Every morning, from 9-10am, I watch CNBC, or as much as I can stand. That’s when anchor Jim Cramer does his rant about the state of the world, and Cramer reflects the conventional wisdom of CEOs. Of late, Cramer’s been discussing deflation, a result, he argues, of the emergence of generative artificial intelligence displacing jobs. Lawyers, graphic designers, accountants, artists, writers, and white collar employees of all sorts are disappearing in this wave of automation. That will reduce the amount of cash going to workers, who will spend less. It will also increase productivity. So less cash for more stuff means lower prices, or a lower rate of inflation.

It’s not just Cramer. Amazon, JP Morgan, and Ford are all predicting the jobs apocalypse. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, whose company has absorbed a bunch of ex-Biden staff, says one scenario is that most entry-level white collar jobs disappear. "Cancer is cured, the economy grows at 10% a year, the budget is balanced,” he said, “and 20% of people don't have jobs." Here’s Ford CEO Jim Farley saying we need to prepare, and do more training of blue collar machine shop workers, people who move and fix what he calls the “essential economy.”

Is AI really replacing our workforce? Is this technology really a social asteroid about to hit the American office? Will we see a big productivity boost due to AI? Certainly AI is transformative, but the framing of the discussion is, in my view, wrong.

But before getting to that, I’d like to fully describe the politics of the “AI is taking the jobs” framing. In the political world, the conversation about AI is no less dire than it is on CNBC. The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, the New York Times’s Kevin Roose, and Trump advisor Steve Bannon are on board with the theory of the jobs apocalypse. "I don't think anyone is taking into consideration how administrative, managerial and tech jobs for people under 30 — entry-level jobs that are so important in your 20s — are going to be eviscerated," said Bannon.

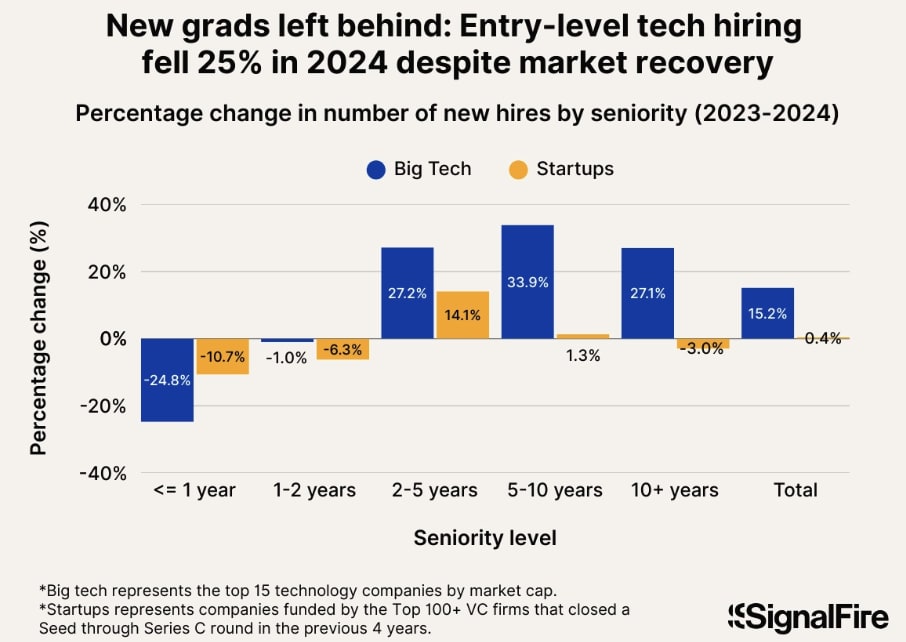

Here’s the chart of the “new grad gap” that Thompson put forward in his piece, which shows how easy it is for new college grads to get a job versus the total population. A college degree used to be a ticket to a job, goes the thesis, now it’s not. One reason, Thompson posits, is that it’s easy to replace a new college graduate with an AI system.

