Sunken finds in the South China Sea testify to rich trade networks used over hundreds of years. The sea routes brought porcelain, tea and other goods from Asia to Africa, the Middle East and Europe

Sean Kingsley - History Correspondent

October 22, 2025

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/92/ae928a2b-0186-4503-be7f-bee8f4a26e66/lede.jpg) Divers excavating the 12th-century Huaguangjiao One wreck uncover stacked Song dynasty bowls.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Divers excavating the 12th-century Huaguangjiao One wreck uncover stacked Song dynasty bowls.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

On a spring day in 1848, the first Chinese junk to sail Atlantic waters arrived at the East India Docks in London. To Charles Dickens, the roughly 800-ton Keying looked nothing like a long-distance trader, instead resembling a “floating toy shop” and a grotesque “torture of perplexity.” China had no idea how to sail the seven seas, the British author argued, in typically imperialist fashion.

Western thinking has for centuries clung to the belief that China’s rulers distrusted sea trade. After all, the Great Wall of China, swerving between valley, mountain and sky for some 13,000 miles, was built to keep invaders out and landlock China’s citizens in the bosom of the empire.

In the 21st century, however, China is positioning itself as a civilization steeped in maritime history that equals or surpasses colonial Europe. At a 2017 forum to promote China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, President Xi Jinping said, “Our ancestors, navigating rough seas, created sea routes linking the East with the West, namely, the Maritime Silk Road. These ancient silk routes opened windows of friendly engagement among nations, adding a splendid chapter to the history of human progress.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/10/091081b5-7dbe-4a23-9aa5-fde5f9662569/keying.jpg) The Keying, the first Chinese junk to sail British waters

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Keying, the first Chinese junk to sail British waters

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

China’s seafaring ways took off under the Tang dynasty (618-907 C.E.), when Persian merchants in the vein of the mythical Sinbad the Sailor shouldered the risks of life on the water. For the next millennnium, until the Opium Wars shattered peaceful trade relations in the mid-19th century, a Maritime Silk Road ran from northeast China to the Red Sea. Silk was just the tip of the iceberg: Cargo ships were crucial for transporting bulk goods, including porcelain, chests of tea, spices and medicines. Until recently, evidence of this sunken past was largely hidden from sight. Today, however, an array of Chinese coastal cities, from Quanzhou to Hepu, compete to be recognized as the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road.

To some observers, the Maritime Silk Road is more of a modern political invention than a historic version of the land-based Silk Road, which ran from northwest China all the way to the Mediterranean coast of southeast Turkey. But stunning new shipwreck discoveries deep under China’s seas support this grand naval narrative, shedding sensational light on a mighty ocean road to rival the Great Wall.

A pair of stunning Ming dynasty shipwrecks

The China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea, which opened on Hainan Island in 2018, is a cultural gem that shines a spotlight on this rich history. The museum displays artifacts from more than 15 shipwrecks found across China. Under the Western Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-25 C.E.), the kingdom’s southern shores became a “golden waterway” for ships sailing the Maritime Silk Road, one of the museum’s exhibitions explains. During the Song dynasty (960-1279 C.E.), trade peaked, and ships sank in ever-greater numbers. The museum’s displays trace this history and beyond, covering the period between the 10th and 19th centuries.

