Three attempts at making payments secure

Written by Jay on July 16, 2025.

In the early 1990s, three companies pioneered online transactions, facing challenges of security and user accessibility. They are hardly known today.

This is part two of a series on e-commerce. Read part 1 here.

In the first few years of the web, it wasn’t strictly legal to sell things over the Internet. Restrictions on the government funded ARPANET lingered, limiting its commercial use. Certain companies began experimenting on the fringes, securing government contracts as a way to provide some basic legal cover in doing so.

The sea change was in 1993, when the government handed off Internet service to commercial telecom companies, like AT&T and Sprint and updated its acceptable usage policy to include commercial traffic. Overnight, the Internet became a place of business. And the possibility of commerce online changed everything.

In August of 1994, less than a year after that change, three completely different approaches to securing the commercial web were launched to public. All in the same month. The biggest challenge ahead of them was making transactions on the web secure. Each company had a different approach, hoping to create as little friction for their customers as possible.

Over then next couple of years, those companies would compete and vie for the future of the commercial web. In the end, it’s unlikely you’ve heard of any of them. This is what they tried.

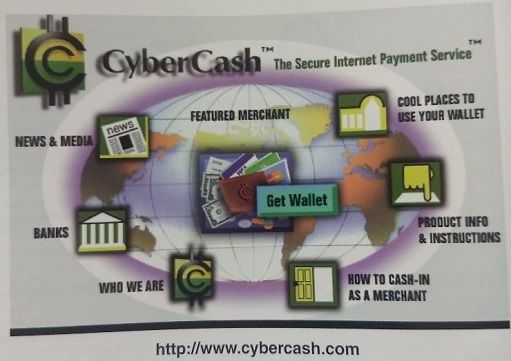

CyberCash: Bolting on to the web

Dan Lynch and Steve Crocker, already veterans of Internet technology in the early 1990’s, decided to go down to the level of the operating system. They helped found Cybercash, a collection of software for making transactions across the Internet more secure.

Their flagship product was called Wallet. Online shoppers could download the software and store encrypted credit card information, right on their hard drive. Sellers could then use that encrypted file to process transactions through Cybercash’s server software, CashRegister, without ever needing to read the credit card number itself.

The promise of Wallet was that, after an initial setup, it worked automatically across the web. As people moved around the web buying things, it would handle everything securely directly from their computer. When properly set up and configured, it delivered on that promise. It was an elegant enough solution, that bypassed the problem of insecure web protocols entirely by creating a connection between servers and its own software.

But CyberCash also had to spend a lot of its early energy explaining to customers what its software did, why it was secure, and how to install it. People were somewhat reticent to fully hand over their transactions to some outside service.

Still, Cybercash found success with early adopters and a tech-savvy audience. And even more success among two very specific types of businesses, pornography and gambling. These sites were looking for ways to give customers an anonymous experience that was secure enough for regular use and simple enough that it could drive impulse purchases. When these businesses first came online, they tried managing purchases through 900 numbers, or third party sites. Even with the setup time, Cybercash was far easier to use for these sites, and assured its customers that personal data was not being collected. (Years later, this would be the basis for a political scandal in a Virginia gubernatorial race).

Cybercash also became the first company to try micropayments, notoriously hard to process because of how small the amounts typically are. For transactions under $10, they introduced a product called Cybercoin. People could prepay and buy packages of “coins” directly from the company. This money would be held in a proxy escrow account, separate from both buyers and merchants, which could then be used for small paments, amounting to $10, $1 or less.

This early adoption in certain industries, combined with innovations like these, was enough to propel the company to some early success. They expanded into more credit card processing capabilities, and even worked on a potential Internet spec for credit card transactions. But a series of wrong turns in the first few months of 2000 led to a potential hack and a bonafide Y2K bug. It was all too much, and the company filed for bankruptcy in 2001.

NetMarket: Building a new Browser

NetMarket was the brainchild of Dan Kohn, an American college student who had discovered the web while studying at a one year program in London. He registered the domain name for NetMarket.com before he even returned home. Once he did, he and a few friends rented a house together in New Hampshire with the sole purpose of figuring out how to provide a proper online shopping experience.

Even at the beginning, Kohn was primarily driven by curiosity. He wanted to use the web as a way to expand real life experiences all over the world. It’s something he would take with him for the rest of his career, helping open source and public health communities.

The biggest hump wasn’t building the website, or even finding retailers willing to sell things online. HTML and server technologies were easy enough to learn, and they had managed to find a local music store down to try selling things on the web on a homegrown site the Netmarket team had put together. Their challenge was in making the web secure.