LinkedIn executive Aneesh Raman warned that AI is “breaking the bottom rung of the career ladder,” a frequently cited quote. It’s a real thing. And I’ve spoken with a few corporate leaders who have done just that, though there’s an important wrinkle that I’ll get to.

Former National Economic Council member Bharat Ramamurti takes this problem very seriously. “Estimates vary, but at the high end, both Goldman Sachs and McKinsey project that roughly 7% of American jobs—almost 12 million—could be fully replaced by AI within the next decade,” he writes. It could accelerate badly if we go into recession, which seems correct. There are also geographic and age-based impacts as well, as Ramamurti notes.

So what to do? Ramamurti’s suggestion is, broadly speaking, to empower workers. He’d like to see more collective bargaining to allow for a more collaborative rule-writing, such as what happened when Writers Guild West got new AI-rules in its agreement with the studios.

Consider the 2023 Writers Guild of America strike. The strike led to the successful negotiation of AI usage protocols requiring studios to disclose AI use to the public, prohibiting studios from using AI to generate original content in place of human writers, and barring studios from requiring writers to use AI to help create content. In that case, the existence of a unionized workforce permitted workers to bargain directly with management and protect their core interests—including their continued ability to engage in the artistic expression of writing—in the face of potential AI adoption.

America is not a unionized country, by and large, so Ramamurti suggests more direct policy intervention. Sectoral bargaining, where all workers in a specific industry segment set wages and conditions, is one answer. Another is co-determination, where a worker gets put on the board of directors of a firm, or specific feedback mechanisms for workers to have input into corporate AI systems. Another idea is to tax corporations more aggressively, as a way of moving some of the gains from AI productivity to the public writ large.

These are all good ideas, and I endorse them.

But I find the policy discussion about AI to be… incomplete. I’m reminded a bit of Presidential candidate Andrew Yang’s assertion in 2020 that America would soon run out of jobs, and therefore we need universal basic income or some sort of fiscal transfer approach, to the furrowed nods of the policy discourse wonks. Just a year later, we experienced a huge “labor shortage,” with all those who had discussed the end of work pretending they never said anything of the sort. Now it seems we’re back to the Yang days. It’s not that there won’t be a significant transformation in the nature of many jobs, or a productivity boost that displaces jobs or industries. But a job is just a problem we give people green pieces of paper to solve. Will we run out of problems? I don’t think so. If we choose not to solve problems, it will be just that, a choice.

Let’s start with the premise of the discussion, which is that there’s something unique going on with the introduction of a new transformational technology that is changing the trajectory of our society. Here’s the Thompson chart again. Notice something?

The decline started going down years before generative AI became thing. The narrative of AI taking jobs, while perhaps true, is certainly not all that’s going on. There is also a lot of evidence the AI taking jobs narrative just isn’t determinative, such as the fact that hiring in tech is now up.

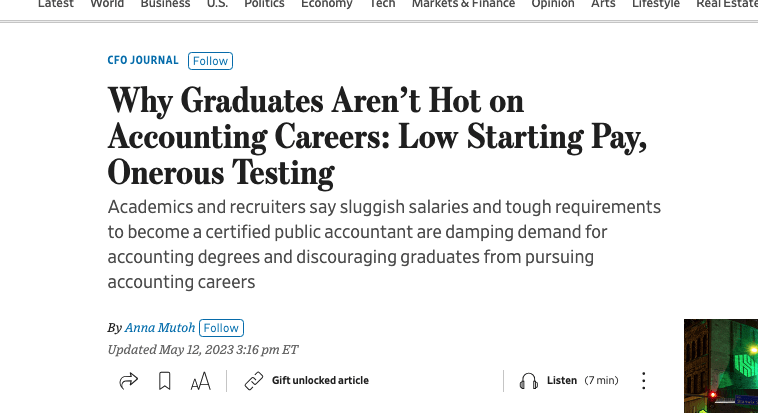

There’s more. If you look at jobs that are supposedly going to be replaced by AI, like accounting, you’ll see that years ago, before AI hit, there was already significant pressure. The reason had nothing to do with AI. Salaries suck, workload is high, and the prestige of the profession has declined as accountants have less power to stand up to the dishonest corporate leaders they are supposed to audit. These are preexisting political problems.