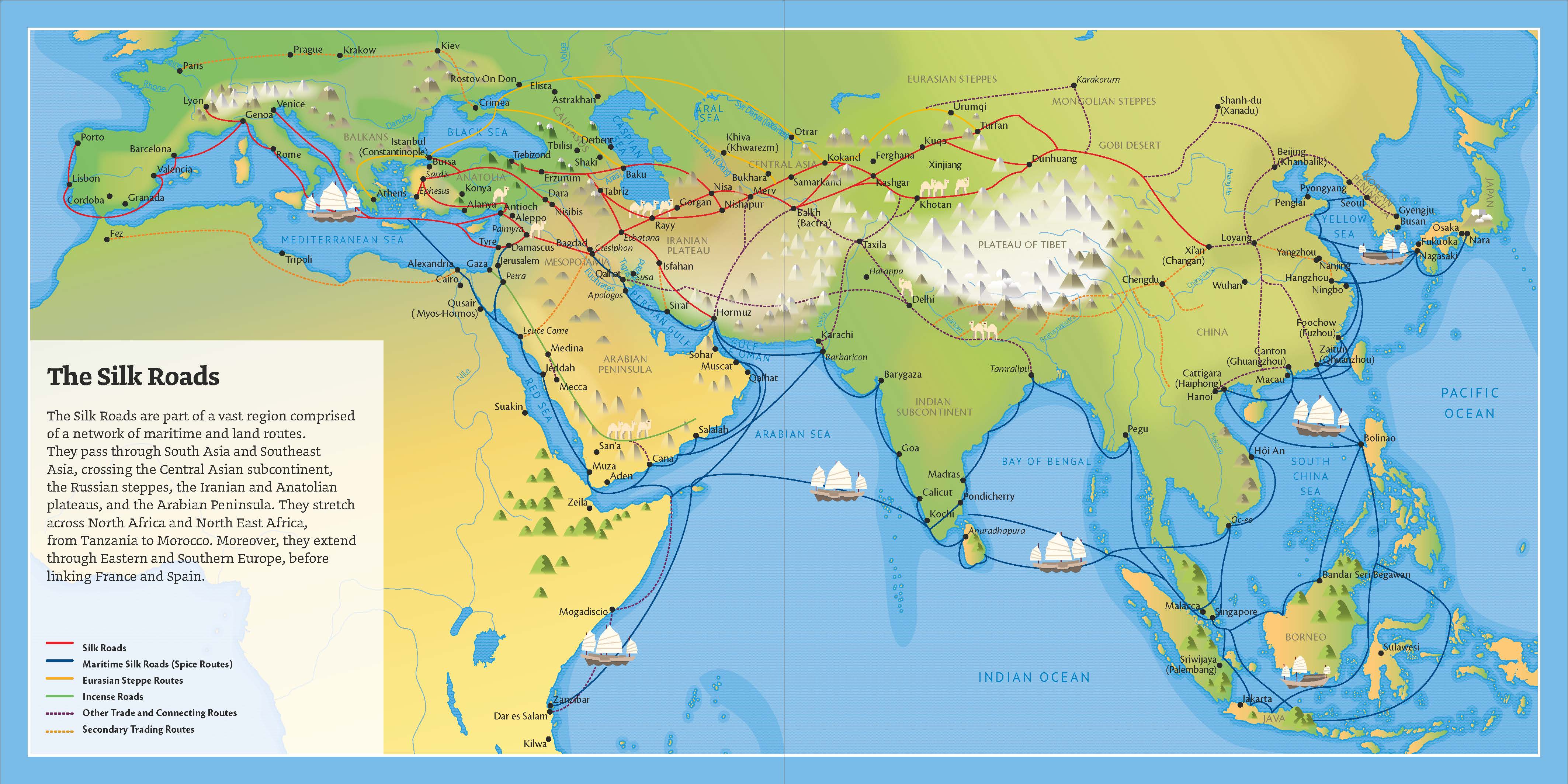

A map of the various Silk Roads, with the Maritime Silk Road marked in black / Courtesy of Unesco

A map of the various Silk Roads, with the Maritime Silk Road marked in black / Courtesy of Unesco

Inside the museum, masses of porcelain and pottery are rewriting the art history and dates of ceramic styles crafted in China’s legendary kilns. Also on view are life-size stone statues from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), representing the Daoist deities Fu, Lu and Shou (Fortune, Prosperity and Longevity). The sculptures were commissioned for ancestral halls and temples but ended up wrecked off Coral Island while heading to Chinese expatriate communities in Southeast Asia.

Other displays showcase encrusted treasures, including Ming dynasty (1368-1644) copper coins and Edo era (1603-1868) Japanese gold coins. A couple of rusted iron cannons lost during naval patrols in the South China Sea in the early 18th century stand nearby.

