Note: This is an unofficial, non-commercial translation of Morris Chang’s memoir, shared for educational and entertainment purposes only. Full disclaimer below.

Gao Xijun

Leaving a record for history

Why we publish entrepreneurs’ memoirs

In the wars of the twentieth century, a nation’s fate was often led by heroes; in the peaceful times to come, the rise and fall of economies will be led by entrepreneurs.

In the foreseeable future, the global trend is moving toward peace. International competition will no longer be about the number of nuclear weapons but about economic strength. In the economic competition of the twenty-first century, we will see three characteristics: using technological research and development as the main axis of national power, reflecting the ebb and flow of national strength through competitiveness, and featuring entrepreneurs as the main actors on the global competitive stage.

From the perspective of economic history, Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) was an economist in the first half of the twentieth century who placed the greatest emphasis on “innovation” and “entrepreneurs.” He believed that “clusters of innovation” (such as the automobile) would bring about tremendous changes in lifestyles; entrepreneurs who discover investment opportunities and take on risks are the driving force behind economic growth.

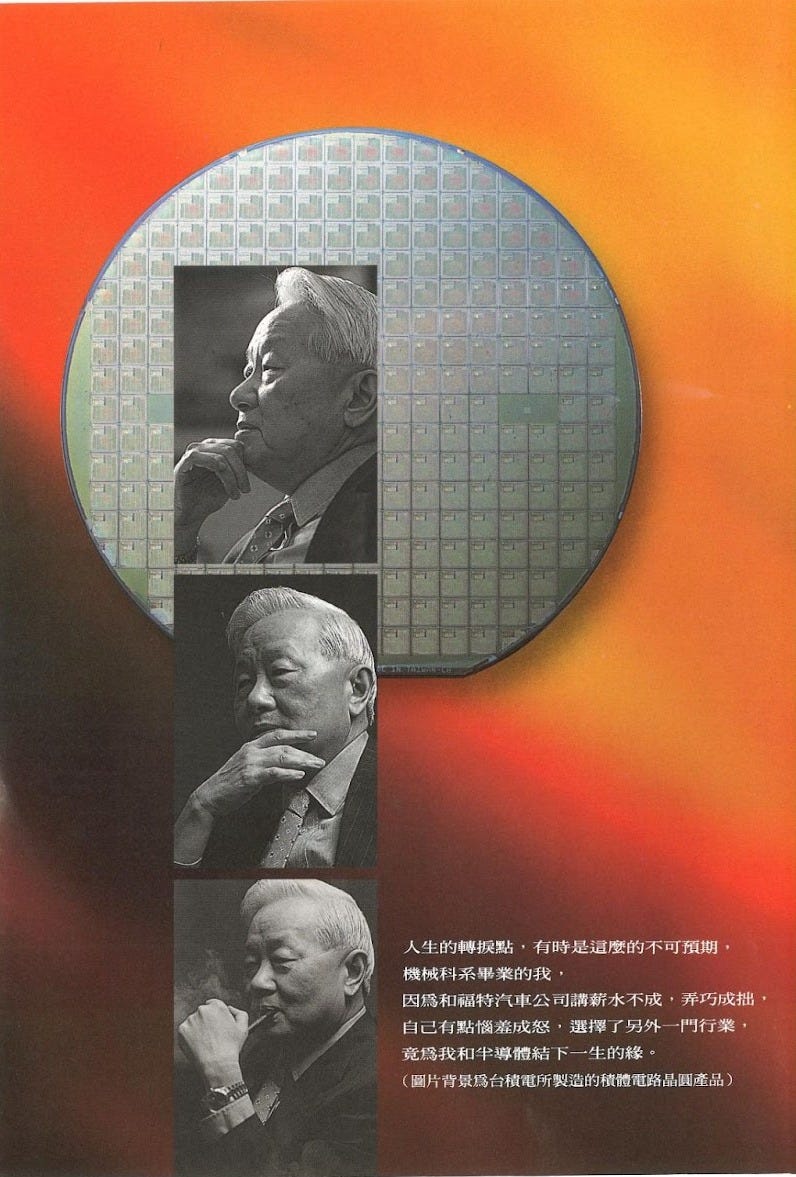

Schumpeter's words can be validated by the development of Taiwan's economy over the past half-century. Mr. Wang Yung-ching of Formosa Plastics represents the emphasis on meticulous management during the era of economic takeoff; Mr. Morris Chang of TSMC represents the grand talent and vision displayed in the high-tech era.