There are other aspects of the introduction of generative AI suggesting that the new systems themselves aren’t doing the transforming. Hertz, for instance, is using AI systems that over-estimate damages to rental cars, with the frustrating additional feature that customers can’t complain to anyone because customer service is also now handled by generative AI. That’s not an engineering story, it’s a story of customers being unable to sue for deceptive conduct because of mandatory arbitration agreements. It’s also a monopoly story; Hertz consolidated the rental car industry in the early 2010s, so consumers and workers have little choice. Is it truly important that Hertz now also has AI as a tool to reportedly annoy and cheat customers?

There are other elements of theft and or unfair behavior that too often go unremarked in the “AI conversation.” The technology itself is engineered through political choices. Last week, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on AI and copyright, showing how firms like Meta steal the intellectual work of authors and exploit it, without compensation. And I don’t mean they buy the books and feed them into a learning algorithm, they literally used pirated work to train their model, which their own employees question as possibly illegal.

Here’s novelist and former trial lawyer David Baldacci explaining how OpenAI, in his words, “backed up a truck to his imagination and stole everything he ever created.” These services now spit out novels that read as if they were written by Baldacci, with similar plots, dialogues, and even character names. This dynamic is broader than just one novelist; the number of cheap knock-offs is so high that online vendors are now putting weekly limits on how many books one individual is allowed to “publish.” I highly recommend watching Baldacci, who is quite persuasive. He’s a man whose job isn’t being replaced, so much as his work is being stolen. And that’s a political and legal choice about how we design the technology itself.

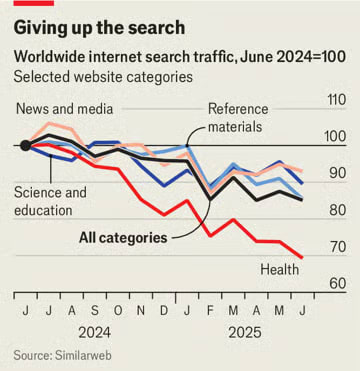

Many industries are undergoing similar predatory shifts, but with AI as an excuse. There’s an attempt to consolidate home buying, with several would-be monopolists trying to knock out realtors from the market, with AI as the excuse. There’s also this observation, from the Economist, on the death blow to publishers: Google is absorbing the web into its AI Now search feature that summarizes webpages.

The bigger problem, however, is that most of the internet’s hundreds of millions of domains are too small to either woo or sue the tech giants. Their content may be collectively essential to AI firms, but each site is individually dispensable. Even if they could join forces to bargain collectively, antitrust law would forbid it. They could block AI crawlers, and some do. But that means no search visibility at all.

Once again, this story is presented as an AI problem, but it’s not. It’s a political problem, notably antitrust law prevents smaller firms from bargaining with a monopolist. That’s been killing newspapers for years! Fortunately, there is actually legislation to allow collective bargaining by publishers, and it nearly passed Congress. Canada and Australia have a version of it, California nearly did. There is also an antitrust suit against the monopolist itself, Google. The reason Google can absorb published content is because publishers have to allow it. In order to appear in Google search, Google mandates letting the company crawl your content and train its AI. That’s a tying problem, a legal issue, not a technology issue. In the remedy proposal, that would prevent Google from stealing the content of publishers!

We’ve seen a technology substituted for politics story before, many times. Napster and file sharing were blamed for killing record labels. Today, streaming means labels are bigger and more profitable than ever, only artists and consumers have lost power, because the legal framework is different. But now we’re seeing that it’s the law, not the engineering, that structured what ‘jobs’ are in music.

