Plants that feed on meat and animal droppings have evolved at least ten times through evolutionary history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

Riley Black - Science Correspondent

June 6, 2025

:focal(1000x667:1001x668)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/99/2b995f6b-bcc3-4bed-8823-9b14e776e54a/droserawithfly_web.jpg) A Cape sundew wraps its sticky leaves around a helpless fly.

Ben pcc via Wikipedia under CC By-SA 4.0

A Cape sundew wraps its sticky leaves around a helpless fly.

Ben pcc via Wikipedia under CC By-SA 4.0

The horror can only be seen in slow motion. When a fly touches the outstretched leaves of the Cape sundew, it quickly finds itself unable to take back to the air. The insect is trapped. Goopy mucilage anchors it in place. Struggling doesn’t help. More often than not, the jerking movements to get free only bring the meal into contact with more points of sticky contact. Little by little, the leaf curls over the insect, almost as if possessive, as the digestive process begins.

It’s hard not to relate to the little insects that carnivorous plants like the Cape sundew, Venus flytraps and pitcher plants feed upon. What seems to be an inert plant, a part of the ecological background, suddenly becomes an inescapable trap. The idea has stuck with us so strongly that we have turned human-eating plants into a sci-fi staple, even though such organisms may seem to us primordial or better suited to some prehistoric moment. In fact, carnivorous plants do have a deep history that stretches back millions of years—throughout their past drawing in essential nutrients from animal prey that the soil itself does not provide.

Most of this carnivorous botany is small, but the diversity of different trapping mechanisms raises an evolutionary question. Why haven’t carnivorous plants grown to sizes large enough to rival the human-munching plants we repeatedly invoke in fiction?

Plants make their own food. We all learn this basic fact of nature early on: The biological process photosynthesis allows plants to use sunlight to fuel their own food production and make our planet green. But exceptions to every rule exist, of course, and some plants need a little more than photosynthesis or soil nutrients alone can provide. Some plants have needs that can only be met by animal sources, a requirement that plants have evolved time and again to meet over tens of millions of years.

The oldest fossils of carnivorous plants yet uncovered are more than 34 million years old, preserved in amber. “When I first put these amber inclusions under the microscope, I could not believe what I saw,” says Alexander Schmidt, a paleobotanist at the University of Göttingen in Germany who described the fossils in a 2014 study. Not only leaves, but tentacle-like projections were visible through the fossil tree resin.

The plant fossils were distinct and not attributable to any known species, but they looked extremely similar to a group of carnivorous plants that still grows along South Africa’s Western Cape called Roridula. In the living plants, sticky projections along the leaves trap insects that then attract other insects that leave their droppings on those leaves, which the plant draws nutrients from. The amber-bound leaves are so similar in form that they likely functioned the same way, trapping insects as bait that then brought in scavengers that inadvertently fed the plant.

The way Roridula and its fossil counterpart have gathered extra nutrients is not the only carnivorous trick in the botanical book. Some carnivorous plants ensnare insects and other small invertebrates, like the famous Venus flytraps of North Carolina and South Carolina’s marshes. Bumbling insects trigger botanical wisps that let the plant know when to close its trap and begin digesting the exoskeletal meals. Sundews, by contrast, are much more widespread and grow on every continent except Antarctica. Gluey glands on their leaves trap insects and produce enzymes to digest them. Pitcher plants can be more varied in how they make a living. The vase-shaped plants can feed on everything from insects lured inside the pitfall traps to the excrement of small creatures like tree shrews that leave droppings in the pitcher as they feed on the plant’s nectar. Carnivorous plants don’t come in just one form, in other words, but have evolved over and over again through time, flowering into an array of various sticky, slippery and spiky traps.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/81/e0/81e0c475-8242-48a6-a9a5-a19b171615aa/gettyimages-1233194241_web.jpg) A Venus flytrap digests its prey.

Christoph Schmidt / picture alliance via Getty Images

A Venus flytrap digests its prey.

Christoph Schmidt / picture alliance via Getty Images

Tracking the history of such plants is a challenging task. “Carnivorous plants mostly occur in swampy habitats or moist forests where the potential for fossilization is slow,” says Schmidt, often because of relatively acidic soils found in such habitats. But pollen is often more resilient than the larger plant parts that are more prone to decay.

An entire subdiscipline of paleontology, called palynology, focuses on the study of fossil pollen. Often, pollen from plants can be detected in ancient rock even when fossils of leaves, flowers and other large parts are missing. In the case of carnivorous plants, Natural History Museum, Berlin, botanist Eva-Maria Sadowski says, prehistoric relatives of today’s waterwheel plant are known from prehistoric pollen in rocks about as old as the carnivorous leaves in amber. More fossils will be needed to know if the prehistoric waterwheels grew snap traps to enclose small aquatic invertebrates, like its modern counterparts, but the lineage was already present during a time when the world was warmer and wetter, and mammals were just beginning to get big.

So far as botanists have been able to discern, Sadowski notes, carnivorous plants of one form or another have evolved at least ten times. To date, the oldest pollen records of carnivorous plant groups go back to the Eocene, which lasted between 33.9 million to 55.8 million years ago. Among the most diverse are the sundews, known to experts as Droseraceae. “The fossil record of Droseraceae is the richest of any carnivorous plant lineage,” Sadowski says, known from fossil sites in Australia, Antarctica and Central Europe.