But it is the fruit of China’s most recent maritime exploration that takes pride of place in the museum. Around 93 miles southeast of the city of Sanya on Hainan Island, two mid-Ming dynasty shipwrecks, untouched by fishing trawlers or trophy-hunting divers, lie at a depth of about 4,920 feet. Discovered in 2022, the wrecks are a major breakthrough in deep-sea underwater archaeology by China, which is investing $4.7 million annually in their study. The vessels are also game changers in understanding how goods flowed in and out of China—how East met West.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/9d/609df9c3-c7b3-4a21-bf58-425983ae4ba0/2hainan.jpg) Copper, silver and gold coins recovered from shipwrecks in China for display at the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Sean Kingsley

Copper, silver and gold coins recovered from shipwrecks in China for display at the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Sean Kingsley

One ship, sunk during the reign of the Zhengde emperor (1505-1521), holds a multicolored mound of some 100,000 pieces of porcelain and metalware. The second ship, wrecked with a cargo of wooden logs when the Hongzhi emperor was on the throne between 1487 and 1505, looks less spectacular but has a unique backstory.

The site mapping, cargo recovery and forthcoming excavation are the product of a collaboration between the museum, China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration, and the Institute of Deep-Sea Science and Engineering at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

As a museum exhibition explains, the “perpetually dark environment is characterized by low water temperature, immense hydrostatic pressure and extremely limited visibility.” It’s far too deep for human divers, so China deployed the Deep Sea Warrior, a 20-ton, 30-foot-long bathyscaphe submersible that took eight years to build and can spend up to ten hours underwater with a three-person crew. The submersible has recorded the Ming wrecks using high-resolution sonar and a tool that allows scientists to peer beneath the surface mud.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/87/cf879362-129f-43ff-9b3e-89890e1808bf/3hainan.jpg) The Deep Sea Warrior submersible

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The Deep Sea Warrior submersible

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

So far, archaeologists have recovered 961 finds from the Zhengde trader, building a staggering collection of blue-and-white bowls, glazed vases, green celadon, iron-red porcelain and three-color sancai wares, says Zheng Ruiyu, head of the exhibition department at the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea.

The wreck is colossal, with a height difference of ten feet between jars stacked in the upper hold and bowls crated near the keel. Between these storage spaces lies a vast void created by the decay and collapse of wooden bulkhead compartments and the decomposed organic or liquid cargo once stored there.

These goods might have been headed from China’s Guangdong Province to markets in Southeast Asia and buyers in the Muslim countries of West Asia, who commissioned custom-made plates for communal dining. The junk’s merchants catered to everyone from street vendors to high-ranking officials and nobles, “a multilayered market structure … demonstrating a sophisticated overseas trade strategy aimed at satisfying the needs of a broad range of social classes,” says Zheng.

Ceramic dishes found in the wreckage of the Zhengde trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Ceramic dishes found in the wreckage of the Zhengde trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Blue-and-white bowls, coarsely painted with motifs such as double lions playing with a pearl, found buyers in middle-class markets. A large blue-and-white jar decorated with a scene of the mythological Eight Immortals, meanwhile, was a top-tier good “whose craftsmanship and decorative quality are in no way inferior to the treasured heirlooms in the Palace Museum,” a sprawling complex in Beijing’s Forbidden City, Zheng says. The wreck’s exquisitely designed fahua vases are also “unprecedented” in quantity and quality, he adds. The slip-trailing of piped lines of clay onto one of the vase’s surfaces created a distinct three-dimensional effect, showcasing peacocks and peonies amid a sea of clouds.

A humble 38 finds have surfaced so far from the Hongzhi trader, which was mainly transporting at least 660 wooden logs. Still, the wreck fills a gap in knowledge about return voyages sailing the Maritime Silk Road back to China. “The presence of two ships, one outbound and one inbound in close proximity, proves they were following a mature and busy ancient maritime route,” says Zheng.