There is in fact a common habit of powerful monopolists choosing to point out a supposedly neutral larger-than-life force, such as ‘technology’ or ‘the future’ or ‘disruption’ or ‘globalization’ to argue that they are not responsible for the anti-social policies enabling their market power. For instance, in 2013, there were a lot of complaints about Amazon avoiding sales taxes and engaging in predatory behavior around book pricing. How did Jeff Bezos answer this charge? “Amazon is not happening to book selling,” he said, “the future is happening to book selling.” I see a lot of similarities between that political language and the AI discourse.

And that gets me to my final observation. I had an interesting conversation with a very good corporate leader that I respect, who is running a small business involving packaging and selling research, one with some market power because it’s in a particular niche. Generative AI, he told me, is a capital-friendly technology, not a labor-friendly one. He’s doing less hiring, because generative AI takes “the tedium” out of some of his employee workflow, reducing task time required by 40% or so. So he needs fewer workers. I asked him, are you lowering prices? Are you investing more in other products? The answer to both questions was no. He was not passing through the productivity gains to customers, because he didn’t have to.

In a competitive market, higher productivity should mean lower prices, higher wages or higher quality. But his market, and American markets, more generally, are not competitive. So the question of how AI will impact our society, at least in this case, is also a question of market structure, not just technology. And I’m not seeing a lot of recognization that monopoly power or the lack thereof dictates the gains from new engineering capacity. But then, I didn’t see that either when pundits said ‘the internet killed newspapers.’

Here’s what’s really going on. AI as a technology is transformational, but the “AI conversation” is just the latest excuse to pay people less money or engage in other forms of unfair business conduct. The answer isn’t an AI-specific response, it’s to promote competition, expand labor rights, including intellectual property protections for artists and engineers, protect consumers, provide financing for farming and small business, while taxing and otherwise creating friction for the movement of financial capital. That’s not just good policy because of AI, it’s good policy if you want any form of democracy!

Yet, today, American policy is organized around juicing higher returns on capital, which means policymakers focus on cutting wages, squeezing consumers, and reducing taxes on finance. This choice isn’t hidden, most of our leaders really believe that experts and financiers know how to organize America better, and much of our economic model is now based on higher asset prices. But these choices have been in place for decades, which is why we are afraid of job losses, instead of seeing the possibility of new industries and prosperity. It’s also why Americans are scared of AI; we rightly assume technology will conform to the larger politics of our society. When American policy was organized to benefit most of us, technology meant The Jetsons. Since it’s now organized to consolidate power, it’s become Black Mirror.

All of which is to say that we really should pay careful attention to generative AI. If it can cure cancer or automate driving, awesome. At the same time, companies like Meta and Anthropic, who steal en masse, should be held accountable for doing so. But in terms of policy, we have to distinguish between “AI as a technology” and generalized Wall Street-friendly choices causing the problems ascribed to AI, aka lower wages, less job stability, and people without power getting screwed.

So yes, we should decentralize power and empower people who work for a living, from entry level college graduates to novelists like David Balducci to truck drivers. And maybe the introduction of AI as a technology is a good excuse to do that. But that’s really no different than pointing out that we shouldn’t have foreclosed on tens of millions of people during the financial crisis, or that we should be organizing our overall policy regime on political economy to ensure a more democratic division of resources. In other words, there is no real policy answer to “AI is going to take our jobs,” because what that phrase really means is “America is treating working people like shit.” And to fix that, well, we have to break our national addiction to higher returns on capital, and then do something like the New Deal again.

If you are seeing AI transform your work or some aspect of your life, please let me know over email or in the comments. Here’s how I use it. When I have a bunch of documents, I’ll put them into a database and use an LLM to search through them. I also use them to transcribe interviews and as a supplement to search. On occasion, I’ll do image generation, though I’m not a big fan of the art they produce. And Google has stuck its AI Now feature on top of Google search result pages, so I’ll look at that because the user interface forces me to.

.png)