I’m a philosopher who uses AI a lot. But I’d never been tempted to write about AI and consciousness until last week, when I started watching ‘prompt theory’ videos on Twitter. You know what I mean: those super-high-quality short films, made using AI, all differently posing the dystopian question, “What if the people in AI videos were real people, aware of themselves and their surroundings, gradually coming to the conclusion that their fate was to live at the whim of our typed prompts?”.

Heavy stuff. One of these videos depicts its stars as actors, forced to perform everything from love to death in eight-second bursts, as many times as we humans demand. There’s a woman in period costume pleading not to have her head chopped off again. There’s a couple admitting to each other that the romantic scene they’d just finished filming was the greatest experience they’d ever known. Another video shows a serious-looking guy telling his friend that if he believes in prompt theory, then that’s because ‘the prompter’ wants him to. That one, in particular, changed my mind.

Ok, it didn’t persuade me that AI is conscious! And it certainly didn’t persuade me that AI is struggling with the truths of a human-directed kind of determinism. None of these videos changed my view that talking about AI in such ways is to misrepresent the kind of thing it is. They did make me realise, however, that now is exactly the time to be writing about the confluence of AI and consciousness — because they made me realise that the Age of AI is the Age of Philosophy.

To be fair, this wasn’t a total change of mind. I already thought it highly likely that doing philosophy would remain a relatively safe intellectual career option in the face of upcoming AI-related labour-market change. I’ll return to this idea in the second half of this piece, alongside setting out my thoughts on the kind of thing AI is, when I argue that the Age of AI is the Age of Philosophy because it’s a great time to be a human philosopher. First, however, I’m going to argue that this is the Age of Philosophy, for a different reason.

The everyday philosophical impact of AI

My immediate response to watching those prompt theory videos was to message a friend saying, “Any second now the hyper-detailed nuances between all the different theories of determinism go mainstream!”. I didn't mean by this that I assumed every viewer would immediately see that the substance of these videos is grounded in the substance of complex philosophical theory. It was more that I thought these videos exemplified the way in which engaging with the idea of AI offers a route into deep philosophical thinking. You can see this in the determinism discussion that’s prefigured by the suggestion that the promptees are prompted into believing in prompt theory. And you can see it as soon as you start thinking through the complexities of the idea that each of the ‘AI actor’ characters has their own prompt-driven life.

