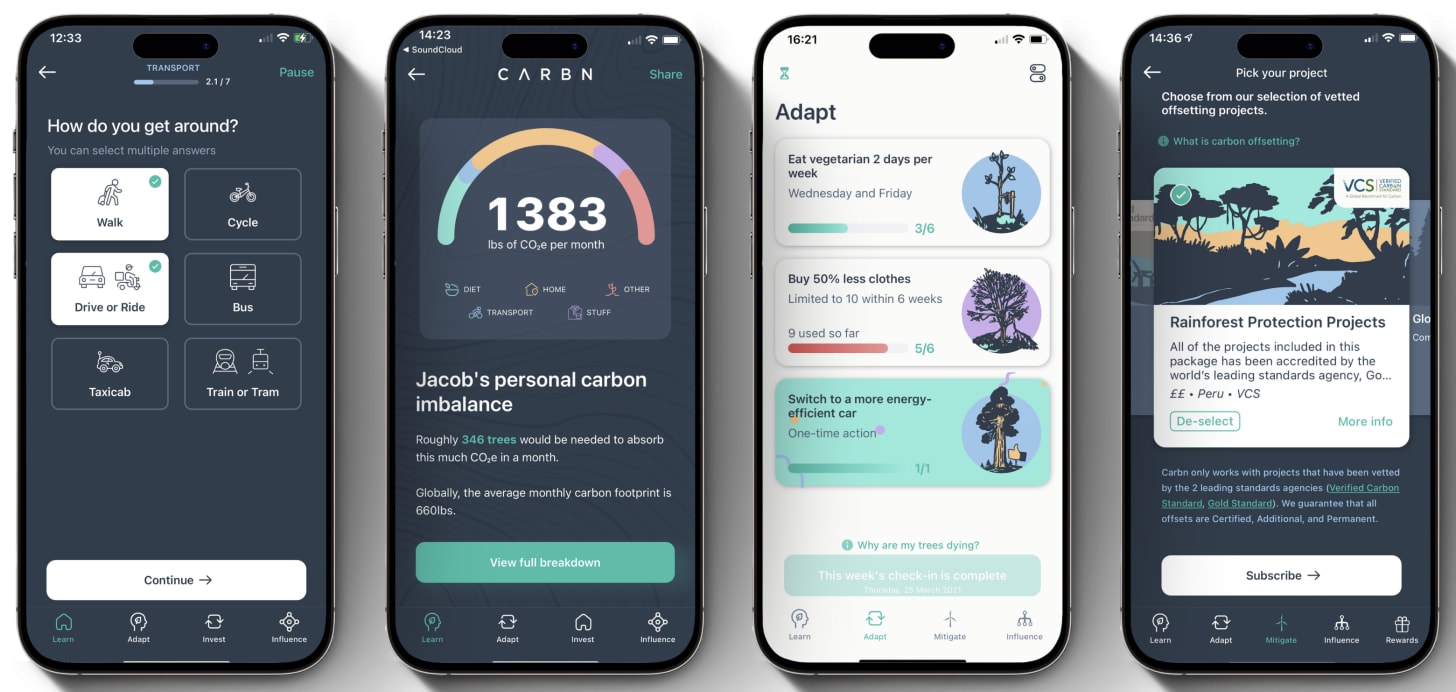

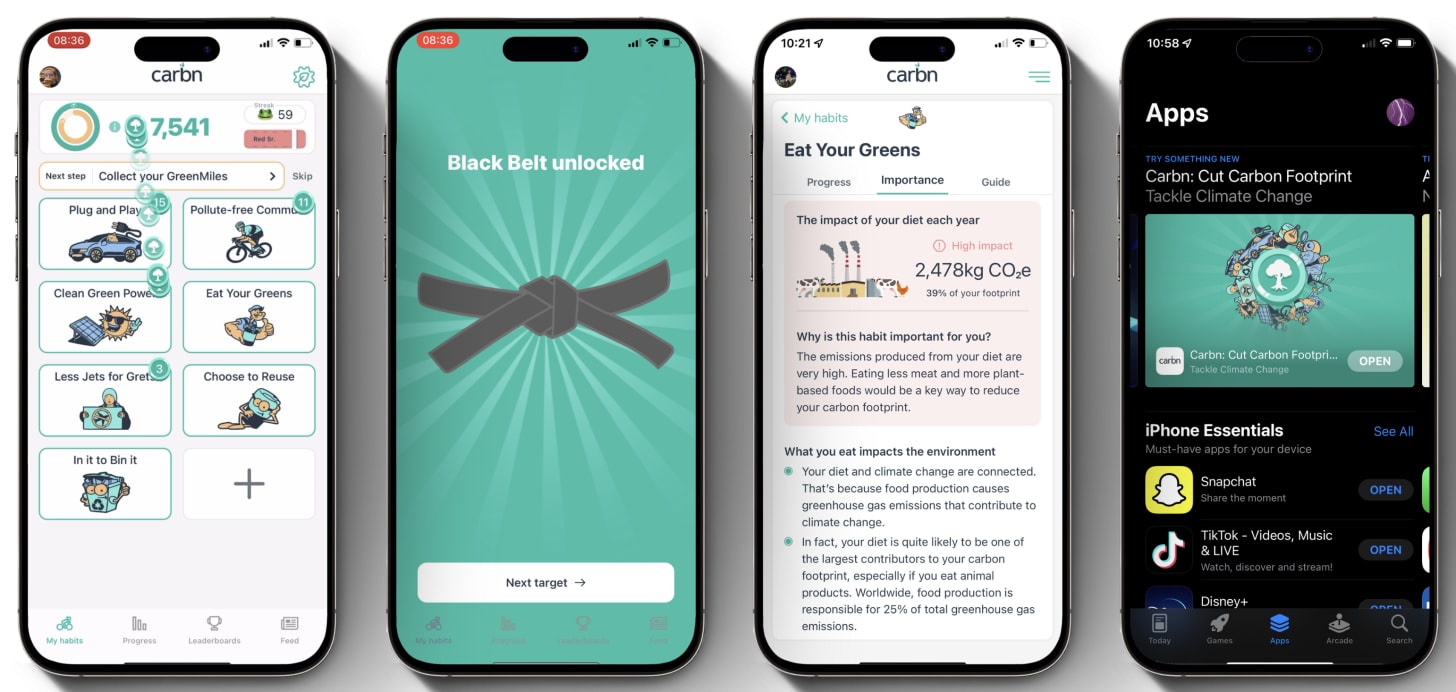

Carbn was a gamified app that simplified climate action. Calculate your footprint, adapt your lifestyle, and pay for carbon offsets. It was peak late-2010s-ZIRP-era stuff. You honestly could not build this in 2025. But at the arse-end of the COVID lockdowns, the idea was catnip.

It was exactly what I’d daydreamed of for 4 years.

The founder and I immediately agreed to work together and became fast friends. I was the technical co-founding Camilla to a bootstrapping King Charles. I was offered generous double-digit equity, alongside a salary only slightly below what Deloitte paid their mid-level devs / janitors.

Today, I’m telling the story of the systems I created. The decisions I made as the tech cofounder to carry an app business, from scratch. We’ll look at:

The initial, rudimentary, backend architecture our MVP shipped with.

The “scalable” monstrosity I designed once we landed £200k in funding.

What I should have done all along.

At no point did I know for sure what I was doing. But that’s part of the fun.

Subscribe to Jacob’s Tech Tavern for free to get ludicrously in-depth articles on iOS, Swift, tech, & indie projects in your inbox every week.

I’ve recently created a new category of article to write about my rollercoaster of experience in and around startups: war stories. Contact me if you have a wild tech war story you’d love to share with the world!

This email can be too long for many email clients, so please read on my website for the best experience.

As well as from my memories of 2020-2022, this article was reconstructed in large part from old Apple notes I took at the time, as well as floating bits of documentation and code that remain on my old laptop.

While running down the clock on my notice period, I was jogging through the park and imagining the perfect technical architecture. I’d recently completed the second-easiest AWS exam, Solutions Architect Associate, so knew all about how to structure a big system. Vaguely.

