By now, most of us have, consciously or unconsciously, had some experience reading things written by AI — specifically, by Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT. If you’re like most readers, you tend not to like it.

ChatGPT, and other LLMs, have converged on a particular voice: use of verbs like “delve,” constructions like “it’s not X; it’s Y,” excessive use of parallel structures, and — of course — em-dashes galore.

There’s a cottage industry of articles and tools discussing the telltale signs that a piece of text was written by a machine.

It’s given some human writers, myself included, second thoughts about using an em-dash, even where one would be perfectly legitimate, simply to avoid the charge of writing “AI slop.”

It’s ironic, then, that the techniques used by LLMs have a long human history. I’m not going to defend “delve” or the overuse of the em-dash, but many techniques beloved of LLMs have long been considered marks of good rhetorical technique.

The problem is not that LLMs use these techniques: it’s that they’re so robotically consistent in how they use them that it becomes an abuse. What the LLM lacks is the taste to know when to deploy these techniques.

But let’s look at some of the classic “tells” that something was written by AI, and where they come from. Many, in fact, started out as textbook techniques of English writing and oratory, with deep roots in classical rhetoric.

You're reading The Dead Language Society. I'm Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

If you upgrade, you’ll also be able to join our ongoing Beowulf Book Club and watch our discussion of the first 400 lines right away.

Most of the techniques beloved of LLMs are versions of parallelism.

Parallelism is a rhetorical technique where you use the same kind of word, phrase, clause, or sentence in a row. In fact, I just used it in the previous sentence: word, phrase, clause, and sentence are all nouns that I put into a parallel structure.

Parallelism is common enough that most people use it from time to time without thinking. But LLMs use it compulsively. Rarely will an LLM say something is efficient without adding that it’s also reliable and effective. (We’ll return to this rule of threes later on.)

