In September 1781, Thomas Hughes, then 22, visited Brighton for what he hoped would be a restorative holiday. It was not his first trip: such sojourns were common for Hughes. But on this occasion something was different. As Hughes recorded in his journal, ‘launched into a sea of gaiety and dissipation’ he nevertheless felt ‘out of my element’. Though he admitted to being naturally of a somewhat ‘reserved disposition’, this had never previously stopped the young man from enjoying polite company. But as he wandered among Brighton’s gaming tables and ballrooms, he found ‘little pleasure in a concourse of people whose only amusement was the exhibition of their sweet persons and a laborious attendance on the toilette’.

What had happened to Hughes? Why did he feel alienated by pleasures and pastimes that he had once enjoyed? The answer was that he had spent the previous five years as a British soldier fighting in the American Revolutionary War, some 3,000 miles away in an environment which, it had seemed, was determined to destroy him. And, he reckoned, the American wilderness had accomplished its aim with gusto. Arriving in Brighton two months after returning from America, where he had endured bloody battles, months of captivity as a prisoner of war, bouts of disease, and lingering thoughts of suicide, Hughes realised that his ‘long stay’ had ‘quite rusticated’ him: ‘I have never enjoyed my health since my return from America.’ He spent much of his time in Brighton on ‘solitary morning walks on the side of the sea’, where he may well have looked west, towards the land across the Atlantic which, he felt, had irrevocably altered his constitution.

Hughes was one of around 80,000 British and Hessian soldiers who served in the American Revolutionary War between 1775 and 1783. British volunteer corps and their German Hessian conscript allies (hired as mercenaries by the British from the Principality of Hesse-Kassel) arrived in America shortly after the outbreak of war. Although their enemies were ostensibly the American rebels, over the following eight years many of the foreign troops would come to see their military foes as just one of the New World’s many hostile forces. The American environment – its physical terrain, flora, fauna, weather, climate, and diseases – proved hugely detrimental to their physical and mental health. They were not the first European soldiers to discover that a war in America was also a war against the natural world. As one British veteran of the French and Indian War (1754-63) had opined: ‘Those who have only experienced the severities and dangers of a campaign in Europe, can scarcely form an idea of what is to be done and endured in an American war.’ Over the course of the Revolutionary War, anxieties about what the soldiers would face in America would be steadily supplemented by the harsh realities on the ground. Hughes was able to reflect on his experiences in America after his return home; many of his comrades were not so lucky.

Into the swamp

Of all the environmental challenges that British and Hessian soldiers endured during the war, the continent’s flora and fauna elicited some of the strongest complaints. In a sense, these had been integral to the British Empire’s American landgrab. Cows, horses, and pigs had served alongside the colonists as agents of empire, pushing back the frontier. Cash crops such as tobacco, indigo, rice, and sugar had proven hugely profitable.

But while it was possible to admire America’s natural produce from afar – perhaps by toasting the fortunes of empire while smoking a pipe of American tobacco and enjoying a bowl of West Indian punch in a London tavern – the soldiers sent to fight the rebels enjoyed no such luxury. By the time the troops stepped foot on American terra firma they had already endured a transatlantic journey that could take up to three months. One Hessian soldier recalled that: ‘My continued misfortunes and the constant dangers of the long voyage ... had worn me down so much that both life and death seemed like prizes to me.’

But even after arriving in America, terra firma could not be taken for granted. In the accounts of the European soldiers who endured the Revolutionary War, America’s vast swamplands recur as a particular source of misery. In October 1779 Lieutenant John Enys found the hardships of marching through New York’s ‘Great Swamp’ ‘impossible to conceive’. While Enys considered the swamps of New York ‘disagreeable’ and ‘uncertain’, he was relatively lucky: his comrades stationed in the war’s southern theatre (comprising Virginia, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Florida) encountered far larger, more dangerous swamps, where the natural dangers were exacerbated by the presence of rebel foes who knew how to use the environs for their own benefit. The American soldier Francis Marion became known as the ‘Swamp Fox’ due to his ability to wage guerrilla warfare against the British forces during their invasion of the Carolinas in 1780 and 1781. Frustrated at his troops’ slow progress, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart confided to his commanding officer, Lord Cornwallis, that Marion had rendered any intelligence of the rebels’ strategic position ‘impossible by waylaying the bypaths and passes through different swamps’. Covering some 750 square miles across Virginia and North Carolina, the ‘Great Dismal Swamp’ is thought to have acquired its evocative name in 1728 when the British-educated Virginian surveyor William Byrd II traversed its wetlands in an attempt to establish a boundary between the two states. During the war it proved the most daunting of America’s swamps, described by the Scottish major J.F.D. Smyth as ‘the principal of all those dreadful places, called swamps, only to be met with in America, for there is nothing of the kind to be found in all Europe, Asia, or Africa’.