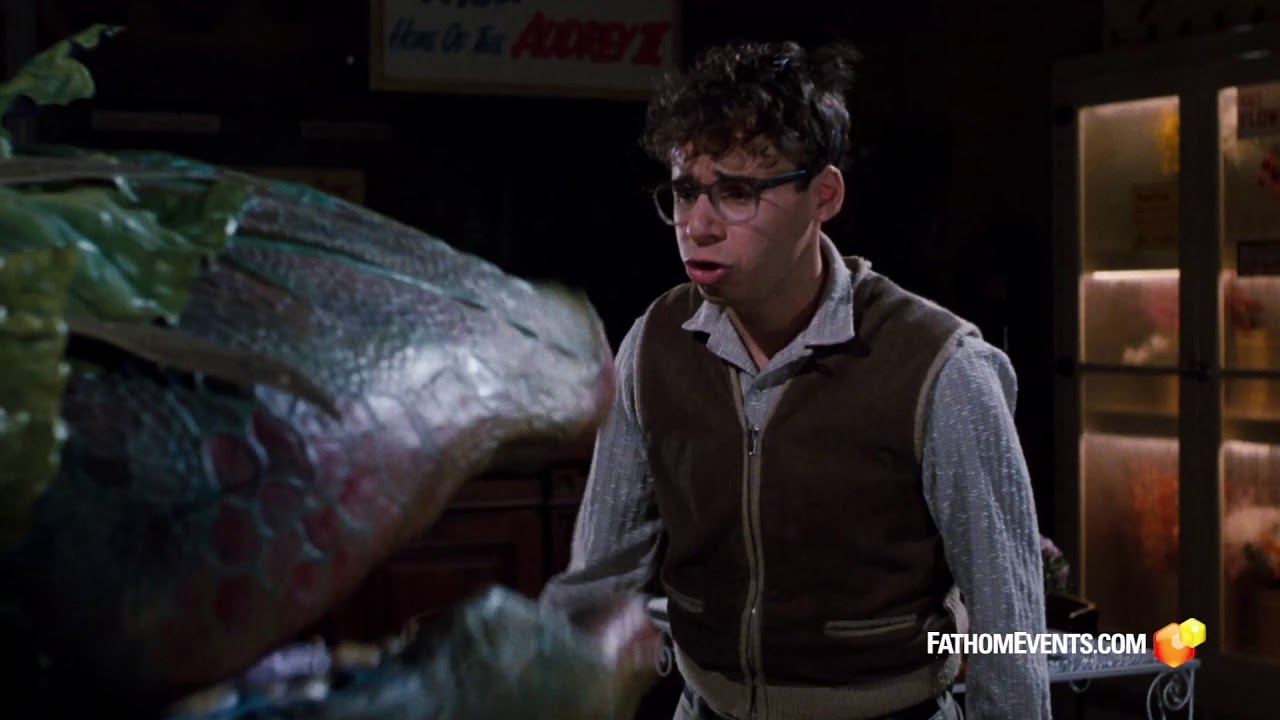

Carnivorous plants truly do have an ancient history, and given their repeated, independent evolution, even older carnivorous plant records may be found. But visions of enormous carnivorous plants capable of trapping humans, like the human-munching plants of 1960’s The Lost World or even the crooning Audrey II of Little Shop of Horrors, are entirely fictional. Some large carnivorous plants are alive out there, but none is big enough to make a meal out of you.

Little Shop of Horrors: The Director's Cut - "Feed Me, Seymour!" Clip

In terms of overall size, Schmidt says, one of the largest carnivorous plants in the world grows in western Africa. Growing as a liana, or a ropy vine, Triphyophyllum peltatum can reach more than 160 feet in length and traps insects in sticky glands that grow along it. But the plant’s carnivorous abilities only last for the early part of its life, Schmidt says, when it grows along the forest floor. And while the pitcher plant Nepenthes rajah in Borneo is large enough to trap lizards, frogs and other small vertebrates, the pitchers themselves only get to be sixteen inches deep, which is incredibly impressive for a plant but much smaller than the human-munching triffids of science fiction.

Sundews, pitcher plants, flytraps and other critter-trapping plants have done extremely well for themselves, through millions of years, ensnaring small prey and developing relationships with animals that bring nutrients the plants otherwise couldn’t access. And while larger organisms populate the world, carnivorous plants have evolved to attract and prey upon the small as a consequence of where they live.

“Carnivorous plants already grow in nutrient-poor habitats,” Sadowski says. The plants have evolved their various trapping mechanisms to feed upon animals because they are unable to get all they need from the environments they grow in. Carnivory is a workaround to be able to grow where they are. The biomechanics of a trapping mechanism strong enough to hold bigger animals aside, a larger carnivorous plant would have to grow in a habitat with better soil to get so big, in which case there wouldn’t be much reason for them to be carnivorous at all.

Eating other living things is a complicated ability to evolve for plants. While we can imagine a carnivorous cactus, for example, those sturdy plants usually grow in habitats with little water and so would lack the necessary moisture to keep producing and pumping out sticky mucilage to trap prey. And trees like redwoods or even the maple in the yard are unlikely to evolve carnivory because they already grow in soils replenished by the decay of organic matter, like leaf litter, and adding even more nutrients through prey might be too much of a good thing. Plants aren’t eating animals just for their own sakes. The adaptation is an impressive workaround that allows carnivorous plants to grow where they would otherwise struggle. Carnivorous plants have no reason to grow to horror film sizes because they are already living on adaptation’s edge, borrowing what they need from another kingdom of life as they huddle in the world’s wetlands.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

- More about:

- Biology

- Botany

- Carnivores

- Ecology

- Environment

- Insects

- Nature

- Plants

.png)

![Debt as a double-edged risk: A historical case from Nahua (Aztec) Mexico [pdf]](https://news.najib.digital/site/assets/img/broken.gif)