Paul Hudson, @twostraws, October 22nd 2025

When I was a teen, I learned about computers by trying things, breaking things, and fixing them again – relentless curiosity and experimentation, backed up by computers being much more open to investigation, allowed me to learn and grow.

Today’s computers are a lot more polished and a lot more safe, and I get why – most folks don’t want to think about the command line, don’t care about binary, and don’t even know about packet sniffing.

But I’m really keen to bring back the same experiences I had for a new generation, so I decided to do something about it: I built a huge “capture the flag” game that teaches kids 13+ how to do SQL injection, how to use rainbow tables to figure out hashes, how to use steganography to hide data in images, and more.

My goal was to take just a little of the glorified theatre you usually see in movies – the look and feel of games I loved like Syndicate, Command & Conquer, and Uplink – and mix it in with real-world skills around networking, cryptography, digital forensics, and more, to create something that teaches kids core computer science skills in a fun way.

I want to talk about my goals when building the app, some of the challenges I hit, the technology that’s used, and more – I hope it’s useful!

If you want to skip the reading and just try the app yourself, click here.

What’s the problem?

There’s an abundance of “learn to hack” material already out there, but a lot of it has one or more problems:

- It can be dry and academic, focusing on reading theory and answering questions.

- It’s often available only to specific groups at specific times, e.g. national cybersecurity competitions.

- You get challenges that are very interesting, but no guidance how to solve them.

- They often use shared resources, so you can’t do things like rewrite database entries or delete files.

Some of these are inevitable – if you want a serious career in cybersecurity, you do need to sit down and study a whole lot of theory!

But together these problems can create an off-putting environment: students want to know they are dealing with real tools and technologies, but they also want a clear path, they want some guidance how to move forward, and they also want it to feel exciting, particularly when they are just starting out.

That’s the gap I’m trying to fill – to make something structured, with scaffolded challenges that feel cinematic but teach practical skills.

Building a safe place to break things

I decided to try building something that solved these problems. Something that:

- Provides 240 “capture the flag” challenges around things like SQL injection, the Linux command line, JavaScript, hashing, encryption, and more.

- Teaches students the core computing, security, and logic skills needed to solve all those challenges.

- Uses safe sandboxing, so that all data, servers, and hacks are done inside the game rather than affecting real targets.

My goal is not to turn everyone into a seasoned pentester overnight, but just to inspire a new generation of hackers to experiment, learn, and have fun in a safe and structured way.

As you might imagine, this took a lot of work.

Part of that work was building tools to simulate real-world data in a self-contained app – packet sniffing, network routing, DNS lookups, etc, all need to be able to work without the user leaving the app and even if they are offline. (I have cached DNS results for the servers used in challenges!)

But honestly the biggest part of the work was just crafting all the challenges. If this were a platform game I could just make the core game engine then put different levels in there. In contrast, cybersecurity challenges can’t repeat because it wouldn’t be fun – every challenge has to be more or less unique.

For example, in one challenge you need to discover that one PNG file actually contains several, another challenge mixes decimal/hex/octal ASCII values to spell a message, another one hides the flag in a regex crossword, and yet another one makes you log into a virtual email inbox to find the next target of a cybercriminal gang.

The end result is live now: it’s called Hacktivate, and it’s available on iPhone, iPad, and Mac.

