By Allison K Williams

“Shitty first drafts,” says Anne Lamott, “are how writers end up with good second drafts and terrific third drafts.”

Alexandra O’Connell calls it the Ugly Duckling Draft. Austin Kleon, The Down Draft (just get it down). In Seven Drafts, I call it The Vomit Draft, but also quote Jenny Elder Moke, “y’all quit calling your first drafts garbage. What you’ve got there is a Grocery Draft. Put everything you bought on the counter and figure out what’s for dinner.”

My own writing process doesn’t involve an entire shitty first draft, because I don’t write to the end before I go back and fix. Each day I work on a novel, I start by revising what I wrote the day before, cleaning up that scene and feeling the rhythm for the next one. At the end of a writing session, I leave rough notes for the next scene—scraps of dialogue, action details, character development that must happen.

Yesterday’s writing is the springboard to a better draft. When I sit down to those notes and fragments, Yesterday-Me has left a glorious gift for Today-Me: the gift of knowing where to start. Like that Dutch thing where they abandon their children in the woods in the middle of the night to make them find their way home (not kidding!), but with a compass.

Pick a direction and go.

So what happens if you ask someone else to build the springboard? To hand you that compass?

I was AI-curious, we might say. I’m attending a webinar next week with Jane Friedman about ethically and usefully using AI—highly recommended if you’re also AI-curious—and I’d heard good things about using AI for marketing copy. I have a professional subscription to Claude, which comes with some privacy protections.

With AI, context matters. I wanted to create some video ads for the Ultimate Revision Weekend, a virtual intensive I’m leading this weekend. I suck at video. So I asked,

Look at this website and suggest some Instagram Reels to advertise, including visuals and advice on shooting

Oh boy did Claude deliver. Scripts, shot lists, suggestions for subtitles and images and music. I still had to stage them and shoot them, but the plan got me (and my video guy) started.

What if the machine could do more? Could it write a blog?

I fed Claude links to three previous blogs I’d written about finding comp titles for querying:

Please look at these blog posts, and write an 850-950 word blog post in the same voice, for an audience of writers, about finding the comparative or competitive titles to their own book. They need this information to write query letters and also to understand the market. The author of the blog is an expert publishing consultant who has helped authors become bestsellers. She is funny and direct. The blog post should contain immediately actionable information.

And Claude came back with a draft. A little smarmy, a little salesy, a little cheesy—but a springboard into revision.

And I revised a lot.

Claude’s first paragraph:

If I had a dollar for every time an author hyperventilated in my Zoom chat about comp titles, I’d be typing this from my private island instead of my living room with the cat trying to sit on my keyboard. Let’s be real: finding those magical “comparative titles” for your query letter feels like trying to locate your soul mate by speed-dating in the dark while wearing noise-canceling headphones.

What I revised to:

I hear two common ways authors think about comps, and they’re both wrong. Comp titles—short for “competitive” or “comparable”—are the books you name in your query or proposal to show that readers are eager for books like yours. They’re a shorthand way to discuss your book’s themes, subject matter, cultural relevance, or the way readers will feel when they experience your story. Finding the right comps means reading, doing market research, and understanding why people (including yourself!) buy books. Unfortunately, the process can be tricky and tedious when you first start looking, and two common feelings come up.

I didn’t use much of Claude’s actual text. In the rest of the blog, I changed the main metaphor from “being a detective” to “being in high school and trying to find your crowd.” I replaced smarminess with my own humor. But the suggested headings guided me through what information to provide, in what order.

I double-checked Claude’s suggested titles (sometimes AI just makes shit up) and told it, “Include only books published 2022-now.” Some examples contradicted my own advice (“don’t pick runaway bestsellers”) and I did the same research I recommend to authors: let Amazon’s algorithm show me similar titles.