Derek Heng, a historian at Northern Arizona University who was not involved in the research project, says that the ship’s cargo of raw materials is a missing scientific link. While ceramic, which is resistant to degradation underwater, holds “an iconic importance in global art history,” he explains, “the most valuable trade between East and West, other than gold and silver, was in natural products, including foods, spices and medicines that tend to decompose quickly in marine environments.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/e0/8fe01993-cfb2-4c58-a55c-e3a3305819dd/6hainan.jpg) Timber logs from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Timber logs from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The roughly ten tons of logs, the longest of which measure more than eight feet, are ebony wood stacked in two parallel lines along the ship’s width. Ebony, or “blackwood,” as it was known at the time, is native to tropical Asia and Africa and “was highly prized for its jet-black color and smooth surface when polished,” says Heng. During the middle years of the Ming dynasty, he adds, Chinese furniture-making created demand for ebony, which was “all the rage among China’s literati class.” Examples included writing and painting tables used in scholars’ studios and high-ranking officials’ armchairs.

China’s love of ebony wood furniture took off during the reign of the Jiajing emperor (1521-1567). The deep-sea ship lost in the South China Sea likely sank before the end of the Hongzhi emperor’s reign in 1505, making it a trailblazer predating the golden age of Chinese furniture.

Deer antlers and Turbo marmoratus shells found on the Hongzhi trader are even more curious survivors of Ming-era Asiatic trade. Deer were venerated in Chinese society as symbols of longevity and prosperity, and their antler bones were used in arts and crafts. The snail shells, found everywhere from Hainan Island to Japan to the Philippines, were valued for their pearl-like shine and used in furniture inlays.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4c/c3/4cc320ab-1f5f-457a-87c4-7a67cb159415/8hainan.jpg) A Turbo marmoratus shell from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

A Turbo marmoratus shell from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The Ming dynasty’s ban on maritime trade

The wrecks’ existence is all the more significant due to the widespread ban on sea trade during the Ming dynasty. In 1368, after nearly a century of Mongol rule in China, the Hongwu emperor—the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty—ascended to the throne. Born into a poor peasant family, he began his reign by resetting the clock to year one and issuing an ancestral decree “to promote frugality and constrain luxury.” He would rule through a traditional Confucian way of agriculture before business.

Fun fact: How the Hongwu emperor claimed the throne

- In 1352, the future Hongwu emperor joined a rebel group that fought back against the Mongols. Over the next decade and a half, he rose through the ranks, capturing key cities and eliminating threats to his authority.

- Known as Zhu Yuanzhang, the military leader declared himself the first emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1368, adopting Hongwu as his regnal name.

Material desires and indulgences were curbed. To set an example for his subjects, Hongwu ordered the gold to be stripped from his royal coach. His wife, the Empress Ma, washed the family’s clothes at the palace creek.

The emperor also banned overseas trade. Rocks and pine stakes blockaded harbors, and 450 naval garrisons studded the shores to stop foreign landfall. Violating the absolute ban on foreign sea trade could mean the death penalty, but some smugglers deemed the risk worth it.

The mid-1500s saw an outpouring of Chinese piracy, with sailors like the enslaved outlaw Wu Ping disrupting the high seas. To keep the profits from sea trade rolling, a frenzy of wokou (a Chinese term that translates to “Japanese pirates”) pillaged the east coast of China between 1369 and 1576. Despite their name, the raiders also included Chinese people from landlocked Fujian Province, who needed seafaring to survive. “Pirates and traders are the same people,” said Tang Shu, a provincial officer in Fujian, in 1516. “When trade flourishes, pirates become traders, and when trade is banned, traders become pirates.”

A fahua vase from the Zhengde trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

A fahua vase from the Zhengde trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The deep-sea trader wrecked with porcelain cargo in the South China Sea sailed under the Zhengde emperor, in the early 15th century, when the sea ban first began to be relaxed. Zhengde knew the prohibitions harmed China. But it wasn’t until 1567 that officials lifted the maritime ban. Almost overnight, piracy vanished. At Huzhou in eastern China, Portuguese galleons were crammed with more than 1,000 cases of fine fabrics per ship and sent to Spanish-controlled Manila in the Philippines, the Spanish Empire’s leading trans-Pacific port. A Chinese cargo ship wrecked in 1580 and discovered off the coast of Indonesia in 2010 is believed to hold a staggering 500,000 artifacts, chiefly Chinese porcelain.

