If you live in the United States today, and you accidentally knock a hole in your wall, it’s probably cheaper to buy a flatscreen TV and stick it in front of the hole, compared to hiring a handyman to fix your drywall. (Source: Marc Andreessen.) This seems insane; why?

Well, weird things happen to economies when you have huge bursts of productivity that are concentrated in one industry. Obviously, it’s great for that industry, because when the cost of something falls while its quality rises, we usually find a way to consume way more of that thing - creating a huge number of new jobs and new opportunities in this newly productive area.

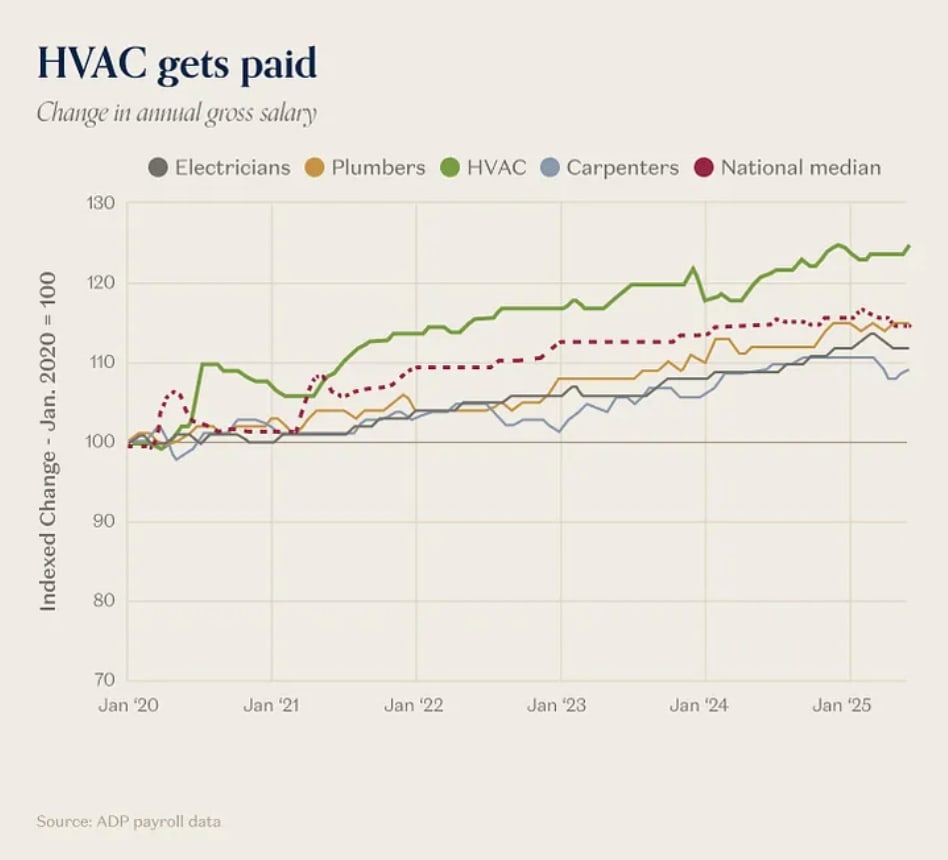

But there’s an interesting spillover effect. The more jobs and opportunities created by the productivity boom, the more wages increase in other industries, who at the end of the day all have to compete in the same labor market. If you can make $30 an hour as a digital freelance marketer (a job that did not exist a generation ago), then you won’t accept less than that from working in food service. And if you can make $150 an hour installing HVAC for data centers, you’re not going to accept less from doing home AC service.

This is a funny juxtaposition. Each of these phenomena have a name: there’s Jevons Paradox, which means, “We’ll spend more on what gets more productive”, and there’s the Baumol Effect, which means, “We’ll spend more on what doesn’t get more productive.” And both of them are top of mind right now, as we watch in awe at what is happening with AI Capex spend.