In the early 1990’s, Phil Zimmerman developed an encryption program called Pretty Good Privacy, or PGP. Because of it’s use of the still relatively new public key cryptography, it’s source code was freely available. Same with the X-Mosaic browser being developed at NCSA. So the NetMarket team created their own browser by combining the two, merging X-Mosaic with PGP to create a browser with built-in secure transactions.

If you wanted to buy something from NetMarket, you had to download their tailor made browser. At the time, that wasn’t necessarily an easy task. For one thing, the software only worked on Unix machines, and it had to have PGP set up and configured properly. The first person to buy something from the site, an old college friend, called Kohn up personally to try and get everything set up just right. But once he did, he purchased a Sting CD from NetMarket, fully securely, in August of 1994. And NetMarket went down as one of the first secure transactions on the web.

via Web Design Musuem

via Web Design MusuemEven though the browser setup was somewhat unwieldy, some of those small early transactions got the word out. Within the next few months, the site was acquired by a large membership services company, Comp-U-Card International (who would later be embroiled in a major financial scandal) who began rapidly expanding the service.

The next few iterations of the site embraced a vision of being a web-based mall. A one stop shop to get anything you might need. In a partnership with AOL, they moved their mall to a more closed network and largely tied up their future with them. In the end, they spread themselves too thin, and couldn’t keep up. The site continued to evolve, but eventually faded away.

Internet Shopping Network: Finding a Protocol

CyberCash and NetMarket struggled with the same issue. Most web users didn’t have the desire or the knowhow to go install that kind of software. Longtime tech entrepreneur Marty Tenenbaum understood that. Early in the 1990’s, he envisioned a web that is much like what we have today—where people do most of their shopping online and retailers reinvent themselves to match new exepctations of their customers.

Tenenbaum pulled together a group of researchers and computer scientists and founded EIT with the goal of finding a secure solution for web commerce that was entirely invisible to end users. Security by default, and available in all web browsers, added to the technology of the Internet itself. Among the team at EIT were security experts Allan Schiffman and Eric Rescorla, web designer Kevin Hughes, and for a brief stint at the organization’s founding, Mosaic creator and later Netscape founder Marc Andreessen.

Rescorla and Schiffman began looking at the technology itself, working on ways to make browsing the web more secure. Their solution added encryption to the HTTP protocol itself, meaning that it could work with any browser, and make any website secure. They called it, somewhat straightforwardly, Secure HTTP, or S-HTTP.

Like CyberCash and NetMarket, it made use of public key cryptography to create a secure handshake between the browser and the server and verify that traffic was secure. However, their solution had a marked difference. Because it worked across HTTP itself, it didn’t require special software. It was a part of the web itself.

Tenenbaum also knew that he had to prove out what shopping online really felt like as well. To that end, Tenebaum helped put together CommerceNet, a consortium of small businesses, suppliers and software makers aimed at understanding and promoting commerce on the web. Several businesses and corporations began exploring S-HTTP, backing the technology, and integrating it into some early experiments.

Back at EIT, Tenebaum’s team worked on the small interactions that would be visible to people buying things across the web. This is where Marc Andresseen, fresh off his work creating Mosaic and brand new to Silicon Valley, got involved. His time at EIT didn’t last long, and involved a lot of friction, but he helped them think through what securely browsing online looked like to end users. Kevin Hughes brought this to life, creating the first true design language for security, one that would be familiar to most web users today. The green lock, the signed transaction, the envelope, all paired with small animations that indicated to web surfers that what they were doing was signed, secured, and delivered.

EIT also helped launch a new site called Internet Shopping Network that made use of S-HTTP built into the web and Mosaic. It served as a proof of concept for how everything would actually come together. The site began by selling computer parts, but quickly moved to new options, expanding to include many more options. It would eventually sell to Home Shopping Network.

An early iteration of the Internet Shopping Network, via Valerian Mayega

An early iteration of the Internet Shopping Network, via Valerian MayegaInternet Shopping Network, like the other sites and products listed here, launched in August of 1994. Within a year, CommerceNet released a survey in partnership with Nielsen that claimed nearly 20 million people were using the World Wide Web regularly, and that 2.5 million people had already purchased something on the Internet. That study quickly came under fire, however, for selecting a sample size that leaned towards affluent technology users which skewed the results.

CommerceNet was forced to deal with the fallout of that survey. And at the same time, a new threat to S-HTTP surfaced from EIT’s former employee Marc Andreessen. He had gathered a team at Netscape and used his insights from EIT to develop an alternative to their technology, known as SSL.

.png)