It was true that most of the European soldiers had not experienced anything like an American swamp. There were wetlands in Britain, such as the Fens, and some Hessian soldiers may have known the Elbe marshes, but both paled in comparison to America’s vast wetlands. One (contested) version of the etymology of the English word swamp locates its earliest usage in early 17th-century North America. Though the word was probably in use before this, the soldier’s understanding of what a swamp was – or could be – would have been radically altered by their experiences, especially in the south, where swamps had forbidding names such as the ‘Black Swamp’ and the ‘Devil’s Elbow’. From the reflections of those soldiers we can build a picture of what it was like to experience the swamp: black water, festering mud, stifling heat, strange, thick trees and ferns, and, in the worst case scenario, the possibility of an encounter with an apex predator.

Beasts of prey

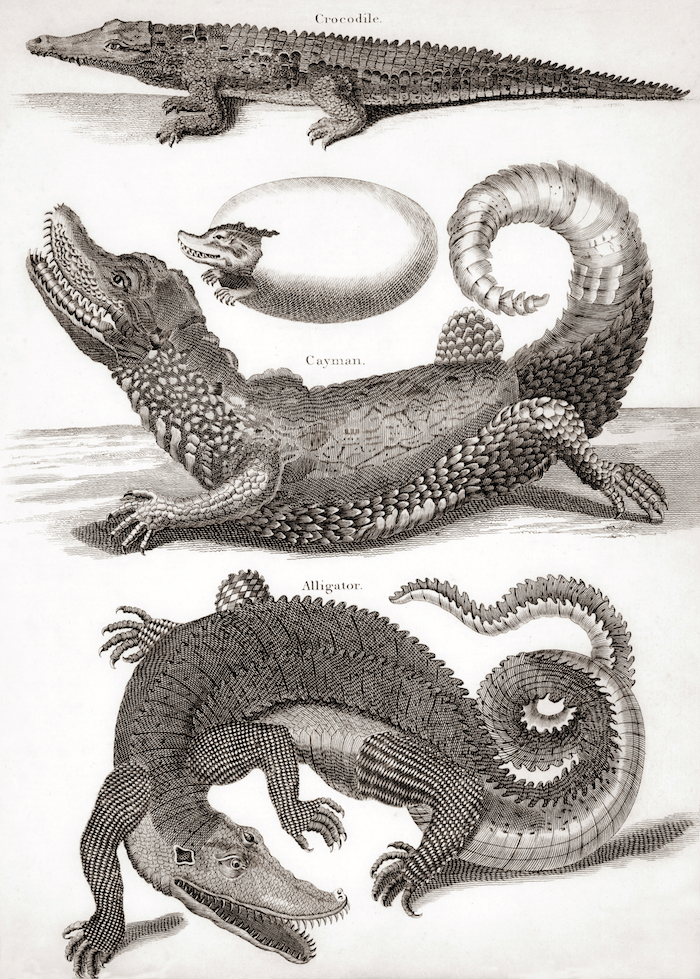

While stationed in New Orleans to repel invading French and Spanish forces, J.F.D. Smyth experienced this firsthand. ‘In the river, and in the creeks, rivulets and water-courses’, he wrote in his journal, ‘are large dangerous animals named alligators, from ten to eighteen feet and upwards in length.’ He continued:

they are a species of the crocodile, and equally, if not more dangerous than those of the river Nile in Egypt; these also devouring men, oxen, or whatever else they can get within their horrid jaws, in that crafty subtle manner.

