Welcome! Glad you could join us for another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our slate:

1) Digital animation on film stock.

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

Toy Story used to look different. It’s a little tricky to explain.

Back in 1995, CG animation was the topic in the industry, and Pixar was central to the hype. The studio had already shifted Disney to computers and won the first Oscar for a CG short (Tin Toy). Giant movies like Jurassic Park incorporated Pixar’s software.

The next step was Toy Story, billed as the first animated feature to go all-CG. Even after Pixar’s successes, that was a risk. Would a fully digital movie sell tickets?

It clearly worked out. Toy Story appeared 30 years ago this month — and its popularity created the animation world that exists now. A new process took over the business.

But not entirely new — not at first. There was something old about Toy Story’s tech, too, back in 1995. Pixar made the thing with computers, but it still needed to screen in theaters. And computers couldn’t really do that yet. From its early years, Pixar had relied on physical film stock. According to authors Bill Kinder and Bobbie O’Steen:

[Pixar’s Ed] Catmull recognized that his studio’s pixels needed to merge with that world-standard distribution freeway, 35 mm film. Computer chips were not fast enough, nor disks large enough, nor compression sophisticated enough to display even 30 minutes of standard-definition motion pictures. It was axiomatic that for a filmgoing audience to be going to a film, it would be a... film.

Toy Story was a transitional project. Since Pixar couldn’t send digital data to theaters, every one of the movie’s frames was printed on analog film. When Toy Story originally hit home video, that 35 mm version was its source. Only years later, after technology advanced, did Pixar start doing digital transfers — cutting out the middleman. And Toy Story’s look changed with the era.

