It worked so well. When we tested in central Oslo, walking to the office and home. Parking in the street. The occasional taxi ride home. Even suburban customers who drove back and forth when they went out. Our geolocation engine was spot on, turning home alarms on and off exactly when they were supposed to, without any human input at all.

Then we got user feedback from a customer. The alarm always triggered when he opened the door.

What was happening?

Turned out, he lived right next to an 80 km/h speed limit road. He covered the geofences in seconds, then parked right outside his door. An edge case for sure, but just the first of many we would experience and solve. Combined, that edge was pretty wide.

The middle 75% of any product can be solved from your desk. The really delightful products thrive at the edges, where the unexpected happens and most competitors give up.

Four kinds of edges

The technical edge is especially prevalent when bits meet atoms. You test on a brand new iPhone Pro. They carry a tired Android, and their kid set the clock to dodge screen time limits. The login code arrives and “expires” on the spot. Hotel WiFi shows your screen but blocks the request. The app spins forever and looks broken.

“Oh, sweet child”, is what goes through my head when someone announces a feature built on geolocation. You’d think GPS was pretty reliable, but suddenly a phone will report its location 200km away for a minute, then jump right back. Superman problem, we called it.

The middle case runs on reliable connectivity and modern hardware. The edge case runs on whatever your customer actually has in their pocket, in whatever environment they actually inhabit.

The workflow edge isn’t about technology at all. It’s about the gap between what happens inside your company and what the customer sees on their screen.

The Norwegian Mail will occasionally reroute your mail before it leaves the sorting station if they realise the package is too big to fit in a mailbox. Operationally, this is smart. They’re saving time and ensuring successful delivery. In theory, it’s also great customer service.

Except they use the same messages as when the mailman actually tries to deliver and fails. So you get two messages at 7AM, making it look like they couldn’t be bothered and just pretended to deliver it.

The internal workflow is optimised. The external message is broken.

The psychological edge is harder to spot. For most families, kids’ smart watches are an extra little piece of mind, but never really top of mind. They check it occasionally, appreciate knowing their child got to school safely. They are nice to have.

For others, those with anxious kids for instance, it is a lifeline. When your product fails to deliver the necessary confirmations, you break the deal you implicitly made with your users, and anxious kids don’t trust easily.

The feature that 80% of users interact with weekly becomes essential for 1% of users who depend on it daily. When it breaks for that 1%, the emotional cost is so much higher than the technical severity suggests.

You can’t identify these edges through usage analytics alone. Two users with identical behavioural patterns might have completely different emotional responses in your product’s reliability.

The cultural edge surfaces when you enter new markets. It can be as simple as an intense focus on energy efficiency (turning off lights when leaving the room or obsessing over the thermostat), or more complicated, like the fact that phone numbers aren’t synonymous with a single person in some countries.

Building from Northern Europe gives you a pretty standardised setup. People have the same phones, newer models. Better computers. Same references. Same buildings. Scandinavians want it warm, costs be damned. Other Europeans will take the cold to reduce the bill. What feels like a universal product decision in Oslo becomes a cultural mismatch in Milan.

The further away you go, the more it differs. You assume one phone number equals one identity. You design energy controls around “set it and forget it.” You build sharing patterns around nuclear families. Then you ship to a market where none of those assumptions hold, and your product feels fundamentally misaligned with how people actually live.

How to find them

Here’s the challenge: you can’t imagine the problem, so you won’t spot it during user conversations. Traditional user research asks people to describe their needs and frustrations, but edge cases hide in combinations of circumstances that neither you nor your users think to articulate.

Three things help.

First, focus on where your product might break during actual use, not where it works in testing. Look for combinations of constraints. Speed and proximity. Trust and failure. Identity and sharing. Performance and diversity.

Map your product’s critical moments. The places where atoms meet bits. Where internal state meets external messaging. Where user emotion peaks. An authentication flow on flaky connectivity. A notification that implies human action when it’s automated. A feature that some users depend on for emotional safety while others browse casually.

Don’t try to imagine every possible edge case. Instead, identify the dimensions where edges are likeliest to appear, then instrument those areas to catch them in the wild.