Commonwealth Publishing is dedicated to disseminating ideas of progress, and has successively published works related to important figures who have actively participated in Taiwan's development. These individuals are heroes and contributors in the broad sense. They either have the ambitions of heroes or the undertakings of contributors. In their collections of essays, biographies, and memoirs, these government leaders, entrepreneurs, experts, and scholars candidly and systematically recount their experiences, trajectories, successes, and failures from the perspective of historical witnesses.

The publication of this Autobiography of Morris Chang is especially rare. At the age of eighteen, Mr. Chang left war-torn China and arrived at Harvard University in Cambridge. In the long years that followed, he concentrated on studying and working in the English-speaking world. Now, he has remarkably written down his experiences in Chinese, page by page—a humanistic achievement beyond his technological world.

When reading various commentaries on Morris Chang, what impressed me most were the following two sentences:

When everyone praises his technological achievements, Morris Chang sees only responsibility.

When the world envies his brilliance in this century, Morris Chang thinks only of contribution.

Is it the ever-changing Western technology that makes him see only responsibility? Is it the subtle influence of Eastern culture that makes him think only of contribution? Perhaps readers will find the answer in his autobiography.

This autobiography has just covered half of his life. We eagerly anticipate the early publication of the second half of his autobiography.

February 1998, Taipei

Morris Chang

What a different era!

This autobiography covers the period from my birth to the age of thirty-three, exactly half my current age.

People busy with work seldom have time to reflect on the past, but in the still of the night, when I occasionally reminisce, what I miss most is not the period after thirty-three when my career had some achievements but my earlier life.

What a different era that was!

Before the age of eighteen, I had fled three times and lived in six cities (Ningbo, Nanjing, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Chongqing, Shanghai), changing schools ten times. I had experienced gunfire (Hong Kong) and bombings (Guangzhou, Chongqing), crossed battle lines (from Shanghai to Chongqing); I had an untroubled childhood (Hong Kong) and also tasted the passionate life of a middle school student during the War of Resistance (Chongqing); moreover, I experienced the sorrow of leaving home and country, not knowing when I would return (from Hong Kong to the United States).

At eighteen, I entered Harvard University in the United States. Among more than a thousand blue-eyed classmates, I was the only Chinese. In that year, I had only American friends, used only English, and absorbed Western culture like a sponge. Even now, decades later, that year at Harvard remains the most unforgettable and exciting year of my life.

At nineteen, I entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, learning skills for my livelihood at this premier institution of science and engineering.

At twenty-four, I entered the semiconductor industry, which itself was only three years old at the time.

At twenty-seven, I joined a world-class company in its golden age—Texas Instruments—drinking coffee and discussing research with Jack Kilby, the inventor of the integrated circuit, and witnessing his invention firsthand.

At thirty, I picked up my schoolbag again and went to Stanford to pursue a doctorate, strengthening my academic foundation in semiconductors under great masters.

At thirty-three, I completed my doctorate, returning to TI with hope and anticipation.

Those decades were such a different era! In China, in the United States, in the semiconductor industry—they were all “extraordinary times.”

It was my youth.

It was the youth of the semiconductor industry.

It was also the youth following the United States becoming a superpower.

Even in China, during the years of the War of Resistance, one could sense a strong youthful spirit.

My reasons for writing this autobiography: motivations from my distant and recent past

Beautiful memories alone are not enough to make me pick up the pen to write an autobiography. The decision to write still has its distant and recent causes.