To feed the West’s obsession with porcelain, some one million souls worked day and night at 3,000 kilns in smoky Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi Province. As the imperial scholar Wang Shimou put it in the late 16th century, “Tens of thousands of pestles shake the ground with their noise. The heavens are alight with the glare from the fires, so that one cannot sleep at night. The place has been called, in jest, ‘The Town of Year-Round Thunder and Lightning.’”

The rise of maritime trade under the Song dynasty

While the Ming dynasty resonated in the West as an age of great enlightenment (Ming literally means “bright”), it was under a predecessor, the Song dynasty, that the greatest leap in China’s maritime history took place.

In the mid-12th century, inflation spiked due to the loss of northern China to Jurchen horsemen. The Song government went bankrupt after spending the vast majority of its yearly revenue on the military. Desperate action was needed to create a new order out of the wreckage of the old. The answer lay beyond the Great Wall, in maritime trade.

A storage jar from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

A storage jar from the Hongzhi trader

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Under the Emperor Zhezong, between 1085 and 1100, 600 ships were built annually. By 1259, the city of Ningbo alone was home to nearly 8,000 junks and fishing boats. Song ships sailed with game-changing technology, particularly the south-pointing needle compass that appeared earlier in China than it did in the West. The Song dynasty scholar Wu Tzu-Mu knew that for ships leaving the imperial silk factories of Hangzhou, the sea was “the abode of mysterious dragons and marvelous serpents. At times of storm and darkness, they travel trusting to the compass alone. … If there is a small error, you will be buried in the belly of a shark.”

The Italian merchant Marco Polo saw firsthand how the new breed of ocean junk, built with up to 60 cabins for merchants’ privacy and crewed by as many as 300 sailors, had space for the equivalent of 6,000 baskets of black pepper. By the late 11th century, up to 13 watertight compartments in a single ship stopped delicate goods from spoiling. The technology was more reminiscent of the supposedly “unsinkable” Titanic than the medieval world.

The West only caught on to this knowledge in the 1780s, when Benjamin Franklin suggested in a letter that Westerners adopt the Chinese practice of dividing “the hold of a great ship into a number of separate chambers by partitions, tight caulked, so that if a leak should spring in one of them, the others are not affected by it.” England claimed the invention of the watertight bulkhead as the brilliance of Sir Samuel Bentham in 1795; the engineer’s wife later admitted that his eureka moment was borrowed from the boats he saw along the Shilka River on Russia’s border with northeast China.

Trove of porcelain pieces recovered from over 700-year-old shipwreck in waters of Chinese coast

A wreck featured prominently in the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea shows how the technology was pioneered in Song China 750 years before the Titanic set sail. Known as the Huaguangjiao One wreck, the ship probably began its final voyage around 1162, in the port of Quanzhou in Fujian, the start of the Maritime Silk Road during the Song dynasty. Quanzhou was home to an estimated 200,000 people and was considered by many merchants of the time to be the greatest harbor in the world.

During its journey, the Chinese junk found itself trapped among the Xisha Islands, known by Europeans as the Paracel Islands. The labyrinth of small islands, reefs and sandbanks in the South China Sea was notorious by the 17th century as “dangerous ground” for wrecking Western ships.

The junk spiked its keel on the razor-sharp Huaguang Reef. Piles of ceramics, iron bars, copper goods and coins came to rest at a depth of nearly ten feet. They lay forgotten there for the next eight centuries.

