Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’d like to sign up to receive issues over email, you can do so here.

In late May, JP Morgan’s chief investment strategist Michael Cembalest went on the podcast Odd Lots, to discuss the stock market with co-hosts Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway. He asked a question a lot of us have. Why haven’t the antitrust laws worked to constrain big tech, in particular Google? After all, there has been aggressive action against the firm from the first Trump administration, through Biden, and now with Gail Slater in the second Trump administration.

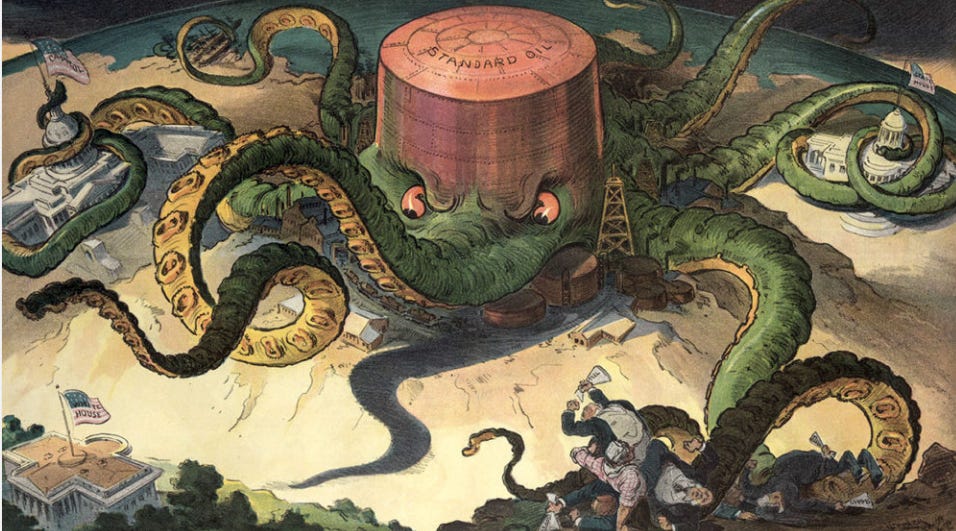

To answer this question, I spent some time going over the transcript for the last day of the Google antitrust trial, where the lawyers on both sides, and the judge, discussed what to do about Google’s illegal monopoly. At this point, Google has lost, and it’s just the remedy phase, so you would think we’d be hearing about the way to take apart its monopoly in search. In 1911, for instance, the Supreme Court broke up Standard Oil into 34 separate firms, including smaller random pieces that were only tangentially related to its acquisition or maintenance of monopoly.

Google is like Standard Oil in one sense; it has a lot of lines of business, most of which it acquired, that could be split apart into viable firms. But it’s unlike Standard Oil insofar as, much of what it does can be duplicated or cloned without damaging the original line of business. We usually hear in antitrust that digital technology makes it too hard for government to regulate, but in this case the opposite is actually the case. We could just clone Google search, whereas you can’t clone an oil pipeline or a refinery.

Yet cloning or divestments - with a few important exceptions - do not seem to be on the table now in the Google search trial. And in the discussion in court, we see why we haven’t been able to get a hold on global communications firms that are bigger by reach than any commercial endeavor that has ever existed in American history.

First, it’s important to lay out the scale of Google and its big tech brethren, which is not about tech, or media, but the entire economy writ large. On that Odd Lots episode, Weisenthal did so by bringing up a former guest of the podcast, a woman named Sarah LaFleur, the CEO of a fashion company. The cost to acquire a new customer, she complained to him, had gone from $13 to $250 over the course of a decade or so, largely because of increasing ad prices on Instagram. She tried alternatives to Instagram, but they didn’t work, because Meta’s monopoly, based on the acquisition of data and reach, was so much better than rivals. “One of the things that must be going on in the economy,” Weisenthal said to Cembalest, “is everybody's margin becoming Facebook's profits, or everybody's margins eventually becoming Alphabets profits.”

That’s right, said Cembalest, who laid out a host of statistics showing that the U.S. stock market, and really global stocks, are divided in two. There’s big tech, and everyone else. Big tech is massive and growing quickly, everyone else is smaller and growing more slowly. This dynamic is historically unusual because it doesn’t make much sense; as a firm becomes a trillion dollar behemoth, it should be harder to grow, not easier. And yet that does not seem to be the case for Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft, who reliably churn out double digit revenue increases. Cembalest pretty much said that big tech is gradually taking over everything in the economy, that these large firms own key “real estate” everyone must use.