As today’s AI supercycle plays out, just like in productivity surges of past decades, we’re likely going to see something really interesting happen:

Some goods and services, where AI has relatively more impact and we’re able to consume 10x more of them along some dimension, will become orders of magnitude cheaper.

Other goods and services, where AI has relatively less impact, will become more expensive - and we’ll consume more of them anyway.

And, even weirder, we may see this effect happen within a single job:

Some parts of the job, automated by AI, will see 10x throughput at 10x the quality, while

Other parts of the job - the part that must be done by the human - will be the reason you’re getting paid, command a wildly high wage, and be the target of regulatory protection.

Let’s dive in:

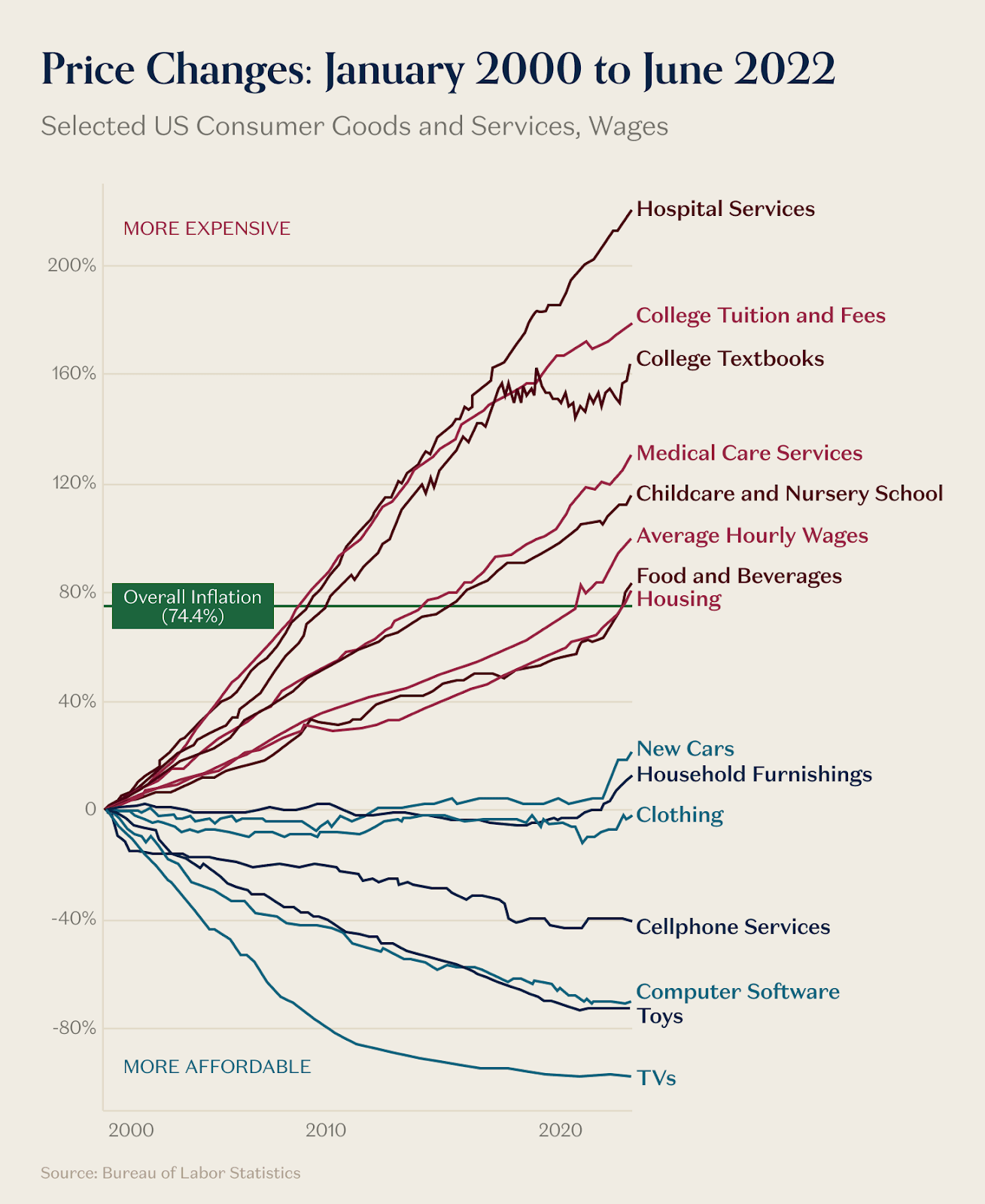

Chances are, you’ve probably seen a version of this graph at some point:

This graph can mean different things to different people: it can mean “what’s regulated versus what isn’t” to some, “where technology makes a difference” to others. And it’s top of mind these days, as persistent inflation and the AI investment supercycle both command a lot of mindshare.

To really understand it, the best place to start isn’t with the red lines. It’s with the blue lines: where are things getting cheaper, in ways that create more jobs, more opportunity, and more spending?

The original formulation of “Jevons paradox”, by William Stanley Jevons in 1865, was about coal production. Jevons observed that, the cheaper and faster we got at producing coal, the more coal we ended up using - demand more than eclipsed the cost savings, and the coal market grew rapidly as it fed the Second Industrial Revolution in England and abroad.