The distant cause is the dream of becoming a writer in my youth. In primary school in Hong Kong and middle school in Chongqing and Shanghai, there were six or seven years during my childhood when I was obsessed with writing as a lifelong career. The dream of being a writer was dispelled before graduating from high school by my father’s casual remark: “You'll go hungry.” After high school, I went to the United States to study. In the following thirty-some years in America, not only did I rarely write in Chinese, but I even had few opportunities to read Chinese books and newspapers. More than ten years ago, I came to Taiwan and began using Chinese as my primary language again; the writer's dream of my youth became only a memory. Sometimes I ask myself, “Can I still write a long piece in Chinese?”

Until more than two years ago.

At that time, my friend Albert Yu invited me to write a preface for his new book My View of Intel (published by Commonwealth Publishing). He said, “Around two thousand words will suffice.” But after reading his manuscript, I was quite moved by the part where he wrote about Intel's history, so I spent an entire Sunday casually writing four or five thousand words. This was one of the few "long pieces" in Chinese I had written in decades, and writing it seemed to come quite naturally.

A few months later, Professor Gao Xijun, the publisher, came to see me. Professor Gao believed that in my life experiences, there must be many interesting stories that could be shared with readers in the form of an "autobiography." He also said that if I was unwilling to write it myself, I could use the method of dictation, allowing a professional writer to ghostwrite. I didn't like the dictation method because, in the past, when I read such biographies, I always felt they lacked a bit of the author's personal touch. But if I were to write it myself, what a bold and time-consuming attempt it would be! Did I have the ability and time? So I didn't give Professor Gao an answer for several weeks.

The pleasure of recollection, but the torment of writing

Just then, one evening, I was rereading my beloved collection of Hemingway's works and came across his short story "The Snows of Kilimanjaro." The protagonist is a writer who, afflicted with gangrene at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa, is immobile and waits for death while gazing at the snow-covered peak. Below are his ethereal thoughts before dying:

“Now he would never write the things that he had saved to write until he knew enough to write them well. Well, he would not have to fail at trying to write them either. Maybe you could never write them, and that was why you put them off and delayed the starting. Well he would never know, now.”

The result of procrastination turned out to be the helplessness and uncertainty at the end of life! A few days after reading this story, I accepted Professor Gao's invitation and prepared to write my autobiography myself.

I agreed, but every time I picked up the pen, I regretted it: I had agreed too rashly! For me, reminiscing is a kind of enjoyment; putting pen to paper is torment. Many nights and weekends, I sat at my desk, pen in hand, staring at a blank sheet of paper. So many emotions surged within me, but they were blocked within that short, narrow fountain pen, unable to be freely expressed on the white paper. Including the time spent gathering materials, this autobiography took me several hundred hours.

After fifty or sixty years, with so many times of fleeing and moving, there is very little material from before I was eighteen. This is regrettable because that period was when I wanted to be a writer, and I kept diaries and wrote quite a bit. But the diaries before the age of sixteen are completely gone; only a few essays remain, thanks to Chongqing Nankai Middle School, which remarkably preserved them for decades and published them in an alumni memoir a few years ago. Reading them now, although the words are immature, they evoke many memories. Among the lost writings, the most regrettable is a travelogue I wrote after trekking from Shanghai to Chongqing over fifty days; I remember my parents proudly showed it to their friends at the time.

The diaries from when I was sixteen or seventeen in Shanghai miraculously appeared at my parents' home in New York more than twenty years ago. The events before and after graduating from high school, when the Communist army was steadily approaching Shanghai, now read as if from another lifetime. There is more material from after I turned eighteen, but it's still not abundant. The most useful materials are the intermittent diaries.

The second volume will have to wait a few years

Before the first volume of the autobiography was even published, people were already asking about the second volume. To be honest, the first volume consumed so much of my energy and time, and now I'm busy laying the foundation for TSMC and WaferTech, these two companies, so in the short term, I really don't have the courage to start writing the second volume. Perhaps in a few years.

The first volume is finally completed. This has been an emotional journey—over two years, several hundred hours of intensive work, so much warmth, so much torment—and now I can finally breathe a sigh of relief. Today's mood is reminiscent of a day more than thirty years ago. That day, I passed the doctoral examination at Stanford University, breathed a big sigh of relief, and in the evening drove thirty miles to San Francisco's Chinatown for a big meal. After eating, I went to the bridge club to play my first game of bridge in half a year (see Chapter 5).

