H is an AI engineer at one of China's largest tech companies, leading an open-source project. A few weeks ago, I met him in Shenzhen during a self-organized "China AI/tech tour" with several US tech writers. After peppering him with questions—the most obvious one being "What's Silicon Valley's biggest misunderstanding about China's AI?"—I discovered someone so thoughtful and genuinely bilingual.

His daily routine reveals the paradox: wake up, doomscroll X, debate on LessWrong, drive his NIO to work, then use English more heavily than when he studied in California. He loves watching Westworld and treats Gödel, Escher, Bach as AI scripture. Apart from geography, H could be any engineer at Anthropic or Google. He represents the global open-source AI community: following identical cultural patterns, reading the same viral posts, grappling with the same technical problems, laughing at the same memes. He just happens to work in China.

"'Chinese AI' is merely a geopolitical label," H said. "All LLMs fundamentally compress and regenerate collected data." Yet despite this universalist perspective, he articulately mapped the profound topological differences between Chinese and American AI ecosystems while understanding the China model's essence with surgical precision.

I knew I needed to extract everything from his brain, so I scheduled a three-hour follow-up call.

That conversation proved illuminating. H, who spent a decade at major Chinese tech companies before focusing on open-source AI, clearly outlined China's AI topology. His grasp of global trends provided grounded insight into who China's AI practitioners actually are and the mental frameworks shaping their decisions.

H cannot publicly disclose his company or name, but what I know: he's discerning, works harder than anyone I've met in Silicon Valley, thinks internationally while harboring grand idealistic tech visions, and remains deeply rooted in China. I assume countless versions of H exist throughout the country.

Below, we explore the following topics of China's AI world:

America's Greatest Misunderstanding: Underestimating China's Below-the-Iceberg Deep Infrastructure and Equating Innovation with Theft

China's Misconceptions About America: Hubris, Overplaying Silicon Valley Setbacks, and Underestimating Valley Talent Depth

Chinese AI's Topology: Seven Circles and Their Interconnected Coupling

Why Jensen Huang Doesn't Need Certain Meetings: Industrial Depth and Collaborative Consensus

Founder Archetypes: From Internet Opportunists to Mission-Driven Technologists

A Peek at Beijing AI Circle: Information Brokers

State Strategy Meets Tech Reality: How Policy Shapes China's AI Evolution

Over-Hype and Underestimated Directions

China's AI Moat: "Cluster Competition" vs. America's "Oligarch Leadership"

Digital Cosmopolitanism: A Chinese Engineer's Journey from X to LessWrong to Russian AI Influencers

Is Zhihu China's LessWrong?

China's AGI "Faith Gap"

A note: Using AI to transcribe conversations is insufficient. I practice "deep contextual translation"—spending hours editing, restructuring, and researching to preserve not just words but cognitive frameworks. Treat this as a thoughtfully edited article rather than a mere transcript.

If you're curious about how the Chinese state relates to AI companies—a dynamic that can puzzle outside observers—the section "State Strategy Meets Market Reality" might offer some useful perspective. This conversation represents one attempt to bridge the cognitive gap between American and Chinese tech communities, though with all the limitations that come from a single voice and finite time. I hope you enjoy it.

Afra: Recently I went to several AI events in Beijing, my investor friend Du Lei made a sharp observation: the AI ecosystems of America and China have fundamentally different topologies. This structural lens reveals profound insights. I find "topology" especially apt—I've witnessed many phenomena in AI that stem precisely from these US-China structural differences.

These differences breed mutual misunderstandings, largely because Chinese information doesn't flow systematically to America. What's the biggest misunderstanding?

H: I think there are two major misconceptions. Let me start with the more fundamental one.

The first is actually a shared blind spot on both sides. Americans assume engineers are roughly equivalent across countries, but there's an enormous underwater portion of China's iceberg that even industry insiders overlook: China’s extraordinarily large pool of well-trained engineers—not just AI engineers, but the entire technical workforce.

Think about what AI actually requires. You need massive infrastructure below the waterline, like an iceberg's hidden mass. This infrastructure demands extensive skilled labor: fiber optic installation, data center construction, network engineering, systems administration—the entire chain from physical infrastructure to model deployment. In China, this workforce is highly systematized and enormous in scale.

Here's what's often missed: if you compare surface teams—DeepSeek's algorithmic group or Qwen's core team, maybe 100-200 people each—they look similar to OpenAI or Anthropic's teams. The real difference lies in that massive underlying foundation. China's talent reserves at the infrastructure level dwarf North America's. It's this deep technical workforce that enables rapid AI deployment and iteration.

The second misconception is more visible but equally damaging: "all Chinese innovation relies on theft." After DeepSeek's breakthrough, or with companies like Zhipu, you see what we jokingly call American Copeism on X. The narrative claims Chinese AI is distilled through illegitimate means.

I used to enjoy

, an AI engineer podcast hosted by swyx. But even sophisticated voices in the community sometimes echo this copeism narrative. When you categorize genuine engineering work by Chinese teams as theft, it actually harms American AI development too. You're essentially refusing to learn from real innovations because they don't fit your preconceptions.

This misconception is particularly damaging because it creates a feedback loop of ignorance. Instead of studying what Chinese teams are actually doing—their optimization techniques, their training methodologies—you dismiss it as stolen, missing opportunities for your own advancement.

Afra: I agree with what you're saying, but how do China's infrastructure advantages and resources translate into AI development advantages?

H: One is efficiency—a crucial metric.

