In late August it was announced that the Arts and Humanities Division at the University of Chicago would be pausing graduate student admissions for all departments (excepting philosophy and musicology, which had recently undergone their own separate admissions freezes) for the current academic year. This accompanied a series of reports of additional restructuring proposals and cost-cutting measures—including potentially scaling back UChicago’s famed language programs—to address the university’s “historic funding pressures.”

On the editors’ Slack, we tried to process this news. Many of us had been educated at UChicago, and almost all of us consider it a bastion of humanistic learning—a kind of “Benedict Option” for people who love books—at a time when so many universities seem to be abandoning their responsibility to provide a truly “higher” education. Even though it was part of a steady drumbeat of bad news for American universities, the pause at UChicago therefore struck us with particular force, causing us to reflect back on our own experiences in graduate school, both at UChicago and elsewhere. Was it ever possible to lead the life of the mind in graduate school? Is it now? And amid political attacks and the dimming job prospects for humanities PhDs, what are the best arguments for why universities ought to continue to support graduate programs in the humanities?

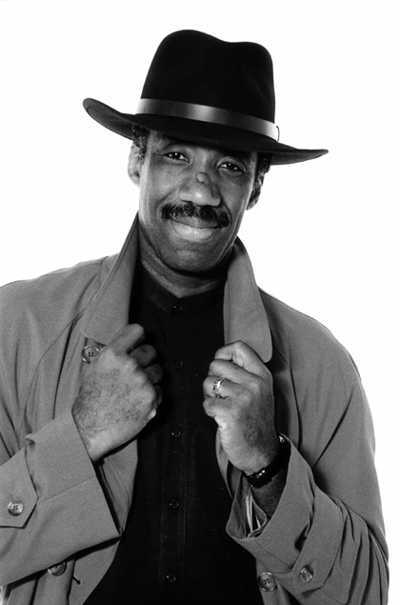

Those conversations inspired the series of dialogues we’ll be posting here in the next couple of weeks, beginning with this exchange between Point editors Becca Rothfeld and Ben Jeffery. Becca is the nonfiction book critic for the Washington Post and a Harvard philosophy Ph.D. student on “indefinite hiatus,” and Ben is a graduate of the Committee on Social Thought, who is now a Harper-Schmidt Fellow and Collegiate Assistant Professor in the Humanities at University of Chicago.

Ben Jeffery: One of the things I started thinking about in the wake of the admission freezes at UChicago is how the state of graduate education today compares to my own experience in a Ph.D. program. (I started in 2012, back in what was outwardly a more stable period.) Having spoken to a number of current graduate students, my impression is that there’s a lot of understandable shock and discouragement about the interruption, and a lot of lingering uncertainty as well—sure, if it is just a one-year pause then maybe there isn’t so much to be worried about. But is it? I think it’s telling that there doesn’t seem to be much instinctive confidence in the idea that this is only a temporary reset, rather than the herald of something worse to come. But I also think that in the circumstances it behooves us to reflect on the “normal” that it’s a departure from. Just how well was it working? Obviously, this is a question that goes far beyond UChicago.

So on that topic, let me start with an idea that seems pretty uncontroversial: humanities research as it’s been practiced, especially over the last two decades, produces a tremendous amount of waste. You could put this either in terms of the number of people coming out of graduate programs who are notionally qualified for jobs that they’re never going to get (a trend that’s been going strong for at least fifteen years, if anything getting worse) or more broadly—and perhaps more importantly, in a way—in terms of the sheer weight of books, articles, arguments and professors the system generates that have almost nothing memorable to say, and that hardly anyone could be expected to care about in good conscience. As I said, neither of these things is new. In fact, both of them have been almost quasi-permanent features of the background ever since I started in graduate education. But I think perhaps what’s new about the current moment is that it’s suggesting something about how structurally fragile and unhealthy that whole situation was. For a long time, I think my impression was that although the excesses of the system were unfortunate in some ways—as well as being fairly brutal in human terms—it was mainly a problem for individuals rather than the system itself. You could certainly do your best to adapt and survive and produce something worthwhile, but whether you succeeded or failed, the industry was still going to roll along more or less as it had before. Some people would get jobs. The programs at good universities would still fill themselves. The losers would have to figure out whatever they could.