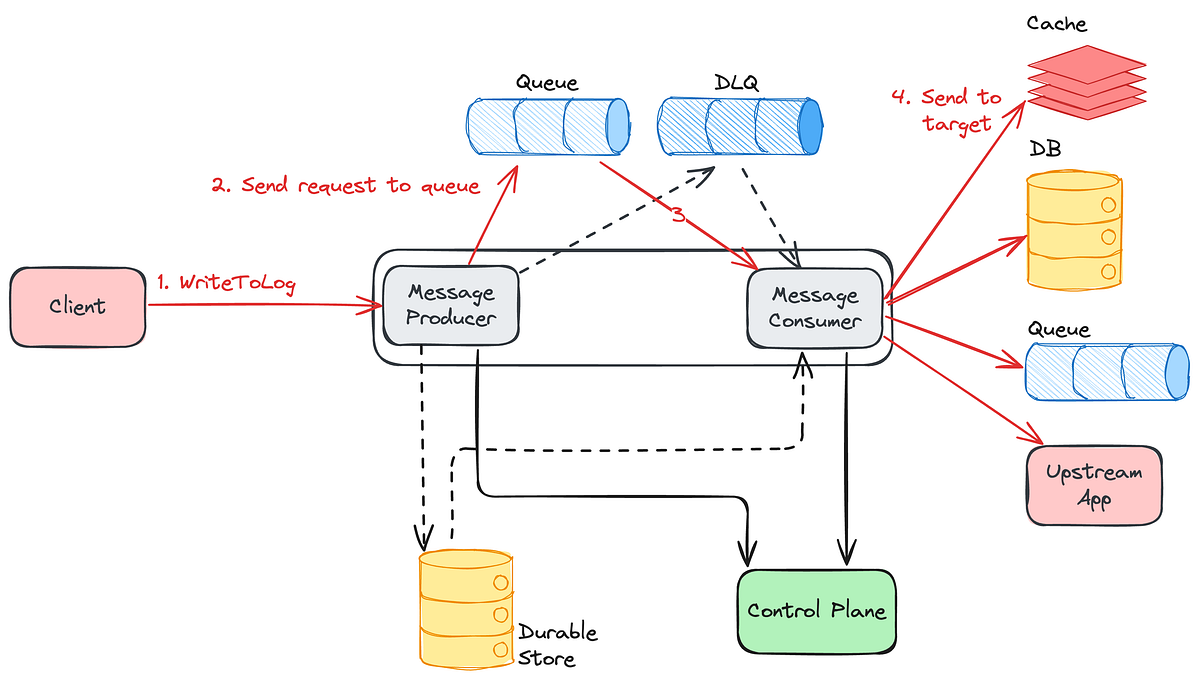

Second, make sure your logs are detailed, but product manager friendly. Raw technical logs tell you what happened. Product‑friendly logs tell you why it might have happened, who it affected, and what they were trying to accomplish.

Your customer support tool is your greatest ally here. Every confused email, every frustrated chat message, every support ticket that takes three rounds to resolve contains a signal about an edge you haven’t handled.

Look for similar patterns. The “unique situation” that three different customers describe in three different ways is probably the same unhandled edge.

Third, track not just the what went wrong, but the context around it. Device type, network conditions, time since last successful action, user group markers. You’re building a map of where your product breaks and for whom, so you can predict the next edge before a customer hits it.

What to do about them

When you find an edge, handle it. Even if you’re only doing it for “one person.”

That one person represents an entire group you haven’t discovered yet.

The edge is always wider than it looks from the first report.

Here’s how to handle it: Acknowledge the issue in your product (ideally before the user notices). Explain what happened in language that matches the user’s mental model, not your technical architecture. Fix it in a way that accounts for the entire group, not just the individual instance.

This is where edges become differentiation. Your competitor says “works for most users” and moves on. You care enough to say “we found this edge and handled it”, earning loyalty from a group that thought they were invisible.

The eval approach

AI products make this even more critical. When your output is stochastic, edges aren’t exceptions. They’re inevitable. The same model that nails the answer one time will confidently deliver something completely wrong the next, with no obvious pattern to predict when.

The eval approach that AI teams have adopted is just systematic edge case testing. Build a library of failure modes. Keep expanding coverage as you discover new ways things break. It’s like unit tests, but for things that shouldn’t be possible to get wrong yet somehow are.

The principle works for any product. Treat every edge case as a test case. Build your library of situations needing special handling. Keep expanding as customers show you combinations you didn’t anticipate.

Where it leads

The middle 75% keeps you in the game, but the edges win loyalty.

When you handle someone’s “unique situation” that nobody else bothered with, you don’t just solve a problem. You show that you see them, that your product was built with actual human diversity in mind, not just the idealized middle case that exists in your test environment.

It should feel like this: a customer hits an edge, expects it to break like it does everywhere else, and discovers you already thought of it. They tell their peers. They become your evangelists. Not because your core features are better, but because you cared about the edge where they actually live.

.png)