Is today the same? More than thirty years have passed me by. Today, although I have the same feelings as back then, I no longer have the same exuberance.

“We live in a Great Era”. We seldom hear this phrase now, but when I was a boy, it captured the zeitgeist.

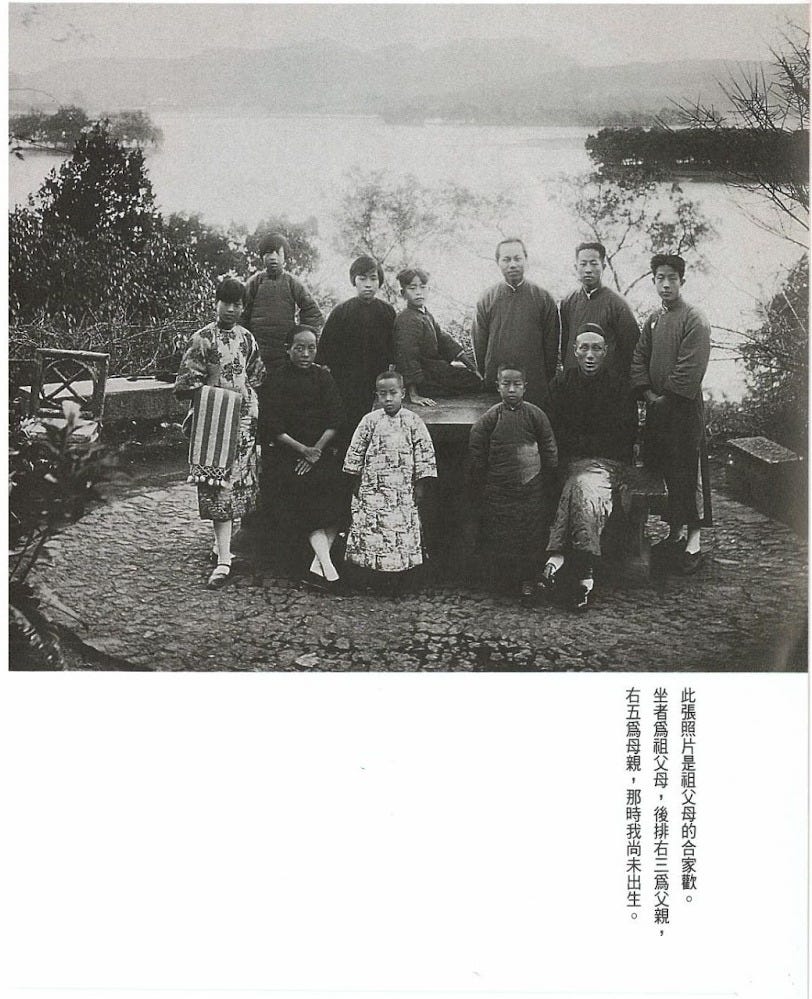

The generation of my (paternal) grandfather, Zhang Kuanfu (1885-1943), valiantly advocated for reform in spite of international humiliation. Yet, with every step forward, China seemed to take one backward. During my grandfather’s childhood, the first generation of Chinese reformers, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, championed a constitutional monarchy. In my grandfather’s teenage years, Emperor Guangxu introduced the Hundred Days’ Reform. However, Empress Dowager Cixi, ruling from “behind the curtain,” abruptly halted these reforms. When my grandfather turned twenty-five, the 1911 Xinhai Revolution ended more than two millennia of dynastic rule, ushering in the Republic of China. Yet, following Yuan Shikai's death, China descended into chaos and warlordism. Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist (Kuomintang) Northern Expedition briefly reunified China, providing a brief period of stability and progress, all to be razed when the Japanese invaded. My grandfather passed in Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The generation of my father, Zhang Weiguan (1906-1992), was the first to receive a Western-style university education. “Democracy” and “Science” became the youth’s rallying cries, and intellectuals like Hu Shih, their idols. Even into his old age, my father fondly recalled his days at Guanghua University in Shanghai, listening to Hu Shih's lectures. In his youth, my father’s heart brimmed with hope for China’s democracy, progress, and modernization. Sadly, his generation realized only dashed hopes and frustrations. The Sino-Japanese War erupted when my father was thirty-one, forcing him to endure eight years of displacement and hardship. By the war’s end, he was nearly forty and ready to embrace the stable, prosperous life he had long envisioned. Yet, these dreams were shattered with the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War.

