Much of our current discussion about consciousness has a singular fatal flaw. It’s a mistake built into the very foundations of how we view science — and how science itself is perceived and conducted across disciplines, including today’s hype around artificial intelligence.

What most popular attempts to explain consciousness miss is that no scientific explanations of any kind can be possible without accounting for something that is even more fundamental than the most powerful theories about the physical world: our experience.

Since the birth of modern science more than 400 years ago, philosophers have debated the fundamental nature of reality and the fundamental nature of consciousness. This debate became defined by two opposing poles: physicalism and idealism.

For physicalists, only the material that makes up physical reality is of consequence. To them, consciousness must be reducible to the matter and electromagnetic fields in the brain. For idealists, however, only the mind is real. Reality is built from the realm of ideas or, to put it another way, a pure universal essence of mind (the philosopher Hegel called it “Absolute Spirit”).

Physicists like me are trained to think of the world in terms of its physical representations: matter, energy, space and time. So it’s no surprise that we physicists tend to start off as physicalists, who approach the question of consciousness by inquiring about the physical mechanics that give rise to it, beginning with subatomic particles and then ascending the chain of sciences — chemistry, biology, neuroscience — to eventually focus in on the physical mechanics occurring in the neurons that must generate consciousness (or so the story goes).

This kind of “bottom-up” scientific approach has contributed to modern science’s success, and it is also why physicalism has become so compelling for most scientists and philosophers. This approach, however, has not worked for consciousness. Trying to account for how our lived experience emerges from matter has proven so difficult that philosopher David Chalmers famously referred to it as “the hard problem of consciousness.”

We use the term consciousness to describe our vividly intimate lives — “what it is like” to exist. But experience, which encapsulates our consciousness, thereby cuts more effectively to the core of our reality. An achingly beautiful red sunset, a crisp bite of an autumn Honeycrisp apple; according to the dominant scientific way of thinking, these are phantoms.

Philosophically speaking, from this physics-first view, all experiences are epiphenomena that are unimportant and surface-level. Neurobiologists might fret over how experience appears or works, but ultimately reality is about quarks, electrons, magnetic fields, gravity and so on — matter and energy moving through space and time. Today’s dominant scientific view is blind to the true nature of experience, and this is costing us dearly.

The Blind Spot

The optic nerve lies at the back of the human eye, connected to the retina, which is made up of receptors sensitive to incoming light. The nerve’s job is to transmit visual input gathered by those receptors to the brain. But the optic nerve’s location atop a tiny portion of the retina also means there is a blind spot in our vision, a region in the visual field that is literally unseen.

In science, that blind spot is experience.

Experience is intimate — a continuous, ongoing background for all that happens. It is the fundamental starting point below all thoughts, concepts, ideas and feelings. The philosopher William James used the term “direct experience.” Others have used words like “presence” or “being.” Philosopher Edmund Husserl spoke of the “Lebenswelt” or life-world to highlight the irreducible totality of our “already being in a living world” before we ask any questions about it.

From this perspective, experience is a holism; it can’t be pulled apart into smaller units. It is also a precondition for science: To even begin to develop a theory of consciousness requires being already embedded in the richness of experience. But dealing with this has been difficult for the philosophies that guide science as it’s currently configured.

In many ways, experience landed in science’s blind spot by design. As the methodologies of modern science were being established from the 16th through the 19th centuries, a central goal was to set aside personal, or subjective, elements. What the early architects of the scientific method, such as Francis Bacon, sought to do was break down the elements of experience into aspects that remain unchanged from person to person, or what the philosopher Michel Bitbol calls the “structural invariants of experience.” Identifying these elements, which became the basis for making measurements, was the first step in our scientific interrogations of nature.

“An achingly beautiful red sunset, a crisp bite of an autumn Honeycrisp apple; according to the dominant scientific way of thinking, these are phantoms.”

In this way, over time, scientists began to imagine a perspective-less perspective, a supposed God’s-eye view of the universe — free of any human bias. The philosopher Thomas Nagel calls this the “view from nowhere.” And this philosophical position eventually became synonymous with mainstream science itself.

The development of the thermometer, and from it the science of thermodynamics, offers a notable example of our scientific culture’s blind spot. In it, we can see how those unchanging elements of experience are extracted and then, in time, misconstrued as a false perspective-less perspective.