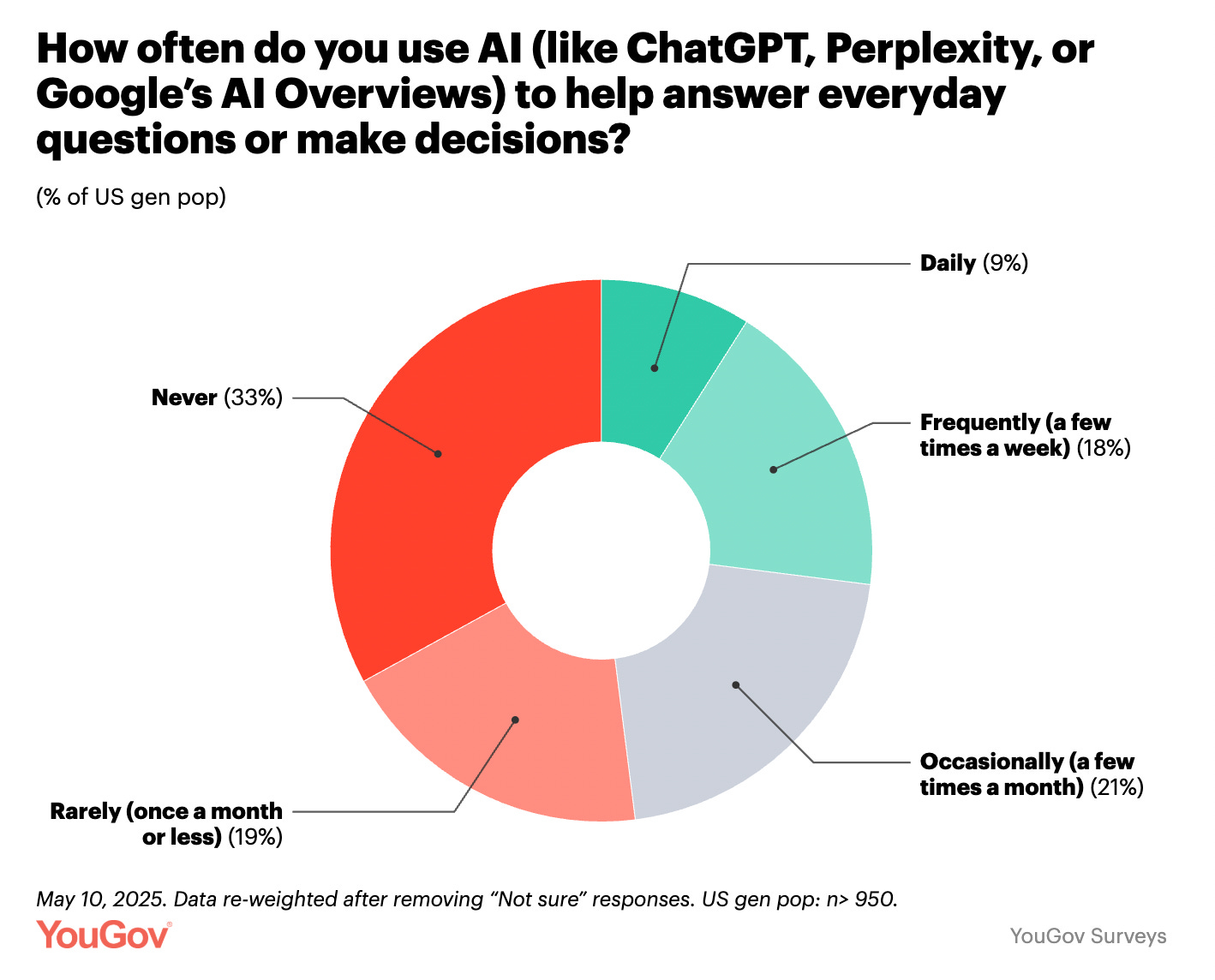

Perhaps you think I’m being patronising. Perhaps you think rigorous discussion about free will and consciousness has been mainstream since The Matrix. Well, you’re reading this piece on my unashamedly philosophy-heavy Substack, so perhaps your thoughts on The Matrix aren't representative of the general public! Beyond that, the silent role we humans play as prompters in these videos remind us that since The Matrix was released, we’ve gone far beyond engaging with these ideas as storylines in sci-fi movies. We’re living them! This is an age in which we speak with machines. Recent polling suggests that almost a tenth of Americans use AI every day. Every day! It’s an age in which it’s normal to hear people talk about machines ‘thinking’ and ‘reasoning’. AI has brought philosophy to the forefront of our lives, in a totally new way.

What I really mean, of course, is that AI has brought a foundational subset of philosophy to the forefront of our lives — specifically, philosophy of mind and metaphysics. These are the philosophical domains that focus, respectively, on the relation between the mind and the body, and on what kinds of things exist in the world. At heart, philosophy of mind is focused on questions like how it is we humans can be both ‘thinking things’ and ‘physical things’. And metaphysics is focused on “chart[ing] the possibilities of real existence”. In many ways, these are the deepest and most difficult domains of philosophy.

Their depth is shown by the way you can’t get off the ground in other philosophical domains without making some prior commitments in philosophy of mind and metaphysics. I mean, as a political philosopher, how can I respond to arguments about whether prison is permissible, if I don’t accept that other people exist? How can I talk seriously about right and wrong, if I don’t accept that humans and tigers have minds whereas rocks and gravity don’t? And how can I go about considering which of my beliefs count as knowledge, if I don’t accept that I’m the kind of thing that can have beliefs?

Moreover, all of us humans have to accept premises from these foundational philosophical domains to be able to get on with our lives. Indeed, a standard objection levelled at the philosophers of mind who claim they don’t believe in free will is that denying free will is in tension with their everyday behaviours. Please find me a free-will denier who doesn’t get angry at the thug beating up their elderly neighbour! Of course, there are cogent responses to this objection. But the common-sense position on free will — which is, of course, that we have it — is default largely because thinking otherwise requires effort of the kind most people don’t apply to such matters. Until now! Until we started living in the Age of Philosophy.