Because of this near and present danger Smyth and his men spent much of their time in the Louisiana swamps searching for high ground. They refused to sleep in open bateaux, the shallow, flat-bottomed boats used to traverse rivers, instead opting to camp on shore ‘near to a large fire, which always prevents the approach of any beasts of prey’. During the Siege of Charleston in 1780, the Hessian soldier Carl Bauer was startled when he ‘saw many tracks of alligators and crocodiles in the creeks’, while his comrade, Johann Ewald, came face-to-face with ‘alligators from ten to twelve feet long’.

‘Crocodilia: crocodile, caiman and alligator’, 18th-century engraving. Bridgeman Images.

‘Crocodilia: crocodile, caiman and alligator’, 18th-century engraving. Bridgeman Images.

Alligators were indeed rife in the southern states. Travelling in the same area during the years of the war, the American naturalist William Bartram recorded his encounters with Florida’s crocodiles in Bartram’s Travels, his account of his explorations in the Southern Colonies between 1773 and 1777. Bartram described how crocodiles were his constant, and terrifying, companions. They glided next to his vessel, or ‘roared’ at him from their ‘nests’ on the shore. Bartram watched with curious horror, noting there ‘are to be seen incredible numbers of crocodiles, some of which are of an enormous size, and view the passenger with incredible impudence and avidity’. ‘So abundant’ were they, Bartram reflected, that ‘if permitted by them, I could walk over any part of the bason and the river upon their heads, which slowly float and turn about like knotty chunks or logs of wood’. On one occasion Bartram witnessed the ‘horrid combat’ between two crocodiles: ‘The earth trembles with thunder … the boiling surface of the lake marks their rapid course, and a terrific conflict commences.’ On another, he recalled waking to find a crocodile ‘dashing [his] canoe against the roots of a tree’.

Though Smyth, Bartram and Bauer referred to the beasts as crocodiles, they were actually encountering the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) – the two terms were used interchangeably in 18th-century parlance. The animal could (and can) weigh as much as 450 kilogrammes and has a bite three times more powerful than a lion’s. While we cannot be sure how many soldiers were lost to alligators, their recollections convey horror at the constant possibility. The ‘roar and menaces’ of these ‘monsters’ terrified British and Hessian troops. In a final, furious finish to Bartram’s alligator-infested southern sojourn, he awoke one night to find his companions ‘up in arms, and furiously engaged with a large alligator but a few yards from me’. The creature ‘roared and bellowed hideously’ as Bartram’s men prodded it with spears, firebrands, and anything else they could get their hands on. So great was ‘his strength and fury’ that it took Bartram’s men hours to kill their 12-foot foe, a ‘voracious, formidable animal’

The Mosquito Coast

Nightly fires may have deterred alligators, but they could do little against a far more persistent problem. The American swamplands were home to mosquitoes, the size of which dwarfed any the soldiers had encountered in their homelands. No matter where they marched, camped, and fought, soldiers constantly remarked upon the swarms of mosquitoes during the spring and summer months. One Hessian soldier called their sting ‘a small torture’, while another described the insect as ‘a natural scourge’, in which America ‘surpasses all other countries in the whole world’. Many troops smoked their tents at night, while others covered their bodies with gloves and handkerchiefs to defend themselves from ‘their most offensive stinging’. ‘Where [mosquitoes] bite’, one Hessian exclaimed, ‘the flesh immediately swells up, burns, and causes a great pain so that a person does not know what to do.’

The threat posed by mosquitoes was not confined to surface irritations. Malaria and yellow fever were among the most common causes of death in Revolutionary America. For every British or Hessian soldier who died in combat, eight died of disease. Unlike the Americans, British and German troops had little or no prior exposure or experience with malaria or yellow fever, and were especially vulnerable to the diseases during the stifling summer months. To make matters worse, colonists had spent much of the previous century cultivating a perfect environment for mosquitoes in the flooded-out rice fields of the Southern colonies, especially South Carolina. It would be mosquitoes more, perhaps, than anything else that sealed the defeat of Cornwallis’ troops against a combined American and French force, led by George Washington, at the Siege of Yorktown in Virginia in 1781. Malaria was said to have reduced the number of Cornwallis’ forces by as much as 65 per cent.