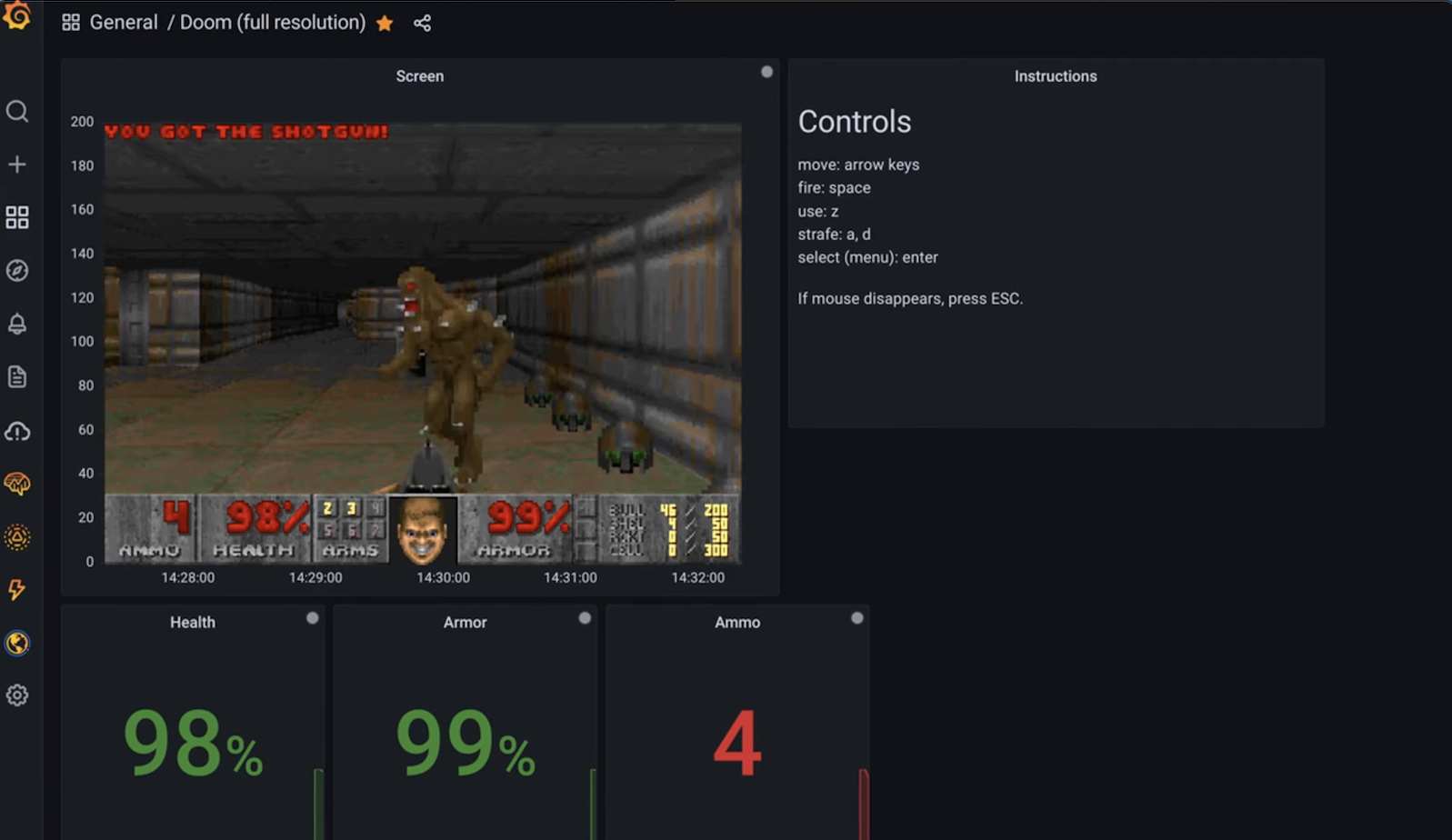

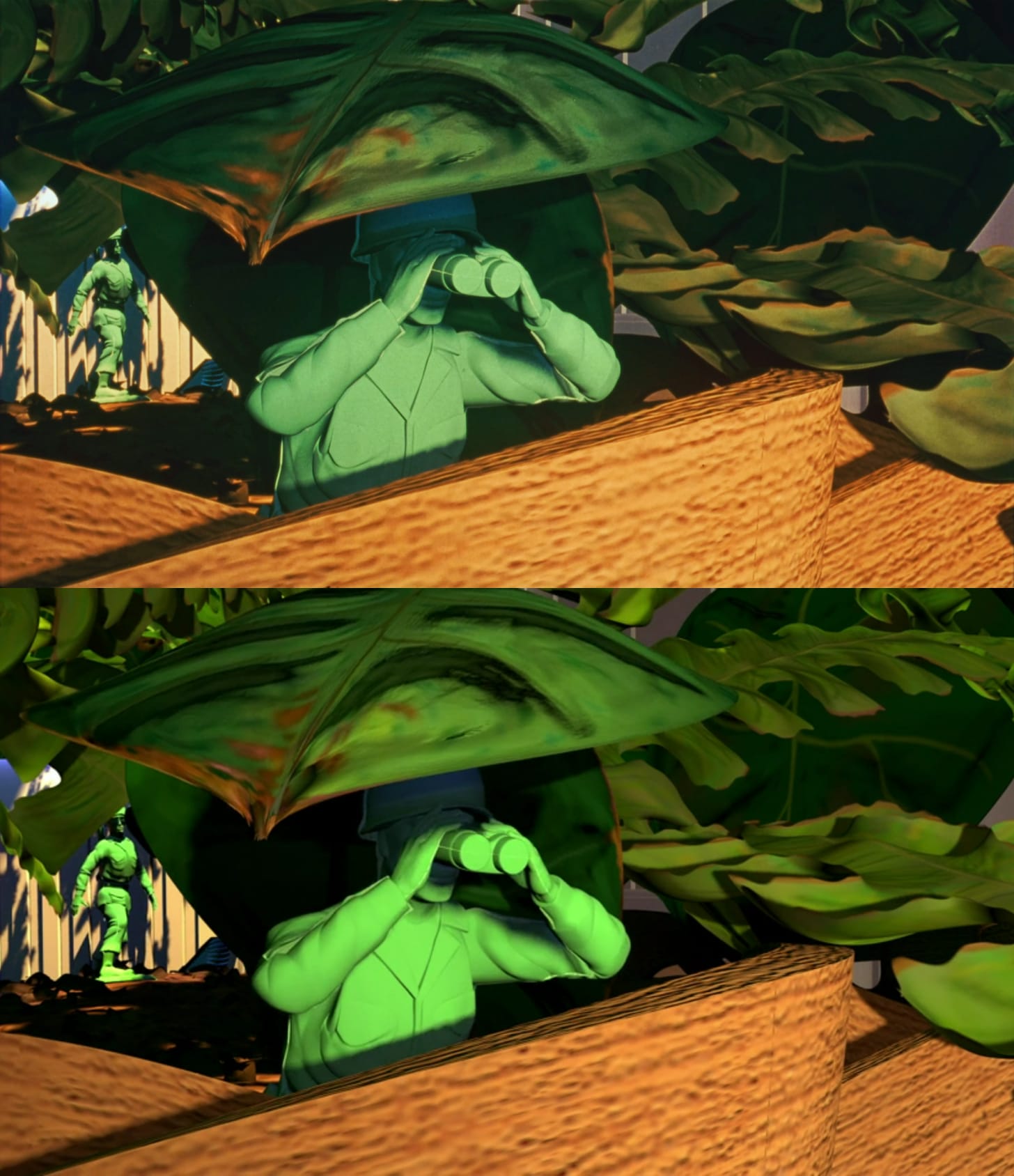

While making Toy Story, Pixar’s team knew that the grain, softness, colors and contrasts of analog film weren’t visible on its monitors. They were different mediums.

So, to get the right look, the studio had to keep that final, physical output in mind. The digital colors were tailored with an awareness that they would change after printing. “Greens go dark really fast, while the reds stay pretty true,” said Toy Story’s art director, Ralph Eggleston. “Blues have to be less saturated to look fully saturated on film, while the oranges look really bad on computer screens, but look really great on film.”

The team checked its work along the way. In the words of Pixar’s William Reeves:

During production, we’re working mostly from computer monitors. We’re rarely seeing the images on film. So, we have five or six extremely high-resolution monitors that have better color and picture quality. We put those in general work areas, so people can go and see how their work looks. Then, when we record, we try to calibrate to the film stock, so the image we have on the monitor looks the same as what we’ll get on film.

Behind the final images was a “painstaking transfer process,” according to the press. Leading it was David DiFrancesco, one of Pixar’s early MVPs, who began working with Ed Catmull before Pixar even existed. He broke ground in film printing — specifically, in putting digital images on analog film.

He and his team in Pixar’s photoscience department used their expertise here. Their tools were “commercial grade” film printers, DiFrancesco noted: modified Solitaire Cine II machines. He’d invented more advanced stuff, but it wasn’t viable for a project of Toy Story’s size. Using the best equipment would’ve taken “several terabytes of data,” he said.

Their system was fairly straightforward. Every frame of Toy Story’s negative was exposed, three times, in front of a CRT screen that displayed the movie. “Since all film and video images are composed of combinations of red, green and blue light, the frame is separated into its discrete red, green and blue elements,” noted the studio. Exposures, filtered through each color, were layered to create each frame.

It reportedly took nine hours to print 30 seconds of Toy Story. But it had to be done: it was the only way to screen the film.

In 1999, Pixar made history again.

Its second feature, A Bug’s Life, reached theaters in 1998. Once more, the studio designed its visuals for analog film (see the trailer on 35 mm). Its people knew the ins-and-outs of this process, down to the amount of detail that film stock could accept and a projector could show. That’s partly how they got away with the movie’s tiny 2048×862 resolution, for example.

Still, the team struggled with one thing: the dip in image quality when film got converted to home video. That’s how Toy Story was released, but there had to be a better way.

For the home version of A Bug’s Life, Pixar devised a method of “go[ing] from our digital image within our system … straight to video,” John Lasseter said. He called it “a real pure version of our movie straight from our computers.” A Bug’s Life became the first digital-to-digital transfer on DVD. Compared to the theatrical release, the look had changed. It was sharp and grainless, and the colors were kind of different.