Take Elon Musk building large clusters in Texas. He bought a huge plot of land and had to rely on his own efforts to drive engineering progress. Why does Musk need to live at the factory or personally supervise on-site? Because he must ensure his team can execute his vision. In contrast, Chinese bosses are fortunate—they simply need to tap into sufficient resources without worrying about the nitty-gritty. From construction management to building AI data centers to planning, the personnel are all highly professional. Your presence on-site basically creates disruption because the entire system is already highly segmented, specialized, and systematized. In China, you don't need to worry about these details.

Afra: Precisely. Why must Musk personally battle each bottleneck? He bypasses hierarchies, allowing direct reports across levels. This echoes another infrastructure obsessive in my mind, Geng Yanbo, the former mayor of Datong, a third-tier city in China. I wrote about how this "Datong Musk" transformed the urban landscapes in the most “engineering state” way, borrowing Dan Wang’s framework in his new book Breakneck. Mayor Geng operated like Musk—visiting construction sites, unblocking obstacles. He'd ask electricians directly: "Why no power today? Who's blocking you?" Then solve it immediately. Pure Musk methodology at SpaceX and Tesla.

Your point about China's workforce and specialization also recalls Dan Wang and Arthur Kroeber's analysis on “The Real China Model”. They argue this model stems from what they call "deep infrastructure"—not just transport, but digital ecosystems and robust power grids. Plus 70 million skilled industrial workers. Entrepreneurial spirit comes last, built atop this foundation. Chinese AI companies are the visible iceberg tip; what enables their emergence lies "below the waterline."

H: This reminds me of a recent podcast episode between He Xiaopeng, founder of EV company XPENG, and Luo Yonghao (Luo is basically Joe Rogan of China in this context). He Xiaopeng shared an example: after learning that Elon Musk was building a factory in Mexico, he also went to Mexico to learn about building a factory there. The first problem he encountered was locals saying, "We don't have electricity here. You'll need to pay us some benefits before we can connect power for you." This is completely unimaginable in China.

Afra: Exactly. I read some reports show commercial electricity costs double China's, with three-year waits for new power allocations. This illustrates a crucial but overlooked concept: Infrastructure Friction Cost. Picture a high-performance car on potholed roads—constant braking, detours, component wear. That's friction cost. Electrical infrastructure gaps create massive friction. I actually learned this from

’s post that China has over 50,000 kilometers of ultra-high voltage lines moving energy nationwide. The US has almost none.

Afra: Let's discuss China's biggest misconceptions about America's AI landscape.

H: There are many. The Chinese AI community often displays overconfidence by misinterpreting struggles at Silicon Valley companies. For example, when Meta faces challenges with its Superintelligence efforts, many in China prematurely conclude that Meta’s AI is finished. However, Silicon Valley's greatest strength is its resilience, which creates a level of innovation uncertainty unmatched anywhere else in the world. You can't systematically defeat an entire industry—at most, one company might outperform another, but then new players rapidly emerge. This constant regenerative vitality remains unparalleled globally.

Afra: An AI founder friend in Beijing shared an observation with me: this constant disruption means major US companies never know when their position might be threatened. As a result, top executives maintain humility, personally engaging with emerging trends. When small startups build impressive products, industry leaders will directly message unknown founders: "Can I get an invite code?" Silicon Valley titans regularly reach out to small companies asking to try their products.

This reflects profound awareness in Silicon Valley—no matter how successful, you can't see everything or control all market information. Hence, greater humility. Chinese tech leaders lack this humble posture. In China, disruption alone isn't enough—you need government support, cutthroat competition, and overwhelming resource deployment.

H: Exactly. Despite decades of reform, China retains strong planning instincts. People believe you need systematic approaches, targeting industry leaders to achieve success. But Silicon Valley doesn't operate this way—that's the fundamental misunderstanding.

The second misconception relates to talent: Silicon Valley's top talent far exceeds what most Chinese observers imagine. When OpenAI or Meta encounter challenges, Chinese media often gloats prematurely. However, if you know people working there, you realize their talent pool is sometimes unparalleled in China. OpenAI's depth of expertise is truly remarkable. Even if I personally find GPTs somewhat underwhelming, no serious industry insider believes OpenAI has lost its edge. China's AI community sometimes exhibits excessive confidence, misreading achievements like DeepSeek's as conclusive triumphs. Yet substantial differences in product reliability persist between Chinese and US AI offerings.

Afra: Among top talent you've encountered, which types does China lack? I think figures like Demis Hassabis, who span philosophy, neuroscience, AI, game design, and entrepreneurship, are extraordinarily rare, and hard to systematically cultivate within any single country’s institutions, not to mention in China domestically. China's tech understanding is overly utilitarian. The prevailing mindset treats entrepreneurship as "making everyone rich," reflecting fundamental thinking limitations.

H: Right. We joke that someone of Jeffrey Hinton's caliber would be just a professor in China, couldn't advance further because existing evaluation standards wouldn't recognize his contributions.

Afra: Returning to the "Chinese AI" label, you said this is essentially geopolitical branding, right? Why?

H: Absolutely. China has numerous AI companies pursuing vastly different approaches. Look at Qwen, Kimi, GLM (Zhipu), including DeepSeek—each takes distinct paths. Only Baidu's Wenxin Yiyan isn't particularly open-source. The diversity is rich, but everything gets uniformly labeled "Chinese AI" despite different technical paths and cultures.