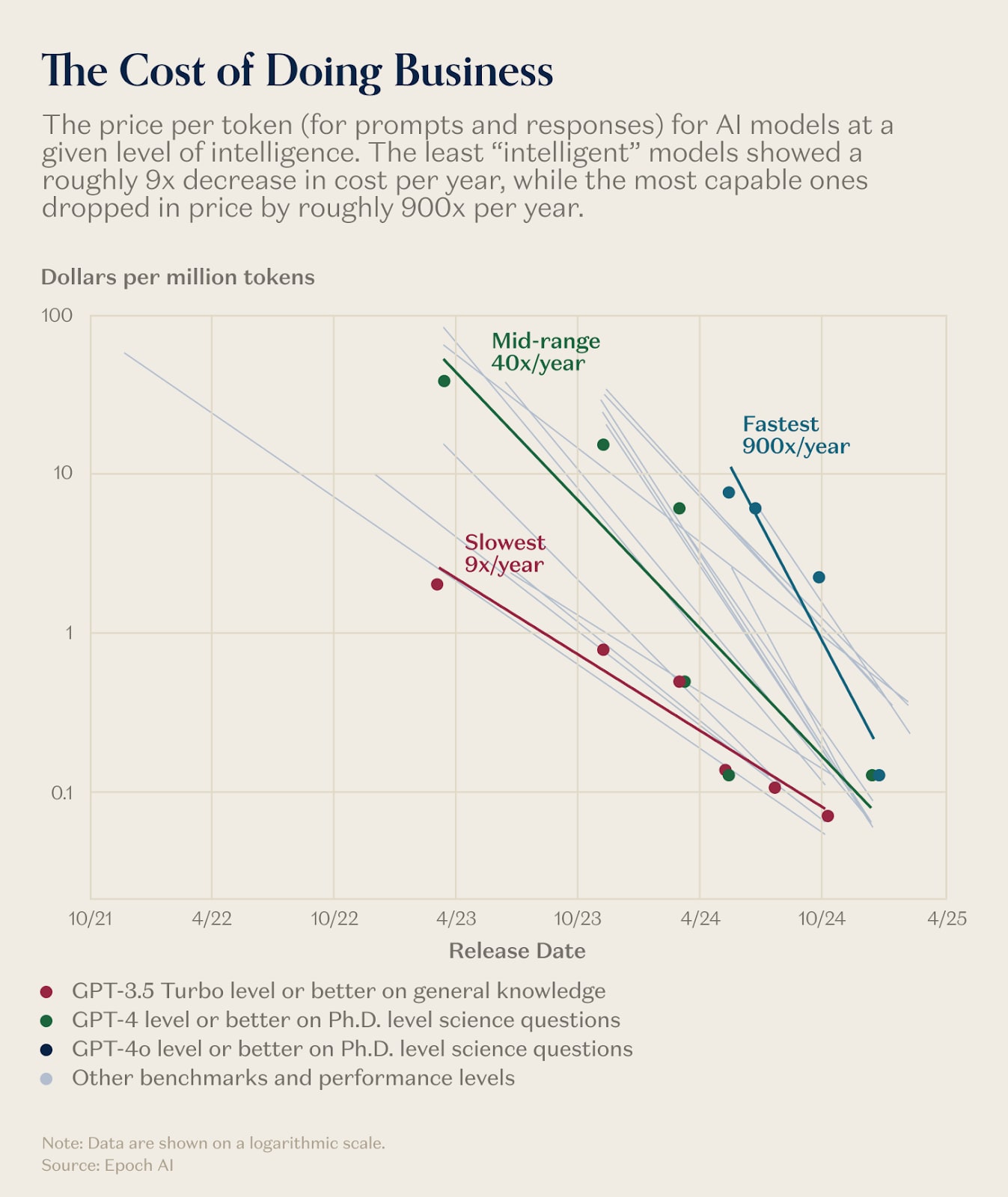

Today we all know Moore’s Law, the best contemporary example of Jevons paradox. In 1965, a transistor cost roughly $1. Today it costs a fraction of a millionth of a cent. This extraordinary collapse in computing costs – a billionfold improvement – did not lead to modest, proportional increases in computer use. It triggered an explosion of applications that would have been unthinkable at earlier price points. At $1 per transistor, computers made sense for military calculations and corporate payroll. At a thousandth of a cent, they made sense for word processing and databases. At a millionth of a cent, they made sense in thermostats and greeting cards. At a billionth of a cent, we embed them in disposable shipping tags that transmit their location once and are thrown away. The efficiency gains haven’t reduced our total computing consumption: they’ve made computing so cheap that we now use trillions times more of it.

We’re all betting that the same will happen with the cost of tokens, just like it happened to the cost of computing, which in turn unlocks more demand than can possibly be taken up by the existing investment. The other week, we heard from Amin Vahdat, GP and GM of AI and Infrastructure at Google Cloud, share an astonishing observation with us: that 7 year old TPUs were still seeing 100% utilization inside Google. That is one of the things you see with Jevons Paradox: the opportunity to do productive work explodes in possibility. We are at the point in the technology curve with AI where every day someone figures out something new to do with them, meaning users will take any chip they can get, and use it productively.

Jevons Paradox (which isn’t really a paradox at all; it’s just economics) is where demand creation comes from, and where new kinds of attractive jobs come from. And that huge new supply of viable, productive opportunity is our starting point to understand the other half of our economic puzzle: what happens everywhere else.

Agatha Christie once wrote that she never thought she’d be wealthy enough to own a car, or poor enough to not have servants. Whereas, after a century of productivity gains, the average American middle-class household can comfortably manage a new car lease every two years, but needs to split the cost of a single nanny with their neighbors.

How did this happen? 100 years after Jevons published his observation on coal, William Baumol published a short paper investigating why so many orchestras, theaters, and opera companies were running out of money. He provocatively asserted that the String Quartet had become less productive, in “real economy” terms, because the rest of the economy had become more productive, while the musicians’ job stayed exactly the same. The paper struck a nerve, and became a branded concept: “Baumol’s Cost Disease”.

This is a tricky concept to wrap your head around, and not everyone buys it. But the basic argument is, over the long run all jobs and wage scales compete in the labor market with every other job and wage scale. If one sector becomes hugely productive, and creates tons of well-paying jobs, then every other sector’s wages eventually have to rise, in order for their jobs to remain attractive for anyone.