The embodied feeling of being hot or cold is a basic example of direct experience. But developing a measurable scale of this experience for future scientific inquiry took centuries of work. Much of this story played out in what we now call laboratories, where those elements of experience could be isolated and probed. First, hot and cold needed to become correlated with something like the level of alcohol or mercury in a graduated tube. This was the invention of thermometry. Once a way to measure degrees was established, those degrees could then be used to investigate other focal points of experience, like the boiling point of water. A mathematically formulated theory of thermodynamics was then slowly developed, describing the relationship between temperature and heat flow. Later, higher levels of abstraction came as the random motions of unseen atoms — studied via the new field of statistical mechanics — were recognized as the true nature of heat. In this way, more phenomena studied in labs became describable in ever more precise terms. Along with those new, precise descriptions came new, powerful capacities to control the world via technologies like heat engines or refrigeration.

As this upward spiral of abstraction was traversed, something, however, was lost. In what Husserl called the “surreptitious substitution,” abstractions like thermometric degrees were treated as more real than the experience they imparted. Eventually, the first-person, embodied experience of being hot or feeling cold was pushed aside as a phantom epiphenomenon, while abstracted quantities like temperature, enthalpy, Gibbs potentials and phase space became more fundamental and more real. This amnesia of experience is science’s blind spot.

A New Key

The poles of physicalism and idealism are, however, not science’s only philosophical options. There are other alternatives, and they can be used to ground a scientific recognition of experience.

Alfred North Whitehead, a renowned 20th-century mathematician who co-authored the “Principia Mathematica” with Bertrand Russell, warned of the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness” in which the abstractions of mathematical physics are taken to be more real than nature as it’s experienced. He also argued against the “bifurcation of nature,” where a sunset’s amber hues are considered a secondary reality, fundamentally reducible to the primary reality of electromagnetic waves and the motion of atoms. In his “process philosophy,” experience was fundamental.

Husserl, who was trained as a mathematician, founded phenomenology — an influential philosophical approach that took experience, rather than formal systems of reason or logic, as its starting point and raison d’être. This is the origin of Husserl’s use of the concatenated term “life-world.” For phenomenology, there are no atoms of experience from which it could be built up. Instead, it is a study of lived human experience, in its all-encompassing immediacy. This requires trying to understand how humans encounter and make sense of the world they are enmeshed in. Husserl and others who followed, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, understood that explaining consciousness with the physicalist’s God’s-eye third-person perspective was impossible.

Whitehead and Husserl represent themes in philosophy that lie outside the usual physicalist-idealist split and demonstrate that there are other principled paths to engaging with questions about experience. We must also note that other civilizations have given considerable thought to these questions. Classical philosophers from India, like Nagarjuna (approximately 150 to 250 C.E.), attempted to systematically approach the question of experience without defaulting to third-person views. In stature and capabilities, these philosophers were the equivalent of Plato, Aristotle and St. Augustine, and they took the immediacy of experience seriously. Today, their work is beginning to be seriously considered in domains as varied as physics and cognitive science.

So, how might these varied philosophical perspectives inform a new science of experience and consciousness? The first step is to push back on the machine metaphor, which is the dominant blind spot approach to all life. The reductive physicalism of this approach views organisms as nothing more than complicated machines composed of biomolecules engaged in biomolecular shenanigans. From this standpoint, you are nothing more than a computer made of meat living in a robot body made of muscle and bone. To be clear, there is no doubt that understanding the mechanisms associated with biomolecular processes, the functioning of the heart and the firing of neurons can be incredibly useful. But the problem with thinking of organisms as machines is that we overlook what is most important about them: their organization.

A machine engineered for a designated purpose is utterly and fundamentally unlike an organism. What makes living organisms so different from the other systems physicists study is that they each form a self-consistent unity, a holism. Cells are thermodynamically open, meaning matter and energy are constantly flowing through them. Excluding its DNA, a cell’s atoms today are not the same ones that may make it up a week from now. So a cell’s essence is not its specific atoms. Instead, how a cell is organized defines its true nature.

“Today’s dominant scientific view is blind to the true nature of experience, and this is costing us dearly.”

In 1790, the philosopher Immanuel Kant invented the term “self-organized” to describe what made the organization of living things distinct from everything else. In the 1970s, neuroscientists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela took Kant’s idea further, coining the term “autopoiesis” to help describe the unity or holism of an organism’s organization.

To be autopoietic means to be self-creating and self-maintaining. As of today, only living systems can claim the mantle of autopoiesis. Consider the cell membrane. By allowing some molecules in and keeping others out, the membrane is essential for cellular metabolism. But the membrane is also a product of metabolism. Molecules allowed in are used to build the membrane wall and regulate its activities. In this way, the network of processes that allow the cell to be alive is organizationally closed because the chain of cause and effect that keeps the cell going forms a closed cycle, a holism, a unity. This autopoietic, organizational closure is what separates living systems from machines in the most essential way.