Afra: I've noticed this technical diversity. OpenAI and Anthropic (Claude) occupy similar categories, competing for similar users. But Chinese models all seem to pursue different routes. Why so little overlap?

H: Probably because China occupies a catch-up position. These technologies originated in North America, so China's investment environment lacks convergence effects. Foreign investors roughly understand what to fund because OpenAI established benchmarks. As followers, Chinese investors have no unified standards—everyone knows OpenAI's level seems unreachable. So they try various angles, seeking second-best approaches. When DeepSeek suddenly broke through early this year, people thought they'd found direction. Later they realized it was a unique, non-replicable case.

Afra: Exactly. I discussed with an AI professor in Shanghai why DeepSeek isn't typical under Chinese standards—not a planned economy product, but an unreplicable path. It's an outlier. We shouldn't analyze DeepSeek through Chinese system frameworks. A quantitative trading firm suddenly hoarded massive GPU resources, deciding, "let's build something." In extremely resource-scarce conditions, with determination to squeeze every computational cycle, they achieved success through pure resource overwhelming—"大力出奇迹 (massive effort creates miracle)” in its purest form.

Afra: Let's shift to the next topic. How do AI ecosystem topologies differ between China and the US? I would love to talk about funding flows, government roles, cultural factors, talent supply.

H: "Topology" is perfectly apt. The US excels at industrial collaboration—clearly superior to China. Take Hugging Face, beloved in open-source circles. From compute access to ecosystem building, application deployment to investment, the entire chain is highly mature.

China's situation differs fundamentally. You might have brilliant ideas, but resource acquisition channels aren't as smooth. Consequently, we've developed what I call circle-based interaction models. Let me walk you through the seven key circles I've identified:

Academic circles—like CCF (China Computer Federation), a massive organization. Plus numerous national labs. Within this circle, you can access resources including compute and talent pools—many students who can become developers.

Big tech ecosystems—Alibaba's Qwen, Tencent's Hunyuan, Doubao. Each major tech enterprise maintains its own ecosystem.

Industry institutions—many government-led or supported, like CAICT (China Academy of Information and Communications Technology), a leading scientific research institute and think tank. They organize cooperation, set standards, and conduct certifications.

Large research institutions—Beijing’s Zhiyuan Institute (Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence, or BAAI), which contributes heavily to Hugging Face. Shenzhen’s Peng Cheng Lab, Shanghai Innovation Institute. These accept government missions but rely primarily on enterprise and university support.

Pure open-source organizations—China has OpenAtom Foundation. Plus overseas or global scientific foundations active in China and Asia-Pacific. Not branch offices, but they organize activities that China recognizes. Linux Foundation is the largest.

Startups and their investment circles—investors in Zhipu, Moonshot, ModelBest form their own circles. Each investor has their network, though circles collaborate.

DeepSeek's circle—unconventional, existing in completely unique ways.