A few years later, when China changed hands, my father had no choice but to relocate our family—my mother and me—to Hong Kong. A year after sending me to college in the US, my parents also moved to the United States.

Still in the prime of his life, my father summoned the determination to start anew. At the age of forty-five as the eldest in his class, he enrolled in Columbia University’s Business School aiming to gain a thorough understanding of American business. Yet, reality proved cruel. After receiving his MBA at the age of forty-seven, he struggled to secure suitable employment. Ultimately, he opened a small store with my mother to make ends meet, and he pinned all his hopes on me, his only child. In his twilight years, he lived comfortably, but he could not rid himself of the melancholy of being in exile in a foreign country with unfulfilled ambitions.

My mother, Xu Junwei (1910- ), was the exemplary dutiful wife and loving mother caught between two eras, old and new. In the old era, she dedicated her life wholly to my father and me; in the new era, she fervently engaged in my father’s career, joining my father in (all) his social functions.

Her love and care for me, as well as her education of me, were meticulous and thorough. Our small family comprised three: my father, my mother, and me, a very close-knit, pleasant, and sweet household. My mother (often) acted as the peacemaker. When my father was distressed or frustrated, she would ease his hardships with the warmth of our home; when I made mistakes, she would gently steer me; and when my father scolded me and I, being young and immature, felt rebellious, she was the ultimate arbiter.

In 1931, I was born in Ningbo, my hometown. My father was the Director of the Finance Bureau of the Ningbo County Government. It might sound like a significant position, but at the time, Ningbo was rather underdeveloped and (unimportant), and most ambitious people hoped to work in big cities like Shanghai, Nanjing, or Beijing.. When I had just turned one, my father took a deputy manager position at a bank in Nanjing, and my mother and I followed. When I was five, my father was promoted to be a bank manager in Guangzhou, so naturally we joined him. We lived in Guangzhou for only half a year when the Marco Polo Bridge incident occurred, and Japanese planes began their Guangzhou bombing campaign. In response, my mother and I fled first to nearby Hong Kong. The following year, when Guangzhou fell into enemy hands, my father also fled to Hong Kong and was appointed a local branch manager.

We breathed in Hong Kong from 1937 to 1942 (age six to eleven). At that time, less than a million people resided in Hong Kong; the city’s beauty and cleanliness shone. When the flames of war swept across the country, turning large swaths of land into occupied territories, Hong Kong was a safe haven.

I have very fond memories from that period of my childhood. Our family first lived on Hong Kong Island, then we moved to Kowloon, living in a very comfortable apartment. From second grade to fifth grade, I attended Pui Ying Primary School, and in sixth grade, I went to Pui Ching Middle School.

Both schools were within walking distance, so I trekked to school by myself. We often went on outings on Sundays, and my favorite places to visit were Victoria Peak and Repulse Bay. In recent years, I often return to Victoria Peak and Repulse Bay, and every time I go back, memories of my childhood reappear before my eyes. The road that circles Victoria Peak now is still the same as before (of course, after many repairs). In my days, there were scarcely any tourists, and today’s city vista would be unrecognizable. Back then, the tallest building in Hong Kong was the HSBC building by the harbor, a dozen or so stories high; now, skyscrapers are commonplace in Hong Kong, and the old HSBC building has long been demolished. If it were still there now, it would be indiscernible. As for Repulse Bay, the throng of tourists have overrun the Bay leaving it crowded and noisy, the tranquil charm it once had now lost to time.