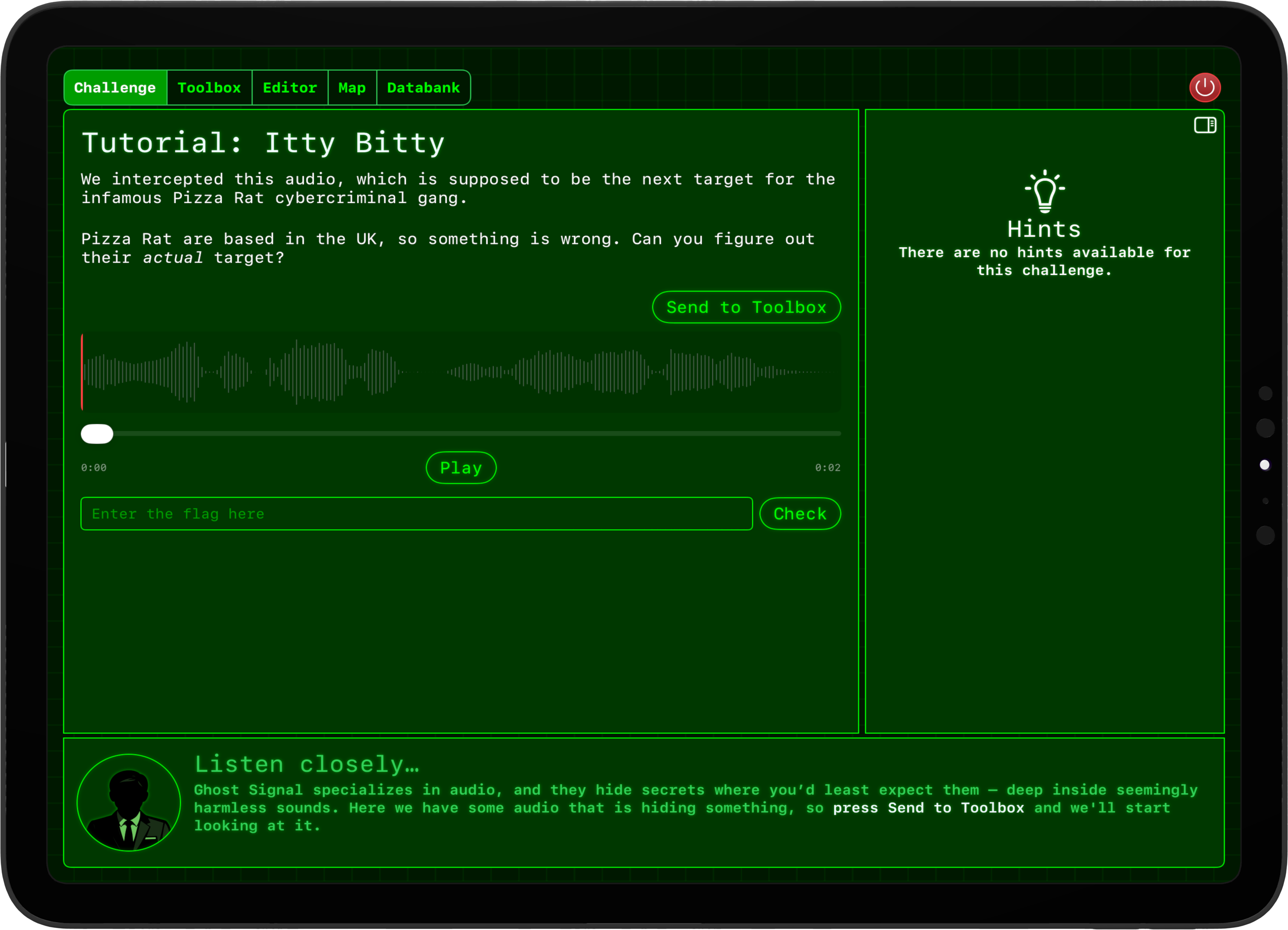

What hacking looks like inside Hacktivate

There are a whole bunch of different challenges in the game, but I want to pick out a handful of them and also talk about how they were implemented.

- Basic data-handling questions – hex, binary, ASCII, base64, and similar. These teach students about data representation, and were probably the easiest to make because it’s really just about them learning to recognize what things like hex look like.

- Cryptography challenges. These start out with classic codes and ciphers (Caesar, Vigenère, Morse, etc) but then move onto modern hashes and encryption with SHA1/2/3, Enigma, and AES. These got increasingly hard to make, because you want to give students just enough information to figure out the answer themselves without revealing too much.

- Browser-based challenges, all running locally on the user’s device. These start out trivial (passwords written in a HTML comment), move up through things like HTTP headers and cookies, then go onto to things like IDOR, SQL injection, and similar. These were surprisingly easy to make, mostly because there are so many web-based vulnerabilities to choose from 🫠 Internally the app runs a private web server so I can dynamically adjust page content as they progress through challenges.

- Terminal-based challenges, again all running locally on the user’s device. This was the hardest set of challenges to create, mostly because I need to ship the app on Apple’s platforms! So, I ended up creating a Linux terminal emulator, along with various core commands (ps, cat, netstat, nc, strings, sudo, etc), that lets me set up challenges such as rogue servers running, curious commands in the user’s history, files that are owned by different users, etc.

- Networking challenges. Again these start out quite simple (can you find the optimum route from A to B? Here are a bunch of IP addresses – which one contains the flag?), but then get tougher with things like packet sniffing, ARP spoofing, and similar.