That perspective seems slightly naïve to me now. On the one hand, I suppose it’s possible to make an argument that, despite appearances, it’s actually a mark of health in a humanities ecosystem that there can be room for a lot of activity that doesn’t seem to matter very much—because it’s like a sort of compost production?—and perhaps on those grounds we should regret whatever constrictions or collapses in graduate education might be coming down the pike. But for one, I don’t know if that perspective is true. More to the point, if the prevailing way that a training system operates basically has the effect of inculcating an underlying feeling of being useless or unwanted in the bulk of people who go through it, it seems to me that it then shouldn’t be a surprise if that eventually starts to eat into the institutional foundations, because of course it’s going to make the whole thing seem less like a way of life that’s worth being loyal to.

So perhaps my question here is about what a more confident or healthy world of graduate education would look like, if there can be such a thing, and whether thinking in those terms offers any help for trying to see our way past the latest evolution of the crisis. Somewhat connected to this, another impression I’ve had is that, especially over the last decade or so, the dominant way that people within the academic and para-academic systems have tried to defend themselves against feelings of superfluity and meaninglessness has been to valorize the idea of “the public,” and to think in terms of a gap between the academic world and public life that they wanted their work to be able to somehow bridge. The spread of little magazines is one expression of this, but so is the growth of public-facing academic books, and the kind of fusion of academic work and political activism that we’re all so dismayingly familiar with. I wonder if in some ways we’re now at the far end of that period—where the guiding problem isn’t going to be connecting with the public so much as finding ways to re-establish the boundaries between the academic world and its exterior. It turns out we might miss the ivory towers once they’re gone.

Becca Rothfeld: Forgive me, Father, for I do not want to have doubts about the academic humanities on the eve of their decimation—but I’m not sure that I will miss the ivory towers when they’re gone, or at least, what I will miss about them strikes me as incidental to their self-conception and their stated aims. I will miss the role they played, often despite themselves, and I will miss the people who populated them, often ambivalently and always in abominable working conditions. And it goes without saying that if the humanities ever ceased to exist, I would not merely “miss them”; I would cease to have a reason for living. But I’m not sure that the humanities could ever vanish—we need them too much, and we perpetuate them too helplessly, just by dint of being the kind of creatures we are—and I’m even less sure that the academy in its present incarnation provides the best forum for their continuation. That isn’t to say that I wouldn’t go to the barricades to protect the ivory tower, now that the philistines are at the gate. Rest assured: I plan to. But I’d rather go to the barricades for something I could stand behind with less trepidation.

What did I love about the university during my decade inside it? I loved the ideal, rarely realized, of an intellectual community—a group of people committed to thinking together rather than competing against one another for a vanishingly small spate of jobs. And I loved the promise, equally notional, that there might be a retreat from worldly preoccupations, a place reserved for thinking, just for the sheer delight of it. Above all, I loved the kind of people the university attracted (and often ended by demoralizing, if not completely destroying): people eager to pore over The World as Will and Representation line by line for over a year, people for whom the life of the mind is a necessity and, more importantly, a joy. And if I didn’t exactly love that academic humanities departments are pretty much the only durable and entrenched institutions in the anglophone world dedicated to the study and preservation of the arts, I knew that it was true. And if I downright hated that so many of us were consigned to conditions of poverty and precarity, I had no choice but to pretend our plight was justified by the project we were jointly committed to maintaining. But was it?

You’re catching me at a moment of acute skepticism. I’ve just returned from teaching at the Matthew Strother Center, a place that’s hard for me to describe in less than half a million words. In brief: five students of all ages and all professions come to a farm in the Catskills, where they stay for a week for free, without their phones or computers. They don’t know in advance what book the faculty will assign them, but they show up anyway. During the day, they work on the farm and attend a three-hour seminar. At night, they participate in “salons”: during our session, we staged a performance of Plato’s Symposium and sang an arrangement that one of the students, a retired choral director and organist in his late sixties, prepared for us. We were not expected to produce anything. The goal was the hardest and best thing in the world: to read a book together and try to understand it.