When I was young, I was not in good health. Although I avoided major illnesses, I often caught colds and had fevers. My mother worried incessantly for years, giving me cod liver oil to take every day, and often stewing chicken soup for me, hoping to strengthen me. Later, when I entered middle school, my health gradually became robust. When I was in primary school, because I had no brothers or sisters at home and rarely played ball or games with my classmates on the playground, I often stayed at home alone. My mother bought countless books for me to read. I remember that at that time, the Commercial Press published a set called “Children’s Library,” which my mother bought and filled a bookshelf with. It included novels like Water Margin, Journey to the West, and Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Before I graduated from primary school, I had read the entire “Children’s Library.” This reading habit cultivated from a young age has persisted throughout my life.

The year I turned ten, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor sealed the outbreak of a Second World War. Pearl Harbor marked a watershed for my childhood mind. My memories before Pearl Harbor are cloudy, but after are crystal clear. Hours after Japan’s sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, they immediately attacked Hong Kong. At daybreak on December 8, 1941, we heard the sound of bombs overhead. However, I had an exam that day, so I still trudged to school. When I arrived, I began to understand the crisis and learned that the Japanese were already attacking Kowloon. Of course, the exam was not held, nor were any classes, so I rushed home. Although we lived in a relatively quiet area, my father deemed it safer to relocate to a hotel, so that same day, the three of us, along with a maid, moved to the Kowloon Hotel (behind today’s Peninsula Hotel).

Three days later, Kowloon fell to the Japanese army. Hong Kong withstood for another dozen days but the British troops surrendered on Christmas Eve. From when Japan began its attack on December 8 until the end of the month, we hid in the Kowloon Hotel. Though we were fortunately all safe, we were not spared the terror. It started with the rumble of bombs, then routine gunshots in the streets, and later the incessant sounds of artillery as the Japanese bombarded Hong Kong from across the sea.

During those weeks, the city was almost entirely under martial law; we could not, and did not want to, leave the hotel. As food in the hotel gradually ran out, we began eating canned food, and in the end, even the canned food was almost depleted. Fortunately, by then, martial law was lifted. My parents returned home to find that during the interim period when the British troops had already withdrawn and the Japanese troops had not yet occupied Kowloon, our home had been looted by bandits. The relatives staying at our home and the maid who remained at home were all thoroughly shaken.

We lived another full year in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. During that year, life in the city gradually regained some semblance of order. I completed primary school; my father continued working at the same bank. Signs of the Japanese occupation were visible everywhere. Armed “Imperial troops” stood guard at all major intersections, and every passerby was compelled to bow in their presence. My primary school abruptly produced several staunchly pro-Japanese teachers who, whenever the chance arose, would lecture us on how British and American soldiers were only good at drinking and revelling, and how the moment they heard gunfire, they would instantly retreat in panic. My father’s position under the new regime proved even more difficult and his feelings unspeakable. Thus, at the end of 1942, he decided that our family would relocate to Chongqing. At the time, Chongqing served as the provisional capital of the Republic of China—what people called the “accompanying capital”—and the most important city in Free China. Before departing, my father resolved to first pass through Shanghai and Ningbo to pay our respects to my paternal and maternal grandparents.

At the end of 1942, we traveled by ship to Shanghai, stopping over for about three months. We celebrated the Lunar New Year for a few weeks in our hometown Ningbo.

For an eleven-year-old boy like me, those three months in Shanghai were thrilling. We gathered with relatives I had not seen in years, many of whom had receded into the haze of distant memory. I also experienced, for the very first time, China’s most cosmopolitan and prosperous city. During those three months, my father resolutely prepared for our journey to Chongqing. Although many friends and family members had already fled the occupied territories for Free China, crossing the front lines was fraught with uncertainty and peril. The route would lead through remote areas with poor transportation, and war-time scarcity made everything—from basic supplies to reliable information—difficult. In retrospect, I see that my father’s decision to undertake this risky journey reflected not only boldness but also a fervent desire to return to the bosom of our motherland. At the time, both my parents were in their thirties, the age of utmost audacity.

In late March 1943, we finally departed Shanghai. When we set out, all we had was a rough outline of the route. How long would the entire trip take? What modes of transport would we use? Where would we lodge along the way? We relied only on the imperfect and uncertain intelligence my father had painstakingly gathered. The first leg was the most well defined: take a train to Nanjing, then transfer to another train to Xuzhou. Xuzhou lay in Japanese hands, but remained very close to the battle grounds where Chinese and Japanese forces fought. Once past Xuzhou, our goal was Luoyang, which was under Nationalist control. Thus, from Xuzhou to Luoyang we would have to cross the front lines.