- Steganography challenges, which are quite different from the regular cryptography challenges. As with the others these start out simple (“if you reverse the audio and speed it up you can hear a voice!”), but end up with more complex challenges – “if you read the least significant bits of this audio file and treat them all as grayscale image data, you get the flag.”

And those are just some of them.

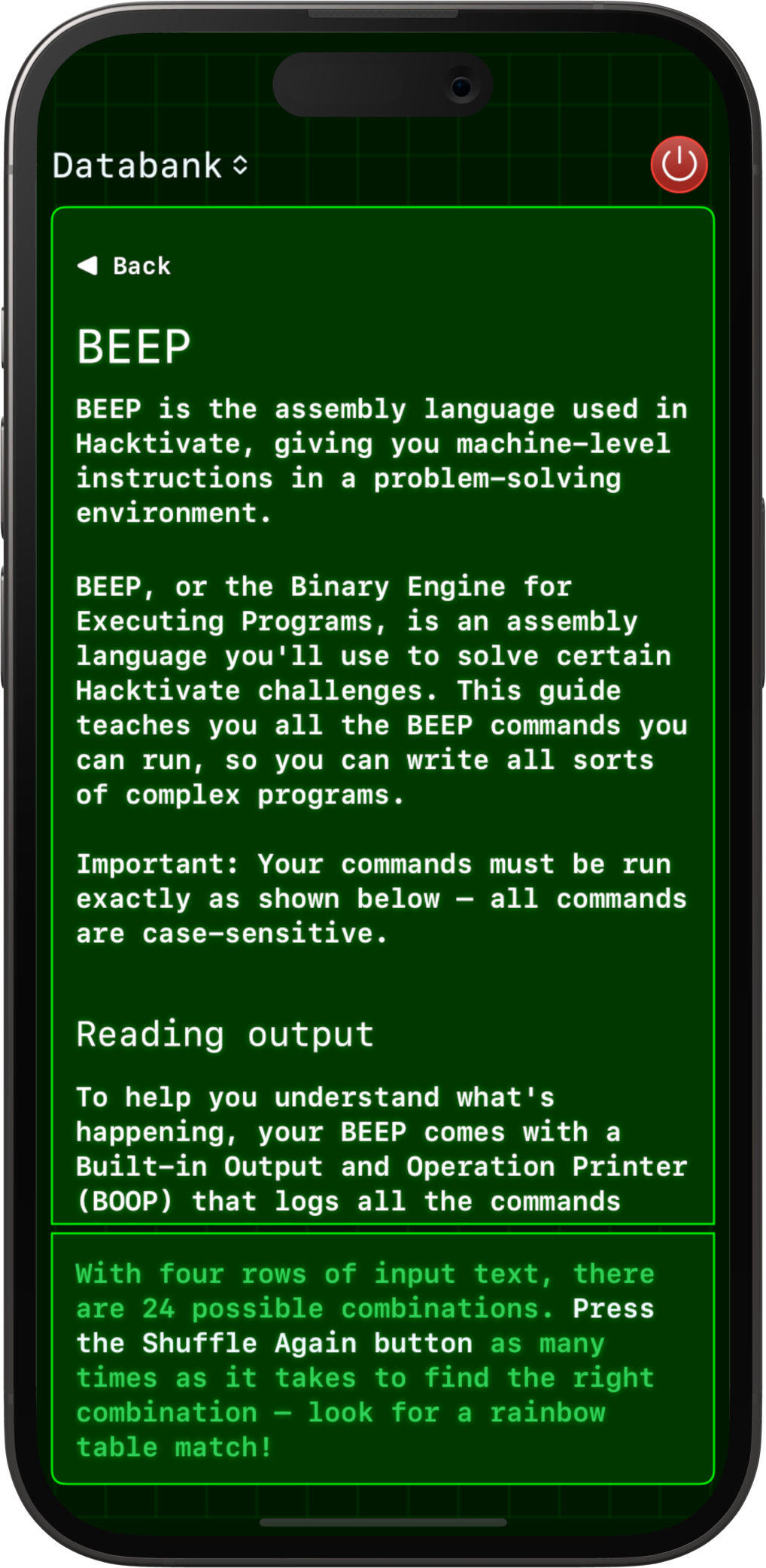

Students learn about regex crosswords, substitution ciphers, robots.txt, Unicode, OSINT, logic gates, and so much more. Heck, there’s a whole virtual assembly language used in some of the challenges!

