A historian’s perspective on how to deal with the Nobel frenzy

I generally try to stay away from the Economics Nobel frenzy, if only because the hyper-personalization of scientific achievements it entails it at odds with how we historians understand credit dynamics in science. Economics research has become increasingly collective, drawing on expertise in theory, data collection, empirical techniques, sometimes philosophy, law or psychology. There’s a tradeoff here, of course—one I’ve witnessed in the archives of the John Bates Clark Medal, awarded annually to an economist under 40 working in the US. These prizes generate expectations, divisions, and disappointments within the discipline, but they buy something valuable: prestige and visibility beyond it. They signal to the broader public that this work matters.

But I was one of the researchers asked to comment, almost live, on this year’s award on the French radio today, and as it happens, some good collective work by historians of economics on the 20th growth economics has been published recently. So here’s a post with a few references and thoughts. I won’t describe the laureates’ contributions because (1) the Nobel committee does that very well, (2) dozens of posts doing exactly that will appear in the next hours (see for instance Brian Albrecht at Econforces, the write-up of Mokyr’s work by Anton Howes, himself a great historian of technology, and watch out for Kevin Bryan’s always excellent summary on his blog A fine Theorem) and (3), the 2025 laureates happen to be excellent writers and vulgarizers, so just go read their books.

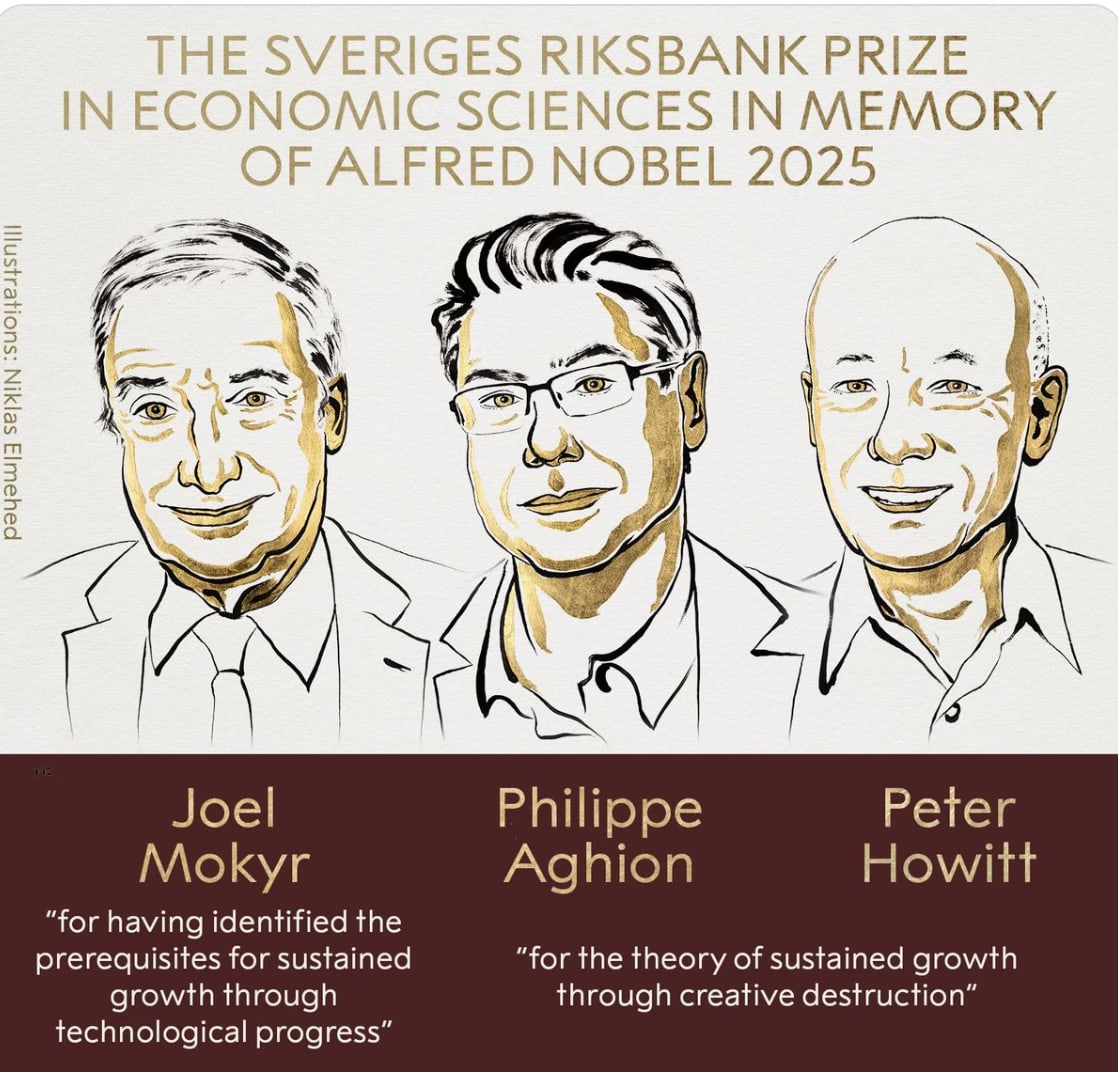

Israeli-American economic historian Joël Mokyr received half of the prize, while French Philippe Aghion and Canadian Peter Howitt shared the other half. As has become common in the past decades, the prize is framed as a award for methods – not for results, not for policy recommendations, but primarily for methods.

Of course, the laureates do reach substantive conclusions. Mokyr demonstrates that sustained growth in the long run emerged from the combining two types of knowledge during the European renaissance: propositional knowledge (scientific knowledge on why things work) and prescriptive knowledge (practical knowledge on the how to make them work). This combination requires particular institutional and historical conditions, including political fragmentation, the Enlightenment, the development of a market of ideas in Europe whereby intellectual could challenge orthodoxy, and especially in Britain, a culture of progress. Building on Joseph Schumpeter, Aghion and Howitt argue that growth springs from creative destruction, a process whereby entrepreneurs try to escape competition by innovating to gain an edge over rivals.

But these conclusions haven’t gone unchallenged. Aghion and Howitt famously sparred with Stanford’s Charles Jones over the importance of R&D and population size and scale effects (as summarize by Acemoglu here and, see also this survey). Mokyr’s work provoked a controversy with Robert Allen over the causes of the British Industrial Revolution (see Crafts’s review of the controversy): was industrialization driven, as Mokyr argues, by cultural and scientific change—the circulation of ideas, Britain’s culture of progress and practical application? Or was it, as Allen contends, about higher wages, cheaper energy, and technical education? Behind these debates lies a deeper question: what fundamentally drives growth? Education (and which type)? Innovation? Learning by doing? Fertility? Geography? Institutions?