I closed my eyes among the trees at Avery Hill and pictured a serverless wonderland, with SQL queries skipping among the Lambda functions. Serverless was the future, I think. I even went full MBA with my consulting training:

What are some KPIs and OKRs for Carbn?

Do we have a balanced business scorecard?

Will we need a data lake, or perhaps a dashboard?

Outside the glaring blind spots in my architectural knowledge, I had a reasonable understanding of my own strengths and weaknesses as an engineer. I was quite good at building quickly. I was relatively slow at picking up new tools. I could usually work things out. I knew a decent bit of SwiftUI*.

I was between iPhones after leaving cosy corporate life, so actually, the first couple of features were UIKit, since I was lent my mum’s old iPhone 6+ which only went up to iOS 12. I was frankly pretty okay at mobile apps, so this piece is more focused on pointing & laughing at my backend setup.

We had a tight 2-month timeline to ship our initial MVP, and I was self-aware enough to know I couldn’t learn how to whip up a backend in that time.

There's a known solution for mobile devs with limited backend capacity: Firebase.

Been there, done that, met Peter Friese, got the tee shirt.

As an instinctive contrarian, I needed a way to use Firebase without feeling like I was using Firebase. In 2020, options were limited, primarily because I’d never heard of the nascent Supabase.

Enter AWS Amplify: Amazon's answer to Firebase. This was a competing platform-as-a-service (PaaS) that directly mapped core functionality to corresponding AWS services, offering a tempting conversion route directly to running our own cloud infra.

This held the solution to one non-negotiable technical requirement from my cofounder: working offline. For the climate-conscious yuppie on the go. Amplify was batteries-included with a sync engine, making it an obvious go-to.