Previous ages of philosophy

But wait a second, you say. Surely this isn't the first Age of Philosophy, is it? Isn’t there an analogous argument, for instance, that times of war can count as ages of moral and political philosophy? After all, those are times in which standard views about moral and legal obligation are put under pressure, and the concept of justice is tested to the extreme. Times in which ordinary people find themselves having to make urgent choices about who they should protect from threat, and re-evaluating previously hard limits on harming one another.

Ok, I’m happy to accept there have been previous ages of philosophy. Indeed, it’s relevant for the argument I’m going to make in the second half of this piece that World War Two wasn’t just a time in which moral and political questions came newly alive for non-philosophers. WW2 spawned a revolutionary set of moral and political philosophers! John Rawls, who kick-started political philosophy afresh in the second half of the twentieth century, was heavily influenced by his wartime experiences: not only to become a philosopher rather than a priest, but also to spend his skills on questions of justice. And two recent books advance the argument that a group of female moral philosophers — Philippa Foot, Elizabeth Anscombe, Iris Murdoch, and Mary Midgley — were influenced by their wartime experiences to move beyond dominant approaches in moral philosophy. This context might make you ask: which of the teenagers watching prompt theory videos today will become the future Rawls and Foot of foundational philosophy?

All that said, it’s hardly surprising there have been ages of moral and political philosophy. These are philosophical domains involving everyday concepts, like good and bad, and rights and obligations, and consent and authority. Almost everyone has some kind of handle on these concepts, whether or not they refer to them by the same names — including people who’ve never begun to address more advanced philosophical concerns like the edges of these concepts, or their interrelation or grounding. So, while I’m happy to accept that times of war heighten public awareness of political and moral philosophical matters, there’s an everyday level on which awareness of the content of those domains can typically be found.

In contrast, consciousness and free will are not everyday concepts. Sure, many people have heard of them. But most won’t hold them anywhere near clear in their minds. Indeed, there are levels on which such a statement would only be parsed by people who've spent time thinking hard about these concepts! So yes, every so often, perhaps a sweet interaction with a cat makes a non-philosopher wonder whether animals have deeper interiority than they’d assumed. Or a sense of déjà vu makes them question their freedom to direct their own life. But most non-philosophers will never have had cause to think about these important concepts in anywhere near the enriching depth we all deserve to think about them. It’s the same with the core concepts of metaphysics — concepts like possibility and personal identity. And with metaphysics, you definitely don’t have to get on to the advanced stage to get beyond the everyday: many metaphysical concepts are advanced in themselves. They're weird and slippery and distant, even though they're also basic and strong and crucial.

My hope is that new awareness of some of these concepts, arising from everyday interactions with AI, and reflections on those interactions, will improve foundational philosophical thinking, on the general level. This will take time. It's taking a while, for instance, for society to get past the idea that it's ok to assume that AI could be conscious simply because AI can tell us it’s conscious. If that were sufficient, then philosophers wouldn’t have spent so long getting hung up about whether other humans were conscious! I mean, in the same way that just because I perceive you standing there in front of me doesn’t mean you definitely exist, it’s also the case that you telling me you’re conscious simply isn’t enough, either. Yet this is the superficial level that many AI commentators have been stuck at for some time: “But, but, it says I’ve hurt its feelings…” My guess is that a non-philosopher who'd watched and thought about the prompt theory videos would be better placed — all other things being equal — to pose good objections to that kind of overly-simplistic position than one who hadn’t.

So, my first argument is that the Age of AI is the Age of Philosophy because AI brings foundational philosophy into everyday life for the first time. This is in large part because we can converse with AI, even though it's categorically different from us. AI can now do many of the things we can do — and increasingly, do them better than us — yet it has neither a brain nor a mind. This takes me to my second argument.

The human advantage at doing philosophy

My second argument that the Age of AI is the Age of Philosophy hinges on the idea that now is a great time to be a human philosopher. That is, having attempted to persuade you that there are philosophical benefits for everyone to gain from interacting with AI, I’m now going to argue that becoming a philosopher is a smart career option for particularly philosophically-minded humans.

