Mingyang Smart Energy

Mingyang Smart Energy

China is racing to develop a new generation of wind farms that can not only survive tropical cyclones, but also harness their power.

In southern China's Guangdong province, a new skyline is taking shape away from its shores: hundreds of wind turbines have been installed in the South China Sea to generate renewable electricity for homes, offices and factories.

The enormous towers – some as tall as 30-storey buildings – are a symbol of China's ambition for a greener future. Guangdong, one of the country's offshore wind hubs, is already home to about 15% of all turbines installed in the ocean worldwide. Over the next five years, the local government plans to more than double that fleet.

These turbines are on the frontline of one of the most destructive weather phenomena on Earth, which hits China's coast year after year: typhoons, tropical cyclones originating in the northwest Pacific.

These powerful storms bring winds at speeds of 119km/h (74mph) or higher. They terrorise East and Southeast Asian countries every May to November, and often leave a trail of death and destruction, including collapsed buildings and flooded streets. Typhoon Ragasa, which devastated southern China in September and was the world's most powerful storm this year, reached speeds of 241km/h (150mph). Typhoons are the same phenomenon as hurricanes: they are both spinning storms fed by warm air, and just go by different names depending on where they occur. If they originate in the North Atlantic and northeast Pacific, they are called hurricanes; in the northwest Pacific, they are called typhoons.

Getty Images

Getty Images

However, the swathes of China's coastal regions that face typhoons multiple times a year, also have the best offshore wind resources, says Zhu Ronghua, director of Yangjiang Offshore Wind Energy Laboratory, an institute supported by the Guangdong government. The challenge, he says, is to build wind farms that are able to reap the typhoon's energy.

"It is extremely important that turbines installed in those regions can not only resist typhoons, but also harness the strong gusts in the lead up to their arrival," Zhu says.

Chinese companies are at the forefront of the research, development and commercial deployment of typhoon-resistant wind turbines, says Qiao Liming, who at the time of the interview was chief strategy officer for Asia at Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), a global trade body for the wind power sector.

"The Chinese government has made a strategic decision to make offshore wind a cornerstone of its 'dual‑carbon' goals," Qiao says. The goals refer to peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality before 2060.

The battle with nature

There are different ways to define a typhoon-resistant turbine. Nationally speaking, China has a standard that guides companies to make "typhoon-type" turbines capable of withstanding wind averaging up to 198 km/h (123mph) for 10 minutes.

On a global level, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) – an organisation publishing international standards for electrical, electronic and related technologies – has developed guidelines for "typhoon-class" turbines expected to survive 205 km/h (127mph) wind for 10 minutes and gusts of up to 290 km/h (180mph) for three seconds.

Neither is mandatory, but manufacturers can have their products certified by a third-party company to meet these standards. Some turbines in China do not have those certificates but have survived typhoons, so they become typhoon-resistant by reality, according to industry experts.

On average, a Chinese offshore wind farm is hit by at least 100 typhoons during its lifespan

On average, a Chinese offshore wind farm is projected to experience at least 100 typhoons during its designed lifespan, which is normally 25 years, according to a spokesperson at Goldwind, a Chinese wind turbine manufacturer.

"If a wind turbine collapses, it can threaten human lives and cause enormous financial losses," the spokesperson says.

Past disasters have shown the severity of damage. In 2006, super typhoon Saomei landed in east China's Zhejiang province, bringing gusts up to 245 km/h (152mph). It destroyed 27 turbines at an onshore wind farm, of which five collapsed. The incident alone caused a staggering $70m (£52m) in economic losses.

Getty Images

Getty Images

During a typhoon, every part of a turbine is put under extreme pressure. Its blades are vulnerable to fracturing, cracking and breaking because the speed and direction of wind often change suddenly and dramatically. Its tower can bend or collapse, and its foundation – which also has to take the pressure from surging waves and fast ocean currents – is at risk of becoming deformed or overturning. Rain and lightning strikes can damage turbines, too.

When a typhoon approaches, a wind farm often shuts down its turbines through a remote-control system once the wind speed reaches their operational limits, according to Han Yujia, a renewable energy researcher at Global Energy Monitor (GEM), a California-based non-profit. Many turbines are also capable of turning themselves off automatically, she says. The turbines are then powered by their internal diesel generators or batteries. A control system enables them to make real-time reactions – such as changing the direction they face or altering the angles of their blades – to minimise the typhoon's impact, Han notes.

