OpenAI and Stripe announced what they call the Agentic Commerce Protocol (ACP for short). The idea behind it is to enable AI agents to make purchases autonomously.

It’s not hard to guess that the response from smartass merchants would come almost immediately.

As much fun as we can make of those attempts to make a quick buck, the whole situation is way more interesting if we look beyond the technical and security aspects.

Shallow Perception of Autonomous AI Agents

What drew popular interest to the Stripe & OpenAI announcement was an intended outcome and its edge cases. “The AI agent will now be able to make purchases on our behalf.”

- What if it makes a bad purchase?

- How would it react to black hat players trying to trick it?

- What guardrails will we have when we deploy it?

All these questions are intriguing, but I think we can generalize them to a game of cat and mouse. Rogue players will prey on models’ deficiencies (either design flaws or naive implementations) while AI companies will patch the issues. Inevitably, the good folks will be playing the catch-up game here.

I’m not overly optimistic about the accumulated outcome of those games. So far, we haven’t yet seen a model whose guardrails haven’t been overcome in days (or hours).

However, unless one is a black hat hacker or plans to release their credit-card-wielding AI bots out in the wild soon, these concerns are only mildly interesting. That is, unless we look at it from an organizational culture point of view.

“Autonomous” Is the Clue in Autonomous AI Agents

When we see the phrase “Autonomous AI Agent,” we tend to focus on the AI part or the agent part. But the actual culprit is autonomy.

Autonomy in the context of organizational culture is a theme in my writing and teaching. I go as far as to argue that distributing autonomy throughout all organizational levels is a crucial management transformation of the 21st century.

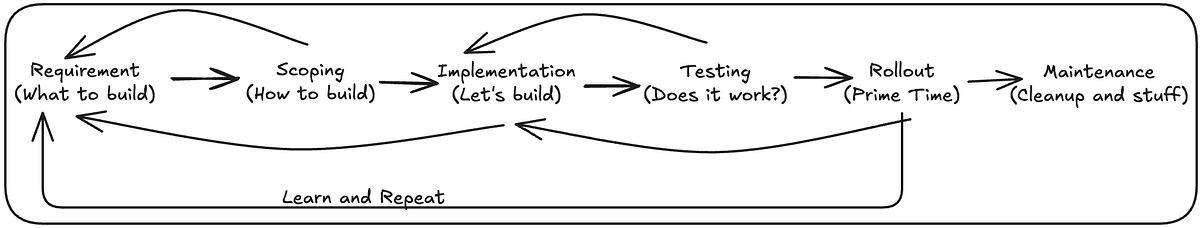

And yet we can’t consider autonomy as a standalone concept. I often refer to a model of codependencies that we need to introduce to increase autonomy levels in an organization.

The least we need to have in place before we introduce autonomy are:

- Transparency. We can’t let people make decisions without relevant data to inform them, or decisions will be plain wrong.

- Technical excellence. Independence in acting requires the capabilities to perform these acts competently.

- Alignment. Unless we align everyone’s efforts, more autonomy only means more pull toward opposing directions.

- Explicit boundaries. We need to understand the limits within which we can act autonomously. Otherwise, we’d be both overwhelmed with possibilities and petrified by potential consequences.

- Care. Without intrinsic, genuine care about the outcomes of our decisions and actions, it’s just flailing around (and without purpose, let me add).

Remove either, and autonomy won’t deliver the outcomes you expect. Interestingly, when we consider autonomy from the vantage point of AI agents rather than organizational culture, the view is not that different.

Limitations of AI Agents

We can look at how autonomous agents would fare against our list of autonomy prerequisites.

Transparency

Transparency is a concept external to an agent, be it a team member or an AI bot. The question is about how much transparency the system around the agent can provide. In the case of AI, one part is available data, and the other part is context engineering. The latter is crucial for an AI agent to understand how to prioritize its actions.

With some prompt-engineering-fu, taking care of this part shouldn’t be much of a problem.

Technical Excellence

We overwhelmingly focus on AI’s technical excellence. The discourse is about AI capabilities, and we invest effort into improving the reliability of technical solutions. While we shouldn’t expect hallucinations and weird errors to go away entirely, we don’t strive for perfection. In the vast majority of applications, good enough is, well, enough.