A digital transfer of Toy Story followed in the early 2000s. And it wasn’t quite the same movie that viewers had seen in the ‘90s. “The colors are vivid and lifelike, [and] not a hint of grain or artifacts can be found,” raved one reviewer. It was a crisp, blazingly bright, digital image now — totally different from the softness, texture and deep, muted warmth of physical film, on which Toy Story was created to be seen.

Quickly, digital transfers became a standard thing. Among others by Pixar, The Incredibles puts off a very different vibe between its theatrical and later releases (see the 35 mm trailer for reference).

Pixar wasn’t the only studio to make the leap, either. Disney did as well.

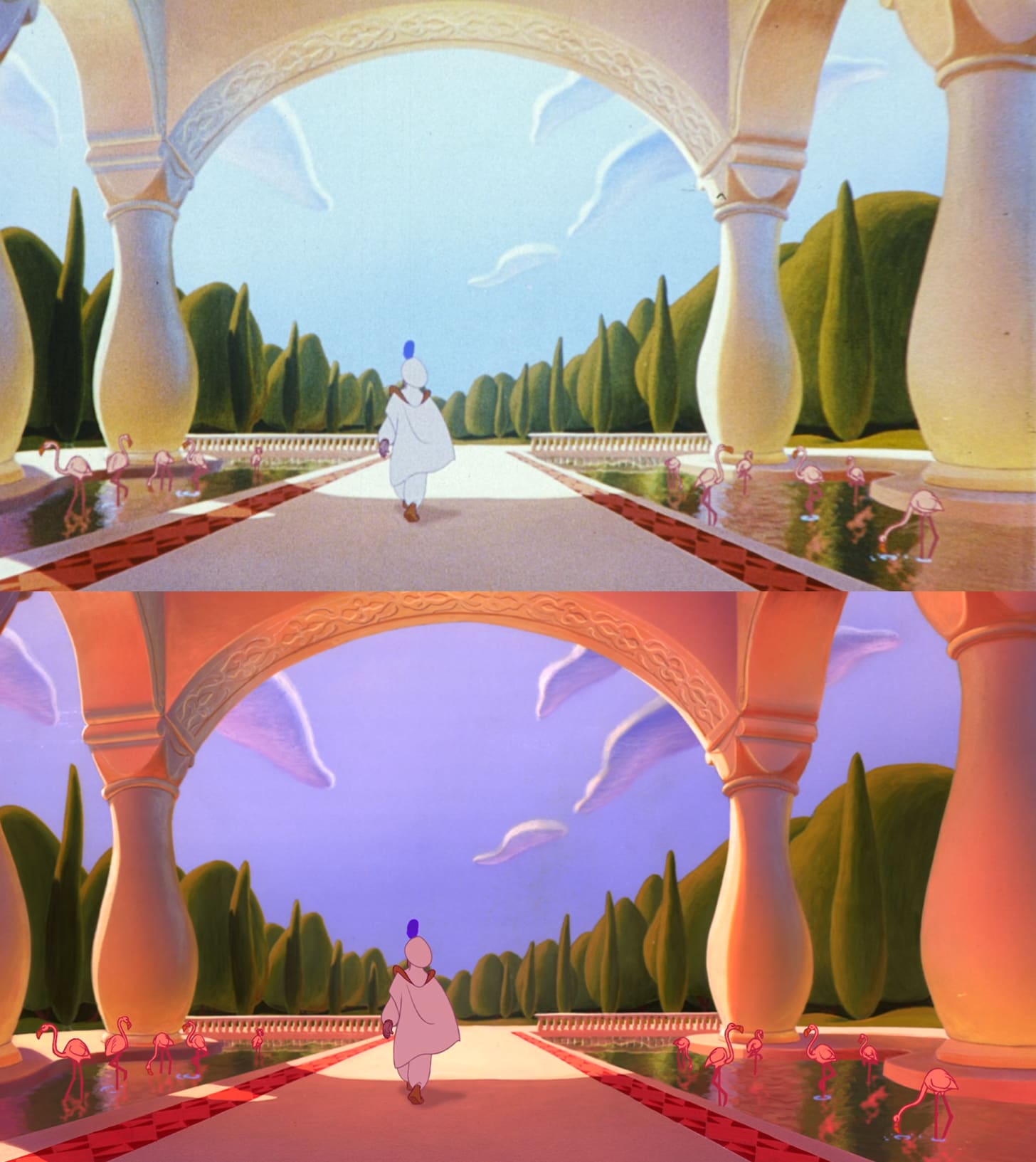

Like Toy Story, the Disney renaissance work of the ‘90s was transitional. The Lion King, Mulan and the rest existed as files in computer systems — and the idea was always to record them on analog film at the end. Early home releases were based on those 35 mm versions. Later releases, like the ones Disney streams today, were direct transfers of the digital data.

At times, especially in the colors, they’re almost unrecognizable. And the images feel less cohesive — like something’s missing that was supposed to bring all the elements together. These aren’t quite the same films that ruled the ‘90s.

For a number of years, there’s been talk in film-preservation circles about Toy Story and the Disney renaissance. This work sits in an odd place. The world was still pretty analog when the computer animation boom arrived: out of necessity, these projects became hybrids of new and old. What’s the right way to see digital movies that were designed for 35 mm film?

The studios themselves haven’t quite figured it out. On Disney+, the colors of Toy Story feel a bit raw — searing greens that were meant to darken on film, for example. Meanwhile, the newer Toy Story Blu-ray shares more in common with the original colors, but it’s still an altered, colder look.

When digital transfers first showed up, people were thrilled, including at Pixar. Movies became “crisper, clearer and more stunning on home video systems” than in theaters, some claimed. Even so, it’s a little disquieting to think that Toy Story, the film that built our current world, is barely available in the form that wowed audiences of the ‘90s. The same goes for many other movies from the transitional era.