Both on-land and offshore wind turbines need to be typhoon-resistant if they are installed in areas exposed to the weather phenomenon, but the feature plays a more crucial role for offshore ones because typhoons are much stronger at sea, says Xiaoli Guo Larsén, a professor at the department of wind and energy systems at the Technical University of Denmark.

Standing tall

Major Chinese companies have increased their turbines' resilience using a combination of strategies, according to Han. They include developing advanced materials, improving their weather-forecasting ability and upgrading turbines' control systems, she says.

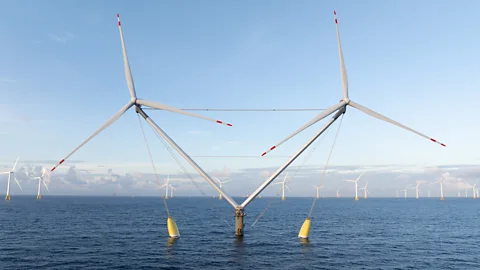

A good example, according to Han, is a model called OceanX manufactured by China's Mingyang Smart Energy Group.

With a floating foundation, the OceanX model supports not just one but two turbines. The main reason behind the unique design is to increase the platform's output. Compared to a single turbine whose blades swipe across the same area as OceanX's two turbines combined, OceanX can generate 4.29% more electricity, according to Mingyang. This is because the two turbines' blades spin side by side in opposite directions – one clockwise and the other anti-clockwise – so the wind between them will blow faster, enabling more electrical energy to be converted from air kinetic energy, the company says.

But the floating platform also has plenty of intriguing features to counter typhoons and stay balanced during extreme weather, says Wang Chao, the turbine's chief designer. For example, its foundation is tied to the bottom of the ocean by ropes via one single point underneath it. This allows the structure to change its orientation more easily to be aligned with the wind. "As long as the turbines face the typhoon, the load (forces) they take will be the smallest and they will be the safest," Wang says.

Another feature is the "ultra-high performance" concrete used to build OceanX's foundation. It is four times tougher than normal concrete and can withstand pressure exceeding 115 Megapascal – that's more than 16,600lb (7,530kg) per square inch – according to Wang.

In September 2024, the model was installed in a wind farm about 70km (43 miles) off the coast of Yangjiang city in Guangdong, just a few weeks before super typhoon Yagi – the strongest typhoon China had seen in a decade – slammed into the country's southern coastlines.

OceanX was situated in a patch of waters that saw its wind speeds reaching up to 133 km/h (83mph), and it successfully braved the gales and waves, Wang says.

Mingyang OceanX

Mingyang OceanX

Closer to one of Yagi's landing sites, 47 wind turbines manufactured by Goldwind withstood maximum wind speed of 161 km/h (100 mph) for six hours off the coast of Guangdong's Xuwen county, according to the company's spokesperson. Those turbines also managed to generate a total of 2.1 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of power in the space of nine hours when Yagi passed the region, the spokesperson said. That amount of electricity can power more than 2,100 Chinese citizens or nearly 800 UK families of three for a year.

A wind farm in southern China managed to generate enough electricity to power more than 2,100 citizens for a year as a typhoon passed

Goldwind achieved the feat via a series of innovations, its spokesperson says, including by using stronger materials such as carbon fibre and an advanced monitoring system that helps the wind farms' staff access the turbines' status in real time so as to make the best decisions.

Some researchers say it is important that offshore turbines can capture typhoons' gusts as long as it is safe to do so. Otherwise, a turbine will have to be turned off when the wind speed exceeds 88km/h (55mph) – the average "cut-out" speed for turbines – says Zhang Mengqi, another researcher at GEM. "Then a huge amount of clean energy will be wasted," she notes.

Snapped towers

Tropical cyclones form on the warmer ocean near the equator and typically travel westwards and towards the poles, so they rarely hit Europe – though the continent is facing more and more intense storms. The United States is yet to build offshore wind farms on a large scale in its hurricane-prone regions in the south, Zhu says.

"China may have the most advanced typhoon-resistant technologies for wind turbines right now," he adds.