That’s the view from one of the smarter minds on Wall Street; and in some ways, that’s how most Americans think about the law. It’s also reasonable. I’m going through old Supreme Court cases from the 1950s and 1960s, and the courts were clear that the penalty for a dominant firm who had broken antitrust law was to have its monopoly terminated and the fruits of that monopoly confiscated. Here’s the classic case United Shoe in 1968, in which the Supreme Court oversaw a shoe machinery company that had monopolized its market.

It is, of course, established that, in a monopolization case, upon appropriate findings of violation, it is the duty of the court to prescribe relief which will terminate the illegal monopoly, deny to the defendant the fruits of its statutory violation, and ensure that there remain no practices likely to result in monopolization in the future. See, e.g., United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U. S. 563, 384 U. S. 577 (1966); Schine Theatres v. United States, 334 U. S. 110, 334 U. S. 128-129 (1948). The trial court is charged with inescapable responsibility to achieve this objective.

United Shoe was a unitary company, meaning not the product of a set of mergers. Still, the Supreme Court told a lower court it had to be broken up. (Though often derided as radical, break-ups are routine on Wall Street.)

It was also well-established that judges could order wide-ranging remedies far afield of the original violation. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson noted this in a case called International Salt, in which a company that sold salt processing machines also forced customers to buy its salt for use in those machines, a violation of antitrust law known as “tying.” The court not only prohibited tying going forward, it also forced International Salt to lease its machines on a non-discriminatory basis to customers. International Salt objected, noting that such a remedy went beyond what it had done wrong.

In his ruling, Jackson said, essentially, that crime shouldn’t pay. It wasn’t enough for a court to stop the original violation, because monopolists built on their unlawful activities. Once a firm had come to dominate a market with sordid tactics, it could maintain that monopoly easily, using “methods more subtle and informed, and more difficult to prove, than those which, in the first place, win a market.” To that end, judges not only were allowed to foreclose a lot more activity than just the original misdeed, but should do so. “When the purpose to restrain trade appears from a clear violation of law,” he noted, “it is not necessary that all of the untraveled roads to that end be left open, and that only the worn one be closed.”

Break-ups, while not common, weren’t that unusual, and stiff remedies weren’t controversial; higher courts would sometimes overrule judges who weren’t harsh enough on lawbreakers, even for firms who had monopolized a relatively small industry. So that was then.

Today is different. Somehow, just a few firms are eating up all the margin in the economy, without being stopped. Google is even on the verge of buying yet another big firm, cybersecurity firm Wiz for $32 billion, and Meta is trying to acquire the guts of Scale AI for $14 billion. And it’s not that there’s no enforcement; Meta, Apple, Google, and Amazon are all facing antitrust cases, both public and privately brought. And again, Google has even lost three of them. So what gives?

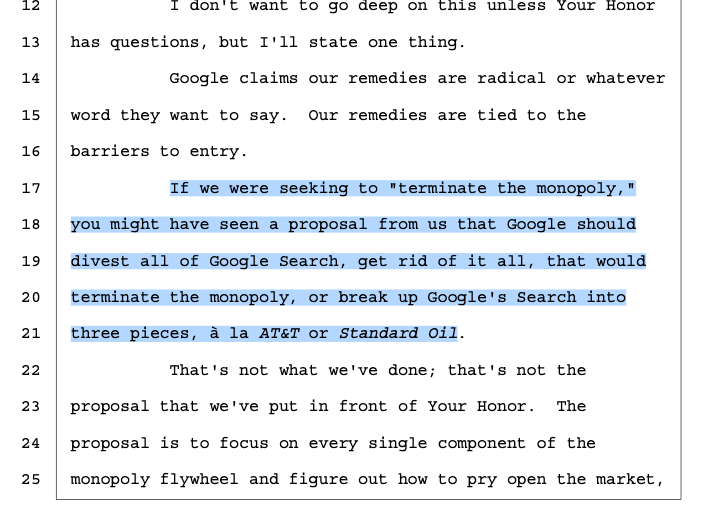

Let’s take a look at the closing arguments in late May in the Google search trial. The Antitrust Division before Judge Amit Mehta made their case to “pry open” the search market, while Google’s head litigator John Schmidtlein of Williams & Connolly attacked the very idea that Google should have any form of penalty. And yet what was striking is how far we’ve strayed from our century long tradition of offering remedies that break apart monopoly power. And that’s not just on Judge Mehta. Schmidtlein spent a good amount of time attacking the government for trying to “terminate” Google’s monopoly, which, you would think, is what a court is obligated to do under antitrust law. Yet rather than say “yes that’s what we’re trying to do,” the Antitrust Division’s top litigator David E. Dahlquist, assured the judge that the government was *not* trying to terminate Google’s monopoly.

