Not medical advice.

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool."

—Richard Feynman

When children first learn about science in grade school, they’re taught the importance of changing only one variable at a time. You isolate and manipulate a single variable of interest, holding everything else constant. In the modern adult world, professional scientists routinely fail to do things this way, allowing multiple factors to vary between conditions, often without even knowing exactly what all those variables are. Experiments are poorly controlled, and researchers don’t even realize how poorly controlled they are.

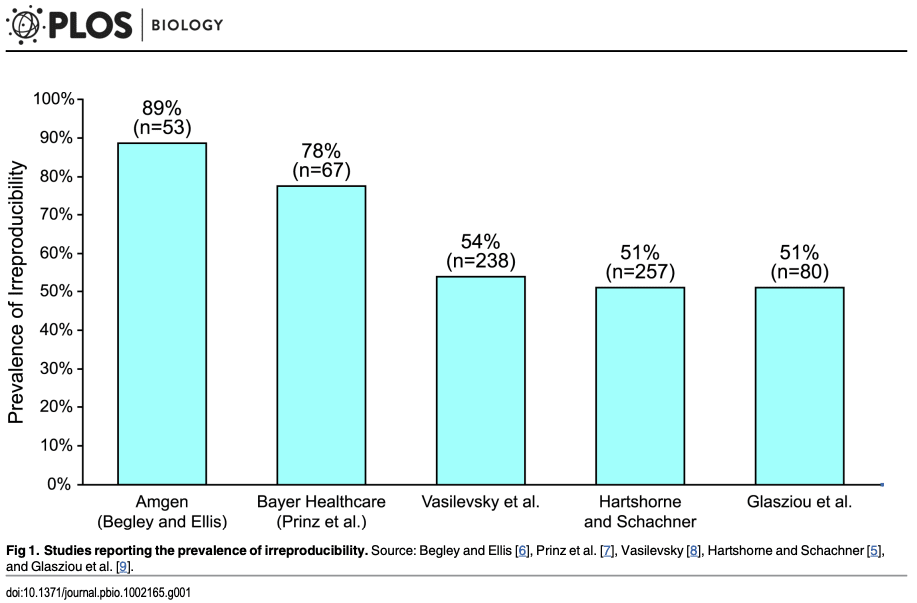

People often point to the reproducibility crisis and lack of rigor in “soft” fields like psychology and the social sciences, but these are also major problems in general, especially in the realm of biology and diet. Even in clinical research, there are “zombie studies” circulating among randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The liturgy of modern institutional Science™ is based in large on this corpus of “gold-standard” RCTs, which sits high up in so-called “hierarchy of evidence” upon which public policy guidelines are built.

Atop the hierarchy are the Official Guidelines, which define the ritual practices and sacred doctrines underlying “medicine,” which is practiced and administered by a special caste of Experts, uniquely qualified to understand the esoteric language of the literature. The most reliable forms of knowledge come from meta-analyses and systematic reviews, in which many studies are compiled, analyzed, and distilled into conclusions backed by “the literature” as a whole, not just a single study.

An implicit assumption operating at every level of this pyramid (the word “faith” comes to mind) is that the published literature is reliable, on average and over time. No single study is perfect, and many individual papers may contain critical flaws. But the sum-total of this general effort, the top of The Pyramid, points in the general direction of Truth. Sacred practices such as peer-review serve as key quality control mechanisms that help ensure The Pyramid is sturdy, resting on firm foundation.

And, of course, scientists are careful truth-seeking creatures. Experiments are carefully crafted. The contents of reagents are dutifully documented. Papers diligently composed. Laboratory principals, peer reviewers, and journal editors—those who control which papers make it into The Pyramid—read and review with rapt attention, filtering out sloppy scholarship or poorly controlled experiments.

… right?

Learn more about how institutional science & public health actually work:

Podcast | How Science Really Works: Meta-Research, Publishing, Reproducibility, Peer Review, Funding | John Ioannidis

Article | The Purpose of (Public Health) Institutions

In the broad field of how diet effects animal biology and metabolic health, it’s common for the effects of two or more diets to be compared. Very often, the control and experimental diets are distinct in more ways than one, each containing a complex mixture of ingredients. However, the experimental diet is often named as if just one of its salient nutritional features is what matters. Common examples include “high-fat” or “low-fiber” diets. Despite their name, these diets usually differ from control diets beyond their fat and fiber content (although you’d be hard-pressed to know that from reading the papers reporting on them).

What’s worse: the results are usually interpreted and reported as if everything can be explained by the one difference they’ve chosen to talk about. It’s common that the scientists reporting the results don’t even realize all the ways their own experimental diets differ from one another. This leads to conclusions like, “A high-fat diet drives such and such change…” which, in many cases, may be completely wrong.

Preclinical animal studies that use and compare the effects of laboratory diets frequently suffer from one or more of the following problems:

Diets differ beyond what is advertised as the key difference between control and experimental diets. One may have higher fat content, but also contain or lack other consequential ingredients. These differences are often unstated or even unknown to the authors.

Diets with the same name are often inconsistent between studies. Although many, many studies examine the effects of “high-fat” diets, there are often major differences in overall fat content or fatty acid profile from one study to the next, apparent only with close scrutiny or special effort to track down the details. Despite this, the effects are usually interpreted and reported as being driven by “high fat.”

Animal diets do not closely resemble the human diets they’re supposed to model. Many animal studies claim to model “Western” diets. Very often, this is vaguely defined as “high-fat, low-fiber,” or something similar. When you examine the details (if they’re even reported), nutrient profiles can be wildly different from the human diet they claim to model, despite similarity in overall fat content or some other generic parameter.

The authors of the study don’t even know exactly what the diets contain. Yes, you read that right. More than once I have asked scientists on my podcast to describe the experimental diets used in their own work, and they have little idea what they contain beyond “higher in fat” or whatever.

For decades, thousands of preclinical studies have been published that suffer from one or more of these problems. As a result, we’re faced with a huge corpus of poorly controlled studies—studies published in peer-reviewed journals, written with confidence, and filled with jargon—that have nonetheless made it into The Pyramid. Many have been fooled into thinking we know more about the effects of different diets and specific nutrients than we actually do.

The preclinical literature is not the only problem. Entire fields like nutrition epidemiology are filled with junk. The clinical literature has its own problems, such as studies that are under-powered, don’t last enough, and so on. All of this contributes to why exaggerated claims and outright falsehoods make into medical textbooks and guide public policy, from the cultish belief that cholesterol = heart disease to the long-standing myth that high-protein diets are bad for kidney health.

