When I was asked to give an impromptu five-minute speech and then to count backwards in intervals of 17 - all in front of a panel of three strangers - the acute stress was written on my face.

That is because psychologists from the University of Sussex were filming this somewhat terrifying experience for a research project that is studying stress using thermal cameras.

Stress alters the blood flow in the face, and scientists have discovered that the drop in temperature of a person's nose can be used as a measure of stress levels, and to monitor recovery.

Thermal imaging, according to the psychologists behind the study could be a "game changer" in stress research.

The experimental stress test that I subjected myself to is carefully controlled and deliberately designed to be an unpleasant surprise. I arrived at the university with no idea what I was in for.

First, I was asked to sit, relax and listen to white noise through a set of headphones.

So far, so calming.

Then, the researcher who was running the test invited a panel of three strangers into the room. They all stared at me silently as the researcher informed that I now had three minutes to prepare a five minute speech about my "dream job".

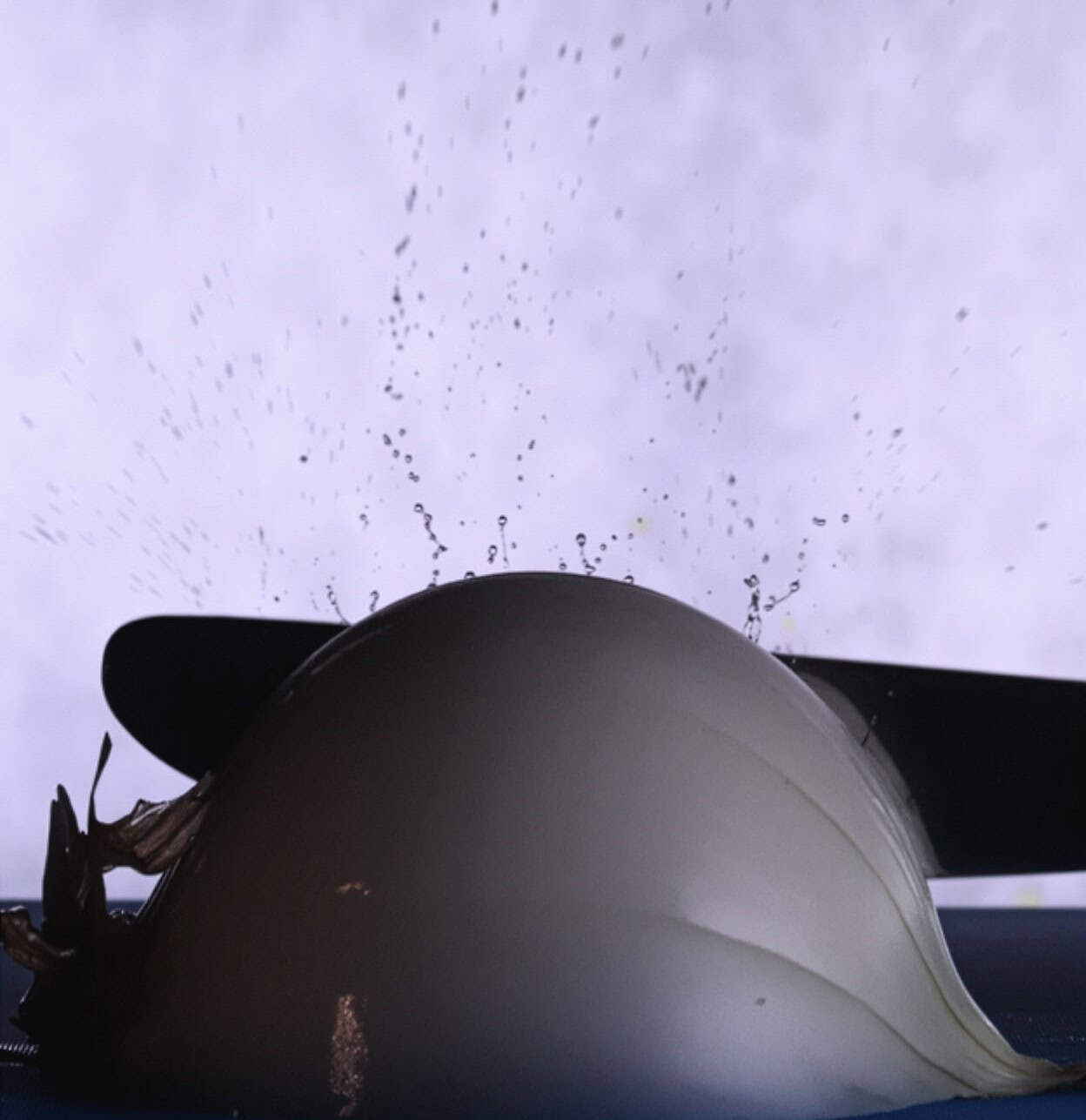

As I felt the heat rise around my neck, the scientists captured my face changing colour through their thermal camera. My nose quickly dropped in temperature - turning blue on the thermal image - as I considered how to bluster my way through this unplanned presentation. (I decided I would take the opportunity to make my pitch to join the astronaut training programme!)

The Sussex researchers have carried out this same stress test on 29 volunteers. In each, they saw their nose dip in temperature by between three and six degrees.

My nose dropped in temperature by two degrees, as my nervous system pushed blood flow away from my nose and to my eyes and ears - a physical reaction to help me to look and listen for danger.

Most participants, like me, recovered quickly; their noses warmed to pre-stressed levels within a few minutes.

Lead researcher, Prof Gillian Forrester explained that being a reporter and broadcaster has probably made me "quite habituated to being put in stressful positions".

"You are used to the camera and talking with strangers, so you're probably quite resilient to social stressors," she explained.

"But even someone like you, trained to be in stressful situations, shows a biological blood flow shift, so that suggests this 'nasal dip' is a robust marker of a changing stress state."

Stress is part of life. But this discovery, the scientists say, could be used to help manage harmful levels of stress.

"The length of time it takes someone tor recover from this nasal dip could be an objective measure of how well somebody regulates their stress," said Prof Forrester.