Local fishermen stumbled onto the wreck in 1996. A formal excavation, conducted by marine archaeologists assembled from across China in 2007, eventually recovered more than 10,000 artifacts and 511 wooden hull timbers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/9b/0c9b5a5e-26ed-44d3-8c64-b9a8d230797d/9hainan.jpg) Divers excavate the Huaguangjiao One wreck.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Divers excavate the Huaguangjiao One wreck.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The wreck site, the team discovered, had already been severely damaged. “The site’s surface was scattered with broken porcelain shards and coral concretion,” says Zheng. “Illegal looting had dealt a devastating blow to the site. Bulkheads were pried open, planks torn away and there was even evidence of explosives being used. The looters’ violent methods caused irreversible damage far beyond what could be caused by normal fishing activities like trawling.”

By good fortune, the bottom of the hull survived, pressed against the reef for a length of roughly 55 feet and a width of 23 feet. Careful study brought to life a remarkable story. The keel and bulkheads matched the Fujian style of oceangoing ship, known in the Song dynasty for its hull, which was flat on the top and “sharp as a blade” on the sides, according to Zheng. Fujian junks—built with 80 percent pine wood—were reinforced with five to six layers of planking, which was needed to withstand damage from saltwater clams known as shipworms. The planks were fastened with iron nails and sealed with pine resin. Ten watertight bulkhead compartments boosted the ship’s resistance to sinking, albeit unsuccessfully in this case.

The ship’s cargo of blue-and-white porcelain, celadon and brown-glazed porcelain, bowls, plates, boxes, pots, bottles, jars, and urns represented “inexpensive yet well-made goods,” says Zheng. They “reflect a model of mass-produced, standardized production, indicating that the overseas market at the time was dominated by mass consumption rather than luxury goods.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/86/34866db0-2fbc-425f-944c-ecdddd8df560/11hainan.jpg) Reconstruction of the 12th-century Huaguangjiao One wreck

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

Reconstruction of the 12th-century Huaguangjiao One wreck

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

One key find, a white celadon bowl painted with the words “made by Pan Sanlang in Ren Wu Year,” dated the ship to the 32nd year of the Song Emperor Gaozong’s reign: 1162. This telltale artifact, as well as other objects recovered from the wreck, is proudly displayed in the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea.

The Huaguangjiao One wreck has “milestone significance in the history of Chinese underwater archaeology,” says Zheng. “It is, to date, the only ancient ship in China’s ‘far-sea’ waters to be fully uncovered, mapped, dismantled and recovered by a Chinese team.”

The legacy of the Maritime Silk Road

The wealth of underwater discoveries made in recent years leaves no doubt that China’s maritime influence has long been overlooked. As a Spanish Dominican missionary stationed in China observed in 1669, “There are those who affirm that there are more vessels in China than in all the rest of the known world. This will seem incredible to many Europeans, but I, who have not seen the eighth part of the vessels in China, and have traveled a great part of the world, do look upon it as most certain.”

In antiquity, a single ship could stow more goods than three caravans of camels trudging along the desert Silk Road. When it came to bulk transport and speed, the sea was the only option, as the sprawling cargoes of the deep-sea South China wrecks show. Starting this fall, and continuing over the next three years, China plans to excavate, recover and display some 10,000 additional artifacts from the two wrecks.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/8c/b68cb7a9-babc-41fb-a43d-61c299cd516d/1hainan.jpg) The China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea opened on Hainan Island in 2018.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

The China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea opened on Hainan Island in 2018.

Courtesy of the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea

“A series of major archaeological discoveries and high-profile publicity and exhibitions have captured the public’s attention,” says Zheng. Underwater archaeology, he adds, has transformed “from a mysterious professional field into something accessible. … Shipwrecks and their cargoes of exquisite porcelain and other goods are seen as a microcosm of the prosperous ancient Maritime Silk Road and powerful proof of our ancestors’ development and use of the oceans in the South China Sea and beyond.”

What else remains to be found? According to Zheng, some experts estimate that perhaps 100,000 ships sank off China’s coast after the Song dynasty ended in 1279. More conservative calculations suggest that around 2,000 to 3,000 are preserved as wrecks, ready to resurface for study. “The potential for future discoveries in Chinese underwater archaeology is immense,” Zheng says. And now, with exploration plunging into deep seas, he adds, “This ‘final frontier of archaeology’ holds limitless potential.”

.png)