That book was The Gay Science—which is in large part about the shortcomings of the modern university. Nietzsche describes its resident specialists as “grown into their nook, crumpled beyond recognition, unfree, deprived of their balance, emaciated and angular all over except for one place where they are downright rotund.” I think I know what he means. I’ve taught Nietzsche in the university, and I’ve taught him on a farm in the Catskills, and there is no comparison.

So where does this leave me, a conflicted defender of the university, an academic exile by choice? We need humanistic institutions. The humanities are not the kind of thing we can—or would want to—do alone. But must we content ourselves with the humanistic institutions we have? Yet it isn’t obvious that the model of the Center could ever be scaled up to accommodate a whole nation, and it certainly is obvious that any broadscale change in humanistic education is a lamentably long way off. For now, for better or for worse (and I’m often convinced it’s very much for worse), the university is the best we have. I love it; I hate it; I resent that I need it. I wouldn’t miss it if it vanished—but of course, I also would.

Ben Jeffery: I do think that practically speaking it’s a matter of working with the university that we have rather than hoping for a wholesale reincarnation. But I agree with you about how vital the affective component is to thinking about the challenge. Personally, I loved graduate school—part of that was probably because I was in a lovably weird and serious Ph.D. program, and another part of it was almost certainly because graduate school consisted of a whole series of things I would have done even if I’d been left on my own. But it was also for all the reasons you’ve just articulated, however fitfully realized in practice—the sense of being amplified by the company of other people who wanted to think carefully; the feeling of collaborative otherworldliness; the sheer energy that you can pick up on by being around genuinely brilliant people. On the latter score in particular, top-end American universities still strike me as being pretty special places: you really do meet an unusual concentration of extraordinary individuals, and it has a catalytic effect (to me, in any case) that you mostly can’t replicate just from books or discussion groups. So there’s a sort of vertical thrill to it as well as a horizontal one.

At the same time, everything you’ve said about the institutionalized demoralization is also so obviously true. It feels like a force of nature sometimes rather than the effect of man-made structures. At the risk of repeating myself, it might be that the greatest perversity of the current system is that it takes an activity that has so many obviously happy and enriching emotions inherent to it and then forces the young people who are most drawn to that activity to filter everything through feelings of anxiety, disposability and anonymity. I suppose it’s true that to some extent that’s just to describe late-capitalist working conditions in general—but still, if it’s true anywhere that we can change what we’re doing by changing how we imagine it, surely it’s true in the world of the humanities. Aside from the question of what a better sort of “productivity” might look like in such a world (and I have mixed thoughts about that), is it really not possible to imagine an approach to graduate education that would be qualitatively more effective at instilling a sense of collective purpose in its members, and thus helping people to feel like what they’re doing matters? And when I say “collective purpose” obviously I have something connected to the value of the humanities themselves in mind, rather than any narrowly political targets. Call me a sap, but I’d like an institutional humanities that was better at taking care of its kids, so to speak. It’s a question of material support, but not just that.

The last thing I’ll say for the moment: I’m curious about what you think of the university at the graduate level as a place for intensifying and/or giving deeper shape to the sort of joy that attracts people to the humanities in the first place. Their role as emotional incubators, I guess. What are the good parts about how it works now, and what are the better possibilities? At the moment, what I suspect happens to a lot of people is that they succumb to a certain kind of ego rigidity that gets installed in the course of internalizing the various professional norms that are meant to (maybe, hopefully) one day land them a job. And this has the side effect of draining much of the vitality and creativity out of the enterprise, too. But I also don’t think that it is or has to be the whole story. (Albeit another thing Nietzsche said was that scholars are incapable of giving birth, so maybe in some deeper sense it is the real story.) Anyway, to speak again from my own experience, there are all sorts of ways in which my own ability to take pleasure from thought was developed and changed, and not just given space, by the infrastructure and discipline of the university, and especially the intellectual standards it introduced me to. That seems like a type of nurturing authority that’s worth defending.

Becca Rothfeld: I agree that universities are the only institutions entrenched and widespread enough to provide a humanistic education at scale, at least for the foreseeable future. But even the continued existence of universities in anything close to their present form is far from a given. Before Trump took a wrecking ball to higher education, reforming the academic humanities was a distant possibility, one that few if any of their foremost practitioners seemed to take seriously. Now, what some might call “the vibe” is very different. The humanities simply will not survive if they do not change dramatically. Reimagining them is not just a live possibility but our only hope.