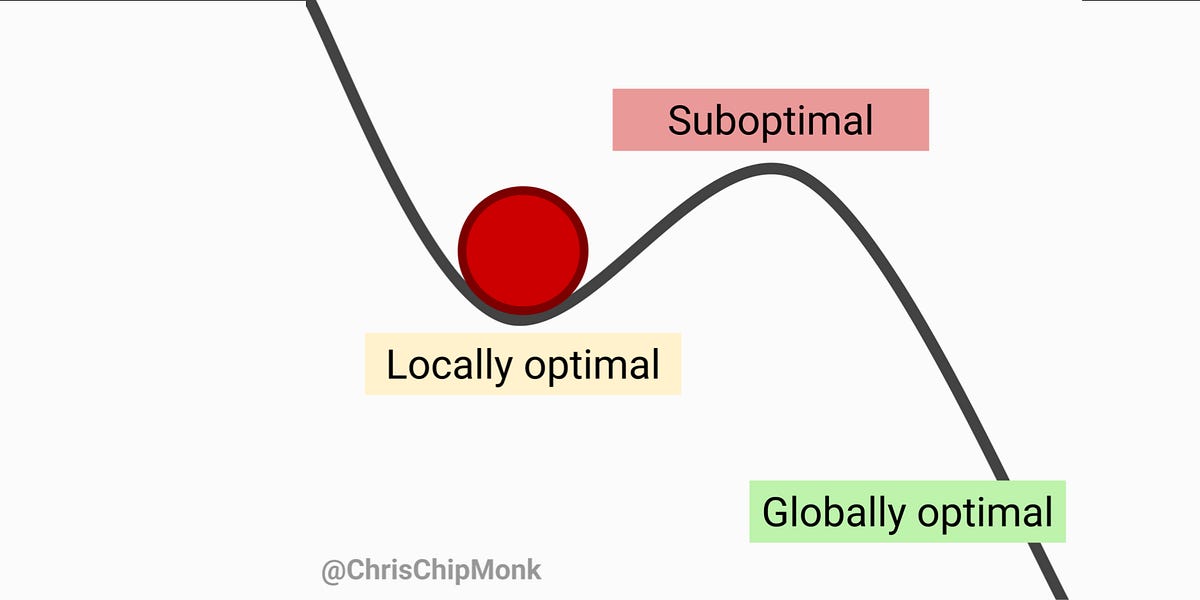

Timing my work, I spent about 45 minutes revising the rough draft. Normally, I’d write a Brevity Blog essay in 60-75 minutes, so it saved me 25%-40%. I didn’t save much time, but I did put my ass in the chair and get it done. The tool of AI gave me an outline to work with and something fun to try. The compass pointed towards my writing home—then I walked there myself.

I wouldn’t advise AI for a book, I start to say. This was just something simple. But then I remember I brainstormed about a tricky scene—a heist—with ChatGPT. Unfortunately, ChatGPT wouldn’t tell me how to sneak a body out of a party, because it’s not supposed to help criminals. It took a lovely conversation about roofies with a British pubkeeper to work that one out, but it was my frustration with AI’s refusal that made me seek a human source.

AI is a tool. And just as a hammer can build Habitat for Humanity or take a human life, the tool is dependent on the human user. If you want to explore AI to support your writing, my key steps in creating something human are:

- Training it on my voice (the links to previous work)

- Choosing a specific, narrow purpose

- Treating the output as a smarmy first draft, something that needs medium-to-heavy editing to reach a quality I want my name on.

As I familiarize myself with Claude, the tool may be more useful, the editing lighter. But still, I worry, will it steal my work? Ruin my creativity? Or just be bland?

I asked Claude.

Here’s what you can tell writers about working with AI:

On “theft”: AI doesn’t steal your work—it’s trained on patterns from millions of texts, not copying specific pieces. Think of it like learning to write by reading widely. The real creative work—your unique perspective, experiences, and voice—can’t be replicated.

On creativity: AI is a tool, like a thesaurus or writing software. It can help break through blocks, explore new angles, or generate raw material to shape. AI can spark more creativity by giving writers something to react against or build from.

On blandness: AI output is often generic because it’s trained to be “safe.” Use AI as your first draft generator or brainstorming partner, then infuse it with your weird observations, your specific knowledge. The magic happens in the revision.

I never did run the video ads; Facebook locked me out and I’m waiting to get back in. I’m still learning how to collaborate with AI, rather than competing with it or ignoring it. As a writer, AI is an opportunity disguised as a problem. With Claude helping with mechanics—research, structural suggestions, a brainstorming partner—I’m free to do the work only a human can do: finding emotional truth and making unexpected connections. My best stories come from places AI has never been. Sometimes I want some help to get there.

________

Allison K Williams is Brevity’s Social Media Editor. Let’s talk about the magic of revision this weekend, in the virtual intensive Ultimate Revision Weekend, taught with Brevity Editor-in-Chief Dinty W. Moore. From sentence craft to story power to quick & dirty fixes, get going and get closer to published. June 21-22, $295. Find out more/register now.

Discover more from The Brevity Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Tagged: AI, artificial intelligence, chatgpt, Claude, technology, writing, writing process

.png)