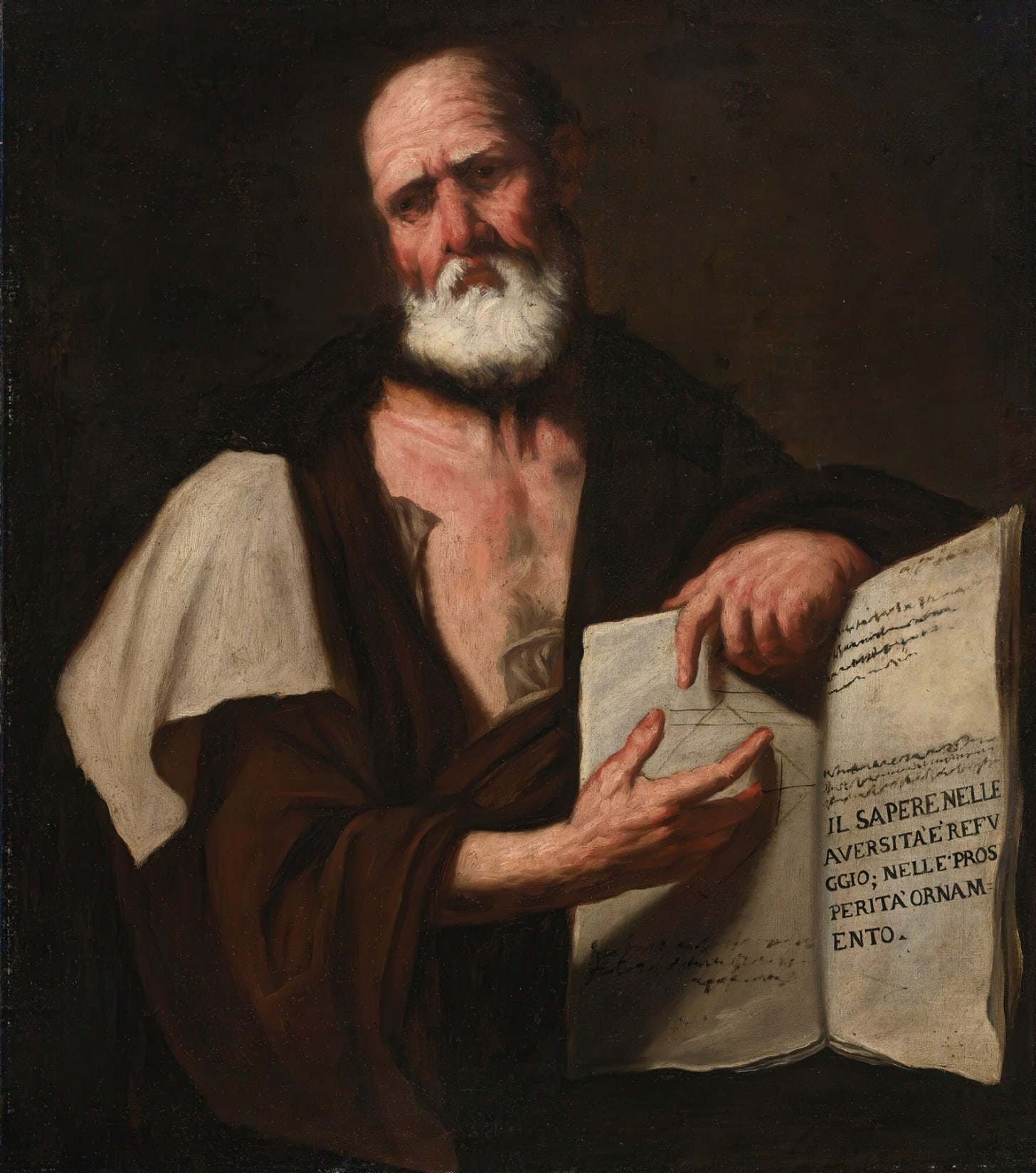

Like all of the techniques I mention, parallelism is not bad in itself. Churchill used it effectively in speech after speech:

I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat. (parallel words)

And, masterful orator that he was, Churchill could even nest parallelisms:

You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land, and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. (parallel words and phrases within parallel clauses)

But like any tool, parallelism can be overused. And LLMs are particularly guilty of this.

To get some examples for you, I asked Claude to write a letter convincing a friend to move to another city (Claude chose Portland for some reason). The result was littered with parallelisms. Here are some representative excerpts:

The food scene here is incredible – I know how much you love trying new restaurants. We have food truck pods on every corner, craft breweries that would blow your mind, and the best coffee culture outside of Seattle.

I think you'd absolutely thrive in the creative community here. Portland is full of artists, writers, and makers. There are co-working spaces, art galleries that actually showcase local talent, and maker spaces where you could finally start that pottery hobby you've been talking about.

Alberta Arts District would be perfect for you – walkable, eclectic, and full of character.

There’s nothing wrong with any of this parallelism (although Churchill it most certainly ain’t), but the effect it produces is monotonous.

Parallelism is a big umbrella term for many different techniques, some of which are particularly irresistible to LLMs. And it’s in these more specific techniques of parallelism that you see the limitations of LLM writing most clearly.

This must be the technique that LLMs love the most: it’s not X, it’s Y.

But this technique has a long human history too. It even has a fancy Greek name thanks to Aristotle: antithesis, literally ‘setting against.’ It works as its name suggests, by setting two seemingly contradictory ideas against each other in a parallel grammatical structure.

You’ll find antithesis used in lofty rhetoric, such as John F. Kennedy’s memorable line:

Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.

It’s in the Bible too:

I came not to send peace, but a sword. (Matthew 10:34, AV)

Both of these examples involve explicit negation in the first half of the antithesis, just like the LLM version: ask not vs. ask; not peace, but a sword.

These are wonderful examples of rhetoric, but, nevertheless, they’re the least subtle kind of antithesis: one that makes the contradiction between the two halves explicit with a not.

