One of the great pleasures of hanging around old institutions like Harvard or Princeton or even Johns Hopkins (new-ish, at 1876) is sitting in halls that feature bas-relief portraits of prominent figures. When a lecture becomes boring (yes this happens) you can ponder the art. I’ve spent many hours in my life pondering bas-relief.

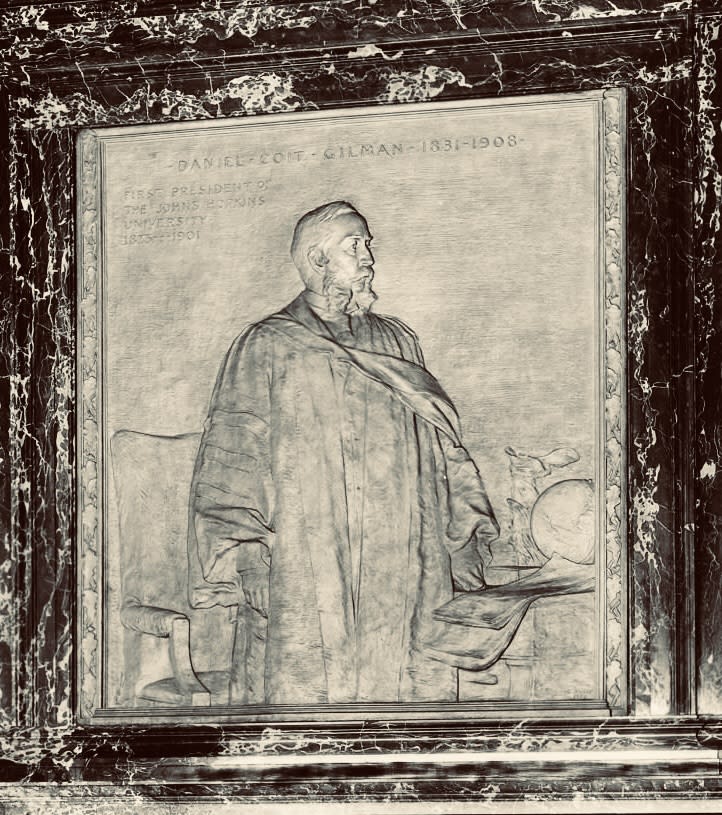

Here’s one of Daniel Coit Gilman, the great founding president of Johns Hopkins University, though this isn’t the one that provoked this essay. I’ve spent many hours looking at it.

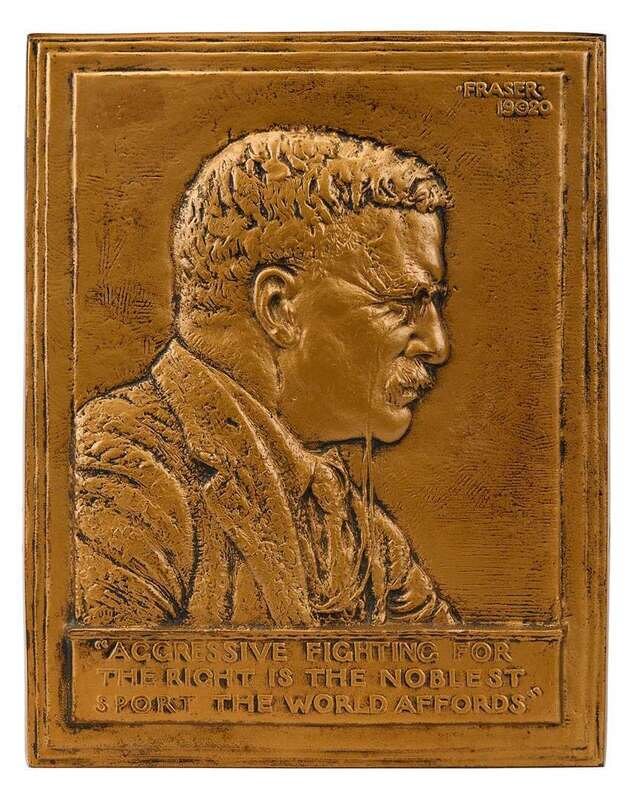

Here’s another, the famous 1920 bronze bas-relief of Theodore Roosevelt by James Earle Fraser.