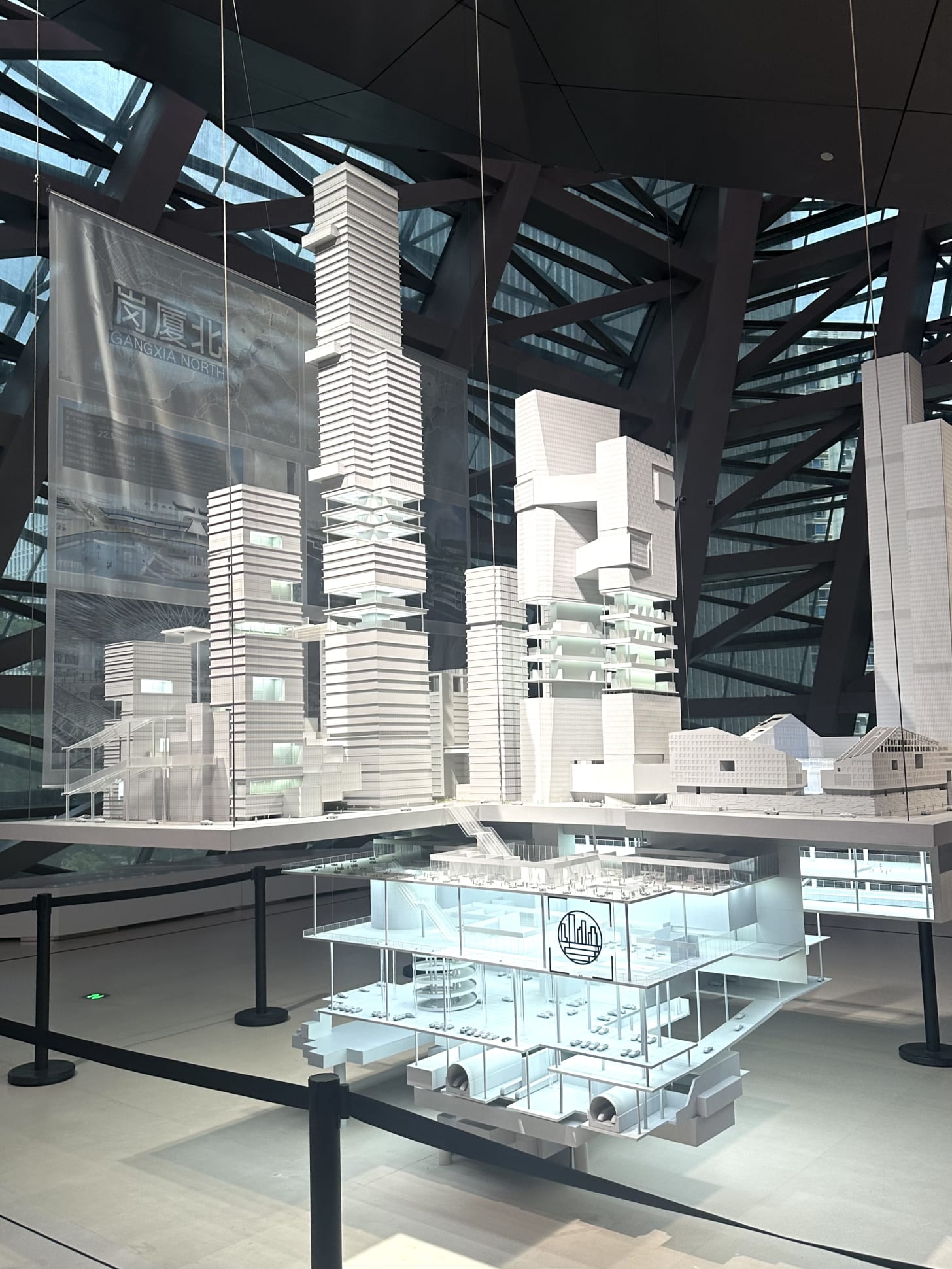

Afra: Regarding large research institutions, this circle structure differs vastly from the US. I recently visited Shanghai Innovation Insitute and was stunned by the scale of “AI Town" where it's located (I'll write about this experience later). I realized this Shanghai government-backed institution connects top universities, leading research bodies, major enterprises, unicorns, and startups. It's only one year old but already contributes significantly to the industry, right?

H: Absolutely. They recently held a launch event we all attended. Lu Qi invited his circle to participate, though he preferred staying behind the scenes. That's their unique ecosystem—we frequently collaborate with them.

Overall, China's AI topology is layered circles communicating through intersection points. These circles aren't mutually exclusive—they communicate through shared personnel. I believe that's the model.

Afra: From this topological perspective, how else do Chinese and American AI circles differ culturally? What about founder archetypes?

H: Archetype differences aren't actually that significant. The domestic situation resembles multiple overlapping circles seeking intersections—not two-dimensional, but three-dimensional. Imagine multiple spheres finding intersection points.

North America's advantage is industrial integration speed. Though purely market-driven, it achieves market leadership and profitability extremely fast. America has champions at every level—NVIDIA dominates hardware. Each AI industry layer has a champion providing ecosystem leadership and support.

I need to better articulate America's model—it's like converging arrows rapidly generating combined force. Leading enterprises create momentum, quickly forming layered industrial cooperation. The advantage is speed; the disadvantage is insufficient market diversity.

China is exactly opposite—the circle structure I described has numerous spheres, ensuring adequate diversity. But coordinated action is weaker. This is why government plays crucial roles domestically. Government policies emerge from stakeholder negotiations—you need authority to provide compromise directions. This way, sphere intersections can converge like North American arrows, though still slower.

Afra: Why do you think North American arrows converge so rapidly, forming such a combined force?

H: Partly because America's industrial history is mature—habits are established. "Open source," for instance, requires education in China but exists like air, water, sunlight in America. Even new Google engineers understand these concepts naturally.

Afra: So even the most highly educated Chinese graduates from top universities like Tsinghua and Zhejiang University still need to be educated about open-source concepts? There's a learning curve?

H: Exactly. Open source is just one example. This explains why American leading enterprises rapidly form what I call "arrow convergence"—consensus emerges quickly. Jensen Huang doesn't need day-long meetings to identify partners. He instinctively knows: "If I develop this type of hardware, I need these specific software partners." He understands what to open up for broader cooperation. Because America's industrial foundation runs so deep, much of this collaboration emerges naturally.

China, however, has only been developing for forty years. People have just recently moved beyond subsistence concerns, making it easier to form circle-based interest communities initially. Coordinated action remains challenging because many have only recently secured their basic needs. The prevailing mindset is "secure my plot first"—"let me eat first." With most people maintaining this perspective, government action frameworks become necessary: "Comrades, stop competing individually. Let's align on this direction for the next year and focus our investments here."

Afra: This consensus—whether bottom-up or top-down—requires long-term innovation and openness to mature, as well as a fairly wealthy society like the US.

H: Including mature capital markets. In America, everyone understands investor expectations—Series A, B, C rounds have established benchmarks because the system has evolved over decades. This is why emerging industries predominantly incubate in Silicon Valley—the ecosystem knows its role, and execution is efficient.

Afra: Tell me about founder archetypes between China and America. I have a lot of thoughts on this, but I would love to hear your opinion.

H: Chinese and American founders are very similar—both are businesspeople optimizing for market opportunities. Chinese VCs learned from Western models, so our entrepreneurs follow the same playbook.

What's new is a small cohort emerging around figures like Liang Wenfeng from DeepSeek and Wang Xingxing from Unitree. These younger founders are mission-driven rather than opportunity-driven. They have uncompromising technical visions—more like Google's "organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful" idealism than typical Chinese pragmatism.

Afra: He Xiaopeng strikes me as this type—discussing flying cars in that podcast with such conviction, predicting 2026 deployment. He combines Musk-like moonshot visions with surprisingly grounded execution. I also found Wang Xingxing inspiring. I remember how he talks about terraforming the Earth with robots with such burning idealism.

