Like a lot of firsts, the first powered flight wasn’t all that impressive.

After years of building bicycles, then gliders, and finally powered aircraft prototypes, the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville, took their invention to the beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina for testing. They chose Kitty Hawk because they could use the steady winds coming off of the ocean — and because the sand would provide a soft landing in the very likely event of a crash.

After a botched takeoff on December 14, 1903, delayed their efforts for a few days, Orville managed to use strong winds to get his Flyer off the ground. The first powered flight, on December 17, traveled about 120 feet. It lasted 12 seconds, probably about as long as it took you to read this paragraph.

The brothers made a few more attempts that day, managing a few more flights of less than 20 seconds. The day’s great achievement was a journey of 852 feet. It lasted 59 seconds. A little bit after this fourth flight, the winds picked up and caught the aircraft, flipping and badly damaging it. That unintentional flight would be the Wright Flyer’s last journey.

A flight of 0.16 miles lasting less than a minute was proof of concept, but not much more. But at least the Wright brothers could stake a firm claim to being the first, right?

Well, things didn’t seem that clear-cut back in 1903. There had been no outside observers at Kitty Hawk that day. The brothers themselves didn’t make much of a fuss about their achievement; they refused to speak to the North Carolina press because they wanted the story to first be published in their hometown of Dayton, Ohio. The story in the Virginia Pilot was very inaccurate:

Flying Machine Soars Three Miles in Teeth of High Wind Over Sand Hills and Waves On Carolina Coast

No Balloon Attached To Aid It

Three Years of Hard, Secret Work By Two Ohio Brothers Crowned With Success

Accomplished What Langley Failed At

With Man As Passenger Huge Machine Flies Like Bird Under Perfect Control

The Wrights’ flight was lightly covered by the press; only six newspapers ran the initial story about their exploits at Kitty Hawk. The Wrights tried to correct the record with a statement to the press in January, but it was all quite confusing. Had they done something momentous?

Like many technological firsts, the reality becomes more complicated the more questions you ask. What, exactly, constitutes a flight? What does it mean for a flight to be powered? What does it mean for a flight to be controlled?

The Wright brothers weren’t the only people to claim that they had made the first flight. Around the turn of the 20th century, independent inventors all over the world understood that powered aviation was right around the corner and were racing one another to be first. Several of them had at least semi-credible claims to have beaten the Wright brothers into the air.

A German immigrant in Connecticut named Gustave Whithead had, like the Wrights, been plugging away in relative obscurity at the problem of powered flight. He built over 50 planes and gliders, and, according to him, beat the Wright brothers into the sky by two years. He claimed in Scientific American to have built a “novel flying machine” with a 20-horsepower engine in 1901. On August 18, 1901, the Bridgeport Herald published an account of what he claimed was his first flight. He’s quoted in the article as saying

I never felt such a strange sensation as when the machine first left the ground and started on her flight. I heard nothing but the rumbling of the engine and the flapping of the big wings. I don’t think I saw anything during the first two minutes of the flight, for I was so excited with the sensations I experienced. When the ship had reached a height of about forty or fifty feet I began to wonder how much higher it would go. But just about that time I observed that she was sailing along easily and not raising any higher. I felt easier, for I still had a felling of doubt about what was waiting for me further on I began now to feel that I was safe and all that it would be necessary for me to do to keep from falling was to keep my head and not make any mistakes with the machinery. I never felt such a spirit of freedom as I did during the ten minutes that I was soaring up above my fellow beings in a thing that my own brain had evolved. It was a sweet experience. It made me feel that I was far ahead of my brothers for I could fly like a bird, and they must still walk.

Whitehead wrote in to American Inventor magazine the next year with similar claims. The editors were skeptical:

Newspaper readers will remember several accounts of Mr. Whitehead’s performances last summer. Probably most people put them down as fakes, but it seems as though the long-sought answer to the most difficult problem Nature ever put to man is gradually coming in sight. The Editor and the readers of these columns await with interest the promised photographs of the machine in the air. The similarity of this machine to Langley’s experimental flying machine is well shown in the accompanying illustration, reprinted from a previous issue. Mr. Langley, it will be remembered, was the first to demonstrate the possibility of mechanical flight.

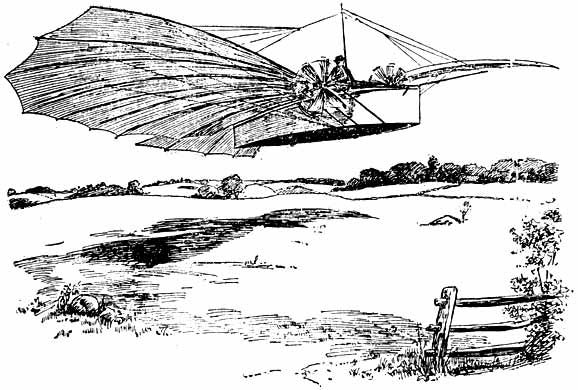

Wait, who’s this Langley guy who supposedly beat Whitehead into the air? This would be Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley. He wasn’t some obscure Ohio bicycle builder or immigrant tinkerer in Connecticut. He was an important figure whose aviation research was funded by the U.S. Army and conducted his tests over the Potomac River. Langley had repeatedly demonstrated “the possibility of mechanical flight” since 1896, when he launched an unmanned plane from a houseboat in Virginia and flew it some distance. He repeated the feat over the next few years.

Langley then worked on a full-scale, manned version of his Aerodrome. He made two attempts to fly it, both of which predated the Wrights’ Kitty Hawk flights. Both are now considered failures; the aircraft fell into the Potomac both times without traveling very far.