What are experimental animals fed in the lab, and how do scientists model things like the “Western-style” diet? What do terms like this and “high-fat” actually mean, and is this language consistently applied across studies?

Let’s get a sense for how these things are discussed and reported in the scientific literature, and compare it to what we know about the composition of the average human diet in America. We will then use a recently published high-profile diet study, discussed in M&M 240, as an exemplar of scholarship in “diet science,” and why we should not be surprised that we are facing a reproducibility crisis.

Our goal here is not to walk away with any real insight into how dietary composition affects metabolic health. Instead, the purpose of this post is to gain insight into how diet science is conducted in practice—to understand how human social psychology and the incentive structures of institutional Science™ shape how diet science is practiced and published, and why its findings rest on a much shakier foundation than we might like to believe…

Learn more about how medical myths are perpetuated in modern society:

Article | The Cholesterol Cult & Heart Mafia: How the process of science evolves into The Science™ of public policy

Article | Mythology, Medicine & Backwards Nephrology

Article | Scientific Junk Food: A brief dissection of nutritional epidemiology

Lab rodents are usually fed some kind of “chow,” pellets made from minimally processed agricultural products like grains, soybean meal, fish meal, etc. It includes added vitamins and minerals but varies in nutrient content depending on ingredient sourcing. This type of food displays batch-to-batch variation in its precise composition, making it a poor choice for studies seeking to understand the effects of specific nutrients.

The contents of a common laboratory rodent diet:

There are also purified diets made from highly refined, specific ingredients. Each component is precisely defined (according to manufacturers), ensuring consistent nutrient profiles. Purified diets are appropriate when researchers want to manipulate and study the effects of individual nutrients.

(Side note: I am unaware if anyone has ever independently verified the nutritional content of manufactured lab diets. If this happens at all, it probably doesn’t happen very often.)

Despite the fact that purified diets are less variable and more precisely formulated, diet studies often use standard rodent chows. This can easily generate confusion. For example, one diet might have much higher fat and lower carbohydrate than other, leading researchers to report results as being driven by that particular macronutrient difference. However, the two diets can and often do differ in other respects, which the researchers may or may not be aware of.

In this article, we unpacked a recent paper illustrating how easy it is to fool yourself when looking at diet studies that use one or more non-purified diets. In that paper, a purified ketogenic diet was compared to a non-ketogenic chow. Already known was that a ketogenic diet is associated with enhanced effects of certain anti-cancer drugs, leading to the presumption that the effect must have something to do with the “keto-ness” of the diet (macronutrient profile)—after all, that’s the most salient difference between the keto and non-keto diets.

As it turns out, the effect has nothing to do with macronutrients. The same anti-cancer drug effect is seen with a purified high-carb diet. The effect depends on microbial metabolism of a specific soy ingredient, which was present in non-purified rodent chow but absent from both purified ketogenic and purified high-carb diets. This only became clear when researchers isolated and manipulated the right variable, instead of assuming that the most obvious difference between two diets is what mattered.

Many diet studies fail to isolate and manipulate one variable. Lots of studies out there have tenuous conclusions, many of which are probably just plain wrong.

Here’s the thing: most of those studies are never replicated with a greater degree of control over dietary formulations. Nonetheless, they get cited by other papers that tacitly assume the conclusions are valid. Thus, effects attributed to some vaguely define rodent diet, such as “high-fat” or “low-fiber” or whatever, are perpetuated and reinforced within the literature, even though they’re never truly proven. In turn, this research collectively informs which future projects gets funded (or not), using our tax dollars.

But isn’t the enterprise of science structured in a way that reliably brings us closer to truth over time? Don’t we have mechanisms and norms in place, such as peer review, that help ensure that only the most rigorous work gets published in top-tier journals, and that we don’t end up fooling ourselves?

Do scientists, um, even read their own papers carefully?

Why does so much poorly controlled work, which fails to adhere to basic principles of scientific practice that we teach children, get published in peer-reviewed journals?

The key to understanding this is evolutionary social psychology, not some philosophical ideal about what science is supposed to look like in the abstract. How does science actually operate, as practiced by flesh-and-blood human beings with self-interested motives?

Humans are status-seeking primates competing for position within social status hierarchies. Cultural institutions constrain and pattern how and why status is allocated. In the abstract, science is a process aimed at seeking truth about the natural world. But the practice of science cannot be disembodied from the apes that practice it: people who want grants, tenure, and notoriety.

To acquire higher status within institutional Science™, one must publish papers. If you publish papers in name-brand journals that get cited, you will likely acquire higher status, whether or not your methods are reproducible or accurately model reality.

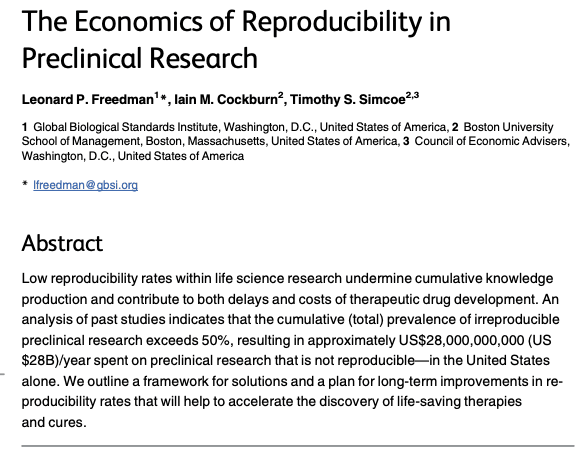

This is why we have a “reproducibility crisis” and spend billions of dollars per year on irreproducible research. The incentive structures of institutional Science™ are geared toward publishing papers, not generating reproducible results. So that’s what we get. “The purpose of a system is what it does.“

What institutional Science™ does is churn out as many journal papers as possible. For a deeper dive into the incentive structures that explain this behavior, listen to M&M 212 With Dr. John Ioannidis. The short answer for why publishing papers at all costs is the name of the game, even if that cost includes reproducibility, is this:

Which is why we observe things like this:

With all this in mind, let’s look at some newly published diet research in a sexy, name-brand journal. This study claims to model a “Western-style” diet. As we’ll see, the precise contents are only partially spelled out in the paper (par for the course in diet science). What started as simple curiosity—Wow, this looks cool. I wonder what the specifics of the diets are?—ended up sending me down an infuriating rabbit hole.