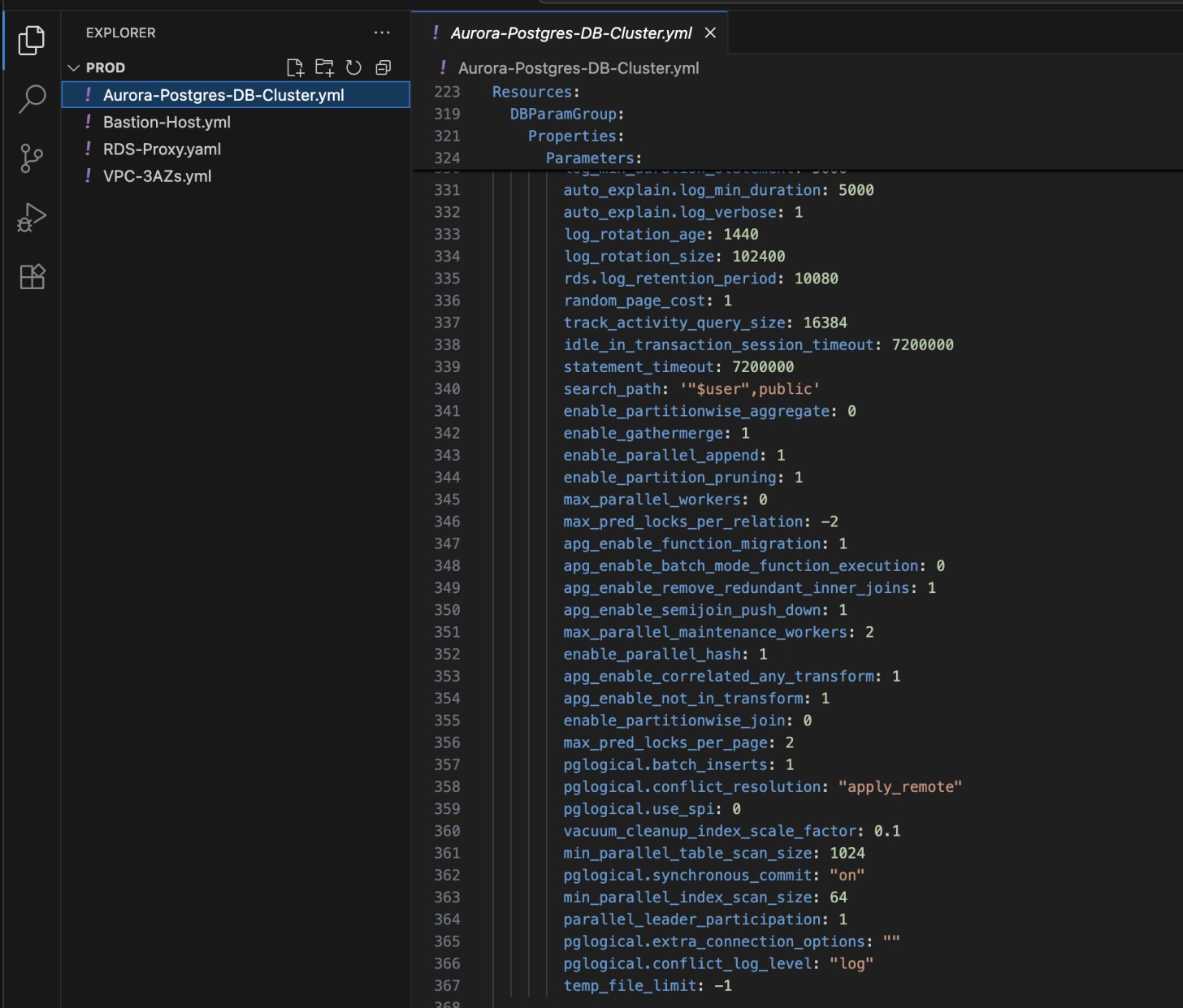

As I began work, I meticulously crafted an architecture diagram in the hope that this serious piece of engineering planning would pay dividends.

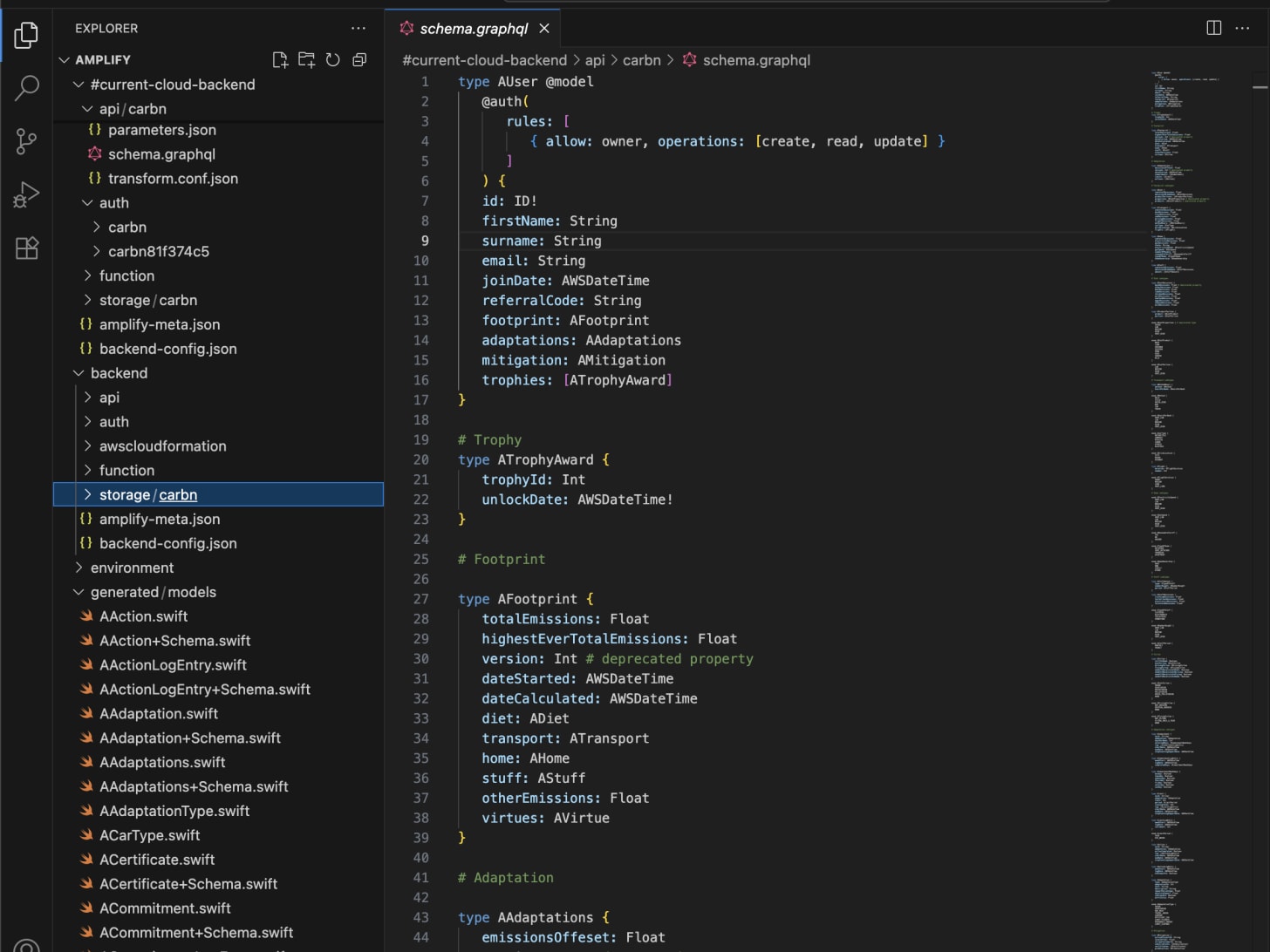

The tech stack utilised the full Amplify toolkit:

AppSync and GraphQL for networking

DynamoDB for data storage

Cognito for email address & social authentication

S3 for profile pic file storage

Lambda serverless functions to run our Stripe integration and sell offsets.