The String Quartet is an odd choice of example, because there are so many ways to argue that music has become more productive over the past century: recorded and streaming music have brought consumption costs down to near zero, and you could argue that Taylor Swift is “higher quality” for what today’s audiences are looking for (even if you deplore the aesthetics.) But the overall effect is compelling nonetheless. As some sectors of the economy get more attractive, the comparatively less attractive ones get more expensive anyway.

Once you’ve heard of Baumol’s, it’s like you get to join a trendy club of economic thinkers who now have someone to blame for all of society’s problems. It gets to be a successful punching bag for why labor markets are weird, or why basic services cost so much - “It’s a rich country problem.”

But the odd thing about Baumol’s is how rarely it is juxtaposed with the actual driving cause of those productivity distortions, which is the massive increase in productivity, in overall wealth, and in overall consumption, that’s required for Baumol’s to kick in. In a weird way, Jevons is necessary for Baumol’s to happen.

For some reason, we rarely see those two phenomena juxtaposed against each other, but they’re related. For the Baumol Effect to take place as classically presented, there must be a total increase in productive output and opportunity; not just a relative increase in productivity, from the booming industry and the new jobs that it creates. But when that does happen, and we see a lot of consumption, job opportunities, and prosperity get created by the boom, you can safely bet that Baumol’s will manifest itself in faraway corners of the economy. This isn’t all bad; it’s how wealth gets spread around and how a rising tide lifts many boats. (There’s probably a joke here somewhere that Baumol’s Cost Disease is actually the most effective form of Communism ever tried, or something.)

So, to recap:

“Jevons-type effects” created bountiful new opportunity in everything that got more productive; and

“Baumol-type effects” means that everything that didn’t get more productive got more expensive anyway, but we consume more of it all the same because society as a whole got richer.

As explained in one job: our explosion of demand for data centres means there’s infinite work for HVAC technicians. So they get paid more (even though they themselves didn’t change), which means they charge more on all jobs (even the ones that have nothing to do with AI), but we can afford to pay them (because we got richer overall, mostly from technology improvements, over the long run). Furthermore, the next generation of plumber apprentices might decide to do HVAC instead; so now plumbing is more expensive too. And so on.

Now let’s think about what’s going to happen with widespread AI adoption, if it pays off the way we all think it will. First of all, it’s going to drive a lot of productivity gains in services specifically. (There is precedent for this; e.g. the railroads made the mail a lot more productive; the internet made travel booking a lot more productive.) Some services are going to get pulled into the Jevons vortex, and just rapidly start getting more productive, and unlocking new use cases for those services. (The key is to look for elastic-demand services, where we plausibly could consume 10x or more of the service, along some dimension. Legal services, for example, plausibly fit this bill.)

And then there are other kinds of services that are not going to be Jevons’ed, for some reason or another, and for those services, over time, we should expect to see wildly high prices for specific services that have no real reason to AI whatsoever. Your dog walker has nothing to do with AI infrastructure; and yet, he will cost more. But you’ll pay it anyway; if you love your dog.

The last piece of this economic riddle, which we haven’t mentioned thus far, is that elected governments (who appoint and direct employment regulators) often believe they have a mandate to protect people’s employment and livelihoods. And the straightforward way that mandate gets applied, in the face of technological changes, is to protect human jobs by saying, “This safety function must be performed or signed off by a human.”

When this happens (which it certainly will, across who knows how many industries, we’ll see a Baumol’s type effect take hold within single jobs. Here’s Dwarkesh, on his recent interview with Andrej Karpathy: (Excerpted in full, because it’s such an interesting thought):

“With radiologists, I’m totally speculating and I have no idea what the actual workflow of a radiologist involves. But one analogy that might be applicable is when Waymos were first being rolled out, there’d be a person sitting in the front seat, and you just had to have them there to make sure that if something went really wrong, they’d be there to monitor. Even today, people are still watching to make sure things are going well. Robotaxi, which was just deployed, still has a person inside it.