Modern society trains us to trust “experts.” Especially when it comes to health and medicine, things are supposed to be evidence-based. Knowledge comes from credentialed experts who are uniquely qualified to interpret the evidence and tell regular folks what it means. Academic credentials are supposedly reliable indicators of what, and who, we should trust. Who should we trust about the effects of diet on health? Well, the MDs and PhDs who do diet research at major universities and research institutions. Duh!

But what happens when the credentialed experts themselves can’t provide detailed answers to basic questions about their own work? What if their own published papers are contradicted by what’s printed in other published papers, that they themselves authored? What if, with a little digging, you discover that “the same” diets used by labs across studies have actually changed over time, this is never reported, and the researchers using them may not even aware how their reagents have changed?

The diet literature is filled with vague concepts and fuzzy terminology, such as “Western-style” diet. Let’s next examine this concept, and try to get a sense for how closely the preclinical “Western-style” diets actually resembles the American food supply.

Learn more about how scientific publishing, funding, and research actually work:

Podcast: How Science Really Works: Meta-Research, Publishing, Reproducibility, Peer Review, Funding | John Ioannidis | 212

Podcast: Scientific Publishing & the Business of Science | Michael Eisen

Article: How To Read Any Scientific Paper For Free

In general, you will see the “Western-style” Diet (WD) defined as having some or all of the features below. Other variations, such as “Standard American Diet (SAD),” are also used. I will use “Western-style Diet” (WD) as a generic catchall term for preclinical research diets which claim to model the basic diet common in America and the “Western world” that we associate with chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and so forth.

This is one of those things where everybody uses terms like this and we all think we know what it means, but there’s no real precision and terms are used inconsistently.

It’s important to emphasize that this is how WD is talked about in the literature. When using such terms, people are often sneaking in a mixture of vague concepts, odd definitions, and contradictions. I’ll make note of some of the more common weirdness I’ve noticed.

High in Processed Foods: Packaged snacks, fast food, ready-to-eat meals.

I don’t have much to say here, except that there’s no strict, universal definition for terms like “processed” or “ultra-processed.” We can all agree that a box of Gushers are “ultra-processed,” but where, exactly, do we draw our lines? Is a can of beans processed? Ultra-processed? What about fruit that’s been sliced up into pieces? Talking about this stuff reminds me of that famous court case about obscenity laws where a judge was asked to define “hardcore pornography”. His response was, ”I know it when I see it.”

High in Added Sugars: Found in many processed foods, with additional sugars added in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, etc.

There’s lots of added sugar in the processed foods common in the West, no doubt about it. Is it just a matter of volume? What about “complex” carbohydrates that get broken down into sugar within the body? Does the glucose-fructose ratio matter? Do artificial sweeteners count? These types of question often go unstated and unanswered by people who emphasize the high sugar content of “Western” diets.

High in Fat: This usually means high saturated fats (e.g., from meat, butter, etc.) and trans fats (e.g., in fried foods, baked goods).

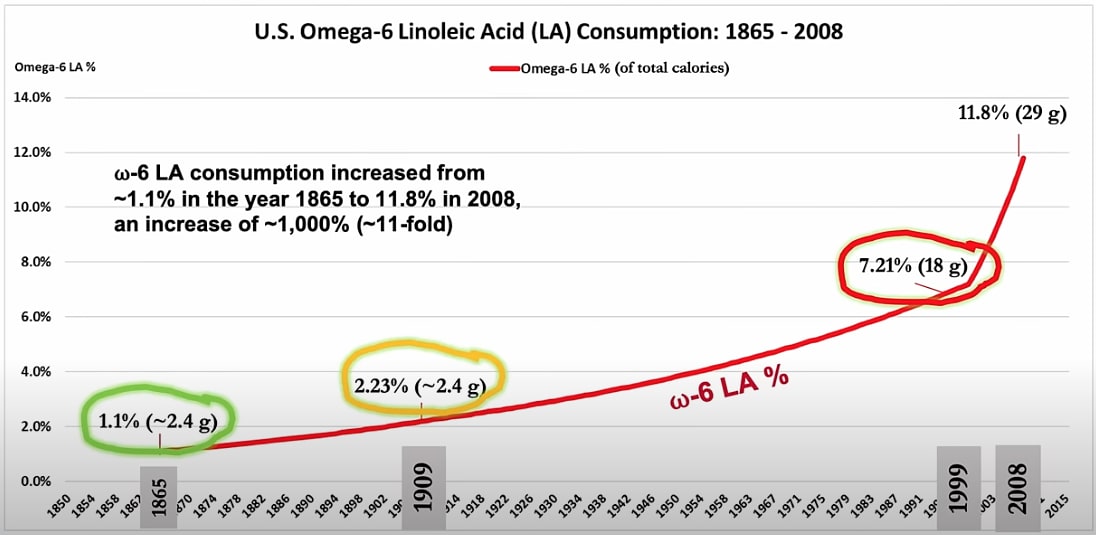

Despite the disproportionate rise in PUFA content in the food supply over time, many people mindlessly associate WD with “bad fat,” which they equate with saturated fat. This is largely an artifact of decades-long campaigns to demonize saturated fats and market PUFAs as “heart healthy.” I’m not saying making any specific claims here, just pointing out that it’s very weird that even scientists who use “Western-style” diets in their own labs often know shockingly little about the fatty acid profile of the average Americans’ diet (as we’ll see below).

Low in Nutrient-Dense Foods: Limited intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and legumes.

Many people and mainstream sources simply define those foods to be “nutrient-dense.” Why is this odd? Well, many have relatively low nutrient bioavailability, despite their “density.” In addition, foods rich in highly bioavailable nutrients, like many animal products, are usually not counted as nutrient-dense. Beans and whole-grain bread are categorized as “nutrient dense,” but not eggs or grass-fed beef. There is no principled reason for this. As far as I can tell, “nutrient-dense foods” generally means little more than, “Anything in the official dietary guidelines that The Experts want to encourage consumption of, as long as it contains some vitamins and minerals.”

Also, have you looked at the nutrition facts of packaged foods in grocery stores? Of course you have. I have, too. Many of them are fortified with lots of vitamins and minerals. Blanket statements like, “processed foods don’t have enough vitamins,” are also a bit weird. Lots of processed foods are loaded with lots of vitamins and minerals. The question of whether that nutrition is bioavailable is another story, which just brings us back to the point above: why are vegetables “nutrient dense,” but not eggs? Cucumbers are vegetables. Go look up nutrient content of cucumbers vs. eggs.