Back in the day, none of the big open source PaaS toolkits supported SQL databases, so SQL vs NoSQL wasn’t even a consideration (yet). We were locked-in. All our data was stored as a big JSON tree, one per user:

Anyone who’s built a complex system on early PaaS tools will run into limitations, hard. AWS Amplify is magic when shipping an MVP, but it has myriad invisible guardrails that twat you in the face as soon as reach out for flexibility.

Our data lived in DynamoDB and that was that. Our users were effectively sovereign islands, isolated by the limitations of NoSQL. I couldn’t find any obvious built-in way to create many-to-many relationships between users for our upcoming social features. It goes without saying that they were trapped in Cognito’s auth directory. AWS and their damn free startup credits does a fantastic job of locking you into their ecosystem.

The bane of my existence, though, was the mandatory GraphQL.

Never trust an API so complex your networking code needs to be auto-generated. Or one that you have to re-learn every time you want a new ‘endpoint’. It was just a lot of ceremony, man.

Amplify’s DataStore, their persistence-framework-slash-GraphQL-sync-engine, might have been worse. Array data types didn’t really behave like you expected, often overwriting themselves due to confusing conflict resolution rules. I was in a hurry, so instead of learning the idiomatic approach to implementing one-to-many NoSQL, I picked the option labelled “optimistic concurrency” to unblock myself and moved on.

You wouldn't believe how long it used to take to ship apps before Claude Code. But with some smart scope cutting, we released after about 3 months of work, complete with:

The world’s most accurate™ Carbon footprint calculator

Smart suggestions to improve your footprint over 6 weeks

Carbon offset subscriptions via Stripe payments

The product was just about good enough to persuade an angel investor to take a bet on our founding team.

Fresh off a funding round, we had a cool £200k in the bank. I took a cheeky 3-week break to hang out with my new baby, because it’s not like we were going to get any more time together for the next 12 months.

We wanted to run cool, so just had 2 key hires in mind: a designer and another engineer. This was my first run-in with the difficulties of hiring. We interviewed some characters:

One candidate was 2 hours late (because he said he had to shower), and, when we took him for lunch, loudly made fun of the current COVID mask mandates, to our masked faces.

A middle-aged, very experienced, dev willing to work for sub-£50k, who completely ignored everything I asked him to do in the technical test. His email name was Big Chungus. Somehow in my naïvety I was still on the fence. He would have made me his bitch.

Someone claimed to have done portfolio work for Peanut, a startup that later moved in next door(!), whose founder laughed and clarified that it was a complete lie.

I very nearly hired a friend who, I realised mid-interview, had been stuck doing mindless grunt work for the last year and a half.

We spoke to someone who was briefly accepted into a startup accelerator where he tried to design the Uber for Ice Cream.

*I won’t name any names, but three of these bullet points were the same person.

There’s a lesson I can give to scrappy startups looking to keep burn-rate low: Don’t look for someone with any experience. Seriously. You want someone bright, hungry, and energetic; unjaded by the astronomical unlikelihood of their equity being worth anything. This is why the meta is to hire grads straight out of uni.

We landed a UI designer we held onto until the end, a smart graduate dev who job-hopped after a 3-month death march, and an overseas contractor we broke up with after an argument over raising the day-rate. Yes, I really truly suck at management. For the most part, I was on my own.

The biggest strategic failure of our startup was around our target market. In that, we never settled on one.

The B2C proposition promised limitless growth from a groundswell of climate activists.

The B2B path promised revenue via climate-conscious corporates wanting to achieve net-zero.

Our angel, like all self-respecting Europeans, was nudging us towards B2B because that led to cold, hard cash. B2B focused us on “Scope 3” emissions, a category which included all the emissions produced by employees on-the-job. For many Western services businesses, this is by far their biggest block of CO₂.

But business clients require a rethink of our data architecture. They love a good report, thrive on aggregation, and get a little tight at the trousers for dashboards. NoSQL just isn’t a good fit for this use case. We wanted organisation-level data that piped directly into ESG reports: Employee carbon footprints, summaries across departments, and internal leaderboards that can spark friendly competition between teams.

The basic day-to-day usage of the product also transformed: we wanted to track employee daily habits as they became greener, and gave them Greenmiles every day (I coined the term, like corporate air-miles but for the planet). We fudged the numbers until 1 Greenmile = ~1 mile of driving.

To implement this, we needed relationships between users and their organisations, to-many tables which grew indefinitely for logging, and complex queries for environmental reporting. We needed something relational.

AWS Amplify was no longer suitable for our needs.

I thought to myself, “I’m pretty self aware. I’m better at infra than I am at actual backend”.

This is a lot of hubris for somebody who didn’t know what a connection pool was. I already knew what I wanted to do. I wanted something that scaled. Something that would run the same whether we remained at low-thousands of users or the impending millions.

Coincidentally, two days before I started to set my design upon the world, a tutorial was released by AWS, with exactly what I wanted: Python code using SQLAlchemy, running on AWS Lambda functions, in front of a relational database. It was everything I needed.