Now we could be in a similar situation where if you automate 99% of a job, that last 1% the human has to do is incredibly valuable because it’s bottlenecking everything else. If it were the case with radiologists, where the person sitting in the front of Waymo has to be specially trained for years in order to provide the last 1%, their wages should go up tremendously because they’re the one thing bottlenecking wide deployment. Radiologists, I think their wages have gone up for similar reasons, if you’re the last bottleneck and you’re not fungible. A Waymo driver might be fungible with others. So you might see this thing where your wages go up until you get to 99% and then fall just like that when the last 1% is gone. And I wonder if we’re seeing similar things with radiology or salaries of call center workers or anything like that.”

Just like we have really weird economies in advanced countries (where we can afford supercomputers in our pockets, but not enough teachers for small class sizes), we could see a strange thing happen where the last 1% that must be a human in a job (the “Dog Walker” part, as opposed to the “Excel” part) becomes the essential employable skillset.

In an interesting way, this hints at where Baumol’s will finally run out of steam - because at some point, these “last 1% employable skills” no longer become substitutable for one another. They’ll become strange vestigial limbs of career paths; in a sense. We have a ways to go until we get there, but we can anticipate some very strange economic & political alliances that could get formed in such a world. Until then, let’s keep busy on the productivity part. Because that’s what matters, and what makes us a wealthy society - weird consequences and all.

Views expressed in “posts” (including podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individual a16z personnel quoted therein and are not the views of a16z Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. a16z Capital Management is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply any special skill or training. The posts are not directed to any investors or potential investors, and do not constitute an offer to sell — or a solicitation of an offer to buy — any securities, and may not be used or relied upon in evaluating the merits of any investment.

The contents in here — and available on any associated distribution platforms and any public a16z online social media accounts, platforms, and sites (collectively, “content distribution outlets”) — should not be construed as or relied upon in any manner as investment, legal, tax, or other advice. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Any charts provided here or on a16z content distribution outlets are for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, posts may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein. All content speaks only as of the date indicated.

Under no circumstances should any posts or other information provided on this website — or on associated content distribution outlets — be construed as an offer soliciting the purchase or sale of any security or interest in any pooled investment vehicle sponsored, discussed, or mentioned by a16z personnel. Nor should it be construed as an offer to provide investment advisory services; an offer to invest in an a16z-managed pooled investment vehicle will be made separately and only by means of the confidential offering documents of the specific pooled investment vehicles — which should be read in their entirety, and only to those who, among other requirements, meet certain qualifications under federal securities laws. Such investors, defined as accredited investors and qualified purchasers, are generally deemed capable of evaluating the merits and risks of prospective investments and financial matters.

There can be no assurances that a16z’s investment objectives will be achieved or investment strategies will be successful. Any investment in a vehicle managed by a16z involves a high degree of risk including the risk that the entire amount invested is lost. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by a16z is available here: https://a16z.com/investments/. Past results of a16z’s investments, pooled investment vehicles, or investment strategies are not necessarily indicative of future results. Excluded from this list are investments (and certain publicly traded cryptocurrencies/ digital assets) for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly. As for its investments in any cryptocurrency or token project, a16z is acting in its own financial interest, not necessarily in the interests of other token holders. a16z has no special role in any of these projects or power over their management. a16z does not undertake to continue to have any involvement in these projects other than as an investor and token holder, and other token holders should not expect that it will or rely on it to have any particular involvement.

With respect to funds managed by a16z that are registered in Japan, a16z will provide to any member of the Japanese public a copy of such documents as are required to be made publicly available pursuant to Article 63 of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act of Japan. Please contact [email protected] to request such documents.

For other site terms of use, please go here. Additional important information about a16z, including our Form ADV Part 2A Brochure, is available at the SEC’s website: http://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov

.png)