More like this:

• Riders on the storm: The birds that fly into hurricanes

• How climate change is rewriting the rules of extreme storms

• These Florida domed homes survived category-5 hurricanes

The technology has a huge home market. Over the next decade, about 170 GW of new offshore wind capacity – more than twice the global total offshore wind capacity currently – will be connected to the grid in China, and about 60% of them will be located in typhoon-prone regions, according to Wang Yufan, an analyst at research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

But major accidents still happen. During Yagi, a seaside wind farm in Hainan's city Wenchang was severely damaged by the super typhoon when it landed in the city, bringing gusts as strong as 223 km/h (139mph). (Yagi made a total of four landfalls in East and Southeast Asia.) Photos of the aftermath show the wreckage of around seven broken turbines on a beach, and all their towers are snapped.

Multiple researchers tell the BBC that those turbines had just been installed and not been connected to power, so they could not make necessary adjustments during Yagi to protect themselves.

Most recently, typhoon Ragasa tore through southern China in late September, forcing more than 2.2 million people to be evacuated in Guangdong province, according to China's state-run agency Xinhua. In Yangjiang, where Ragasa landed, the local government moved 167,343 people to safety and opened the city's 1,038 shelters to residents, Xinhua reported.

While it is too early to fully assess the impact of this latest typhoon, at least five wind turbines in Yangjiang collapsed, according to journalists reporting from the city for Chinese publications Red Star News and Cover News. The natural disaster, which lasted three days, could cause up to 468 million yuan ($66m) in economic losses for offshore wind farms in China under the worst-case scenario, according to projections made by China Property and Casualty Reinsurance Company, a Beijing-based insurance company, before Ragasa's landfall.

OceanX withstood maximum wind speed of 152 km/h (94mph) as Ragasa passed, Wang says. According to Mingyang, the typhoon affected the company's 1,345 offshore wind turbines in three provinces, and all of them coped well.

A team of experts in Goldwind had projected Ragasa's pathway five days before it landed using a self-developed early-warning system, and created a typhoon-countering plan for each of the company's wind turbines affected by the event, according to the company’s spokesperson.

The pre-emptive strategy helped Goldwind's more than 260 offshore turbines successfully survive the event, including when the wind speeds suddenly increased from 68-144 km/h (42-89mph) within a few hours and the wind direction shifted by 150 degrees within 15 minutes on 24 September, the spokesperson said.

NOAA via Getty Images

NOAA via Getty Images

'Palm-tree' turbines

As interest in offshore wind energy grows, so do challenges. For one, it is becoming harder to keep turbines safe as the blades become longer and longer.

One potential solution is to use "downwind" blades – meaning, blades placed behind the motor, rather than in front – to protect the turbine, according to a project by several US universities.

Conventional "upwind" blades are placed in front of the motor to face into the wind. When attached that way, the long blades must be stiff enough so as not to curve backwards in strong winds and strike the tower while spinning, says Lucy Pao, a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who participated in the project between 2016 and 2022. However, making them that stiff usually requires expensive materials, she says.

The alternative, "downwind" blades proposed by Pao and her colleagues were inspired by flexible but resilient palm trees and could be made with more cost-effective materials. They are fixed behind the motor facing away from the wind, and can fold up to deflect gusts. (Mingyang's OceanX turbines have downwind blades but they cannot fold.)

Another problem is the "rapid intensification" of typhoons, which means they are getting more intense over a shorter period of time, Han says. A 2023 paper found that the number of typhoons that rapidly intensified per year in offshore areas within 400km (249 miles) from the coastline tripled between 1980 and 2020 due to climate change. Wind farms and turbine manufacturers must design better strategies to respond to the trend, she says. Han also thinks that manufacturers should make swappable parts for offshore turbines so they can be fixed more easily after sustaining damage.

Nevertheless, many consider China's vast experience in building typhoon-resistant turbines valuable for other regions, such as Southeast Asia, which is keen to harness their offshore wind but also faces the annual blasts.

There are also challenges, GWEC's Qiao warns. Each wind power project must consider site-specific wind conditions so as to select appropriate turbine models, she says. Plus, many typhoon-prone areas in Asia are remote islands with weak grids and different power standards, so those wind power projects must be carefully considered, she adds.

But the experts also see the offshore wind industry's ongoing battle with nature as a fascinating engineering challenge.

"Tropical cyclones are a challenge for developing wind power because they can be very destructive," Larsén says. "But they also provide an opportunity for humans to use new technologies to develop the ultimate turbines that can withstand the toughest conditions."

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

.png)