Economists disagree even more over these theories’ policy implications. What, then, constitute good competition policy? God industrial policy? Who should fund innovation and how? What level of intellectual property protection is appropriate? Can we pursue both decoupling and green growth simultaneously?

Ironically, shaping public policies is precisely why the Economics Nobel, or rather, the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel” was created. Avner Offer, Gabriel Soderberg and Phil Mirowski’s archival research reveal that the prize was a “coup” engineered in 1968 by Swedish central bank governor Per Åsbrink. After a decade of failed attempts to gain independence from Tage Erlander’s Social Democratic government—particularly the power to set interest rates autonomously—Åsbrink found another path. He would use central bank funds to establish an economics prize celebrating the institution’s tricentenary.

Advised by Assar Lindbeck, who would dominate the economics Nobel committee for the next 25 years, Åsbrink pressured the Nobel family patriarch into accepting the plan. The Nobel Foundation, then controlled by industrialists, approved. The announcement followed quickly. Like other science prizes, it would be administered by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. “Economic science today is so developed and established as a scientific discipline,” Åsbrink declared, leaving no room for doubt. He believed rewarding this “science” would shift policy debates toward the monetary orthodoxy he favored.

The prize was, as Offer and Söderberg call it, a “vanity project”—explicitly designed to transfer sixty years of accumulated scientific prestige from physics, chemistry, and biology to economics. It succeeded spectacularly. Yet the authors find no systematic ideological pattern in the laureates who followed. The prize has simply become the public marker of what constitutes good economic science.

What these three economists got the 2025 Nobel for, then, is the new toolboxes they developed to study sustained growth. Mainstream economists may dispute their specific conclusions -how much innovation drives growth, what drives innovation itself- but they recognize that the methods have led to fruitful debates and contributions. And as usual, the Nobel committee has managed to walk a thin line between alternative approaches, bringing some together.

On one side: Aghion and Howitt’s mathematical model. They formalized Schumpeter’s creative destruction by building in microfoundations—showing how entrepreneurs’ choices generate and sustain innovation. It was a breakthrough compared to Solow’s seminal model (with exogeneous technical progress). Historians and writers have recently examined this shift, though with a greater focus on the work by Bob Lucas and Paul Romer, both earlier Nobel Prizes. Goulven Rubin, who has edited a recent special issue on the history of endogenous growth theory, outlines a puzzle at the heart of this story. Though several contributors have now won Nobels for their 1990s contributions, there was already a wave of endogenous growth models in the 1960s (think Arrow on learning-by-doing, Uzawa, Sheshinski, Shell and others). Why did the first wave falter while the second took off?