But you can write a subtler type of antithesis where the contradiction is only implicit, such as in Alexander Pope’s memorable phrase:

To err is human; to forgive, divine. (Pope, An Essay on Criticism, 525)

Here, the state of being human is contrasted with what Pope sees as its opposite: being divine.

And here’s one from Seinfeld:

Serenity now; insanity later. (Seinfeld 9:3, “The Serenity Now”)

This one is actually a double antithesis, since serenity is contrasted with insanity, and now is contrasted with later. Look at the economy the Seinfeld writers showed in that line: four words, two antitheses. Nothing more.

Antithesis tends to produce memorable lines, which is why it’s so jarring when it appears in every other paragraph of LLM-generated prose. What should be a rhetorical “special effect” ends up being used so frequently that it loses its special character and becomes monotonous.

Part of the problem is that LLM-generated antitheses tend to be the explicit kind, which use not or isn’t to make the contradiction explicit, rather than relying on the reader to realize the contrast: an AI Alexander Pope would have written: Forgiveness isn’t human — it’s divine.

Not good.

Now we come to another special case of parallelism: the rule of threes.

LLMs love putting things in sequences of threes, most likely because we humans do as well: Stop, drop, and roll; Faster, higher, stronger; Liberté, égalité, fraternité ‘Freedom, equality, brotherhood.’

The story of Goldilocks wouldn’t work as well if she had found the second bowl of porridge just right. Even I wrote this article describing three techniques, rather than two or four.

The Greeks and Romans realized how well this “rule of three” worked. The fancy name in Greek is tricolon, meaning ‘having three members.’ One of the most famous tricolons comes from the classical world, such as Julius Caesar’s Veni, vidi, vici ‘I came, I saw, I conquered’.

When the elements in a tricolon are of unequal size or complexity, it’s very common for them to be arranged from smallest to largest.

This is called an ascending tricolon, and you can find one in the American Declaration of Independence: Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Another one, Peace, order and good government, features in the British North America Act that created Canada. Nothing like an ascending tricolon to get a country started.

Both of these founding phrases are good examples of the ascending tricolon, since the phrases are ordered strictly by the number of syllables they contain: life (1 syllable), liberty (3 syllables), the pursuit of happiness (7 syllables).

The phrase wouldn’t work nearly so well if it were ordered like this: the pursuit of happiness, life, and liberty.

Like the other examples of parallelism I’ve been discussing, tricolon is everywhere in LLM-generated prose. To get some more examples, I asked Gemini about how LLMs tend to write. It told me this:

This style is not a random collection of errors or quirks but a coherent rhetorical posture, optimized through training and alignment to project authority, clarity, and inoffensiveness.

This one has a tricolon and ticks all the other boxes too: Antithesis (is not… but), ascending tricolon (albeit imperfectly ascending: authority, clarity, and inoffensiveness), and a miscellaneous parallelism (errors or quirks).

And this:

The emergent rhetoric of LLMs—impersonal, authoritative, and homogenized—has profound and paradoxical consequences.

Another imperfectly ascending tricolon (impersonal, authoritative, and homogenized), a parallelism (profound and paradoxical), but this time no antithesis. Do better, Gemini!

With this technique, as with the others, the issue is not the use, but the abuse. Tricolon is an effective technique, but if all you ever do is tricolon, the effect is dulled, blunted, and, believe it or not, lacking in intensity.

An LLM writes like someone who has just learned about all these sophisticated rhetorical devices and can’t wait to use them at every possible opportunity.

The LLM is a writer who has never heard the phrase less is more, and will use Churchillian rhetorical techniques even in mundane situations, like writing customer support emails.

The overall effect of this saturation of parallelism, antithesis, and tricolons ascending (or otherwise) is what the kids call “slop.” But when we look at the nuts and bolts of how LLMs write, we find that they’re deploying techniques we all admire, that is, when they’re done well.

What the LLM lacks is not technical ability, but taste. And taste is something that — at least as of the date of writing — we still need humans for.

.png)