No matter what the player does, one nice thing about the app running on a local device is that it’s completely private – there are no trackers, no analytics, no adverts, no cookies, or similar. Everything you do is private to you and only you.

Under the hood

The entire app is written in Swift and SwiftUI, which allows me to target iPhone, iPad, and Mac. I have no doubt that will make a certain group of people roll their eyes, but honestly Apple has been supportive every step of the way – they have provided lots of help and guidance to make the app the best it can be, even providing code-level support when I hit issues.

(And if you’re dead set against Apple devices, you should check out the web version of Hacktivate – it’s not as powerful or as fun, but it’s entirely web-based and free!)

Some AI was used in the creation of the app, but it was mainly in the app’s “toolbox” – it’s my own little version of CyberChef, where users can create recipes to transform data in a variety of ways to hunt for flags.

Some of the tools in this toolbox were hard to create, and AI did a fantastic job here. For example, the Enigma machine implementation was almost entirely AI, as were parsing SSH host keys, the SHA family of hashes, and transforming audio. These are fairly complex, precise algorithms, and – with some careful prompting – Claude did a great job of implementing them correctly.

However, the vast majority of the app was written by me, by hand, because AI just isn’t very good at being original. I wanted challenges that felt crafted and intentional, so that users could feel their progression grow over time, as opposed to just throwing out a couple of hundred random AI ideas.

The final tally, as of today: 45,132 lines of Swift code, 164,680 lines of JSON, plus some HTML, CSS, Markdown, etc. The JSON contains challenge information, but also all the simulated data – things like virtual email inboxes, terminal configurations, packet captures, etc, and even a whole social network that’s used in exactly one challenge.

Outside my own work, I worked with a few different designers from Fiverr on things like team and player icons, used open-source libraries such as SQift to let users manipulate a local database with SQL, and used Creative Commons media from Brad Sucks and similar, so that I had interesting things to hide flags inside.

I made a YouTube video walking through various parts of the Hacktivate code:

Influences from old-school games

Even though it’s powered by real-world skills, I wanted Hacktivate to get just a bit of the “Hollywood hacker” aesthetic – to be a bit retro and a bit cool, so that students felt it was more fun.

I was hugely inspired by three games I love:

- The core of the UI was hugely inspired by the game Syndicate by Bullfrog Productions. The green-screen UI, having screens draw themselves with a laser, the squared-off map with icons, etc; this was one of the first things I built, because I knew I wouldn’t continue unless I felt it was fun too.

- Other parts of the UI – particularly text rendering and animations – were inspired by Command & Conquer by Westwood Studios.

- Finally, the game Uplink by Introversion Software gave me lots of ideas, although our approach is quite different – they go hard down the Hollywood hacker route, whereas Hacktivate tries to stay anchored to real skills.

I think the result works well: the interface feels suitably fun and retro, there’s a light sprinkling of animation, particle effects, and haptics to add little bits of surprise and delight, and it still manages to cram in all the power tools people need to solve the challenges.

Here’s a video of the C&C installer from their remastered edition – I think the parallels are pretty clear!

Where it goes next

My goal is obviously not to create a horde of black hat hackers, but instead to create something that’s fun and engaging, to provide opportunities for students to learn in a safe way, and I hope also to inspire new people to consider cybersecurity as a career – with all the recent hacks on Jaguar Land Rover, Asahi, F5, and similar, the demand has never been higher.

But even if students just use it to have some fun, I at least hope it makes them better equipped to spot scams, secure their own data, and reason about online privacy.

There’s still plenty to improve in the app:

- Improving screenreader support is my #1 focus right now, so the game is as accessible as I can make it.

- I’m considering adding some sort of leaderboard system, although I want to make sure it’s done in a privacy-preserving way to match the rest of the app.

- I’d like to add support for achievements, badges, etc, as the user completes challenges. Apple offers Game Center for this, which would be a fun addition.

I’ll also keep trying to refine the iPhone UI. The app is really packed with functionality, and getting that down to a phone-sized screen was no mean feat.

Want to try it?

If you like puzzles, packet captures, or following breadcrumbs where they shouldn’t be, Hacktivate is live on the App Store.

You can try 10 tutorial challenges for free, and unlock 240 more with a one-time purchase. When you buy the unlock it works on all your Apple devices, with your progress automatically synced between them.

I’d love to hear what you think, or what kinds of challenges you’d like to see next!

.png)