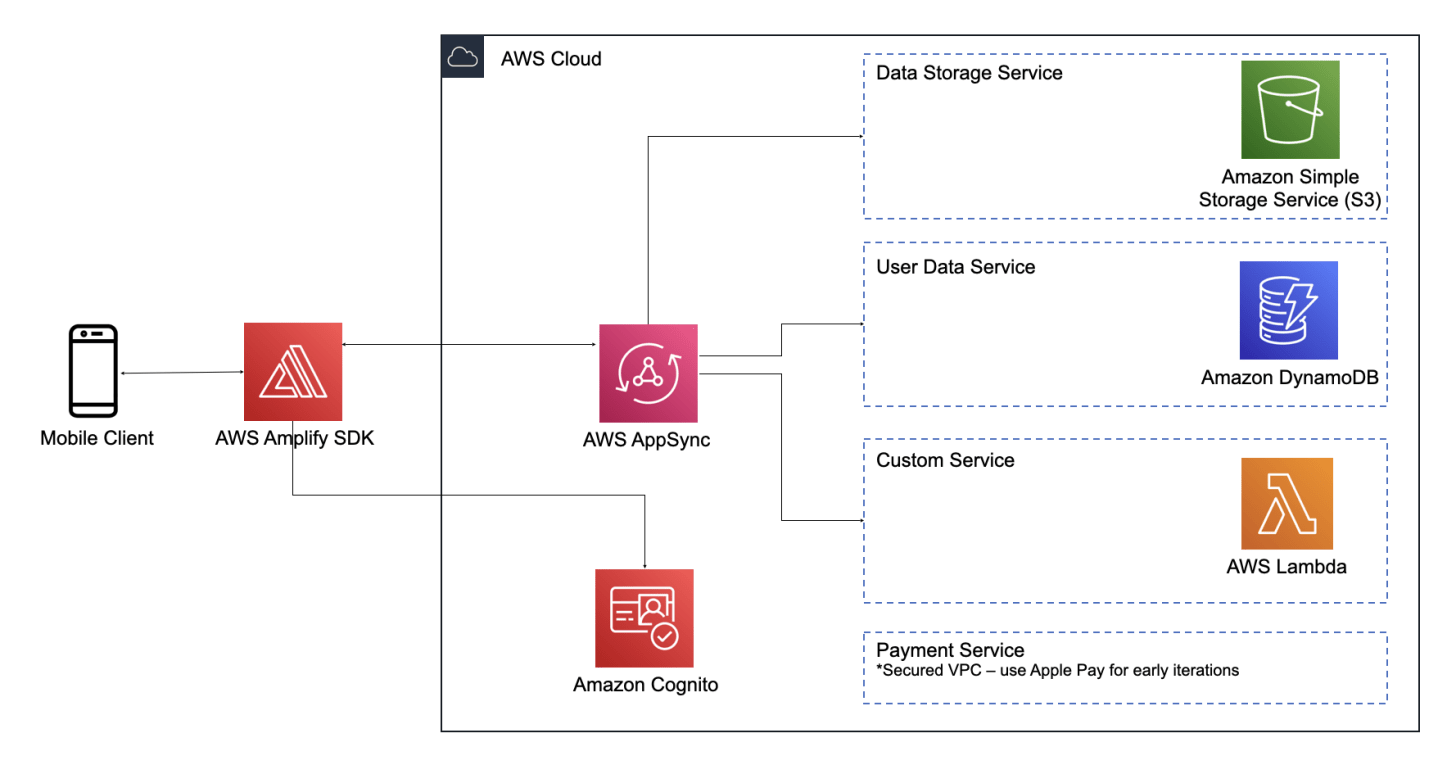

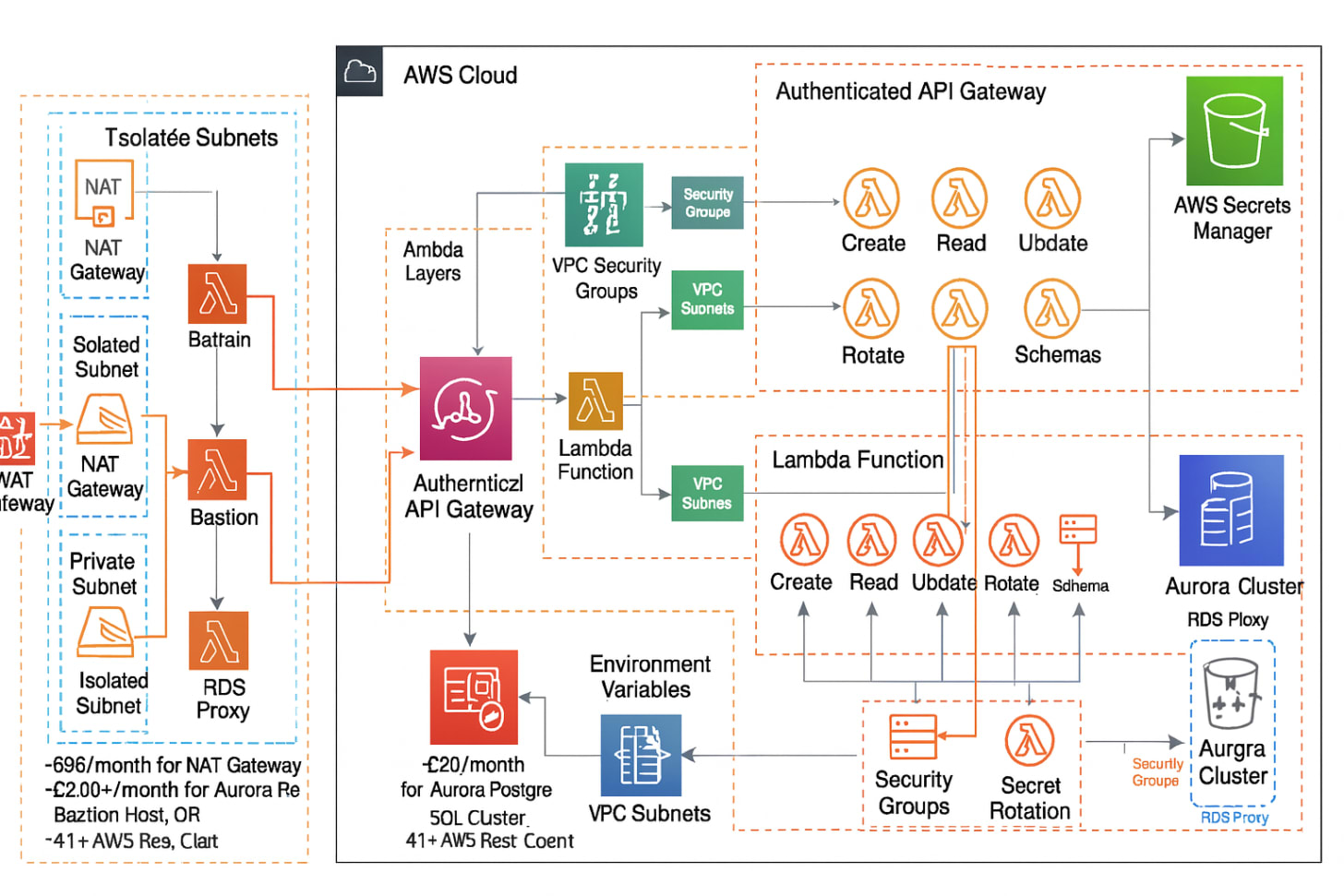

This architecture diagram is a gigantic understatement. I vibe-tutorialled myself into a well architected, highly available, and ludicrously heavyweight infrastructure. Thousands of lines of YAML that spanned:

VPCs set up across 3 separate availability zones

NAT gateways and Bastion Hosts for each AZ

An Aurora Database cluster with an RDS proxy

Plus a separate “test” environment too, but I managed to swing just 2 AZ’s.

The above diagram doesn’t really communicate the scale of fuckery I was doling out, but fortunately, this delirium fever dream, courtesy of ChatGPT, is actually spot-on.

This enterprise-grade architecture would have been fine if I was serving 100k DAUs, and high availability was an existential business constraint. But I had built a behemoth I barely understood.