With bas-relief, the figure seems to exist within the surface, pushed out from the material itself. It is half there, more than an image, less than a sculpture. The wall suddenly decides to be face-like, person-like.

Why did this form of art drop out of cultural favor?

Well, bas-relief exists in a funny middle state. It is a representation, of course. That’s a face; you recognize it as a face. The figures are wearing clothes. It is also just a surface with different heights. The face is made of the same stuff as the wall, the setting around it. It isn’t separated into an independent thing. I have spent hours looking at the Gilman bas-relief as if the wall itself were trying out personhood.

There’s a tension in bas-relief that I like. If the goal is to create art that represents, why go only halfway? Make a painting that creates a full illusionistic space, or a sculpture that exists completely in three dimensions. If the goal is to transform material into representation, why leave it half-attached to its ground? And if the goal is art that celebrates the material itself, why force it into the shape of a face at all?

Bas-relief is stuck between representation and material presence. The face is recognizable and also the material doing something. You can’t forget the surface, and you can’t ignore the face.

Here’s one of my favorite bas-reliefs: Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, which I visited last month. (Fraser apprenticed with Saint-Gaudens.) There is Colonel Robert Gould Shaw on horseback leading the Black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment as they marched down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863. Saint-Gaudens worked on it longer than any of his other works. The Shaw family didn’t want a traditional equestrian statue because Shaw was a scholar first and only a military commander by happenstance. The flattened form brought Shaw and his men onto the same plane. They are all bound together, emerging from the background collectively.

It’s a beautiful piece. But like all bas-relief it doesn’t want you to ask too many questions.

By the mid-20th century, there were new demands for clarity, for a purity of form, in art. Either make images or make objects. Either represent or present. Bas-relief, doing both and neither, was seen as formally confused, theoretically incoherent. Artists wanted problems that hadn’t been solved yet, forms that didn’t already know what they were. Bas-relief portrait medallions were conventional, safe, academic, competent at best. You see the form now mostly in official architecture, monuments, and medals, where symbolism is the point, not aesthetic innovation.

Remember coins? Everyone used to have them in their pockets, even just a few years ago. They are all bas-relief. Almost every coin you’ve ever held has a face emerging from metal: Washington, Lincoln, the Queen. The face comes out of the metal, rises from it. The metal has organized itself into a face shape. You used to pay for coffee with a disc of metal that had thrust up a human profile from its surface. The metal disc means a quarter because Washington emerges from it. No Washington, just worthless metal. The representation creates the value, and the representation only works because it’s dimensional, because it’s the material itself transformed.

The face turns metal into a token. The word ‘token’ originates from the Old English tācn, meaning a sign, symbol, or evidence. Tokens were a transformation, a physical object given as proof of something, a coin-like disc, a medal you could hold and exchange. The material becomes exchangeable because it carries this emergent image. Bas-relief is the technology that makes tokens possible. You need dimensional difference to prevent counterfeiting, to create something feelable, verifiable by touch. Flat printing can be copied. Dimensional difference requires the metal to remember being organized, to hold the shape.

You see where I’m going with tokens, the thing that stands in for another thing. In the modern material world of my lifetime, before “tap” payments or MetroCards, a token was a stamped piece of metal to pay for a subway ride. More generally a token is a discrete, physical unit that carries specific meaning within a given system.

Artificial intelligence uses the same word to manage unstable human language. An AI model can’t process a sentence as a continuous flow of meaning. It breaks language down into discrete, countable units called tokens, which it can analyze mathematically. Each token is converted into a string of numbers (a vector), turning language into a mathematical problem. As this NVIDIA “explaining tokens” site explains:

The word darkness, for example, would be split into two tokens, “dark” and “ness,” with each token bearing a numerical representation, such as 217 and 655. The opposite word, brightness, would similarly be split into “bright” and “ness,” with corresponding numerical representations of 491 and 655.