High in Refined Grains: White bread, pasta, and rice dominate over whole-grain alternatives.

True enough—the average American does eat a lot of refined grains. But how true is it that Americans’ aren’t eating enough, “whole grains”? Everywhere I go I see all kinds of “whole grain” products available, with plenty of people buying them. Like, a lot.

Moderate to High in Animal Products: Heavy reliance on meat, dairy, and eggs, often processed (e.g., bacon, cheese).

“Meat” and “animal products” are often used as if any and all animal-based foods have the same basic nutrition profile, which is self-evidently ridiculous. Much of the junk epidemiology out there that associates “meat” with unhealthy outcomes mindlessly lumps together everything with any animal meat, from McDonald’s chicken sandwiches to pasture-raised beef. It’s all “meat.” The nutrient content of factory-farmed chickens fed soybean meal is very different from the grass-fed beef I eat regularly. These things are obviously not equivalent, but much of the mainstream expert class talks about “meat” and “animal products” as if it’s all nutritionally interchangeable. Totally stupid.

Low in Fiber: Due to minimal consumption of whole plant foods.

No doubt, there are plenty of processed junk foods out there with little to no fiber. But I see high-fiber products all over the place, with heavy marketing and lots of people eating them. I know minimally health conscious people who are visibly unhealthy that consume high-fiber breakfast cereals, breads, etc. on a daily basis. I should look into this more, because when I look around I see lots of ordinary and unhealthy people eating quite a bit of fiber.

The above list of “Western-style” attributes can more or less be boiled down to the core features listed just below. As a reminder: we’re talking about the attributes that are consistently associated with this term, as talked about in the diet literature generally. We are not trying to construct our own, ironclad definition.

Calorie dense—the “Western” diet simply has lots of calories.

High fat—“bad fat” is emphasized, which is always equated with saturated fats (and trans fats, which everyone agrees are highly toxic and should always be minimized).

Nutrient poor—this is made as a blanket statement, but often emphasizes low fiber content specifically.

Again, you will immediately run into lots of conceptual weirdness when you start asking basic, common sense questions. The point is that when researchers say things like “Western-style diet,” the bullet points above are all they really mean. And I do mean those vague bullet points. There is not some “expert definition” that’s too technical and sophisticated for peasants to understand, and they’re just dumbing things down for us. How do I know? Because I’ve asked quite a few of them on the podcast, and I read the literature often.

If “Western-style” diet is going to mean anything, and researchers wish to model it in lab animals, we should know what the macronutrient profile of the American food supply actually looks like. There is more to diet than total fat, total carb, and total protein, but preclinical studies should at least be in the right ballpark with these things if they’re claiming to model a “Western-style” diet, right?

This is a low bar, but we have to start somewhere. As we’ll see, even high-profile diet research, published in top science journals, does not meet this incredibly low bar…

I’ve discussed the macronutrient composition of the American diet at length, both on the podcast and in written content. The basic answer in terms of calorie percentages is listed below, based on data for the US food supply.

If “Western-style diet” (WD) is going to mean anything, it should roughly align with the macronutrient profile of the American food supply. If the so-called “Western-style” diet is primarily characterized by high fat content, how much fat are we talking, exactly? And is it really mostly “bad” saturated fat? How much, exactly?

Carbohydrate: 40% or more of calories, often >50%

WD is often described as “high-fat” despite the fact that carbohydrate is the most-consumed macronutrient class in America.