The fact is, they have long been sick. Even before the recent upheavals in higher education, both at the University of Chicago and elsewhere, they were plagued by dwindling enrollments and vicious insularity. Much of the problem was material. Students forced to weather a brutal job market chose to major in more practical fields; academic humanists, desperate to win back some of their bygone cachet, took to imitating the tone and stylistic tics of scientists. However much I sympathize with the architects of this shift, it has been a losing strategy—both because it made the humanities singularly unappealing to most of the people who might otherwise have pursued them and because it warped them beyond recognition.

You ask which parts of the current model are worth keeping and which ought to be jettisoned. This is the question, given that the humanities have to change in one way or another, and I don’t have a satisfying or complete answer, much less one I could articulate in close to a thousand words. My strongest conviction is that extra-academic institutions like the Strother Center can help provide one. Maybe these projects can never grow large and powerful enough to facilitate the bulk of humanistic education in America—though maybe they can, and so many of them have sprung up in recent years that I’m almost optimistic—but they can certainly provide models for the more sclerotic institutions that are slower to change and experiment. What can they teach us?

One thing that ought to change—perhaps the primary thing—is the expectation of constant output. Another thing that ought to change is the fetishization of jargon. But as you note, something that’s both good and unbearable about the university in its current state is its commitment to rigor and expertise. A text isn’t a free-for-all; even if there are no definitive right answers about its interpretation, there are certainly any number of wrong ones, and years of study of an author and her tradition prepare us to identify them.

Yet the way rigor and expertise are often understood in the academy leaves much to be desired. I would be hard-pressed to explain in so few words—and this is already too long!—what distinguishes the distortive kind of expertise that Nietzsche railed against from what I regard as a fruitful kind. Perhaps the briefest way I can put it is that it’s good to know what you’re talking about, but the humanities are not like the sciences, and “knowing what you’re talking about” sometimes requires taking a lengthy detour. If the ultimate topic of any line of humanistic inquiry is what it’s like to be a person, then no artifact is irrelevant. Reading, say, Swann’s Way alongside The Tale of Genji can illuminate the theme of jealousy. And because humanistic artifacts occur within traditions, which are messy and capacious, reading only a single author and the secondary literature about her—or reading only work from a given period—is a liability. It prevents a humanist from understanding the context of the work at issue.

This claim brings me back at long last to one of the questions we started with: whether pivoting toward the “public” can save or at least reinvigorate the humanities. I’m biased—I’m a public humanist, after all—but I believe it can, precisely because I believe there need be no dichotomy between expertise and public interest. Expertise of the sort I have tried to paint as unnecessary, off-putting, and even, per Nietzsche, deforming—pseudoscientific expertise, cooked up as a way of artificially investing the humanities with the gravitas the sciences now command—may be incompatible with public intellectualism, since it helps itself to technical language, wades into arcane discussions and almost prides itself on its ugly aridity and incomprehensibility. But expertise of the sort I am commending is just a matter of learning more about something of obvious interest to everyone. Some people have additional time and inclination to learn more about things of obvious interest to everyone. But if something is not of obvious interest to every human being, it can be of no interest at all. A good guiding principle for the humanities moving forward, perhaps, is this: if there is no way to explain to a curious and thoughtful civilian—my private word for nonacademics—why this question is relevant to her life, then perhaps it isn’t relevant, period.

And if people have become incapable of mustering interest in gloriously useless subjects, like Sumerian grammar or the logic of conditional statements? What then? Well, then we need to create a different kind of person. And how could we hope to accomplish such a task without enlisting the public, which after all consists of the very people we need to convert?

Stay tuned for a follow-up to this dialogue, in which other editors on staff will reflect on and respond to the points Becca and Ben have raised.

Lisa Ruddick on the “malaise without a name” that afflicts English grad students.

Joseph M. Keegin’s “Commit Lit.”

Nikhil Krishnan on Bernard Williams’s model of a life in philosophy.

Andrew Kay’s twin journeys on the academic job market and the dating market.

Helena de Bres’s online series on academic philosophy and the meaning of life.

.png)