Adafruit, a New York City-based online retailer that sells a variety of electronic components and tools, received its first significant bill under the new U.S. tariff regime on 29 April 2025.

The damage? US $36,000.

Escalating tariffs made that bill several times larger than those Adafruit had previously paid. “If it weren’t for the 125 percent, plus 25 percent, plus 20 percent tariffs,” the fee may have been around $5,000 to $6,000, explains Adafruit founder and engineer Limor Fried. She said the shipment was valued between $70,000 and $80,000, and that some items in the shipment faced tariffs as high as 175 percent.

While the Trump administration has already changed its tariff policy several times in recent weeks, this new expense isn’t a one-off. Barring a complete reorientation of U.S. tariff policy, this is the new reality for companies importing electronic components to the United States.

The tariff situation is challenging for many companies that build or sell electronics, but it poses specific challenges for the maker community and companies like Adafruit, which sells some components designed in-house. Companies specializing in components, single-board computers, and modular or repairable electronics often source from dozens or hundreds of suppliers outside the United States, which makes them sensitive to tariffs. And the nuances of U.S. tariff policy can lead to unintuitive downsides.

Tariff Bills Arrive as Confusion Reigns

Adafruit is one of many companies that have felt the impact.

Wyze, a Seattle-based company that sells smart home electronics like security cameras and locks, announced on social media that a recent shipment valued at $167,000 was hit with a tariff bill of $255,000. YouTuber and electronics blogger GlytchTech went viral after posting a $2885.29 tariff bill on equipment that shipped from China before 2 April, when President Trump officially announced the administration’s “reciprocal” tariffs. And Allen Walton, owner of surveillance electronics company SpyGuy, told Wired he “doesn’t know if he should replenish his stock.”

On 12 May 2025, the Trump administration announced a temporary tariff deal that reels tariffs back 115 percent from prior levels, which reportedly nets out to a tariff of 30 percent on goods from China. But the deal offered cold comfort to Adafruit and other companies that have already paid steep tariffs. “Just because it changed today, I can’t get back what we were charged,” says Adafruit’s Fried. This adds an element of risk, as tariffs may change after a shipment has left its country of origin. What matters is the rate when shipments arrive.

That being said, Fried also noted a gap between the announcement of trade deals and their implementation. Though the White House currently leads U.S. tariff policy, it’s up to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection to handle the specifics of how changes apply to thousands of product categories. The frequent swings in policy have led to the agency playing catch-up. As a result, it’s often unclear what the tariff will be until the bill arrives.

“A statement on the news doesn’t mean anything until customs actually formulates how each tariff code is charged,” Fried notes.

A Game of “Musical Factories”

The Trump administration’s tariff regime has the stated goal of rebuilding U.S. domestic manufacturing. Whether that will happen is unclear, however. The complex dynamics of supply chains and international tariffs means the winners and losers aren’t what you’d expect.

