TL;DR

UX debt = design flaws, issues that pile up interest. Like technical debt, but users pay the price.

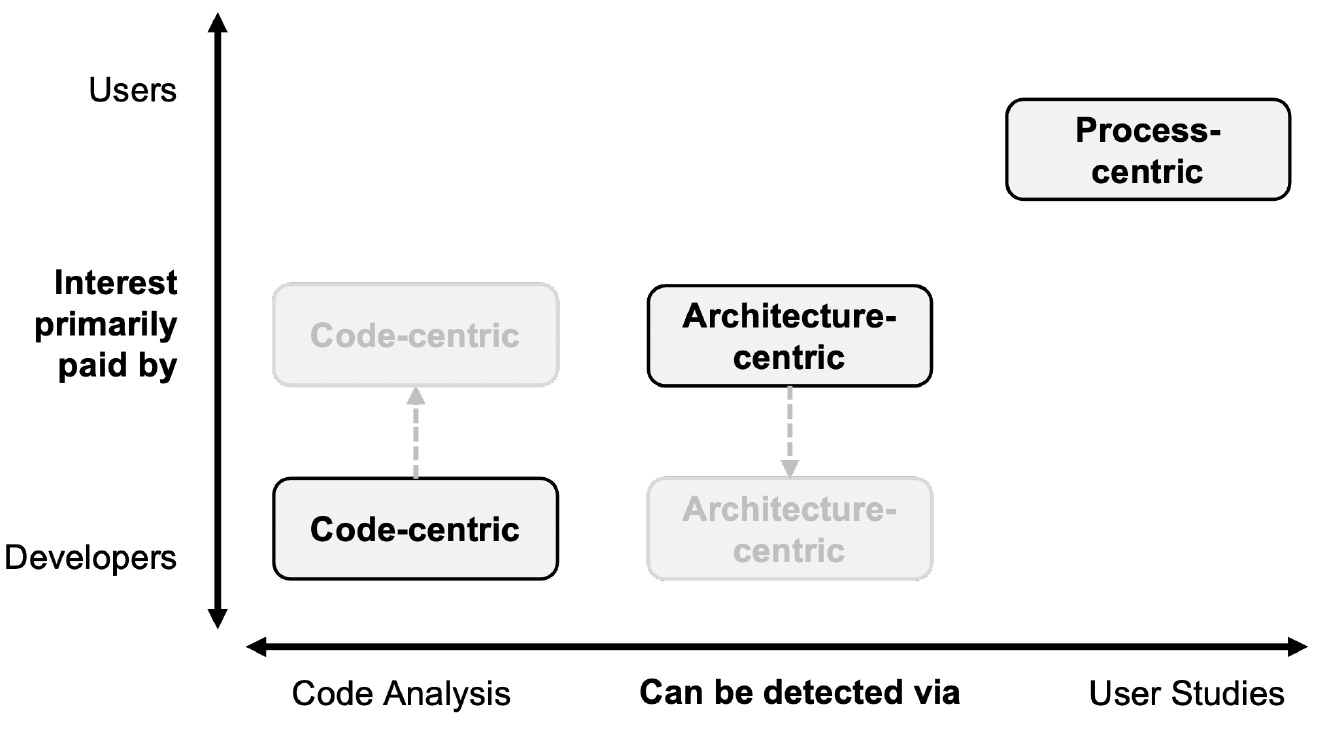

Three classes: Code-centric (duplicate or inconsistent components), Architecture-centric (backend/UI structures that block smooth flows), and Process-centric (product doesn’t match real-world workflows).

Hidden business costs: higher support tickets, slower feature velocity, lost revenue, and even accessibility lawsuits.

Spot it early: heuristic UX audits, analytics (drop-offs, rage clicks), design-system drift checks, and feedback loops with real users.

Pay it down: track UX issues in a debt backlog, enforce a design system, run polish sprints, and give cross-functional teams explicit ownership. The longer you wait, the more your users will pay.

About two years ago, I was part of a team that helped replace a legacy command-line based product onboarding tool for a large e-commerce client with a sleek, modern, multi-page web form. On paper it was a triumph: we slashed the average product listing time from ~24 hours to barely ~20 minutes. Behind the scenes, though, the sprint board told a different story—one littered with bugs, rushed redesigns, screens that drifted from the design system, and workflows that made perfect sense to product owners but left merchants scratching their heads. Design, architecture, and product all lived in separate silos.