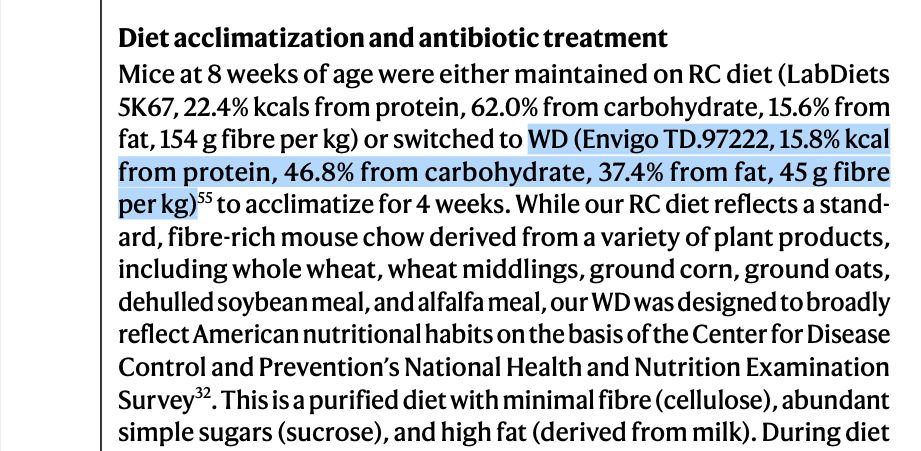

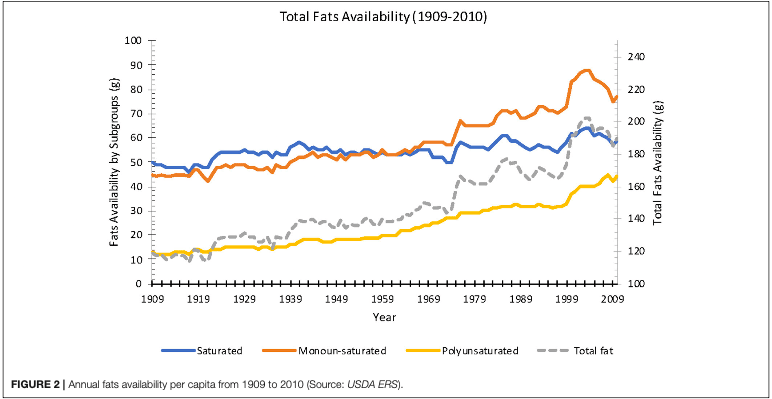

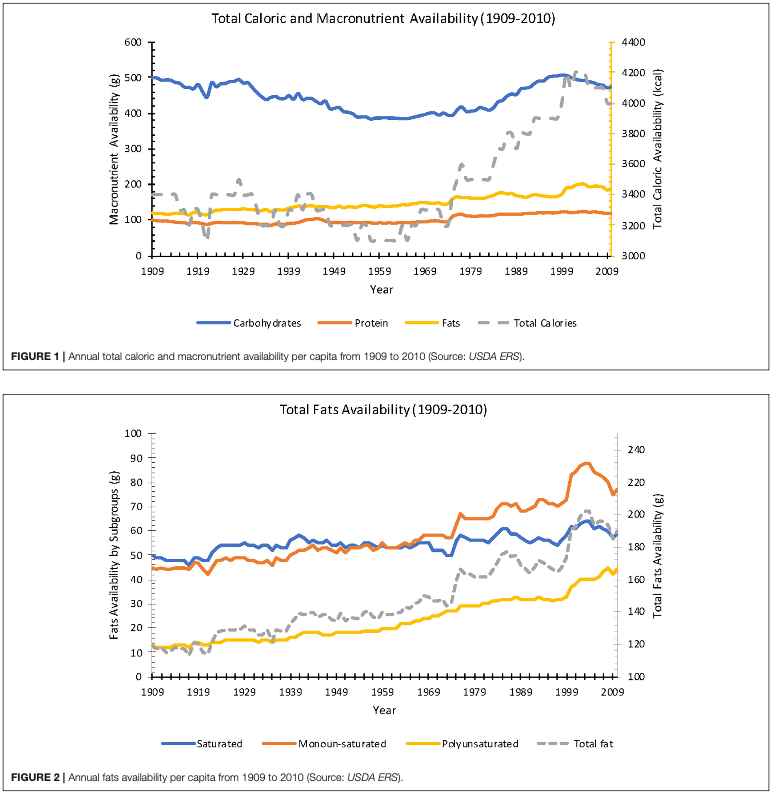

Fat: 30% or more of calories, often ~35-45%

Although the saturated fat content of WD is emphasized, monounsaturated fat has been more widely available since the late 1960s, and PUFAs have become proportionally more common over time, continuing to rise since the 2000s despite a drop in saturated and monounsaturated fat.

Protein: Steady at roughly ~15-17% of calories

Protein intake has been steady compared to carb and fat intake.

A couple charts to give a sense for how the American food supply has changed over time (for more detail, read this):

Learn more about the macronutrient content of the American diet and how it’s changed over time:

Article: Eating Fat Like Never Before

Article: Carbohydrate:Fat Ratios in Fat Gain & Obesity

Podcast: History of Diet Trends & Medical Advice in the US, Fat & Cholesterol, Seed Oils, Processed Food, Ketogenic Diet, Can We Trust Public Health Institutions? | Orrin Devinsky

Again, the “Western-style” diet is said to be high in fat, especially saturated fat. This is repeated and emphasized ad nauseam despite the fact that Americans eat more carbohydrate than fat, and have been replacing saturated animals fats with unsaturated plant fats for decades.

I could go on and on.

The key is that if “Western-style diet” (WD) is going to mean anything at all, it should mean roughly 35-50% of calories from carbohydrate and fat each, with somewhat more carbs than fat, and protein intake somewhat below 20%. As described in this article, the carb:fat ratio of the American diet has been in the 1.2—1.5 range since the 1970s.

Let’s now turn to a specific recent study that claimed to model WD specifically, and leaned into the “high-fat, low-fiber” aspect of what that’s supposed to mean. What was the macronutrient of the “Western-style” diet they used? How does it align with past work from the same authors? How easily could other scientists replicate this work?

As a reminder, this post isn’t about the headline results of the studies we’re about to look at—it is about the language and rigor of this work, and the social-psychological forces that underlie why the institutional Science™ works this way.

Keep that in mind…

In M&M 240, I talked with the senior author of this study published in Nature, the sexiest of all journals. In a truth-driven world, only the highest-quality research would be published in Nature. But we we are not primarily truth-seeking world. Humans are driven by social status, and the currency of status in institutional Science™ is Nature papers. Abstractions like truth and reproducibility are secondary—nice-to-have, but not strictly necessary. Nature papers get you jobs, promotions, and notoriety, whether or not your results are reproducible or robust.

As we go through this work, we want to notice how they define “Western-style diet (WD),” and how that compares to the nutrient content of the animal diet used to model it. How much about these diets are the researchers are even aware of? Are there any discrepancies between this and previously published work, using the same exact lab diet, published by the same people? Could we replicate this work based on the reported methods?

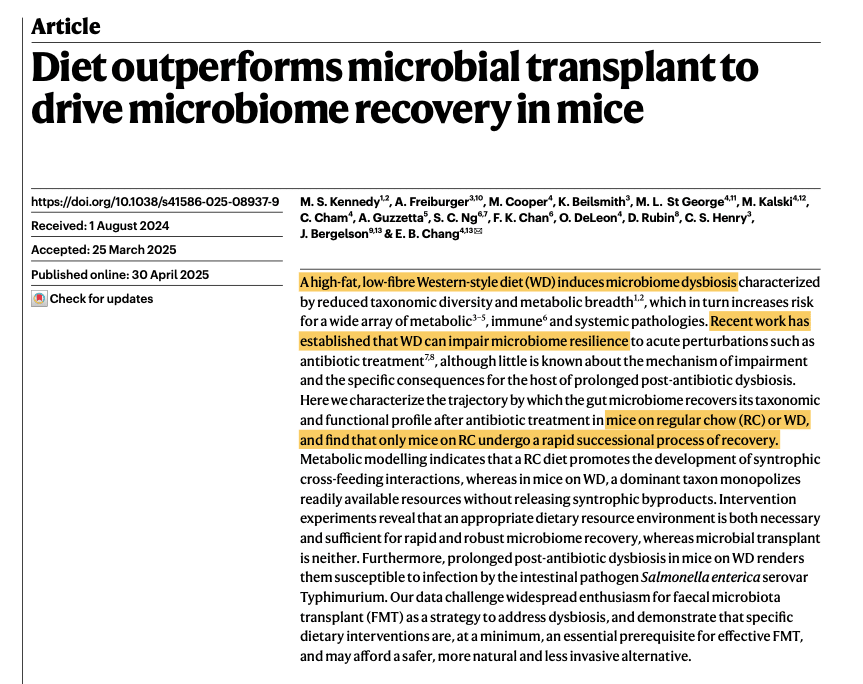

Here’s the study title and abstract. Notice that they are comparing two diets: “regular chow” vs. a purified “high-fat, low-fibre Western-style diet (WD)”. This means that the two diets differ beyond the fat and fiber content emphasized as the key difference. Keep this in mind.

High-fat, low-fiber. High-fat, low-fiber.