The term had first been adopted by computer scientists in the late 1950s and early 1960s who were designing compilers to translate human-readable code into machine code. The first step of this translation process, lexical analysis or “lexing,” grouped raw text into units they called tokens.

Decades later, natural-language systems and large language models kept the same logic. Models such as GPT-3 use a kind of subword tokenization, often based on a method called Byte-Pair Encoding. This system breaks words into common pieces so the model can handle any word by combining familiar parts, turning human language into a finite set of calculable units. Later models, including GPT-4 and GPT-4o, follow the same approach, though with larger vocabularies, longer context windows, and new encoding schemes. The token remains the basic operational unit, the measurable fragment of meaning.

There’s a way that the word ‘token’ remembers its origin as a coin while describing something that feels completely abstract. You pay for AI by the token, literally purchasing these units of generated meaning.

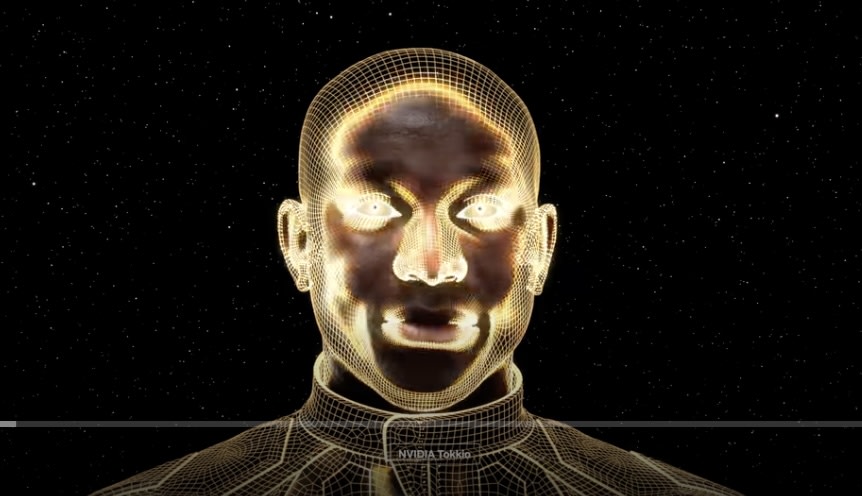

The NVIDIA explainer site doesn’t refer to term’s history as a coin or its original materiality except for the first sentence: “Under the hood of every AI application are algorithms that churn through data in their own language, one based on a vocabulary of tokens.” There’s a video called “The AI Factory” you can watch. At :29 it shows a face emerging from the background like a bronze bas-relief.

“Tokens transform words into knowledge,” the face says, “and breathe life into images.”

It’s a lovely video (with uplifting music) but the phrase “under the hood” makes one pause. As if by looking beneath the surface you’ll understand how it all works.

There is no hood, of course. And even if there were, what would you find? Tokens. Which are themselves made of other tokens. Which process tokens to generate tokens. It’s tokens all the way down, with AI.

If you had a quarter in your pocket right now, this is the time to touch it, to remind yourself that the surface doing the thing it is doing is what creates meaning.

Marx has a whole book about money standing between you and the labor that produced whatever you’re buying, between you and the web of social relations that makes the transaction possible.

NVIDIA’s “under the hood are tokens” is doing something weirder even than Marx. Look under the hood, they invite you, and you’ll understand what AI can do, the social relations going forward: the weather forecasting, the medical breakthroughs, the helping people walk and talk again. All good! But still invisible are the social relations that produced the tokens: the training data, the labor that produced it, the decisions embedded in the model, the infrastructure running it. Those faces don’t appear on any token.

The final trick of the faceless series of tokens is to convince you there is a “hood” to look under at all. There isn’t.

And yet, does it matter?

.png)