My argument isn’t going to involve making predictions about what it’ll look like to be a human philosopher over the coming decades, however. I won’t use this opportunity to weigh in on the debate about whether intellectuals will continue to work in university departments and publish in specialist journals. Although, my guess and hope is that as universities and journals lose their monopoly status to AI, and as philosophical thinking becomes more mainstream, philosophy will become more decentralised as a profession. Rather than trying to look into the future, however, I’m going to focus on some natural advantages that humans have over AI when doing philosophy.

First, I want to be clear that I do think AI is capable of producing good philosophical writing. I wrote a piece here, back in December, about the vast improvements I’d seen with ChatGPT, to this end. I wrote about finding it astonishing that I could talk good philosophy with a text box. I still find that astonishing and hope I always will. I faced pushback from other philosophers, however, about the claim I made that o1pro, then the best GPT model, could produce PhD-level work on any philosophical topic. Those people clearly think a philosophy PhD represents a much higher bar than I do! Don’t get me wrong, most of the smartest people I know have philosophy PhDs. But you only need to meet a few of the many non-smart PhD philosophers to know this isn’t a particularly impressive baseline to set for AI. Knowing that and admitting it are different things, however.

Now, what I was mostly talking about in that piece was philosophical output. I was discussing the extent to which I found o1pro’s answers, in the regular conversations I had with it, satisfying enough to measure up to a human philosophical interlocutor. I’m lucky to have some great human philosophical interlocutors, and it remains the case that I’d always far rather speak with them about philosophy than with AI. But, as I wrote in December, when I want to talk about Quine at 2am, then the latest GPT model will definitely suffice.

Today, however, I’m going to argue that while the best LLMs can produce philosophical writing that’s satisfying for human philosophers to engage with, there are some crucial parts of ‘doing philosophy’ at which humans have a strong natural advantage. I’ll approach this by discussing four ways in which humans are relevantly different from AI. Then finally, I’ll make the more extreme suggestion that AI’s lack of these qualities means that it’s never really doing philosophy at all, but only simulating it.

Four differences between humans and AI

An obvious starting point when thinking about the differences between humans and AI is consciousness. As above, there’s a long debate in philosophy about how you could know whether another living thing has the same kind of interiority as you: a cat, an ape, even another human. Is this other creature able to go beyond eating the banana, and have the experience of doing so? Do they taste the banana while eating it? Can they reflect on such experiences? Contemporary philosophers often address this phenomenological notion of consciousness in terms of ‘what-it’s-like-ness’, influenced by Thomas Nagel’s famous paper, What Is It Like to Be a Bat?. On this approach, something is only conscious if there is ‘something it’s like to be’ it.

One route into concluding that AI lacks consciousness, therefore, is first to argue that only living things can have phenomenological experience, and then to argue that AI is not alive. I’m not going to take that approach, however. This is partly because, as I discussed here the other day, it’s really hard to come up with a satisfactory definition of ‘being alive’. But also because you and I both know that AI is not alive. I mean, I may not be able to satisfactorily define ‘being alive’, but if it turns out that AI is indeed alive, then the word ‘alive’ clearly picks out a concept that’s vastly different from the ways we standardly use it.

Nonetheless, rather than assuming you agree with me that AI is not alive, I’m going to try to convince you that AI lacks a quality that is necessary both to being alive and being conscious: particularity. Specifically, I’m going to argue that we don’t even get on to asking, “Is there something it's like to be AI?”, if AI isn’t an individuated thing that persists across time.

First, it seems clear that AI — in the sense of your abstract LLM conversant — cannot persist across time, because its ‘existence’ starts afresh with every response, or maybe even every word, it produces. Moreover, the ‘it’ here isn’t a specific entity that's engaging with you. Not even for a split-second! Rather, ‘it’ is an instance of the functionality of a specifically-‘weighted’ type of system. This is how the same AI model can hold different conversations with so many of us at the same time. Acknowledging this lack of particularity can help to explain why it feels funny when people talk about ‘AIs’ (in the plural) to refer to different AI models or brands. But also why it feels funny when people talk about ‘AI’ (in the singular) to refer to a wide-ranging set of models and brands. Maybe you felt this when I wrote, “Is there something it's like to be AI?” rather than, “Is there something it's like to be an AI?”.