H: In fact, He Xiaopeng represents the older generation—they are good at what I call "internet officialese." He's still fundamentally an opportunist who pivoted from internet to EV. The new breed is different: they're domain experts pursuing technical missions, not internet veterans seeking new markets. Consider the contrast: NIO, Xpeng, and Li Auto were all founded by internet entrepreneurs who saw EV as the next big thing. None started with deep automotive insights or technical missions. They're sophisticated in presentation but provincial in thinking. Ironically, Huawei inverts this—provincial and intensively “Chinese” in presentation but genuinely Westernized in technical culture and methodology.

The next wave of leading founders will be true automotive engineers and energy specialists building companies around technical breakthroughs rather than market opportunities. Like that flying car founder (Zhao Deli) XPENG invested in—he's crashed testing his own prototypes three times. That's mission-driven founders: they'll risk everything for the technology itself.

Afra: The phrase that came to mind when I heard this story was "Chinese dynamism."

Your observation about Huawei being "sophisticated and international beneath, provincial and Chinese on surface" highlights a broader issue: Chinese entrepreneurs' reluctance to become sources of knowledge production. Silicon Valley abounds with philosopher kings writing books and outputting ideas. Chinese entrepreneurs largely choose silence or rely on ghostwriters. This creates external misunderstandings—America remains the knowledge exporter while China over-imports and under-exports.

H: I'm an All-In Podcast devotee. Discussing those hosts with my wife, I realized: Chinese founders lack the ability to discuss topics formally in informal settings. They polarize—either bluntly casual in private or rigidly scripted in formal.

Afra: How do you view "guanxi (meaning relationship)" in China's AI ecosystem?

H: Regarding guanxi—unavoidable wherever people gather, especially in China’s cultural environment. Their core function is resource allocation. Computing power, funding, project access—whether you get projects, participate in core processes—all are influenced by guanxi. Though I mainly meant "official relationships," private "circle culture" matters equally.

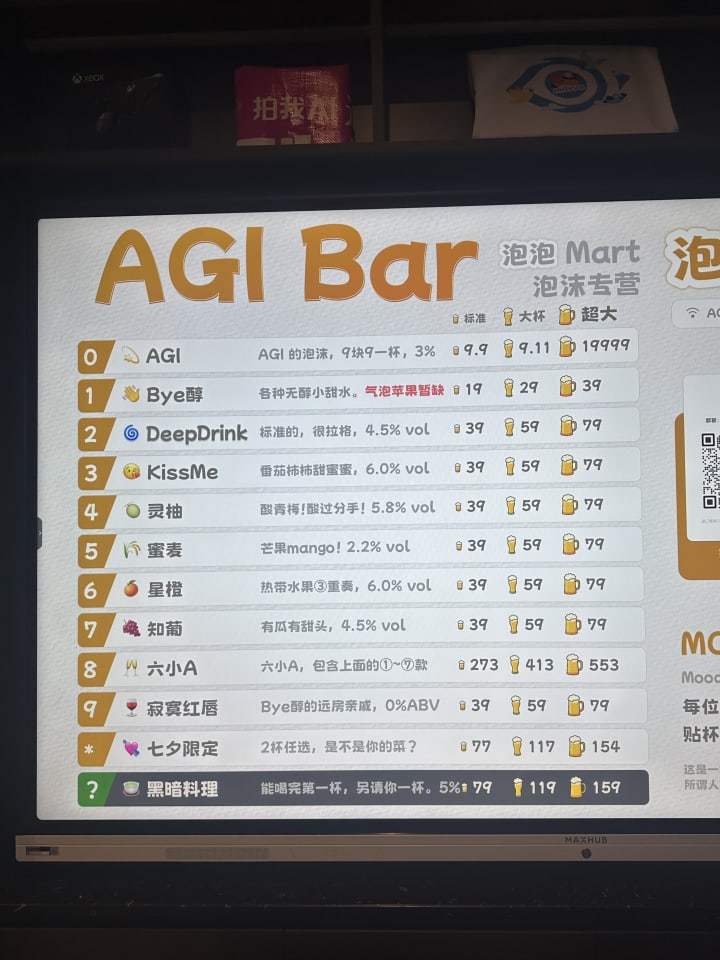

Afra: Speaking of circles and guanxi, a recent Beijing experience is worth elaboration. Researching Beijing's AI ecosystem, I asked my Shanghai and Shenzhen tech friends "where to find Beijing's AI scene?" All recommended "the newly opened AGI Bar on Zhongguancun Startup Street." I investigated—this café is run by Chinese AI KOL "Big Smart 大聪明," who runs a WeChat official account similar to a Substack newsletter called "Cyber Zen Heart 赛博禅心." So I visited AGI Bar, catching the 8-9 PM free drinks period and meeting the owner (who's there almost daily).

Chatting, I immediately sensed that distinctly Chinese “circle” flavor, especially the information brokering mystique that exist in Northern China: he claimed, "I understand Chinese AI companies' underwater operational patterns." I couldn't verify his claims, but witnessed his influence. My friend and I dubbed him "China's Lenny." Given market opacity plus Beijing-Tianjin's unique "small circle culture," that unfathomable feeling was intense. Shanghai and Shenzhen lack this obviousness—Beijing seems particularly rife with such "mystique peddlers." Oh, and he is a meme lord. Every corner of the AGI Bar is filled with memes and puns that are pretty mid.

H: Right, Beijing has many such information brokers.