This is practically a mantra in “diet science,” and supposedly what is especially bad about the “Western-style” diet. High (saturated) fat and low fiber are mentioned more often, by more researchers, than just about anything else. Specifics of the fatty acid profile are rarely considered beyond, “it’s got lots saturated fat, which is bad fat.” The diets they’re comparing differ in many other ways, but this is often ignored or even completely unknown to the researchers doing the work.

A description of the two diets, from the Methods section of the paper:

“While our RC [regular chow] diet reflects a standard, fibre-rich mouse chow derived from a variety of plant products, including whole wheat, wheat middlings, ground corn, ground oats, dehulled soybean meal, and alfalfa meal, our WD [Western Diet] was designed to broadly reflect American nutritional habits on the basis of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. This is a purified diet with minimal fibre (cellulose), abundant simple sugars (sucrose), and high fat (derived from milk).”

Okay, what about the macronutrient content of the diets. What are the carb, fat, and protein percentages for this “Western-style” mouse diet?

Carbohydrate, 46.8% calories

Fat, 37.4% calories

Protein, 15.8% calories

Notice that this does match pretty well the macronutrient profile of the average American diet we examined above.

So far, so good. But I was curious to know more detail than this…

(Side Note: As a reminder, we are not evaluating the headline results of the above study in this article. If you go through that paper yourself, or listen to M&M 240, keep in mind that the two diets they used differed beyond their macronutrient and fiber content, and so no results can actually be definitively attributed to those factors beyond reasonable doubt.)

If you’ve followed my work before, you will know that specific nutrient profiles matter if you want to understand the metabolic consequences of food. Just knowing the basic macronutrient breakdown is not enough. For example, different fatty acids have different biological effects, so two diets with matched overall fat content can still drive distinct metabolic outcomes. (Similar idea for other nutrient classes).

To learn more, I simply asked the senior author of the study on the podcast.

You might think that the scientist of a high-profile paper about diet, just published in Nature, would be able to tell me specifics about the diet he used in his own diet study, on a podcast scheduled ahead of time specifically to discuss this exact diet paper.

NJ: I want to ask you a little bit more about how “Western diets” are defined and how we model that in preclinical research—different studies use different formulations of diets, and so you really have to look at the specifics. When you say “Western diet,” and when you're modeling it in your studies, what does that mean—exactly—in terms of nutrient composition? It sounds like there is a relatively high fat diet, something like 35-40% of calories from fat, and that a substantial chunk of that fat is saturated fat. Is that part accurate?

EC: That's correct. So we're one of the few groups that actually paid attention to that, right?

[NJ: He is emphasizing here that his research group apparently paid EXTRA attention to diet composition. Remember that as you read on.]

EC: Most groups that had done fat diet studies use 60% lard. That's animal-derived saturated fats. Well, who eats that kind of level of fat? You know, I doubt that most people do. Our diet was designed to mimic the composition of the average American diet, and that's well-published by the NHANES study. So that's what guided us, and the formulation of the diet. You know, how much protein, where it came from, fat and sugars—we wanted 37% saturated fat, so much percent of protein in certain percentages of micronutrients.

[Important Note: Dr. Chang is correct that there is “too much” fat in many high-fat diet studies, in the sense that they contain more fat than the average American diet. However, he equates lard here with saturated fat. This is NOT accurate. The majority of pig fat today is unsaturated fat, not saturated fat.]

[NJ Note: My personal opinion (speculation) of what’s going on here—psychologically—is that Dr. Chang is possessed by the same false cultural biases that emanate from the core of “mainstream health science.” According to that ideology, animal fat = saturated fat = bad fat, a belief deeply entrenched within peoples’ brains. Dr. Chang is simply unaware that the pig fat people eat is NOT mostly saturated fat. It’s plausible he’s never looked into this himself, and has just inherited his belief from the culture he’s embedded in. Again: this is my personal speculation.]

Ok, let’s pause here.

If you’ve ever listened to my podcast, you will know that I’m not in any way a “gotcha!” type of guy. My style is fair and measured. In fact, I sometimes get listener feedback that I am too generous and passive with guests. My questions come from a place of curiosity. I simply wanted to know the details about the diets used in Dr. Chang’s work. (I had no intention ahead of time to write this article. All of this was written in response to what I found after looking into citations in Dr. Chang’s paper, after this exchange; see below).

I wasn’t too surprised by his answer. I’ve asked multiple diet researchers to describe the composition of diets in their diet studies, conducted in their diet labs. The answers they give are rarely more detailed than what Dr. Chang provided, and it’s common for researchers to just say some version of, “The experimental diet was high-fat”.

After the podcast, I went back to the new Nature paper, and looked up the citation for the diet, which took me to another, older study by Dr. Chang.

It was at this point that I became more confused, and ended up going down a rabbit hole. This is where things started to get frustrating/interesting, motivating me to share the story here.

I looked up the diet reference in the Nature paper. In theory, such a citation should bring clarity, leading me to a more detailed description of what the diet used in this study actually contains.

Instead…

The reference brought me to this study, with some of the same authors, listing more details about the high-fat diet (“TD.97222”).

What do you notice?

The Nature paper says the WD diet chow is 46.8% carbs, 15.8% protein. But the paper it cites in reference to this high-fat “Western-style” diet has the opposite printed in the table above: 46.8% protein, 15.8% carbs.

What’s going on?

Well, a 46.8% protein diet would be absurd. I’m not even sure human body-builders eat that much protein. Maybe they do, but certainly not the average American.

My natural thought: this must be a simple typo in the table above. It says that the TD.97222 diet is 46.8% protein and 15.8% carbohydrate, but that’s the product of human error—somebody messed up, and flipped the two numbers. (And the senior author didn’t catch this… and the journal editors didn’t catch it, either. This is “peer-reviewed” research, right?).

But…

Elsewhere in that same paper, it reaffirms that this high milk-fat (MF) diet does indeed contain 15.8% carbohydrate:

“The diets in our study contained comparable amounts of carbohydrates (LF, 13.8% and MF, 15.8%), whereas in Zhang et al.’s study, the amount of carbohydrates in the HFD diets was much lower than in the NC diet (26.3% compared with 61.3%).”

Read that again.

They are not merely re-affirming what we would otherwise assume is a simple typo in the Table 1—that this “high milk-fat” diet (MF), contains 15.8% carbohydrate rather than 46.8%—they are explicitly stating this 15.8% carb level is similar to their control diet, which they say makes this study BETTER than another study that found a different result from what they found.