The biggest cost, though, wasn’t internal frustration—it was the confusion and friction we unintentionally passed on to our users. Their struggles were symptoms of a deeper issue: accumulated UX debt from rushing to ship fast at the expense of clarity and cohesion. It took a painful but essential overhaul and cross-functional reset before we finally delivered a truly usable product.

In software development, speed often comes at a price. Just as developers talk about technical debt—short-term fixes that incur long-term code maintenance—UX debt refers to shortcuts in user experience design that compromise usability over time.

UX debt is the accumulation of design flaws, usability issues, and inconsistent user experiences resulting from hasty decisions or deferred design work. While technical debt is typically felt by engineers, UX debt impacts users directly. The concept mirrors technical debt, but its consequences are often more subtle and harder to detect.

UX debt directly affects end-users, but its ripple effects spread across teams and organizations. Users encounter usability friction: extra steps to complete tasks, confusion in workflows, or difficulty accessing key features. These issues reduce task success rates, satisfaction, and engagement.

Internally, development teams often pay hidden costs: repeated bug fixes, increased maintenance, and time spent explaining or rationalizing flawed decisions to new team members. Designers patch legacy patterns. Developers implement workarounds for poor design. Product managers lose prioritization clarity when foundational usability is compromised.

UX debt impacts business growth and brand perception. Frustrated users churn. Poor reviews erode trust. Support costs rise. Accessibility violations can even result in legal action. UX debt isn’t just a usability concern—it’s a business liability.

In a study UX Debt: Developers Borrow While Users Pay, Baltes and Dashuber identify three categories of UX debt.

Code-centric UX Debt

This type originates from technical shortcuts that directly impact usability—often through duplicative code or UI components. For example, developers might copy a table or dropdown across the application. Over time, those copies diverge: one version supports filtering, another doesn’t; one is styled correctly, another isn't. These inconsistencies confuse users and increase support overhead. It is the closest analog to traditional technical debt but with an added usability burden for end-users. Though the most visible and measurable, code-centric UX debt is frequently under-addressed because developers focus on functionality, not interface consistency.

Architecture-centric UX Debt

Here, debt emerges from structural decisions that impair the user experience. For instance, an API optimized for backend performance may segment data in ways that hinder frontend flexibility. In one example, frontend teams had to orchestrate multiple backend requests to display a unified view, slowing performance and undermining usability.

In another example, the authors describe how reusable UI container components were architected for clean separation of concerns and encapsulation. While this approach improved code maintainability, it restricted the team’s ability to reposition UI elements to better align with user workflows. The architecture might be technically sound, but it doesn't facilitate an optimal user flow or intuitive arrangement of UI elements. This type of debt is not easily detectable with code analysis tools alone and often requires user research to identify

Process-centric UX Debt

This debt is accumulated due to misalignment between software behavior and real user workflows. It’s rooted in flawed processes—lack of user research, minimal validation, or top-down assumptions. The software may be technically functional but forces users to adapt, rather than adapting to users. Traditional code reviews can’t catch it; only user-centered evaluation methods—usability testing, analytics, interviews can uncover these mismatches.

Without deliberate, ongoing practices to understand user needs, teams risk embedding inefficiencies that cause continuous frustration and, ultimately, user abandonment.

Usability is about people and how they understand and use things, not about technology.

— Steve Krug

UX debt often grows silently. Unlike broken code, a broken experience can be invisible and doesn’t necessarily prevent a product from shipping.

It can be intentional (a conscious tradeoff) or unintentional (stemming from assumptions or lack of time). Intentional UX debt is manageable if tracked and paid down. Unintentional debt is riskier, remains hidden until users push back or churn [1].

Key Contributing Factors:

MVP culture: Teams release early, deferring UX refinement. But "we'll fix it later" often becomes "we never got around to it." in the study, this tendency was observed in teams working under Agile methodologies, where velocity and delivery metrics often outweighed considerations for UX quality. The authors noted that process-centric UX debt frequently stemmed from early design decisions made without sufficient validation, and once initial releases went live, the inertia of subsequent development left little time to revisit and resolve usability gaps.