Afra: Upon reflection, I questioned: despite his big social media following and influence in consumer AI circles, how much actual intersection does he have with truly productive companies like Zhipu? To what extent does he actually help these enterprises? What's the real overlap between his claimed "asymmetric information" and publicly available market data? None of this is verifiable. He creates an illusion of transparency by seemingly answering every question while remaining fundamentally elusive. In the US, by contrast, even claims about "strong investment connections" require specificity—"I have concrete relationships with Sequoia or a16z"—with transparent foundations.

H: What you encountered is a very distinctly Chinese characteristic.

Afra: My friend and I were trying to process what we saw at AGI bar, unsure whether this was a broadly Chinese or specifically Beijing phenomenon. We had previously discussed US-China funding structure differences—America's A, B, C round delineations are clear and standardized, while Beijing's AI field, with its high technical barrier and high industry stakes, has transformed native AI circles into something that feels as murky as state-owned enterprises.

Afra: Let's examine the policy dynamics. After DeepSeek emerged and crashed the US stock market, the top leaders in China seemed to "rediscover AI" as a strategic priority while America launched unilateral AI geopolitical rivary. But I suspect this narrative of sudden policy pivot misreads how Chinese industrial policy actually operates. How do you view this moment of apparent "strong intervention"?

H: Two key points. First, Chinese AI industrial policy breadth was established early—not a DeepSeek reaction. China’s political system differs from the West, but information flows effectively. Otherwise we'd be a "failed state" as Acemoglu and Robinson describe in Why Nations Fail.

Afra: How does this policy machinery actually function?

H: The state maintains specialized "jurisdictional departments 归口部门" dividing society into sectors, with heads regularly soliciting stakeholder opinions. Beyond the "Two Sessions" parliamentary cycle, various ministries and commissions routinely collect industry feedback. AI policies were already advancing, and integrated circuits as industrial priorities predated AI fever.

Afra: So there's this continuous feedback loop between industry and government that most Western observers miss. But what fundamentally changed with DeepSeek's emergence?

H: Industry confidence, I would say. Before this breakthrough, from top leadership down to practitioners, everyone believed China's software foundation was hopelessly backward. I've spoken with several top-tier industry professors—before DeepSeek burst onto the scene, their feedback was uniformly "despairing." They felt the software and engineering capability gap couldn't be bridged in just a year or two. Hardware gaps are also substantial, but hardware represents "industrial system behavior"—it doesn't require extensive "cultivation of human spirit." (Here it refers to developing the intangible qualities that make someone truly excellent - not just technical skills, but wisdom, creativity, judgment, and innovative capacity. It's what distinguishes a master craftsman from a factory worker, or a visionary engineer from someone following instructions.) As Geng Yanbo explained in The Chinese Mayor documentary we both like, CCP’s operational philosophy is: "Once core objectives are clarified, all cadres and resources mass around that target until mission accomplished." DeepSeek's impact was proving China could excel at LLM-level innovation, not just hardware.

And it provides benchmarks. Now with domestic standards like Qwen, Zhipu, and Pangu, government can collaborate with these companies to clarify standards, enabling precise policy implementation—tax incentives for "hardware-optimized software" startups. This "software-side policy intensification" represents DeepSeek's not-yet-fully-apparent transformation.

Afra: I've learned from a previous conversation that I wrote about that top AI companies like DeepSeek seem directly overseen by ministries and commissions—either reluctant to issue statements or maintaining direct State Council communication channels. This reflects a more sophisticated state-enterprise relationship than Western perceptions suggest.

I've learned from previous conversations that top AI companies like DeepSeek seem directly overseen by ministries and commissions—either reluctant to issue statements or maintaining direct State Council communication channels. But this reflects something more sophisticated than crude state control. What's particularly Chinese is how this operates through fierce inter-provincial competition that emerged after economic reforms—provinces now compete for talent, investment, and prestige like corporate rivals. In China's system, companies essentially become "assets" of their host cities, with local governments taking pride in and responsibility for locally-based success stories. This suggests a more nuanced state-enterprise relationship than Western perceptions typically acknowledge

H: If true, it's actually normal—involving two objectively existing aspects.

First is about "external communication management": this relates minimally to central authority, more to "post-Reform regional competition dynamics." For instance, DeepSeek's external communications require approval from Hangzhou Municipal Party Committee propaganda departments—because its headquarters is in Hangzhou.

Example: Wang Xingxing and Liang Wenfeng are both Guangdong natives. This Spring Festival, the Guangdong government dispatched representatives to visit Liang Wenfeng's hometown, with the subtext: "You're Guangdong-born—why establish enterprises in Hangzhou instead of benefiting your homeland Guangdong?" Later, Guangdong Provincial Party Committee specially convened meetings discussing "why Guangdong missed Liang Wenfeng." This provincial-level regional competition is commonplace domestically—external communication management essentially represents "local resource binding to locally-based enterprises."

Second is "ministry and commission communications": any industry-leading enterprise maintains direct communication channels with State Council ministries 部委 and commissions—quite normal, but not the Western-imagined "state apparatus directly intervening in enterprises." Forty years of Reform and Opening have matured technocratic bureaucrats who understand the principle that "grip too tight and you kill it.

Afra: This provincial competition fascinates me because it shows how governments actively court and sometimes guilt-trip successful entrepreneurs, treating talent retention as a zero-sum competition between regions. I read one commentary (in Chinese) anxiously reflecting on why Guangdong Province missed DeepSeek. Part of this article is about Guangdong's identity crisis over losing talent retention and its innovative aura.