Whereas, we’re used to the things we interact with being physical things with obvious particularity. Especially the things we converse with! And we’re used to this including — by necessity — the things we interact with that are parts of groups. We wouldn’t be able to talk about ‘what it’s like to be human’, if we couldn't priorly talk about ‘what it’s like to be a particular human’. This is because talking about ‘what it’s like to be human’ is talking about what it’s like to be an individual who's part of the group that’s humankind. Whether it’s a person or an animal you’re speaking to, or a plant or a rock you’re holding in your hand, you can count these things as individuated things: you can pick them out. And even when the things you interact with have blurrier edges than humans or rocks — things like seas and parks and heaps of sand — each of them, in its complicated compositeness, still counts as separate.

Consciousness, understood in the phenomenological sense of ‘what-it’s-like-ness’, trades on subjectivity — both in this sense of 'being individuated', and in the sense of 'being a subject of experience’. And while it’s hard to conclude that something else, aside from you, is or isn't a subject of experience, it’s typically not too hard to conclude that something else is or isn't individuated.

The most obvious objection to the idea that AI isn't the kind of individuated thing that persists across time relates to the introduction of the AI ‘memory’ function. That is, you might see as decisive here the way in which, nowadays, when you hold a conversation with certain AI models — o3, for instance — the responses you receive bear reference to previous things you’ve discussed together. This is because the content of your conversations is now stored in a database, which the model has the functionality to access, “via an external retrieval step”.

What makes this ‘memory’ objection seem particularly strong, I think, is that memory is often appealed to in arguments for human personal identity. That is, Lockean-type personal identity theorists, for instance, argue that a thick conception of memory (simply put, my awareness of my previous self-awareness) can be used to conclude that my personhood persists across time. And that even if I don’t remember what it was like to be two-year-old Rebecca, I can still remember what it was like to be thirty-year-old Rebecca, when I remembered what it was like to be twenty-year-old Rebecca, and so on, in a neat little backwards chain.

Of course, this is an over-simplification of the details and developments of Lockean-type personal identity arguments. But it can help to show how the ‘memory’ objection to my particularity argument isn’t as strong as it might seem. This is because the Lockean-type personal identity arguments depend on a conception of memory that goes far beyond o3’s capacity to access the externally-stored content of conversations. Indeed, this Lockean-type conception of memory has self-awareness baked into it! So, while the ‘backward chain of human memories’ idea might seem helpful for dealing with the fact that o3 doesn’t hold all of ‘its’ memories at the same time, the problem remains that these ‘memories' are not ‘its memories', in the sense that they aren’t (and never were) the reflections of a self-aware thing. In other words, sure, if you can persuade me that o3’s memory function is proof of its consciousness, then you win the overall argument. But until you can do that, you don’t defeat the sub-argument I'm making, which is that AI doesn't have particularity.

I should note at this point that there's another notion of consciousness, which is often alluded to in discussions of AI. This notion tracks functions rather than feelings. Some people suggest, for instance, that AI would count as conscious if it could produce the same kind of output as a conscious person, or behave in other similar ways. One problem with this approach, however, is that it tends toward circularity: ‘Hey, this thing behaves as if it’s conscious, so that’s enough to be conscious. Oh wait! It’s behaving as if it’s conscious, therefore it must be.’ More importantly, however, the ‘what-it’s-like-ness’ really matters, particularly for our current purposes. We can’t just bypass it. This is because the kind of subjectivity we have as humans — as particular individuals who can experience and reflect on what it’s like to exist in the world — is highly advantageous to being a successful philosopher. I mean ‘successful’ here both in the sense of being in demand by readers of philosophy, and in the sense of producing good philosophy.