Design silos: When designers and developers work in isolation, inconsistencies creep in. Fragmented communication leads to uncoordinated reuse and divergent mental models of the user experience.

Lack of UX governance: No shared design standards or reviews. This absence of governance manifests in multiple ways—most notably in the inconsistent reuse of UI components and a lack of accountability for ensuring user-centric outcomes across teams.

Compressed timelines: Usability is sacrificed when delivery deadlines loom.

UX debt become painfully visible in user behavior:

Users may switch to competitor products

Increased task abandonment in critical flows

Low adoption of features due to confusing interactions

Declining satisfaction and engagement metrics

Recurring support tickets for the same UX issues

UX debt weakens trust and brand value. Airbnb cited design debt as a barrier to rolling out improvements. Even simple UI changes, like showing fees upfront, took major internal effort due to accumulated architectural constraints [3].

88 % of online shoppers say they are less likely to return to a site after a single bad experience [4]. That “experience” can be as minor as confusing navigation, slow loading, or inconsistent interactions. In practice, this means companies rarely get a second chance; each friction point compounds churn, raises acquisition costs, and hands competitors an open door.

Unlike tech debt, UX debt requires qualitative detection. But it can still be tracked:

UX audits: Heuristic evaluations and expert reviews highlight friction points.

Analytics: High drop-offs, rage clicks, or long task durations are warning signs.

Support trends: Repeated user complaints may signal underlying UX flaws.

Design system audits: Look for redundant or divergent component patterns.

For quick hygiene checks, use SonarQube with the CSS duplication rule enabled. It surfaces copy-pasted styles before they drift apart and confuse users. Pair that with Stylelint’s no-duplicate-selectors rule on every pull request; the linter blocks fresh clones from sneaking back in once you’ve refactored.

Design systems: Create shared UI languages to ensure consistency. Gradually update legacy UI to current design system standards.

UX debt backlogs: Track usability issues like tech debt. Prioritize based on user impact. A recent academic work proposes the concept of UX smells, analogous to code smells. These are recurring UX anti-patterns (e.g., missing feedback, inconsistent labels) that may indicate deeper usability flaws [2].

Walk the workflow – Run quick tests with real users to uncover workflow friction then storyboard the end-to-end task before committing to screens.

UX education: Train developers and PMs in usability and accessibility principles.

Governance roles: Assign design leads or DesignOps to uphold standards.

Polish sprints: Dedicate time to refining the interface and fixing friction.

Despite its impact, UX debt often goes untracked.

Low visibility: Unlike bugs or crashes, UX flaws aren't always flagged.

Ambiguous ownership: UX debt cuts across design, engineering, and product.

Short-termism: Teams prioritize shippable features over long-term coherence.

Measurement gaps: Many teams lack maturity in UX analytics or usability benchmarking.

To elevate its importance, UX debt must be framed as product quality debt. Just as engineers advocate for refactoring code, UX leaders must argue for addressing design debt as essential to long-term product value.

As a UI architect, I’ve seen UX debt grow quietly—then explode. But I’ve also seen the payoff when teams reduce it: smoother experiences, maintainable codebases, happier users.

By naming and addressing UX debt as a real liability, we can manage it deliberately. Whether through design systems, audits, backlogs, or even AI-driven pattern detection, every team can take steps to reduce it.

The payoff is clear: a streamlined user experience, better team velocity, and stronger product in the market.

A product with low UX debt is like a well-oiled machine—it runs efficiently and delights users, allowing teams to innovate rather than firefight. Because the longer you leave UX debt, the more your users will pay.

References

Baltes, S., & Dashuber, V. (2024). UX Debt: Developers Borrow While Users Pay. CHASE 2024 - . https://doi.org/10.1145/3641822.3641869

Jaspan, C., & Green, C. (2023). UX Smells and Design Debt - https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10109339

Airbnb Design Update. (2023) - https://www.fastcompany.com/90890098/airbnb-fixing-core-design-problems-says-ceo-brian-chesky

Website user experience: How to convert customers and get them to visit again - Google Business

.png)