This also reminds me of conversations with a political scientist Bao Gangsheng, during his visit to Stanford—he said Chinese bureaucratic governance logic involves two elements: development and control. Forty years of reform refined their "measure calibration" to perhaps greater sophistication than imagined. Especially in technology and economics, this calibration has formed mature practices—they won't commit acts like "slaughtering pigs before fattening,” because they've learned that the government’s premature intervention destroys the very tech capabilities the government seeks to harness.

Afra: Let’s talk about hype: which Silicon Valley trends do you find most over-hyped? And which China’s AI directions or products do you think are underrated?

H: Regarding Silicon Valley, the previous MCP (Model Context Protocol) hype genuinely irritated me. From those of us actually building technology, it's just routine optimization—yet VCs inflated it into the next "gold rush." Classic bubble behavior. AI Agents are similarly overheated right now.

Meanwhile, truly fundamental work like "efficient cluster management" gets completely overlooked. North America has brilliant ex-Intel engineers, Google's R&D ranks among the world's absolute best, but "cluster management" is too unsexy for anyone to treat as ecosystem-defining. This creates a dangerous blind spot: when the inevitable downturn hits, all that specialized talent will evaporate.

China presents the inverse scenario: while AI had its hype cycles, today's "semiconductor sector over-speculation" is far more problematic. Some chip company valuations are genuinely absurd. This stems from our industrial policy architecture—the state still favors hardware support, so everyone calculates that "riding the chip wave offers higher certainty than software startups." You can tap policy subsidies with lower risk than pure software plays.

Conversely, directions like "software-hardware co-optimization"—though DeepSeek provided some momentum—remain severely undervalued due to prohibitive technical barriers and insufficient "sexiness." Yet for Chinese AI startups, this capability represents authentic competitive differentiation. Software innovation is systematically underestimated.

Afra: Let's return to the moat question—how deep and wide are Chinese AI companies' moats?

H: At the foundational model level, we lean toward Google's earlier assessment: "We have no moat." Even trailing 18 months behind doesn't necessarily mean you can't catch up. But Chinese AI possesses a structural advantage that mirrors the new energy vehicle playbook.

America's strength lies in sophisticated capital markets that rapidly funnel emerging industry resources toward a single "category king"—Tesla in electric vehicles being the textbook example. But the weakness is glaring: there are too few kings. Tesla has been developing for nearly two decades, yet the US still lacks a stable number-two player. From our perspective, this is bewildering.

Put simply, the US operates on oligarchic dominance—one clear leader with virtually no second tier. China runs on wolf pack hunting. In EVs, it's not just BYD challenging Tesla solo—you have the "NIO-XPENG-Li Auto" triumvirate plus dozens of others forming a genuine ecosystem. AI follows the same pattern: while DeepSeek emerged as the flagship, China harbors numerous promising contenders. The US? You can count on one hand: Google, OpenAI, Anthropic—the "holy trinity," and that's it.

This structural difference creates inevitable consequences: the US excels at establishing early dominance, but once the race enters marathon territory, innovation stagnation becomes almost inevitable. Three companies, talent circulating within the same Silicon Valley bubble, HR departments practically operating as cartels—convergent thinking becomes unavoidable.

China gets criticized for "involution," but destructive involution means redundant low-level competition. Productive competition has immense value—it forces everyone to answer "why should customers choose me?" and "why should developers partner with me?" Pure differentiation pressure. When facing a "wolf pack" competitive environment, the entire industry's innovation timeline gets extended. Given sufficient runway, this pack-hunting dynamic creates emergent moats. If Chinese AI companies grind out novel architectural breakthroughs, or even application scenarios that simply don't exist in North America, then the Valley genuinely can't respond—they lack the corresponding use cases to even begin developing adaptive technologies.

Afra: Chatting with friends recently, I had a similar intuition—perhaps future breakthrough AI applications will have the US "crossing the river by feeling China's stones."

Afra: When we met before, you mentioned your daily routine as an open-source AI engineer in China—waking up to doomscroll X, check post on LessWrong. Who’s your favorite shitposter in AI circles?

H: Probably Teortaxes (pseudonym), I quite like him. Though I've never met him, his persona is interesting: clearly disapproves of Putin but deeply loves Russia, typical Russian "exile intellectual," now living in Argentina—choosing an environment completely different from Russia, yet deeply proud of Russian culture. Precisely because of his background, he's interested in Eastern culture and Chinese tech dynamics, very open-minded with relatively objective viewpoints.

Afra: I just followed him. He has a strange presence—he posts Chinese-language content, no idea who taught him.

H: Teortaxes and I actually connected before the DeepSeek moment. Late 2022 through late 2023 was a fascinating period—ChatGPT had just dropped, everyone was still figuring things out, open-source models were scarce. As practitioners, we hadn't yet developed today's "AI doom anxiety" but were genuinely electrified by the technology—it felt like witnessing a genuine technological inflection point.

My immediate reaction was deleting Zhihu entirely. Chinese social media felt like nothing but recycled content and secondhand takes, no original signal. I ended up spending countless hours on LessWrong instead. That's where TXT and I first crossed paths, during those intense discussions about "what does the Transformer architecture actually represent?" When Sora launched, the technical discourse there was incredibly rich.

As I mentioned when you visited Shenzhen: China's AI scene is hypercompetitive and innovative, but suffers from metaphysical poverty—everyone's heads-down executing, rarely pausing to ask "what is the fundamental nature of this technology?" Silicon Valley has the opposite problem: too many philosopher kings.