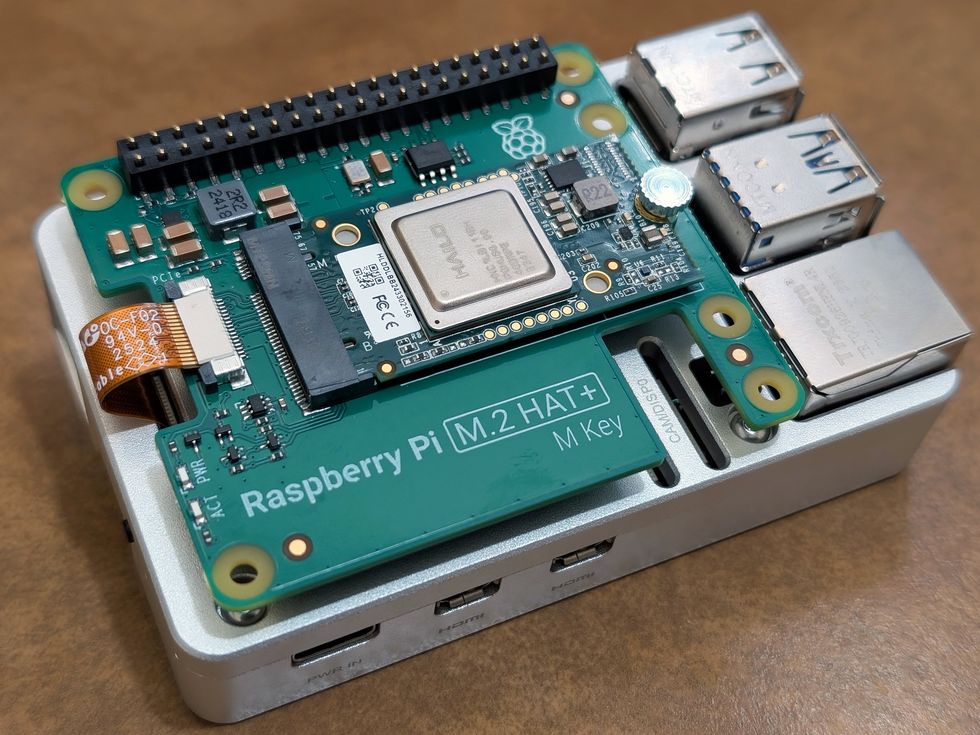

Raspberry Pi, a U.K.-based maker of single-board computers used by companies to make everything from digital billboards to handheld game consoles, manufactures its computers in the United Kingdom. While manufacturing costs are often a bit higher in the U.K. than in China, this strategy is now tariff-efficient, as the company faces lower tariff rates than many of its competitors.

“We are lucky that the majority of our product is in the 10 percent tariff world, which is kind of the best place that you can be,” says Eben Upton, Raspberry Pi’s founder.

Upton suggests that for some manufacturers, it might become more cost-effective to use Raspberry Pi components manufactured in the U.K. and then complete assembly in the U.S., rather than assembling products in China. “You could imagine a future in which we sell less in China, and more in the U.S., and systems integration moves,” he says.

California-based modular laptop manufacturer Framework, meanwhile, builds its laptops in Taiwan. “There’s currently no tariff impact, because there’s a pause on those tariffs for electronics [such as laptops] specifically,” says CEO and founder Nirav Patel. However, the company does face tariffs on some components that are sourced in China, such as power adapters.

Patel compared the state of manufacturing to musical chairs. In this game of “musical factories,” electronics companies may shift production out of China to other non-U.S. countries, such as Vietnam, India, Taiwan, and Malaysia. But Framework has little say in where component manufacturing ends up and may not be able to absorb price increases caused by changes in its supply change.

“We typically don’t have the volume to drive major manufacturers to set up new infrastructure,” Patel said. “We’re operating downstream of decisions that our suppliers are making on their own.”

In some cases, this could force companies to delay products in the United States, or lead to price increases that see U.S. customers paying more than those overseas. That was temporarily true for Framework, which paused U.S. pre-orders for the Framework Laptop 12 in early April. Pre-orders were only made available in the United States after temporary exemptions on specific electronics, such as laptops, were announced.

Learning Electrical Engineering Could Get Pricey

So, why doesn’t Framework just build in the United States? Patel says it again comes down to oddities in tariff policy.

As mentioned, laptops from Taiwan are currently exempt from tariffs. “The components that go into products, for the most part, are not exempt,” says Patel. “So, for companies that do want to set up manufacturing in the U.S., the barriers in many cases are higher than doing that assembly outside the U.S.”

This also affects retailers that sell components to students, hobbyists, and engineers.

Nearly all the products sold by Adafruit, for example, are not assembled electronics but instead the parts used to make them, such as sensors and capacitors. Most of these components don’t qualify for current tariff exemptions on finished products. And in some categories—including power supplies, connectors, and LCD displays—few if any components are wholly manufactured in the United States.

Fried thinks a general increase in pricing for electronic components is likely, and that some prospective engineers will find themselves priced out of the equipment and components they need.

“It would be a shame if the tools and equipment needed to learn how to do electronics, engineering, and robotics tripled in price,” says Fried. “If that price is no longer going to be $25 per student, and now it’s $75 per student, maybe some students won’t be able to afford it. But we’ll do the best we can.”

.png)