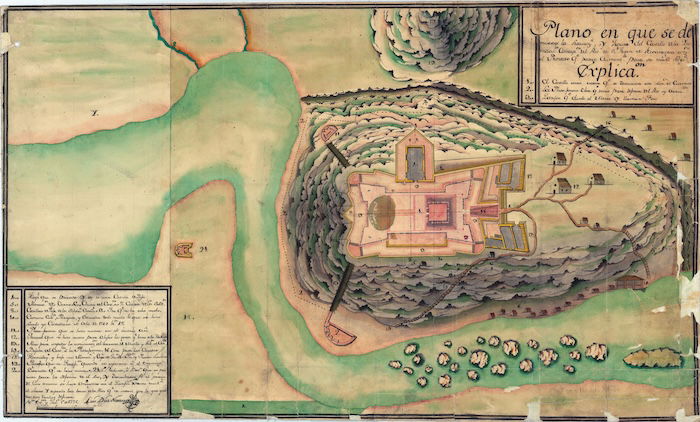

Plan of the Spanish Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, c.1750. Archivo General de Indias. Public Domain.

Plan of the Spanish Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, c.1750. Archivo General de Indias. Public Domain.

In 1780 Horatio Nelson was a 22-year-old captain in the Royal Navy. In March that year he and Captain John Polson led the San Juan Expedition, an attempt to capture the Spanish Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, which had been completed in 1675 on the San Juan river downstream from Lake Nicaragua. France and Spain’s official alliance with the Americans in 1779 forced the British forces not only to defend their holdings in the torrid, swampy, alligator-infested environs of Florida, but also to invade – and hopefully gain control of – other hostile regions, including Central America’s ‘Mosquito Coast’.

The young captain’s orders were clear: control the mouth of the San Juan river and supply transport ships to forces who would penetrate Nicaragua and Honduras and capture the inland Spanish fortress. Command of Central America would mean control over military and trade routes across the Pacific Ocean. In late March, Nelson and his troops found the San Juan river with little difficulty. Yet as he and his roughly 50 troops paddled their boats and canoes into the rainforest, they found themselves in a biome unlike any they had experienced before. As a soldier who accompanied Nelson recalled, ominous trees loomed over them ‘like Gothic columns with evergreen arches, covering cool, dark vistas’. It was difficult to see a distance of more than a few yards. Manatees swam alongside their crafts, which alarmed many of Nelson’s troops, who thought they had seen crocodiles (which were also present). Another soldier was astonished to see ‘ugly iguanas looking curiously down upon us from the projecting limbs of trees’.

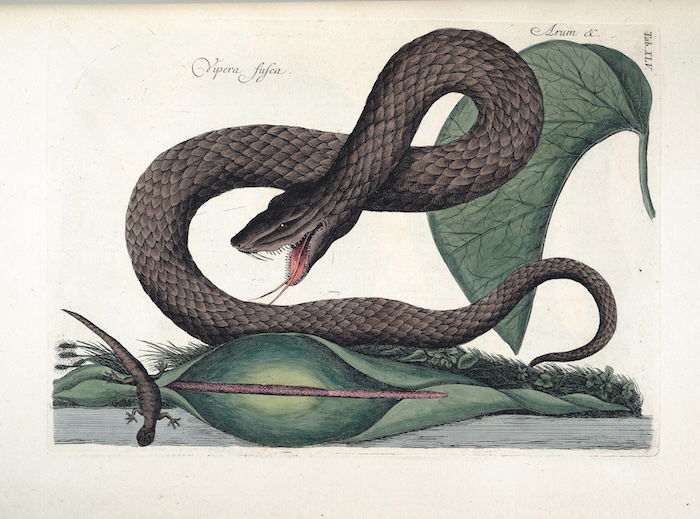

Nelson wrote that he struggled to keep his men focused in what one of his physicians called ‘these horrid woods’, ‘so thick as to intercept the rays of the sun’. They retreated to the shore for camp where, one afternoon, Nelson awoke to find a large iguana (a ‘monitory lizard’, in his words) on his lap. As he struggled to push the creature from him, he saw that a snake had coiled itself at his feet. Others were less lucky. In early April, an unfortunate British soldier walked into a snake that was hanging from a branch. It bit him in the eye. ‘He felt such intense pain’, a physician noted, ‘that he was unable to proceed’. Though the man’s comrades attempted to suck the venom from him, the man died ‘with all the symptoms of putrefaction’: bloated, skin coloured yellow, his eye dissolved.