The good news is that this conversation gets bigger all the time. In those film-preservation circles, a dedicated few are trying to save the old work. More and more comparison videos are popping up on YouTube. If you get the chance to see one of the old Disney or Pixar films on 35 mm, it’s always worthwhile.

These companies, ultimately, decide how Toy Story looks today. Still, for some, it’s nice to see the original version of the film again — the version Pixar originally intended to make. It’s evidence that the film did feel different back then. The memories were real.

I Am Frankelda continues its strong performance in Mexican theaters. Analyst Edgar Apanco reports that 658,000 people have gone to see it, surpassing the popular Chainsaw Man movie. Revenues are over $2.15 million and climbing — having fallen just 17% in week two, and an estimated 20% in week three.

In Japan, Goro Miyazaki revealed that his father is still going to Studio Ghibli to draw for a few hours each day.

An exhibition in Taiwan brought the films of Karel Zeman to the country, reportedly for the first time. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen and Invention for Destruction are showing, among others.

In Nigeria, animator Gabriel Ugbodaga had a televised interview about his well-received film Vainglorious (watch) and the state of the country’s industry. “When it comes to 2D hand-drawn animation,” he said, “there’s a lot of talent in Nigeria.”

If you missed that Baahubali: The Eternal War teaser this week, see it here. It’s an Indian feature presented by S. S. Rajamouli (RRR).

In Germany, Werner Herzog’s animated film The Twilight World picked up “€100,000 for production preparation support,” reports Cineuropa.

Infinity Castle will reach China next weekend, and forecasters believe it could earn a billion yuan (over $140 million) and become the highest-grossing anime film in the country.

Also happening in China next weekend: the latest edition of Feinaki Beijing Animation Week. The festival posted 55 trailers for its selections this year.

The Japanese journalist Atsushi Matsumoto is raising concerns that the anime boom of the 2020s could be a bubble. (Meanwhile, despite huge industry profits, analysis suggests that studio closures are set to rise for the third year in a row.)

In America, for those in New York, there’s an interesting series of stop-motion screenings at the Eastman Museum this month — including The Wolf House.

Last of all: we wrote about a handful of recent, free films worth seeing.

Until next time!

.png)

![What is a graph database? [video]](https://news.najib.digital/site/assets/img/broken.gif)