I had tons of firepower at my disposal, but honestly, I had my fingers crossed, hoping the main DB would never shit the bed and I’d need to work out how to restore the backup on-the-fly.

Altogether, this infra put us back ~£600 a month.

This was around 50% database, 48% networking infra, and 2% compute.

If there was a perfect example of failing to see the forest for the trees, the secondary reason for using Lambda functions for our application code was that it was meant to be cheaper than a provisioned server!

In other words, ~1% of our runway a quarter. Not great, not terrible.

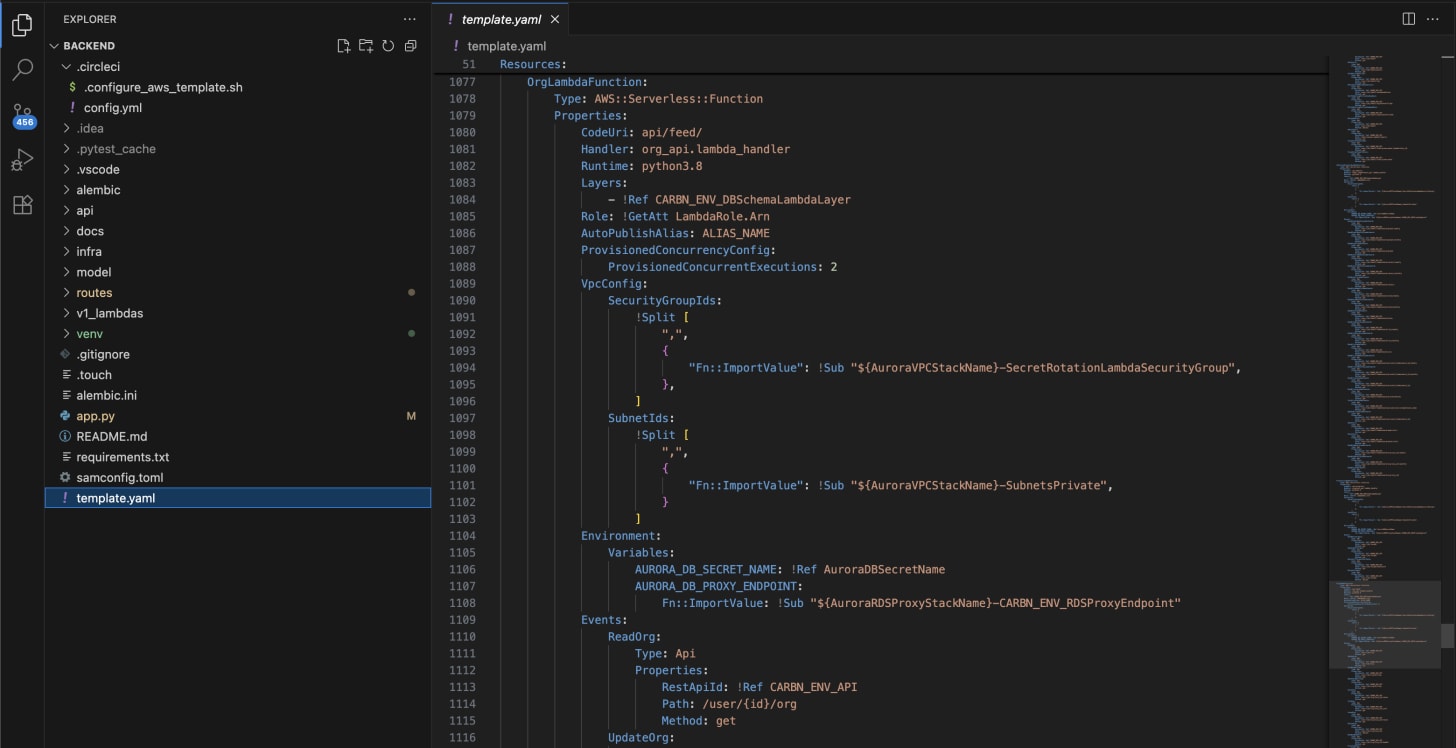

Once my nightmarish serverless database setup was there, it was pretty nice to work with: all my Python ran in separate Lambda functions that could be individually mapped to endpoints I set up via the AWS API Gateway.