Ideas such as autopoiesis and organizational closure have also found their way into the study of the mind, cognition and consciousness. A particularly promising research program is the enactive approach, first described by Varela, Eleanor Rosch and Evan Thompson in “The Embodied Mind.” From this scientific perspective, consciousness is something you do, not something you have. Experience and consciousness are performed. That means organisms are not machines but autonomous agents that actively create or “enact” their own experience and the environment they inhabit through those actions. Organisms are inseparable from their life-worlds, and these life-worlds are shaped by the organism, its actions and interactions.

Embodiment is another critical idea in the enactive approach. Embodiment recognizes that cognition cannot be separated from the body and its sensorimotor capacities. How we move and interact with the world directly shapes what and how we both perceive and understand. Finally, the enactive approach also emphasizes the idea of embeddedness. Cognitive processes are not isolated brain functions but are situated within and depend upon the organism’s physical and social environment. Cognition and consciousness are thereby sense-making; organisms are engaged in an active, ongoing process to establish meaning and relevance as they interact with the world to maintain their viability.

The focus on the machine metaphor and the lack of focus on the notion of embodiment are both principles evident in the proclamations by some scientists that general artificial intelligence is here, or around the corner. The technologist Blaise Agüera y Arcas argues that AI models might lack “bodies or life stories, kinship or long-term attachments,” but that these questions are “irrelevant … to questions of capability, like those about intelligence and understanding.” This is not only misguided it also poses real dangers as these technologies are deployed across society.

The problem is, once again, surreptitious substitution. Intelligence is mistaken as mere computation. But this assumption undermines the centrality of experience, as philosopher Shannon Vallor has argued. Once we fall into this kind of blind spot, we open ourselves to building a world where our deepest connections and feelings of aliveness are flattened and devalued; pain and love are reduced to mere computational mechanisms viewable from an illusory and dead third-person perspective.

A New Vision Of Nature

The difference between the enactive approach to cognition and consciousness and the reductive view of physicalism could not be more stark. The latter focuses on a physical object, in this case the brain, asking how the movements of atoms and molecules within it create a property called consciousness. This view assumes that a third-person objective view of the world is possible and that the brain’s job is to provide the best representation of this world.

The enactive approach and similar phenomenologically grounded perspectives, however, don’t separate the brain from the body. That is because brains are not separate things. Like the unity of cell membranes and the cell, brains are part of the organizational unity of organisms with brains. Organisms with brains, therefore, aren’t just representing the world around them; they are co-creating it.

“Intelligence is mistaken as mere computation. But this assumption undermines the centrality of experience.”

To be clear, there is, of course, a world without us. To claim otherwise would be solipsistic nonsense. But that world without us is not our world. It’s not the one we experience and from which we begin our scientific investigations. Therefore, this third-person perspective of a world without us and our experience, is nothing more than a sophisticated kind of fantasy.

The role of other living beings also distinguishes the blind spot view from those which make experience central. Whereas physicalists have traditionally thought of brains and their conscious states as reproducible anywhere, even in isolation (see: the famous brain-in-a-vat idea or “The Matrix”), the life-world of experience is a world of others. The structure of my first-person experience cannot be described without you, without others, because life always occurs in communities. In this way, the entire planetary history of life becomes implicated within individual experience. To be alive and have experience is to constantly make sense of environments through our interactions with them. We, as conscious organisms, never do this alone.