On 13 April, Nelson’s troops arrived at the fortress and began a siege. Shortly after they made camp, a jaguar attacked one of Nelson’s peripheral units. According to Captain Richard Bulkeley, the animal ‘plunged headlong among the men, missed the one he was pursuing and caught another by the neck, tore his clothes and hurt his face’. The Native Americans, who the British had recruited as allies in an attempt to negate the dangers of the environment, ‘made a great howling … and frightened the [jaguar] away’. As the men nursed their wounds, Bulkeley remarked that the jaguar ‘must have been much pressed with hunger, not being first attacked, to pursue a man where there were fires and a multitude of people’.

A snake, from Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, 1729-49. National Gallery of Art Washington. Public Domain.

A snake, from Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, 1729-49. National Gallery of Art Washington. Public Domain.

The jaguar encounter was followed by another incident. A group of thirsty soldiers drank from a pool of what appeared to be clean water. Within hours the men’s mouths and throats had swollen to the point that they found it difficult to breathe and they had begun to vomit. A poisonous manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) had hung above the pool and dropped its fruit into the water. The English botanist Philip Miller had warned of the manchineel’s toxicity in his popular Gardener’s Dictionary (1731-68): the tree’s sap ‘raise[d] Blisters on the Skin, and burn[ed] Holes in Linen’, while consuming the fruit or its by-products would ‘corrode the Mouth and Throat’, often leading to death. Luckily for Nelson’s soldiers, the water had diluted the poison to such an extent that none died.

Though the British forces were able to capture the fortress on 29 April they had to retreat immediately, and the Spanish regained control in January 1781. Nelson did not see his troops take the fortress: seriously ill, he had returned downriver the day before the Spanish surrender. The arrival of tropical rains in late April brought with it the arrival of malaria and dysentery. Nelson was treated for malaria, along with ‘bilious vomitings, nervous headaches, visceral obstructions and many other bodily infirmities’. He later wrote that the Mosquito Coast’s environment had ‘destroyed my health and crushed my spirit’. He received permission to return to England for a ‘speedy recovery’. ‘Home and dear friends will restore me’, he wrote: ‘I shall recover and my dream of glory be fulfilled. Nelson will yet be an Admiral.’

Happy land

But while British troops suffered in the hostile environment of the New World, the American rebels embraced a narrative of natural superiority. In the decades preceding the war, the British media had routinely derided America as an inferior land, ‘of which’, in the estimation of the physician and botanist John Mitchell writing in 1767:

one half is constantly frozen, and does not produce so much as a tree, or a bush, or a blade of grass; two thirds are uninhabitable for the same reason; and three-fourths of these territories will not produce the necessaries of life.

America’s environment was not the problem, the rebels countered: Europeans were. As a contributor to Boston’s Independent Ledger wrote on 5 July 1779:

America blossoms as the expanding rose, and rises like the towering cedar; every morning sun views her increased fame, and each new day extends her domain, and adds new glories to her crown.

Natural allegories were common in this period, as the author urged his fellow Americans to ‘look eastward, and westward, northward and southward – the stores of nature, and the blessings of the universe, are ready to pour into your happy land’.

British and Hessian combatants, meanwhile, tried to make sense of their suffering. Many blamed the defeat on the environment. Reflecting upon his years as a chief surgeon in Revolutionary America, the Hessian doctor Johann David Schoepff wondered whether those ‘westerly gales, fogs, and mighty seas’ had been ‘cast in the way of Europeans by a beneficent Providence as so many warnings to keep off’. And he was not alone. Sulking about Brighton’s beaches in 1781, Thomas Hughes grappled with similar questions. He admitted to regularly reflecting upon ‘nature in her most tremendous appearances’ during his solitary strolls. Those soldiers who did survive the wilderness did not forget it.

Vaughn Scribner is Associate Professor of British American History at the University of Central Arkansas. His most recent book is Under Alien Skies: Environment, Suffering, and the Defeat of the British Military in Revolutionary America (The University of North Carolina Press, 2024).

.png)