This can’t be just a simple typo in a table. If it was, then whoever wrote this paper repeated and basically bragged about the macronutrient typo in Table 1 as if it were a strong point of this paper. (Please remember this part, because things get even more stupid below). This more or less means that whoever wrote this had no real idea of what they were talking about, because this is just silly… and that means that the senior author of this paper, multiple colleagues who presumably worked on this, and the reviewers and journal editors who looked at this paper, all missed this glaring and ridiculous piece of writing.

By the way, that 2016 paper has been cited 104 times, including multiple 2025 papers so far. Who, exactly, is carefully reading this literature?

Do you remember the “hierarchy of evidence” pyramid we discussed at the beginning? We’re talking about the base of the Pyramid.

Two mutually exclusive possibilities for the Nature paper:

The new 2025 Nature paper misprinted the macronutrient content of the “Western-style” diet used in the study, which is actually 46.8% protein + 15.8% carbs, and therefore wildly different from the average Americans’ diet.

The Nature paper is accurate, but the paper it cites as a reference for this diet misprinted the macronutrient content—TWICE—once in a table and again in a section of the text explicitly talking about how it has similar carb content to another, low-fat diet (13.8% vs. 15.8%), and everyone who was supposed to have read and understood this paper, failed to notice any of this.

Either way, this is ridiculous. These are peer-reviewed papers in name-brand journals, submitted and reviewed by professional scientists and journal editors. The papers are all about the effects of diets with different nutrient profiles. And yet, in at least one of these journals, the multiple authors and multiple reviewers who allegedly read these things, missed something like this. What?

So, what is the real macronutrient profile of the “high-fat” rodent diet in question? I looked up the TD.97222 again, in another paper, which has this say:

“Mice were provided with either autoclaved normal rodent chow (NC; LabDiet 5k67) or an irradiated semi-purified high-fat diet containing 37.5% anhydrous milk fat (HFD; Envigo Harlan Teklad TD.97222 customized diet).”

It does not provide a reference or tell us anywhere what the actual macronutrient composition is. It’s just, “high-fat” with “milk fat,” whatever that means.

Again, these are diet studies that do not tell us the full composition of the diets they use. We just get vague language like “high-fat,” and citations to other papers which don’t even provide consistent numbers.

Trying my best to Trust the Science here. I’m reading from the base of The Pyramid, and this is what I found. If you take these texts seriously, read their words literally, and follow the citations, this is what you get. Confusion.

I checked more papers that used Envigo TD.97222, but none of those provided the full macronutrient profile, just stating the fat percentage. I did manage to find yet another (third) paper with some of the same authors. It provides this table:

The “SFA (Milk-Fat)” diet is the same diet in question here. Notice that it lists protein at 16% and carbs at 47%. This what the 2025 Nature papers printed, suggesting that the absurd double-misprint thing I described above for the 2016 paper is indeed and absurd double-misprinting that nobody saw or corrected.

Just to be extra super-duper triple sure… I e-mailed Dr. Eugene Chang and just asked him all about this. Here’s what he had to say, as well as exactly what I asked him:

NJ: Dr. Chang,

An important aspect of your work is confusing me. In your new Nature paper (the one we discussed), you list this as a the macronutrient content of your "Western" diet:

Envigo TD.97222, 15.8% kcal from protein, 46.8% from carbohydrate, 37.4% from fat

However, in citation [55] attached to that dietary composition, you cite another one of your papers, which has the protein and carb content flipped--something that appears in both the table below and the text of the paper, and so is apparently NOT a typo?

I am confused.

What is the actual macronutrient composition of the TD.97222. It has been used in many papers, most of which report only it's ~37% fat content, without providing more detail. The only paper which does provide more detail (yours), reports a difference carb + protein content from your Nature paper.

Please clarify.

EC: Thanks for checking, Megan. I have no idea where the first author of the 2016 paper (Adina Howe) is currently. I will try to find out and ask her to notify the journal to make the correction. At this point, I am doubtful anyone cares or even looks at this paper.

[He referred to the following note from his assistant]:

I just checked - I have the correct macronutrient composition listed in the text of my paper, which matches the macronutrient data we got directly from the manufacturer (attached). It also makes more sense that it would be 15% protein 46% carbs since the regular diet is 22% protein 66% carbs - this preserves the protein: carb ratio.

I would imagine in the reference we had cited (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5029215/pdf/ismej2015183a.pdf from our lab in 2016) the authors had created that in-line table by hand and mixed up the carbohydrate and protein values.

So yes, the carb and protein values of the 2016 are indeed mixed up, which makes sense since 47% protein would be absurd. But again: this was not just a simple error in one table. The same paper essentially boasted about the (incorrect) carb content printed in that table—a paper on which Dr. Chang is the senior author, meaning that it was his responsibility to scrutinize and sign-off on before personally aubmitting it to the journal.

As a reminder: this article is about language and the mechanics of institutional science. With that in mind, notice the language that Dr. Chang used in the above e-mail: “At this point, I am doubtful anyone cares or even looks at this paper.”

That paper has been cited over 100 times since 2016, including three citations so far this year—including, of course, the new 2025 Nature paper by Dr. Chang himself (frequent self-citation is common practice in academia).

For those of you paying attention, I am simply documenting how it is nearly impossible to verify diet information from papers about… diet.

There are two reasons why I spent my time down this rabbit hole:

To share with everyone just how absurd the scientific literature can actually be.

I literally spoke to the senior author of these studies on the podcast, fairly and calmly, asking genuine questions of interest—questions like, “What is in the diets you spend your career studying?”—and I could not get anything more than a vague, ‘it’s got lots of fat’ description of it.

In the podcast, Dr. Chang emphasized that his group, more than others, was careful to pick a diet that closely matched the human Western diet. And yes, the total fat content does match. He is rightly pointing out that many other studies use ~60% fat content, which is much higher than the average American’s diet. What he does not seem to understand is that pork fat (lard) in American today contains more unsaturated than saturated fat.

In fact, we can see plainly in the table above, from one of his other papers, that the fat profile of this “Western-style” diet does NOT match the fat profile of the American food supply.

The diet in question here is 58.5% saturated fat, 26.5% MUFA, and 15% PUFA. That is not the fat profile of the American food supply.