DeepSeek's eventual rise partly traces back to Teortaxes’s conviction from their very first paper that "this approach is fundamentally different." I shared that intuition, but when I'd mention it to others, the universal response was DeepSeek was "just another scam"—this was November 2023. His unwavering DeepSeek advocacy eventually made him famous, becoming AI circles' leading DeepSeek evangelist.

Two things draw me to him: First, his sardonic wit hits me hard—that particular brand of razor-sharp irony and twisted logic only emerges from environments with constrained speech: China and Russia. Most Western commenters completely miss the subtext and just rage in the replies, but those of us from a speech environment immediately get the jokes. Second, his perspectives are genuinely balanced—he catches heat from both Chinese nationalists and Western hawks, which typically indicates someone speaking uncomfortable truths. I'd love to meet him in person someday—either he visits China or I make it to Argentina.

Afra: You've mentioned sourcing your AI news from X and LessWrong—so what, in your view, is Zhihu's role within China? Personally, I feel that most of the rumors and bad tech memes in China's AI world start on Zhihu. It's also notorious for the sheer volume of bad takes from Chinese STEM types; they'll debate technology, geopolitics, history, and everything else on Zhihu, but the conversations usually stay shallow and dressed up in rationalist and progress-driven language.

There's also the "industrial party" cult on Zhihu. I am talking about the people who fetishize China's manufacturing capacity and technological self-sufficiency as the ONLY solutions to complex problems such as geopolitical tensions and, let's say, gender wars. In a sense, Zhihu is more like China’s 4chan. Zhihu also designed for individual expertise performance rather than truth-seeking. The platform rewards confident pronouncements: if you are a 20-something male who graduated from Tsinghua University, congrats, you are the chosen Zhihu golden child and you will gain a lot of traffic and applause. I want to hear your take. Do you see Zhihu as China's equivalent of LessWrong?

H: Absolutely, but it's more complicated than a direct parallel. China currently has no viable X substitute—Weibo collapsed long ago, WeChat completely lacks public discourse functionality, leaving Zhihu as the sole remaining venue for technical discussion. But its social dynamics never properly developed, making it essentially a least-worst option.

For AI discussions, X’s core value lies in enforcing accountability—even authority figures must answer for their statements. China's AI luminaries and industry titans exist within insulated comfort bubbles—major corporations won't challenge them, local governments treat them like dignitaries, academicians hold actual administrative ranks equivalent to ministerial positions, so public criticism becomes unthinkable. But on X, regardless of your status, if you dare open-source or voice opinions, someone will push back hard, even directly contradict you. This environment proves invaluable: it attracts people genuinely committed to technical discourse. This explains why Chinese AI teams announcing breakthroughs still gravitate toward X for publication—they receive authentic feedback.

China lacks such accountability mechanisms. Though Zhihu enables technical discussion, its weak social architecture prevents sustained intellectual exchange from taking root.

Afra: Another observation: in China, few people seem to genuinely believe in AGI - what I mean by AGI is Superintelligence. When Chinese founders or tech leaders talk about AGI, it's likely because the term delivers tangible benefits—prestige signaling, government subsidies—rather than authentic conviction that "superintelligence is coming." This reveals a deeper epistemological divide. Silicon Valley's AGI discourse operates like what Kevin Kelly calls "technium" thinking—technology as an autonomous force with its own evolutionary trajectory. Chinese tech culture, by contrast, remains fundamentally instrumentalist. Do your observations align?

H: Completely. China's philosophical establishment fundamentally doesn't cultivate this kind of "technological faith." The overall intellectual climate misaligns with AGI's required "rational technical messianism." Within the industry, I can identify perhaps only DeepSeek's Liang Wenfeng as someone genuinely committed to AGI. But his belief isn't empty rhetoric—it's anchored in concrete technical convictions. He's absolutely certain that "AGI's essence must be sparse architecture." Every DeepSeek decision, from model design to optimization priorities, radiates from this core vision. Such philosophical coherence is vanishingly rare among Chinese entrepreneurs.

Afra: How should we understand "sparse architecture"?

H: It derives from human brain characteristics. Consider: human cognition operates "sparsely"—incredibly low bioelectrical consumption yet achieving efficient learning and reasoning, making it nature's most "performance-optimized" computing system. We can't instantly memorize entire books like LLMs, but human knowledge transfer capabilities are extraordinary: learning one domain's principles and applying them elsewhere, even reverse-engineering the machines that might achieve AGI.

Liang Wenfeng believes AGI reaching human-level efficiency must possess this "sparsity." Hence DeepSeek's relentless focus on Mixture of Experts (MoE) and low-bit quantization—all fundamentally pursuing "sparse computation." Mixture of Experts originated at DeepMind, but high implementation complexity and deployment costs prevented adoption until DeepSeek scaled it successfully.

Afra: Right. Silicon Valley has essentially transformed "believing in AGI" into tribal membership. Zuckerberg recruiting emphasizes AGI vision; leading voices like Demis Hassabis and Eliezer Yudkowsky treat AGI with religious fervor. Where Silicon Valley valorizes technological transcendence, China maintains what I'd call pragmatic materialism—the persistent question isn't "will this achieve superintelligence?" but "can it ship, can it generate revenue, can it serve strategic objectives?" I was in Shanghai’s Mosu Space (a government-led AI accelerator) and saw a bunch of human-sized signs displayed in a big public square, each sign says an AI buzzword. “AGI” is among them - but it reads very differently.

.png)