Perhaps because of these microfoundations. Perhaps also because their model was crafted in a way that allowed them to confront it with the new large firm-level datasets that were built in the decades. After the 1990s, Aghion has offered a range of empirical studies of the role of innovation in growth and the consequences of various types of policies, with a host of coauthors (see his recent work on how to subsidies car batteriesfor instance).

While the 1992 article for which Aghion and Howitt received the prize is representative of Aghion lifelong approach, for Howitt it represented just one step in a more eclectic intellectual journey. This comes through in another recent history of economics special issue, edited by Muriel Dal Pont and Hans-Michael Trautwein to celebrate Howitt receiving an honorary degree from Université Côte d’Azur. Tellingly, the special issue focuses neither on innovation nor on endogenous growth, but on the history of coordination failures in economics.

In their introduction, Dal Pont and Trautwein trace Howitt’s intellectual development, from the foundational influence of Keynes — see also the papers by David Laidler and Sylvie Rivot on how Howitt’s Keynesian commitments — through his contributions to disequilibrium theory à la Clower and Leijonhufvud, his joint work with Aghion, and most recently, his turn towards agent-based modeling to explain inflation. They see Howitt’s work as unifed by a single question “understand how market mechanisms can fail,” which requires addressing coordination issues in the short run (as macroeconomists usually do) and in the long-run. “In particular,” they write, “he sees adjustments to technological change not as a mere self-limiting transition to a new steady state but as a permanent condition of economic life in a progressing society, that is, a long-run phenomenon.” Howitt himself explains his approach in a contribution to the volume.

Even accounting for Aghion and Howitt’s diverging methodological paths, Mokyr is the outlier. He has few publications in top 5 journals. His methods are unambiguously historical. Now, rewarding economic historians is definitely a trend in the latest Nobel rounds (Acemoglu-Johnson-Robinson, Goldin, Bernanke), which is not quite reflected in the profession at large (for instance on the job market). But Mokyr’s approach stands as the most historical. He uses comparative analysis, waves together qualitative and quantitative evidence including correspondence, technical books, renaissance archives. He crafts narratives, he considers historical paths as unique.

Tanguy Le Fur’s work on the history of very long-run perspectives on growth among economic historians captures this tension. Having studied Oded Galor’s contributions, he’s now examining Mokyr’s. In the conclusion of his Galor paper, he notes that “the dichotomy between growth theory and economic history has thus been tackled by practitioners of both fields.” Yet here’s the irony: the Nobel committee has yoked together researchers working on the same question from different methodological perspectives, barely aware of each other’s work

How to approach the coming week of commentary, then? Expect rounds of applause and criticism, focused on different questions.

First, method. Are the laureates’ approaches appropriate? Nobel awards reflect methodological consensus within mainstream economics, so epistemological controversy will be muted—though whether Mokyr, or even Howitt, count as mainstream is debatable. Still, innovation and growth are central to heterodox traditions too, particularly evolutionary economics (see for instance the work by Richard Nelson, Sidney Winter and Giovanni Dosi, as well as Paul David’s economics of science approach to innovation. I mention these because they somehow rely on Schumpeterian framework, but there are so many others).

Second, conclusions: Does innovation drive sustained growth, or do other factors matter more?

Third, policy. If the laureates are right, what follows? What should industrial policy look like? Competition policy? Who funds innovation? For what? Given the prize’s history, media and publics will press laureates and commentators to weigh in on far broader policy questions—France’s Zucman tax, trade policy, Fed independence, debt levels, budget discipline. The Nobels’ authority will be invoked to legitimize political positions, often on topics the laureates never touched or framed differently.

Finally, the focus on growth and innovation itself including Aghion’s recent work with coauthors on innovation-driven energy transition—could itself become contentious. Some economists argue there’s too little attention to long-term drivers of European growth and innovation support. Others argue there’s too much focus on growth altogether—the green growth versus degrowth debate. (for some historical perspective on the dominance of the growth paradigm in economics, see Schmelzer’s history of growth theory, and his edited volume with Iris Borowy. There’s also a book by Christopher Jones just out this month, as well as this cool paper on mainstream vs ecological economists by Quentin Couix),

It is important that we, as researchers, medias and citizens, disentangle these different layers of conversations.

.png)