Here’s the data of the dietary fat content of the US food supply we looked at above. If anything, it has become more skewed towards PUFAs since the end of this graph:

This fatty acid profile is simply not similar to the experimental diets being called “Western-style” in papers like this. They might be comparable in terms of the carb, fat, and protein ratios, but they are different in terms of fatty acid profile, and many other aspects, apparently unknown to the people doing this work. For crying out loud, they can’t even properly label the macronutrient profiles in a consistent manner across (highly cited) papers, or provide any real detail about dietary composition when talking about this stuff in person.

I mean, come on. We’re talking about researchers who get multi-million dollar grants to study stuff.

Anyways, he explicitly stated that the diet mimics the typical American diet, not just in terms of fat content, but in terms of protein and micronutrients.

So… I asked him to tell me more about the content of this diet, used in the many diet studies he has published based on work done in his diet lab:

NJ: Do you know the carbohydrate and protein content of that diet?

EC: Not off the top of my head, but it is published [NJ: as we saw above, it is indeed published, but the carbohydrate and protein content reported are inconsistent between Dr. Chang’s own studies.]

NJ: But it was specifically designed to mimic the average American?

EC: Yes.

NJ: And are there any other salient features of this modeled “Western-style” diet in terms of micronutrients and other things?

EC: I think we tried to be as close [as possible] to what the average American eats.

I try my best to keep a level head and give people the benefit of the doubt on my podcast. In this case, I had specifically looked into the diets beforehand, and was hoping (and expecting) this credentialed expert, who authored these studies, to provide clarity.

At this point, I was growing somewhat frustrated. Not only was I failing to get clear answers on the macronutrient profile of the diets in these studies, but I discerned that there was confusion on the other side of the conversation about what the fatty acid profile of the average American diet actually is.

I tried asking another way:

NJ: When we model Western-style diets in the lab, we tend to call them “high-fat,” and they tend to have a good amount of saturated fat, as you said. But over time, the class of fats that's increased the most in the West are the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Are those contained in any significant degree in the Western-style diets that you use in your preclinical work?

EC: So in Suzanne Devkota's study [referencing past work, not the study in question], we also looked at polyunsaturated fats. And, you know, polyunsaturated fats are just like dietary fiber. There are different types. If you look at, let's say, olive oil versus palmitate, they're very different. They have different actions on the microbiome, and one is considered very healthy, the other is considered not so healthy. So I believe that just saying, you know, “unsaturated fats are good or bad,” is probably too generalized.

[NJ: Notice that the response does not actually answer the question asked. I wanted to know the PUFA content of the study in question, and he said that other past studies have looked at PUFAs, failing to mention what the PUFA content of the diet in question actually was. My suspicion is that neither he nor any of study authors knows the PUFA content of the diet or how it compares to the American food supply.]

NJ: Isn’t a similar thing true for saturated fats? Aren't there multiple types of saturated fats that have different biological effects? [NJ: this is known and the answer is unequivocally, “Yes.” Not all saturated fats have the same effects, and it’s foolish to talk about this or any other general class of fats as “good” or “bad.” Still, I wanted to know his answer.]

EC: Probably so, yeah. I don't have any evidence to prove or disprove that, but I'm guessing that you know all fats are not the same, right?

I feel bad making an example of one person like this, but come on. If you hold a prestigious institutional research position, use taxpayer money to conduct diet research, and garner attention for publishing Nature papers, you should, um… know what’s in the diets of the diet study you conducted in your diet lab?

For the record, here’s the full nutrient profile of TD.97222, the widely used “Western-style” diet in question, which I had to contact the supplier to obtain:

I certainly don’t expect scientists to have every one of these numbers memorized. But shouldn’t they at least be aware of the major ways in which their “Western-style” animal diets deviate from the composition of what’s consumed by Western humans? After all, that’s what they’re supposed to be modeling, and all of this research is justified by its supposed relevance to human health.

Once again, the high-level macronutrient composition—total carbs, total fat, total protein—does match the American food supply. But no serious scientist who knows anything about biology could possibly think that getting the basic macros right is enough to properly model the Western human diet.

I will leave it to readers to dissect this nutrient profile more thoroughly. For now, let’s just notice the fatty acids profile—the saturated fat, MUFA, and PUFA content—as well as the density of linoleic acid, the most abundant dietary PUFA in the human diet.

As a percentage of total fat, TD.97222 diet is about 62% saturated fat, 29% MUFA, and 4% PUFA. As we saw above, this is nowhere near the fatty acid profile of the American food supply, which contains lower saturated fat levels, higher MUFA, and much higher PUFA. In fact, by some estimates, linoleic acid alone represents over 12% of total calories in the average American human diet. But in the TD.97222 research diet, linoleic acid is just 4% of the total fat mass, and just 0.7% of the total food mass.

If the fatty acid profile is that far off the mark, should we have much faith in everything else?

Learn more about the fatty acid content of the average American diet:

Article | Eating Fat Like Never Before

Podcast | History of Diet Trends & Medical Advice in the US, Fat & Cholesterol, Seed Oils, Processed Food, Ketogenic Diet, Can We Trust Public Health Institutions? | Orrin Devinsky

This is not an isolated incident. Not only are the contents of the diets used in diet research poorly reported on and often unknown to the authors themselves, but they often lack awareness of the specific composition of modern human diets.

As used in the preclinical literature, terms like “Western-style” and “high-fat” are not just vague terms that are usually poorly defined within any given study, but refer to diets that are highly variable between studies. Despite this, the researchers who study the effects of these diets (in genetically inbred non-human animal strains) routinely attribute the main results of their work to the macronutrient composition of their experimental diets, emphasizing things like “high-fat” and “low-fiber” content. As a field, sweeping claims are made about “high-fat, low-fiber” diets, despite all of this inconsistency and poor reporting.

The only reason I stumbled upon the poor scholarship of one tiny corner of this immense literature is that… I looked.

I actually read the Methods of the 2025 Nature paper, spoke to its senior author, and then looked up the citation it provided about the diet it used. I then read that paper, only to discover that—apparently—the people who wrote it, the senior author responsible for reviewing it, and the journal editors and reviewers who are supposed critically evaluate it, did not do so.

From stuff like this, the junk science permeating fields like nutrition epidemiology, all the way up to clinical literature filled some unknown number of zombie studies, the Pyramid of Western institutional Science™ is built upon much shakier foundations than many Experts would have you believe.

As above, so below.

Faith in the Pyramid above is what gave us the de-bunked and widely ridiculed pyramid below, which no one in their right mind takes seriously:

Perhaps it’s time to stop placing so much faith in the Pyramids of institutional Science™.

Read more M&M content about how science & public health works in practice:

.png)