“If you’re explaining, you’re losing.” This line is usually attributed to Ronald Reagan. Whoever said it definitely had a point, and not just about politics. If you’re trying to explain to people, be they voters or bond investors, that you aren’t really as bad or untrustworthy as you seem, you’re already in deep trouble.

So when I saw Scott Bessent, the treasury secretary, declaring Sunday that “The United States of America is never going to default, that is never going to happen,” my reaction was, “Uh-oh.”

And it’s not just me. For generations investors have treated U.S. government debt as the ultimate safe asset. Whenever disaster strikes — even if it’s disaster largely made in America, like the 2008 subprime crisis — bond buyers pile into U.S. Treasuries, because America is a serious country, and the idea that we would fail to honor our debts was unthinkable.

But are we still that country? Markets seem to have doubts.

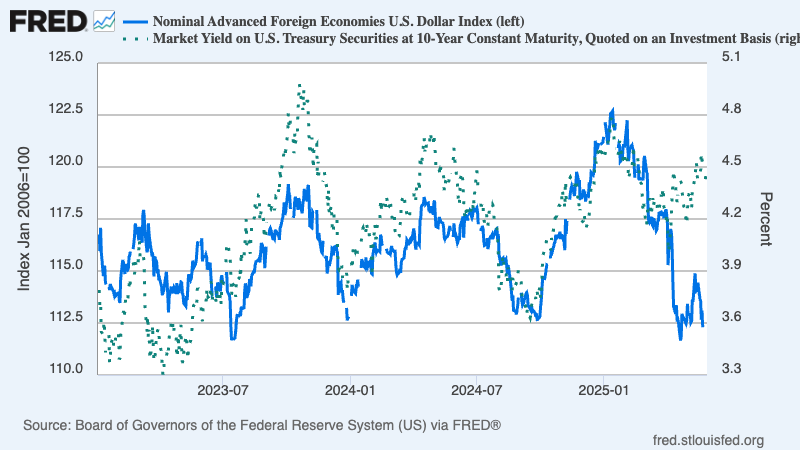

Yesterday the Financial Times had a neat chart showing that there used to be a clear relationship between U.S. interest rates and the international value of the dollar. Actually, the chart was a bit too neat: When I set out to reproduce it, I found that the FT chose a time period during which the relationship looked especially clear. Still, it used to be true that when U.S. interest rates rose, so did the dollar, because higher yields pulled in foreign capital. But since Donald Trump returned to power, that relationship has broken down. Instead, we’ve seen a combination of rising interest rates and a falling dollar:

As many have noted, what we’ve been seeing in recent months, with interest rates and the dollar moving in opposite directions, doesn’t look like what we normally see in the United States, or for that matter advanced nations in general. Instead, it’s the kind of thing one sees in emerging markets, where big market moves often reflect crises of confidence: International investors lose faith, pulling their money out, and capital flight causes both a falling currency and rising interest rates.

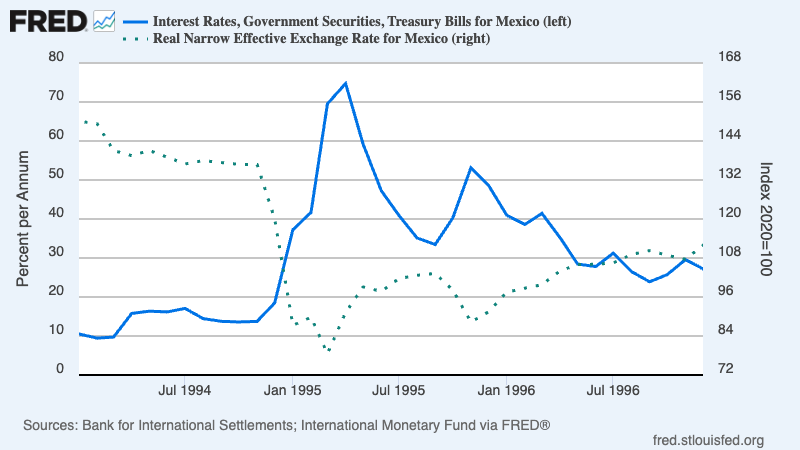

Here, for example, is what Mexico looked like during the “tequila crisis” of 1994-5, which involved both soaring interest rates and a plunging peso:

Why are markets beginning to treat America as unreliable? It’s not just the debt numbers. Yes, we have large debts, but we’re an immensely wealthy country that, among other things, has lower average taxes than most of our peers. So we certainly have the resources to honor our debts.

But do we have the political will? Maybe even more important, do we have the political seriousness?

Like many economists, I’ve spent a lot of time analyzing the substance of Trump’s tariffs — how much they are likely to raise prices and reduce trade volumes. I’ve also written about the impacts of policy uncertainty, about how hard it is for businesses to make plans when they have little idea what tariff rates will be even a few months from now, let alone over the next few years.

But I wonder whether we’ve spent enough time looking at the policy process — how decisions get made in Trump’s America. Consider: On April 2, “Liberation Day,” Trump announced extremely high tariffs on many countries, the biggest tariff hike in U.S. history. The tariff rates — which differed hugely from country to country — were determined by a formula universally panned as stupid and ridiculous. And this tariff announcement was made with so little planning and forethought that it included taxes on imports from remote islands inhabited only by penguins.

Then, a week later, these tariffs were replaced by a completely different set of tariffs. How did that happen? Two of Trump’s cabinet members were able to beard him in the Oval Office while Peter Navarro, responsible for the original tariffs, was in another meeting.

Does this sound like policymaking in a serious country?

Then there’s the budget bill making its way through Congress. It’s a terrible thing, imposing savage cuts on social programs (and decimating U.S. science) while giving such big tax cuts to the wealthy that it will explode the deficit. But content aside, notice that this hugely important piece of legislation is being rushed through with essentially no hearings or analysis.

And when outsiders, including the Congressional Budget Office and a variety of think tanks — conservative and centrist as well as progressive — have put out the analyses the bill’s sponsors won’t, pointing out the likely effects on debt, health coverage, and so on, the G.O.P. response has basically been to accuse all of the independent analysts of being part of a globalist conspiracy.

Wait, it gets worse. The name of the legislation — not its nickname, its official title — is the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, because that’s what Trump has been calling it. Are we a mature republic with a normal head of state, or are we being ruled by Kim Jong Un in orange makeup?

Why, next thing you’ll be telling me that key policy decisions, leading to layoffs of hundreds of thousands of federal workers and many deaths around the world, have been made by a presidential crony whose erratic behavior may have reflected massive consumption of ketamine, Ecstasy and psychedelic mushrooms. Oh, wait.

Imagine yourself as a foreigner considering investing in the United States. You may well know that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act contains a “revenge” provision that would allow the U.S. government to impose extra taxes on foreign investors whose home countries have policies America doesn’t like. You probably know that one of Trump’s advisers has suggested the forced conversion of short-term debt into century bonds. Once upon a time everyone would have dismissed these things as stuff that couldn’t happen in America. Now? Who knows?

In a way, the amazing thing is that we haven’t seen even more capital flight. Presumably investors still can’t believe that America has changed so much from the responsible, reliable nation it seemed to be just a few months ago.

But I think they’re headed for a rude awakening.

MUSICAL CODA

.png)