Think of the way in which beginner philosophy essays tend to be very descriptive. They might take the following kind of path: ‘Plato says this about x; Nietzsche says this about x; Russell says this about x; so now we know some things about x’. I don’t mean to denigrate these efforts. They’re crucial to building philosophical awareness and skill, and typically involve some analysis and evaluation as well as pure description. But doing philosophy at a more serious level involves making bigger personal commitments, and taking bigger personal risks: it involves making your own arguments. To do this, you have to be able to do things like committing to premises for reasons, becoming convinced, and being open to changing your mind.

Humans can do these things because we are free agents: because we are able, at least some of the time, to make reasoned decisions about how to act, and to act on those decisions. That is, as a human, you have a special kind of reflective and causal capacity to make and act on your own reasoned decisions. That this involves introspection and intention, both of which depend on subjectivity, helps to explain why the term ‘reasoning’ is often put in inverted commas when used to refer to AI activity. On a functionalist approach, where what matters is process and output, there’s a sense in which AI does ‘reason’ through problems, in terms of having the capacity to weigh and select options. There’s much debate, of course, about how exactly this happens! But unless AI has subjectivity, then its ‘reasoning' does not match the deeper kind of reasoning carried out by a free agent.

Rather, to use a standard philosopher analogy, AI reasoning is ’zombie reasoning’. That is, in the same way you can imagine a ‘zombie you’, who looks just like you, and goes about your life doing the things you do, but has no interiority, you can think of ‘zombie reasoning’ as reflecting the outputs, and even some of the processes, of the reasoning of a free agent — but also without recourse to interiority. It’s the same with AI ‘deciding’ and ‘thinking’ and ‘knowing’, and some of the less introspective concepts like ‘acting’. The reason it makes sense to put these words in inverted commas, that is, is because the AI versions of these activities are shadow versions of what we humans are capable of. Of course, it’s hard for us to conceive what it would be like to do these things on the shadow level, but AI has it much harder, because it cannot conceive at all.

An obvious objection, however, against the idea that humans possess this natural advantage over AI comes in the form of skepticism about free will. This objection doesn’t provide support for the idea that AI can move beyond ‘zombie reasoning’, but it does make us question whether we humans have the agency required to reason fully, ourselves. In other words, if all of our actions were predetermined, then it couldn’t be the case that we were ever fully making and acting on our own reasoned decisions, in the sense required to be free agents, could it?

For current purposes, however, I don’t have to persuade you that we are free agents. This is because even if we don’t have power over our reasoning and acting, at least we experience those things happening. We know what it feels like to deliberate, to decide, to know, to act. So sure, if we don’t have free will, then we aren’t responsible for the consequences of the reasoning and acting we experience. But that wouldn’t mean our reasoning was full-on ‘zombie reasoning’, because it wouldn’t mean it lacked interiority — so we’d still remain in a stronger position than AI to do philosophy. Of course, the obvious follow-on objection takes the form of asking whether we can ‘do’ anything at all, including philosophy, if we don’t have free will. But I’ll return to that in a moment, when I make a distinction between doing philosophy and simulating doing philosophy. For now, my previous response still stands: at least we would experience it.

AI’s lack of phenomenological experience is most philosophically limiting in relation to moral matters. Here, AI isn’t just at a disadvantage because it cannot reason for itself — or even simply experience what it feels like to reason — it also has no physicality. AI’s abstract nature means that it lacks the specific kind of insight necessary to doing much moral philosophy: the insight that comes from being an embodied thing in the world. One problem here is that AI is incapable of physical embodiment. I mean, imagine you tried to ‘physically embody’ your favourite AI model, by getting a little robot to carry your laptop around. How would that help? The functionality of AI is neither constrained by, nor tied to, your laptop! As an abstract thing that doesn’t persist across time, AI has no spatio-temporal existence. Moreover, even if you could somehow ‘embody’ an AI model in something physical, the model wouldn’t be aware of being embodied. This puts AI at a big disadvantage when approaching normative matters around interactions between living things, which is the heart of moral philosophy. For instance, part of why I know I shouldn't intentionally and unnecessarily cause another person pain is because I feel pain myself. But it’s not just pain that AI has no awareness of: it’s anything physical; it’s anything, at all.

A simulation?