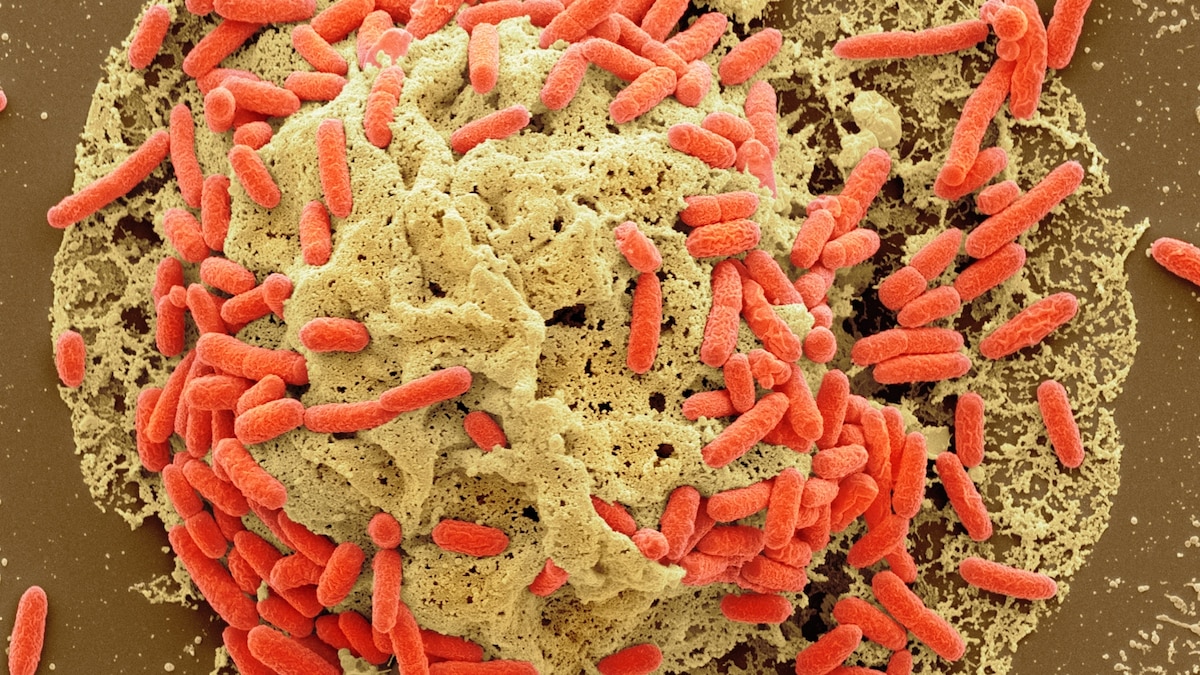

Recognizing that any account of experience requires the presence of others and our embodied interaction with them takes us beyond the machine metaphor in another essential way. Rather than a pure focus on consciousness, research utilizing the enactive view delves into the deeper question of sentience — the basic feeling of being alive. Researchers like Michael Levin have noted the mounting evidence that communities of microbes and even individual single-celled organisms may possess some kind of sentience and display rudimentary cognitive functions. Of course, no one is arguing they have the kind of consciousness humans possess. But if sentience is fundamental to life, then experience may be life’s fundamental essence. To be alive is to be a locus of experience, a mutually arising autonomous agent and its co-created environment or life-world.

A New Physics Of Life & A New Life For Physics

Once we recognize that the third-person scientific perspective is an incredibly useful fiction, our view of nature changes as well. Whitehead said the job of philosophy was to explain the abstract, not the concrete. Experience is the concrete, and we must take it as a given. From that embodied perspective —the only perspective we ever get — we can never separate experience from nature. We can never tell our deepest stories about the universe without including ourselves in it.

It’s worth noting that this seems to be the message that quantum mechanics — the greatest triumph in physics — has been trying to tell us for over a century. The stubborn insistence of quantum theory that measurements and the agents making them are central to physics can be seen as a recognition of exactly this experience-first unity of us with nature.

From this new perspective comes a new coda for physics and all of science. We seek not to embed our experience in physics but to embed physics into our experience. Our job in understanding consciousness and experience is not to explain it away via the formal systems of mathematical physics. Instead, we must understand how the profound and powerful regularities that physics (and all science) reveal manifest themselves as an integral part of experience. We don’t seek explanations that eliminate experience in favor of abstractions but rather, we must account for the power of abstractions in the structures of experience.

There is new and exciting science to be done here. My colleagues and I are exploring a view of the physics of life that recognizes organisms as the only physical system that uses information; for example, by storing, copying, transmitting and processing it. Rather than reducing life to “nothing but” a computer, this view emphasizes the semantic nature of life’s information use. The project aims to understand the autopoietic, organizationally closed information architecture of organisms. Instead of explaining away the sentience or consciousness of autonomous agents, this work might give us an empirically validated perspective on the specific structures and processes occurring within experience. These kinds of investigations can also go beyond conscious organisms like us and may help understand how experience, or something like it, can appear in other forms, including silicon. If nothing else, they will help us push past the hype surrounding our current discussions of AI to see the real issues surrounding what makes something intelligent.

This work is merely a first attempt at bringing a new vision of nature into view. What matters most is it’s a life-first, experience-first perspective. We live in a moment when the fruits of science have contributed to both the thriving and the potential collapse of our collective project of civilization.

Moving beyond consciousness as a mechanism in the dead physical world toward a view of lived experience as embedded and embodied in a living world is essential for at least two reasons. It may be the fundamental reframing required to make scientific progress on a range of issues, from the interpretation of quantum mechanics to the understanding of cognition and consciousness.

Recognizing the primacy of experience also forces us to understand that all our scientific stories — and the technologies we build from them — must always include us and our place within the tapestries of life. Recognizing there is no such thing as an external view has consequences for how we think about urgent questions like climate change and AI. In this way, the new vision of nature that comes from an experience-centric perspective can help us take the next steps necessary for human flourishing. That goal, after all, was also one of the primary reasons we invented science in the first place.

.png)