REST ENDPOINTS.

I really did have a sweet development workflow.

Locally, I rolled a Flask app that ran the Python APIs, calling into a local PostgreSQL DB on a Docker container. I could build the DB migrations and application code, run the local server, and code the iOS feature against it.

It never occurred to me that this low-energy setup might work just fine on the server. But I was emotionally invested in my architecture. I could be smarter than that.

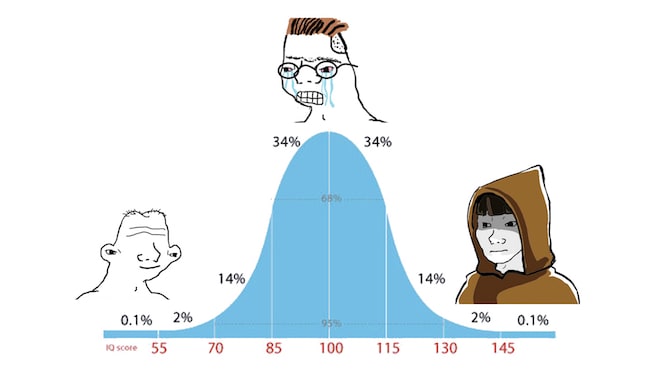

Humans contain multitudes. An internal IQ bell curve. Some days, maybe after a sesh at the pub, you might be below your best. When you’re nailing it, on a cool 8 hours sleep* and full of energy, you might be killing it.

*someone without kids remind me what this is like, please

But there was one day where I blew myself out of the water.

I worked out how to deploy my infra via CircleCI every time I pushed to main, using AWS SAM and some truly unhinged scripting. This was simultaneously the smartest and dumbest I have ever been.

On Flask, we had to import models via model.layer.python. But on Lambda, the file hierarchy was flat, with all imports flattened to the same root directory.

This sed command was the cornerstone of my workflow, converting every single Python file:

# Before (local development) from model.layer.python.user import User # After (Lambda) from user import UserMy pre-deployment script ran a find-and-replace across the whole entire backend codebase to make the imports work.

We’re barely scratching the surface.

For our Stripe payments, I needed to inject the payment processing server IP into the Lambda function environment, so, naturally, I hardcoded the required IP in the pre-deployment script, which then added it to the Lambda template.

You heard that right: in attempting to create a sustainability app, I hypocritically hogged two entire IPv4 addresses.

The pièce de résistance was my hack to migrate the database schema. I needed to run these migrations using Alembic on deployment, so I set up a custom Lambda function, with a random hex name that triggered automatically:

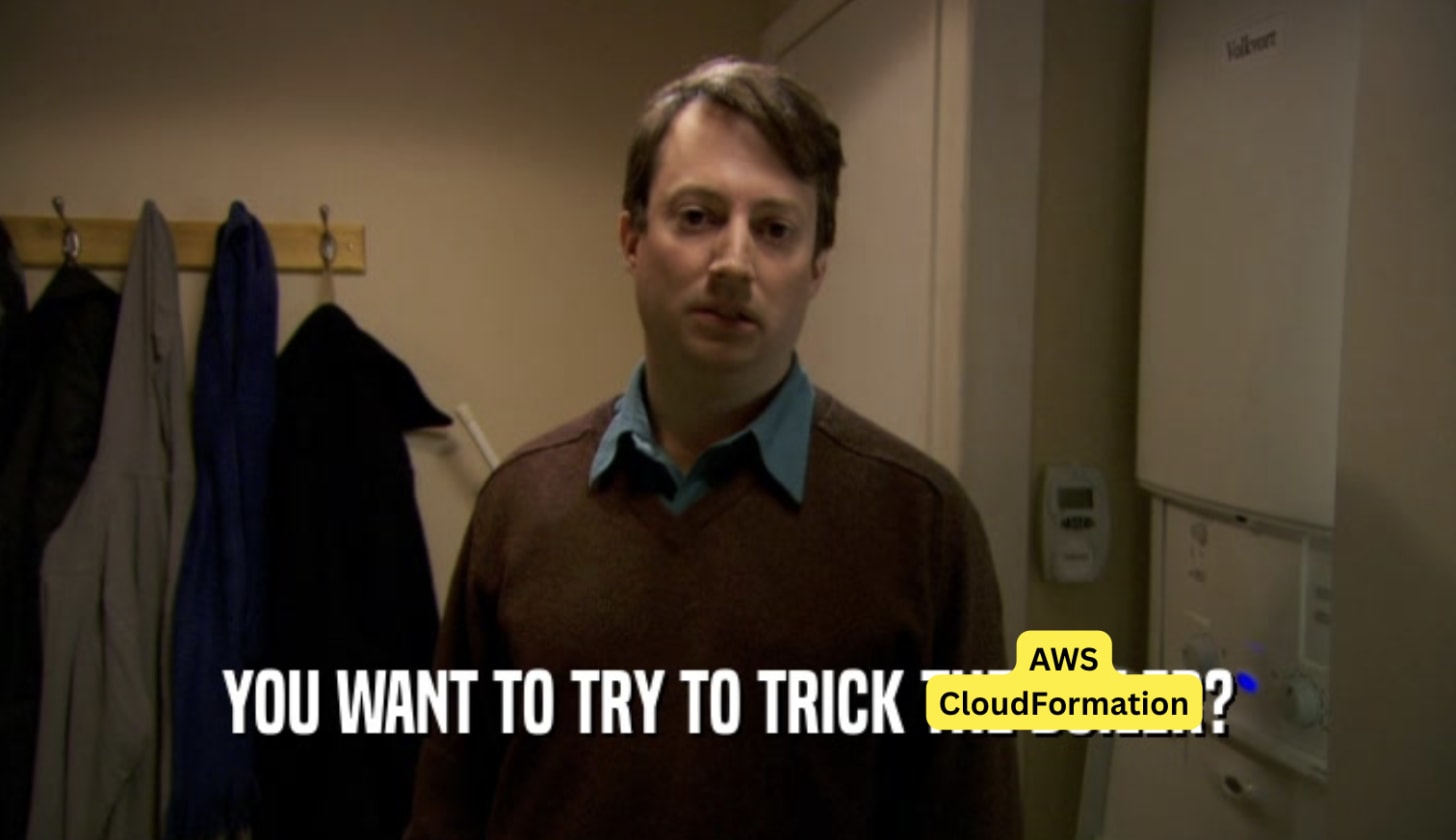

I was a crab, in a knife-fight with the CloudFormation lobster, shanking my infrastructure-as-code until it submitted and agreed to perform DB migrations on-deploy. The random name was there to trick CloudFormation into thinking the function was new, and therefore running the migration code it contained, on every deployment.

If there’s anything we can learn from this, it’s that anyone can do a startup when they put their mind to it.

I eventually came into my own.

Looking at my old Apple Notes, I wasn't being a complete idiot, because I was starting to consider the sorts of problems we might need to consider when managing systems: server-side caching, pre-fetching, profiling the slowest API calls, looking into performance of database queries, cold start times of Lambdas, deprecating old APIs, and creating proper OpenAPI 3.0 documentation.

Performance is great, but I should have invested properly in observability, disaster recovery, and alerting. I vividly remember the day I had to ship a 1-line production fix, and CircleCI had an 8-hour-long incident blocking my deployment.

Without proper alerting, we were pretty much waiting for people to tell us about incidents. I vividly recall a Zoom call with a recruiter who told us that Sign In With Apple was broken.

I recall another weekend where we took a trip to Hastings, and login was inexplicably broken. I managed to diagnose and ship the hot-fix just as we arrived from the 2-hour drive.

Sometimes, as a sole developer, marketers will just make things your problem. In two startups now, I’ve had a marketer up my arse complaining that our ads weren’t targeting iOS 14+ users (both times, it was a toggle they needed to select in the console).

None of this was that bad, because we didn't have very many users. I wasn’t under any pressure to teetotal or to avoid flights. But being a single point of failure for over a year is not an enviable position.

At the load we were dealing with, this whole project really could've been set up on a £5/month VPS on DigitalOcean or Hetzner. The structure would look near-identical to the existing development workflow I had set up.

A single VPS running a Docker container with…

PostgreSQL database

Flask app container running my Python API

Nginx reverse proxy to forward requests to Flask

Keep Cognito auth, validate JWTs in Flask

A simple backup script that replicated my database to S3 every day

This would've handled 10k daily users easily. Okay, maybe a $20-50 server would cover our bases in the event of a serious unanticipated traffic spike. These bad boys can scale-in-place in a minute or two of downtime.

If I wanted to stick to AWS infra and give us escape hatches, we could have deployed the whole app using Elastic Beanstalk, their infra-as-a-service starter pack. Incidentally, after we folded, I spun up this exact environment on an Elastic Beanstalk server+database package. It cost £20/month.

I fixated very hard on scalability before simplicity. Worse, I failed to discuss my plans with anybody who might have known what they were doing. We had no in-house technical expertise past what I could work out for myself.

Anybody with a bit of infra (or startup) experience under their belt could have told me to chillax, and showed me how a single server and simple file-based DB or miniature Postgres instance would easily carry us through to a seed round.

The thing is, though, the infra kind of did the job. I made it work, it was just ludicrously over-engineered for our scale. Yes, there were some dirty hacks. But they were my dirty hacks. I smashed out the backend within a couple of weeks, migrated all our data over, and then the backend was out of my way while we focused on making a compelling product.

The gargantuan infra setup barely scratched our burn-rate, and we were running cool because we were paying ourselves pennies.

Our B2B proposition didn't end up leading to any useful sales, but Greenmiles inspired the new B2C value proposition, as we’d finally stumbled upon a compelling daily use case.

We reoriented the app around Greenmiles and “Ten Green Habits”. Apple liked it.

I'm not a systems architect or a backend engineer. I'm a hacker. I get something working and get it out of my way.

The backend was a zero-to-one deal both times. I needed a rudimentary backend to support our MVP, so used AWS Amplify. Then, when user requirements changed with our B2B, I responded by setting up some incredibly convoluted serverless SQL infra.

The best flow states of my life were the utter zen as I hacked away, seamlessly shuffling between backend and frontend as I built a feature and the API in tandem, like Claude Code 1995 Edition™.

It’s fun to point and laugh at my unhinged attempt at creating a scalable architecture. Because it was funny. I spent a week cobbling together an enterprise-level serverless architecture held together via dodgy deployment scripts, duplicitous Lambda function migration triggers, and PVA glue. The architecture I created was only possible with the confidence of a 25-year-old Deloitte graduate with the second-easiest AWS certification.

And it’s pretty damn bad that I never drilled any disaster recovery process, never had any real production alerting set up, or sanity checked my work with someone who knew what they were doing. I should have kept it simple.

But, on the other hand, I bought myself operational silence so I could focus on the product. I never had to think about my infra again, it just worked.

Because as a cofounder, I wasn’t just building a backend, or even just a mobile app. I was bouncing ideas off my cofounder, recruiting engineers, pitching to VCs, studying our analytics, and chatting to users.

But as a technical cofounder, the buck also stopped with me. All the problems were my problem. I developed the superpower of being able to hold my face against an industrial sander until I solved the obscure Lambda issue or Auth bug.

And these skills defined my career.

.png)

![Slicing and Dicing Through Complexity with Hanami [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)