"If they bounce back unusually slowly, could that be a risk marker of anxiety or depression? Is it something that we can do anything about?"

Because this technique is non-invasive and measures a physical response, it could also be useful to monitor stress in babies or in people who can't communicate.

The second task in my stress assessment was, in my view, even worse than the first. I was asked to count backwards from 2023 in intervals of 17. Someone on the panel of three impassive strangers stopped me every time I made a mistake and asked me to start again.

I admit, I am bad at mental arithmetic.

As I spent an embarrassing length of time trying to force my brain to perform subtraction, all I could think was that I wanted to flee the increasingly stuffy room.

During the research, only one of the 29 volunteers for the stress test did actually ask to leave. The rest, like me, completed their tasks - presumably feeling varying degrees of humiliation - and were rewarded with another calming session of white noise through headphones at the end.

Prof Forrester will demonstrate this new thermal stress-measuring method in front of an audience at the New Scientist Live event in London on 18 October.

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of the approach is that, because thermal cameras measure a physical stress response that is innate in many primates, it can also be used in non-human apes.

The researchers are currently developing its use in sanctuaries for great apes, including chimpanzees and gorillas. They want to work out how to reduce stress and improve the wellbeing of animals that may have been rescued from traumatic circumstances.

The team has already found that showing adult chimpanzees video footage of baby chimpanzees has a calming effect. When the researchers set up a video screen close to the rescued chimps' enclosure, they saw the noses of animals that watched the footage warm up.

So, in terms of stress, watching baby animals animals playing is the opposite of a surprise job interview or an on-the-spot subtraction task.

Using thermal cameras in ape sanctuaries could prove to be valuable in helping rescued animals to adjust and settle in to a new social group and strange surroundings.

"They can't say how they're feeling and they can be quite good at masking how they're feeling," explained Marianne Paisley, a researcher from the University of Sussex who is studying great ape wellbeing.

"We've [studied] primates for the last 100 years or so to help us understand ourselves.

"Now we know so much about human mental health, so maybe we can use that and give back to them."

So perhaps my own minor scientific ordeal could contribute, in a small way, to alleviating distress in some of our primate cousins.

Additional reporting by Kate Stephens. Photography by Kevin Church

.png)