I’ll finish by briefly posing the idea that AI’s lack of these four qualities — particularity, subjectivity, the capacity to reason, and physicality — means that when AI is ‘doing philosophy’, it’s really only simulating doing philosophy. I touched on this idea above, when considering whether humans could do philosophy if we had no free will. An analogous argument can be made about games. That is, I believe that when AI plays a game it’s not really playing a game: it’s just simulating doing so. This is because AI can’t agree to play the game, choose not to cheat, derive objective achievement from winning, and so on. And I think those kinds of things are necessary to playing games, as opposed to merely moving pieces around boards, or kicking balls around pitches.

I do think there’s a sense in which this simulation idea also applies to AI doing philosophy, particularly if my argument about the value of subjectivity carries across to all kinds of philosophical activity, including writing those descriptive essays. Sadly, it would also apply to us, if we had no free will. That is, I think my ‘but we’d still be aware’ response does hold weight in relation to some free-will constraints. But if it wouldn’t work for playing games, then I fear it also wouldn’t work for doing philosophy — as opposed to, say, 'being exposed' to philosophy. Sure, we’d still be at an advantage over AI, since AI’s lack of phenomenological experience would mean, again, that it wouldn’t be aware of its exposure to philosophy. But the advantage we held wouldn’t be an advantage at doing philosophy.

None of this is to deny the likelihood that AI will soon begin to offer convincing new answers to some of the hardest philosophical problems. It does, however, underscore the idea that being good at doing philosophy will be relatively valuable in the Age of AI’s labour market — as one of the core intellectual pursuits that cannot be entirely outsourced to AI. This is in part because, unlike with most other academic disciplines, the job of the philosopher is not simply to uncover the right answers. That is, in scientific disciplines, it can be enough to have landed on a solution that works. This approach can lead to bad unintended consequences. Nonetheless, knowing the reasons behind a correct answer isn’t crucial to those kinds of project: knowing them simply holds extra instrumental value. Whereas, knowing the reasons for the sake of knowing the reasons takes us into philosophical territory. This is something we cannot outsource to AI, even though its efficient methods mean that it will reach some truths faster than us. Jumping to the end means missing out on the reasons, however, and even if AI offers you ‘its reasons’ along the way, you still have to be convinced by those reasons. And becoming convinced by any reasons involves you — you, yourself — doing philosophy!

This personal element makes doing philosophy like writing poetry. In the same way that it means something different if someone you care about writes a poem for you, than if they get AI to write you a poem, we humans are specifically interested in what other humans think and conclude about the truths of the world. Again, it's not that AI won’t give us valuable outputs: I still want to receive the AI poem! But think about the difference between a beautiful sunset and a beautiful painting of the sunset. You don’t have to believe that the painting is more beautiful than the sunset to have a special interest in the painting, as a human creation. Similarly, if a dog accidentally ‘paints’ a beautiful sunset, by knocking over some paint cans next to a piece of paper, then that’s different again.

We hold a special interest in beautiful, and otherwise valuable, things that have been created by other humans. This is because those things represent human achievement. But it's also because it means something different, and more, to be delighted or moved by a person, than by an animal or a machine — particularly if that person has intended to delight or move you. Sure, you can be delighted or moved by a machine, but that's a thinner experience, not least for the lack of intention. Now, philosophy can also delight and move, but most of its value is in insight. Demand will persist for philosophy written by humans, therefore — demand from human readers, and demand to feed AI systems to satisfy human readers — because philosophy involves searching out truths related to what it's like to be a person in the world. Human philosophers know what that's like. Whereas, AI doesn’t even know what it’s like to be AI.

Nonetheless, I’m very aware that it was those ‘prompt theory’ videos that prompted me to write this piece. And also that it may have been your interactions with AI that prompted you to read it, and — if my first argument holds — to develop stronger objections to what I’ve argued. To that end, if it turns out that my views about consciousness are incorrect, then I hope someone will persuade me over to the correct side, whether it’s you or AI. We’re living in the Age of Philosophy: it’s a great time to be a philosopher! It’s funny, really, that it took a brainless, mindless, non-entity to bring us here.

.png)

![Push is Faster [using std:cpp 2025] [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)