Here’s that section of the trial transcript.

Is Dahlquist correct? Well, let’s look at the remedy proposal. The basics of the case are that Google bought up all the shelf space for search engines, aka paid Apple and browsers like Mozilla to be the default search provider instead of any of its rivals. It created Chrome so it could control that channel of distribution, and it bought Android for the same reason. The judge agreed with the government that doing these activities was unlawful monopoly maintenance.

To fix this situation, the DOJ asked to remove the defaults that automatically place Google as the search choice for most browsers, an end to search-related payments, a spinoff of the Chrome browser which was itself a big search access point, as well as regulation of the mobile operating system Android. It also asked for syndication of Google’s search results and data to approved rivals, which is a way of forcing Google to not enjoy the illegal “fruits” of its monopoly by offering rivals some access to the secret sauce.

It’s not a bad remedy, but it is *not* suggesting cloning Google search or breaking it apart into multiple search engines. The remedy, in other words, is not designed to terminate Google’s monopoly, it is structured to eliminate the barriers to entry in search, in the hopes that rivals will come in and challenge Google. That’s sort of, I don’t know, weird. Google just lost, which means that the plaintiff is given greater weight in its remedial proposal and the court is granted with discretion to fashion a remedy that works. Here, we are not just dealing with a one-off bad act, but over a decade of bad behavior in an industry with massive scale and feedback effects. The court should err on the side of a remedy that works, not err on the side of avoiding disruption to the defendant.

We know that breaking up Google search into three firms, as Dahlquist put it, “a la AT&T or Standard Oil,” would end the monopoly, yet that is not on the table. I mean, Schmidtlein, in defending Google, passionately noted the data and syndication remedies would allow Google’s rivals to be able to reverse engineer its systems, and garner the “blood, sweat, and tears” that the search giant had built itself. I felt like I was in la la land listening to that argument. Of course a remedy should allow rivals to copy Google! Its monopoly is illegal! Yet everyone had to dance around this basic point. And in that sense, that right there is Cembalest’s argument in legal form, that the approach by the Antitrust Division in addressing one of the most important monopolies in the world might not work.

That said, the Antitrust Division didn’t just decide to hold its fire for no reason. They are the team that took on Google, bringing the first DOJ monopolization case in 20 years. So what’s the deal? Partly it’s Judge Mehta being afraid of being overturned for being too aggressive, and not fearing being overturned, as he would have in earlier periods of American history, for being insufficiently aggressive. He’s probably paying attention to the Supreme Court, which in a 2020 decision National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, cautioned judges about complex consent decrees. The DOJ had a remedy plank which would have blocked Google from investing in generative AI firms. It withdrew this proposal, likely because it considered it too bold for Judge Mehta. But caution is not the whole story.

The answer is that, though those mid-century cases are still good law, a lot of people with bad ideas won policy debates in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. So Judge Mehta and the DOJ are dealing with another intervening decision, in 2001, by the D.C. Circuit Court, United States vs Microsoft, in which the appeals court overruled a lower court judge who had issued an injunction breaking up the company.

The Microsoft case was of course legendary; it is also controlling precedent in the D.C. district where the Google case is being heard. Both Dalquest and Judge Mehta make it clear how important this decision is for the current Google case. Dalquest joked with the judge that “your copy of Microsoft looks like mine, worn and tabbed and highlighted on every phrase.”

Moreover, and this dynamic cannot be overstated, the entire boomer generation of antitrust practitioners today got their starring roles in the Microsoft case. There are no Standard Oil executives wistfully discussing pipeline wars with the Pennsylvania Railroad anymore. Microsoft is the ONLY major tech monopolization case most of them know; it is what made this generation, that is the case that happened when they were young and vibrant and healthy and watching Friends, and there is no way they would allow fuddy duddy Supreme Court dusty precedent, or the current consolidated economy, to get in the way of bringing back the good old days. So everyone in D.C. who knows anything about antitrust was focused on fitting the existing case into Microsoft precedent, rather than the century-long tradition preceding it.