Some claim that a New Zealand farmer named Richard Pearse beat the Wright brothers, but his achievements were unknown at the time. Pearse — like the Wrights, a bicycle maker — supposedly flew his airplane several times in the spring and summer of 1903, months before Kitty Hawk. If these flights did happen, they didn’t get any press attention, but dozens of eyewitnesses later claimed to have seen Pearse flying a few hundred meters in 1903 before crashing into a hedge.

Pearse himself, however, gave credit to the Wrights in later interviews, saying that he hadn’t “attempted anything practical with the idea” before 1904 and that his early flights had not been successful (he may have been unaware of how equally unimpressive the Wrights’ early attempts were when he said this). As he aged, Pearse became increasingly isolated and paranoid; his erratic behavior, which eventually landed him in a mental institution, did not help his claims to have been an aviation pioneer.

One of the most interesting claimants in the race for the skies made his flight after the Wright brothers. The wealthy Brazilian coffee heir Alberto Santos-Dumont had been using his fortune to take to the skies for years by 1903. After a trip to Paris, the capital of hot-air ballooning, he built a series of balloons and airships in the 1890s. He flew his first heavier-than-air plane, the 14-bis, in Paris in September 1906.

Why, if Santos-Dumont was three years late to the party, do many Brazilians still claim that he was the first?

Well, some claim that the Wrights’ earliest flights were secret and could not be corroborated. Their first public demonstration in May 1904 was a flop — the motor wouldn’t start. Meanwhile, Santos-Dumont was rich and famous, and his exploits were well-covered. He made his flights in public view in Paris, in front of officials from the Aero Club de France (this ignores the Wrights’ 39-minute flight in 1905, which was conducted in front of hundreds in Dayton).

Others emphasize the Wrights’ dependence on catapults to get their planes into the air, while Santos-Dumont’s planes got into the air under their own power. This, in the eyes of Santos-Dumont’s backers, makes his accomplishments more impressive than the Wright brothers’

So how did the world settle on the Wright brothers as the greatest pioneers in aviation?

It didn’t at first.

Many observers believed that flight was impossible, or that claimants like the Wrights had not sufficiently proven their claims. In December 1905, Scientific American wrote that “the only successful ‘flying’ that has been done this year — must be credited to the balloon type.” In 1906, it was still predicting that the first flight lay just around the corner, not three years in the past.

It wasn’t until 1908 that the Wrights definitively convinced the world that they were for real — by traveling to France and performing a two-minute flight in 1908 (after repairing the damage French customs workers had done to the plane). The Wrights’ control systems were much more advanced than anything Europeans had seen, and observers acknowledged that the Wright brothers had the most sophisticated flying machines in the world.

A month later, the brothers demonstrated their plane for the U.S. Army, which had long doubted the Wrights’ claims. The flights impressed American officials, although one would crash, killing an Army observer and injuring Orville.

By 1909, the Wright brothers were heroes. The city of Dayton threw them a huge parade in June, complete with a “living flag” made up of 2,000 children.

It seemed that everyone was convinced — except for the Smithsonian, the home of the Wrights’ rival, Samuel Langley. In 1914, the museum, which housed Langley’s ill-fated Aerodrome, lent the craft to motorcycling and aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss was not a neutral in the aviation wars — he had been embroiled in a bitter patent dispute with the Wrights over the control systems in their airplanes.

Curtiss modified the Aerodrome and managed to make it fly for a few seconds. This allowed him, Langley, and the Smithsonian to claim that Langley’s plane had been “capable” of flight and therefore counted as the first airplane.

Orville Wright (Wilbur had died in 1912), tried to remain aloof for a while, but the lack of recognition irritated him more with the passage of time. By the 1920s, he was writing letters to anyone who he thought might be able to help him, including former president (and Ohio native) William Howard Taft.

Eventually, he sent the original Wright Flyer to a museum in London out of spite. He wrote the museum that

I believe my course in sending our Kitty Hawk machine to a foreign museum is the only way of correcting the history of the flying-machine, which by false and misleading statements has been perverted by the Smithsonian Institution.

In its campaign to discredit others in the flying art, the Smithsonian has issued scores of these false and misleading statements.…

With this machine in any American museum the national pride would be satisfied; nothing further would be done and the Smithsonian would continue its propaganda. In a foreign museum this machine will be a constant reminder of the reasons of its being there…

Your regret that this old machine must leave our country can hardly be so great as my own.

In the 1930s, Charles Lindbergh got involved in the dispute, suggesting a blue-ribbon committee to study the matter. Wright rejected the proposal. He stubbornly insisted that the Smithsonian admit that Langley’s machine had been heavily altered for the flights in 1914.

Over time, the Smithsonian’s position began to look silly. The Wrights’ plane was widely assumed to have been the first to fly. Why was the museum being such a stick in the mud about it?

The museum only reversed its position after the death of Orville Wright in 1948. Wright’s biographer had been working as an intermediary between the Smithsonian and Wright for years. Wright’s executors, acting on an unsigned draft of a will in which Orville had considered bequeathing the plane to the Smithsonian, allowed the museum to have it under one condition — the Smithsonian was forced to sign a pledge never to recognize that any other vehicle was capable of flight before the Wrights’ tests at Kitty Hawk.

The Smithsonian signed, and the matter was settled. As a matter of legal agreement and consensus, the Wright brothers were first. Their struggle for recognition — which only ended in the age of the jet and the rocket — had lasted much longer than it had taken them to invent flight in the first place.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

Share Looking Through the Past

Share Looking Through the Past

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!

.png)