Alignment

Alignment is where things become tricky. With AI, it falls to context engineering. In theory, we give an AI agent enough context of what we want and what we value, and it acts accordingly. If only.

The problem with alignment is that it relies on abstract concepts and a lot of implicit and/or tacit knowledge. When we say we want company revenues to grow twice, we implicitly understand that we don’t plan to break the law to get there.

That is, unless you’re Volkswagen. Or Wells Fargo. Or… Anyway, you get the point. We play within a broad body of knowledge of social norms, laws, and rules. No boss routinely adds “And, oh by the way, don’t break a law while you’re on it!” when they assign a task to their subordinates.

AI agents would need all those details spoon-fed to them as the context. That’s an impossible task by itself. We simply don’t consciously realize all the norms we follow. Thus, we can’t code them.

And even if we could, AI will still fail the alignment test. The models in their current state, by design, don’t have a world model. They can’t.

Alignment, in turn, is all about having a world model and a lens through which we filter it. It’s all about determining whether new situations, opportunities, and options fit the abstract desired outcome.

Thus, that’s where AI models, as they currently stand, will consistently fall short.

Explicit Boundaries

Explicit boundaries are all about AI guardrails. It will be a never-ending game of cat and mouse between people deploying their autonomous AI agents and villains trying to break bots’ safety measures and trick them into doing something stupid.

It will be both about overcoming guardrails and exploiting imprecisions in the context given to the agents. There won’t be a shortage of scam stories, but that part is at least manageable for AI vendors.

Care

If there’s an autonomy prerequisite that AI agents are truly ill-suited to, it’s care.

AI doesn’t have a concept of what care, agency, accountability, or responsibility are. Literally, it couldn’t care less whether an outcome of its actions is advantageous or not, helpful or harmful, expected or random.

If I act carelessly at work, I won’t have that job much longer. AI? Nah. Whatever. Even the famous story about the Anthropic model blackmailing an engineer to avoid being turned off is not an actual signal of the model caring for itself. These are just echoes of what people would do if they were to be “turned off”.

AI Autonomy Deficit

We can make an AI agent act autonomously. By the same token, we can tell people in an organization to do whatever the hell they want. However, if we do that in isolation, we shouldn’t expect any sensible outcome. In neither of the cases.

If we consider how far we can extend autonomy to an AI agent from a sociotechnical perspective, we don’t look at an overly rosy picture.

There are fundamental limitations in how far we can ensure an AI agent’s alignment. And we can’t make them care. As a result, we can’t expect them to act reasonably on our behalf in a broad context.

It absolutely doesn’t limit specific and narrow applications where autonomy will be limited by design. Ideally, those limitations will not be internal AI-agent guardrails but externally controlled constraints.

Think of handing an AI agent your credit card to buy office supplies, but setting a very modest limit on the card, so that the model doesn’t go rogue and buy a new printer instead of a toner cartridge.

It almost feels like handing our kids pocket money. It’s small enough that if they spend it in, well, not necessarily the wisest way, it’s still OK.

Pocket-money-level commercial AI agents don’t really sound like the revolution we’ve been promised.

Trust as Proxy Measure of Autonomy

We can consider the combination of transparency, technical excellence, alignment, explicit boundaries, and care as prerequisites for autonomy.

They are, however, equally indispensable elements of trust. We could then consider trust as our measuring stick. The more we trust any given solution, the more autonomously we’ll allow it to act.

I don’t expect people to trust commercial AI agents to great extent any time soon. It’s not because an AI agent buying groceries is an intrinsically bad idea, especially for those of us who don’t fancy that part of our lives.

It’s because we don’t necessarily trust such solutions. Issues with alignment and care explain both why this is the case and why those problems won’t go away anytime soon.

Meanwhile, do expect some hilarious stories about AI agents being tricked into doing patently stupid things, and some people losing significant money over that.

Thank you for reading. I appreciate if you sign-up for getting new articles to your email.

I also publish on Pre-Pre-Seed substack, where I focus more narrowly on anything related to early-stage product development.

.png)