Antitrust works via analogy, and Microsoft’s behavior looks a lot like Google’s. The argument from the government on Microsoft was that the software giant was using its control of the Windows operating system on personal computers. Since everyone needed access to Windows, it could force original equipment manufacturers and distributors of internet software like AOL to preference its Internet Explorer browser over a rival Netscape Navigator, with a parallel claim involving privileging Microsoft’s tools over Sun’s java programming tools.

It was a “monopoly maintenance” case; Microsoft was seeking to thwart “middleware” like browsers from challenging its Windows monopoly, and thus garnering monopoly profits through illegal maintenance of its market share. In 1998, the judge, Thomas Penfield Jackson, ruled against Microsoft, and ordered the company broken up. But Microsoft appealed, and the D.C. Circuit overturned some of the liability decision. It also remanded the case for a different remedy to a different judge, alleging that Jackson was biased against Microsoft. It was a bold appeals court decision, and one decided unanimously by a number of judges from across the spectrum.

In it, we can see, decades of economic sounding techno-babble take root. “We decide this case against a backdrop of significant debate amongst academics and practitioners over the extent to which ‘old economy’ monopolization doctrines should apply to firms competing in dynamic technological markets characterized by network effects,” wrote the court. Joseph A. Schumpeter made an appearance (“In technologically dynamic markets, however, such entrenchment may be temporary, because innovation may alter the field altogether.”) And the judges cited a litany of Chicago School scholars and current day corporate expert witnesses, such as Dennis W. Carlton, Michael L. Katz & Carl Shapiro, Harold Demsetz, Howard Shelanski, and Richard Schmalensee.

That is what antitrust sounds like with no anti-monopolist voices doing any form of pushback. The D.C. Circuit actually repudiated a century of precedent, noting that “divestiture is a remedy that is imposed only with great caution, in part because its long-term efficacy is rarely certain.” Their only citation was not legal precedent or statute, but a textbook written by two scholars Herb Hovenkamp and Phil Areeda. (You might recognize the name Hovenkamp from a piece I wrote titled “Non-Compete Agreements and the Cult of the Antitrust Bar.”)

The D.C. Circuit Court cited these two men, who rejected Justice Robert Jackson’s decision on how antitrust remedies can be applied creatively to address the fruits of the monopoly. A judge couldn’t just order a break-up, everyone seemed aghast at the very notion. “Structural relief,” wrote the D.C. Circuit Court, “which is ‘designed to eliminate the monopoly altogether ... require [s] a clearer indication of a significant causal connection between the conduct and creation or maintenance of the market power.’” This argument flipped 100 years of remedy on its head, and was entirely vibes from two law professors who supported corporate concentration. This part wasn’t binding, it’s known as “dicta,” aka judicial vibes, but it still haunts the case law today.

At the time, few noticed the shift in doctrine on remedy. There was no anti-monopoly movement to point it out, but more importantly, the Microsoft case was the last monopolization claim brought by the DOJ until Google. By 2024, when Judge Mehta found Google liable for monopolization, no one had dealt with the problem of remedies for 25 years. And then, after Google lost, everyone broke out their Microsoft appeals court decision, assuming that the circuit court was faithfully following Supreme Court precedent, when it was not. In that 2001 Microsoft decision, the last successful antitrust case, we can also see the legal roots of our consolidated economy.

Ok, so that’s where we are. But one of the remarkable aspects of the current moment is how much the conventional wisdom has changed. A few years ago, it would have been unthinkable to see Google as an illegal monopolist, let alone with three judges saying so. And now that Judge Mehta has dubbed the company’s conduct unlawful, it seems weird to offer such mild remedies.

For decades, enforcers refrained from bringing monopolization cases because of a perception that bold cases are not winnable. Now, we are seeing wins all over the place because enforcers and plaintiffs had the audacity to try. The same is true for remedies. The law is actually quite expansive and permissive when it comes to fashioning big and bold structural remedies. Sometimes you just have to ask.

Moreover, we are not in the 1990s, today and everyone can see that dominant firms are dangerous. It’s only a matter of time before we make the obvious conclusion that courts must, if they find violations of monopolization law, oversee a termination of said monopoly. If they don’t, well, then we’ll have a few big firms, and nothing but a smoking crater where the economy used to be.

Thanks for reading!

And please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. And consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member.

cheers,

Matt Stoller

.png)