From Xuzhou to Luoyang, we resorted to every conceivable form of transportation. When we could board trucks, we boarded trucks. When rickshaws or pedicabs were available, we clambered on. If there were no vehicles, we simply walked. While crossing the front lines, we naturally chose zones free of active fighting, yet there was never a guarantee that a sudden burst of gunfire or artillery would not erupt. We covered that portion entirely on foot. The journey from Xuzhou to Luoyang took several days. Each night, we sought shelter in humble inns, small shops, or even temples. Near the front lines, soldiers frequently conducted inspections of travelers. I recall that one night, the patrol turned out to be Nationalist troops. For the first time since we had left Shanghai, a smile emerged on my parents’ faces!Luoyang, an ancient capital, was the first major city we reached in Free China. We rested there for several days and took the opportunity to visit historic sites. There was a railway line from Luoyang to Xi’an, our next stop, but even that route harbored danger. As the train passed through Tongguan, the Japanese artillery positions lay directly across the Yellow

River. We heard that several times a month, the Japanese would shell passing trains. To minimize losses, the railway bureau deliberately assigned its oldest, most expendable trains to run this section, so that if a train were destroyed, the material damage would be less severe. This train earned the grim nickname “breakthrough train”, and always operated under cover of darkness. I remember the night we boarded that “breakthrough train.” When we reached the danger zone, the train suddenly accelerated, and all lights were extinguished. Though the carriage was packed, no one dared utter a sound. In that heavy silence, the only thing we heard was the feverish clatter of the iron wheels racing onward. After a while, the train gradually slowed, and the lights came on again. Knowing the danger had passed, everyone cheered in high spirits.

From Luoyang to Xi’an, we cut across the Yellow River plains. As a boy, my strongest impression was that after only a short while outdoors, one’s face and clothing would be covered with a fine layer of yellow dust. For countless dynasties, these plains had served as the fertile grounds to start ones empire, a vast battlefield where armed forces and horses galloped, and where kingdoms rose and fell. By then, I had familiarized myself with some history, and while gazing out the train window, I often felt a surge of historical reverie.

In Xi’an, we stayed at the Xijing Hostel. Compared to our lodgings since leaving Shanghai, this was considerably more comfortable. Xi’an abounded with historic sites. We ventured to the nearby Huaqing Hot Springs to retrace the footsteps of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang and his beloved Consort Yang Guifei from a thousand years before. We visited the site of the 1936 Xi’an Incident whose memory was still fresh amongst the populace. We rested in Xi’an for several days.

Westward from Xi’an lay our next destination, Chengdu. As no railway connected Xi’an and Chengdu, we resorted to freight trucks. In theory, freight trucks carried no passengers, but drivers profited illicitly by “catching yellow fish,” essentially smuggling travelers. Passengers perched atop cargo in the open air, jostled unmercifully as the truck navigated narrow, precipitous roads. If one did not hold tight to the ropes binding the freight, one might indeed be flung off the truck. On that harrowing route from Xi’an to Chengdu, I began to truly understand the old saying, “The road to Shu is harder than climbing to the blue sky.” And yet, despite the peril, the mountainous scenery was magnificently grand.

Chengdu, once the capital of the ancient state of Shu, delighted a young boy enamored by The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. From Chengdu to Chongqing, we finally took a public bus. By then, we were near our final destination, and our excitement palpable.

We journeyed from Shanghai to Chongqing for more than fifty days. It was grueling, wholly devoid of reliable transportation and comfortable accommodations, save for a few major cities. Yet at last, we reached Free China from enemy-occupied territories. Nothing can describe the thrill and relief we felt in that moment. As I write this now, I cannot help but compare that voyage to modern travel. Today, every moment of a journey is planned in advance; transportation and lodging are fully organized, and we demand the utmost comfort and even luxury. Quite the difference between heaven and earth! Over the decades of my life, I have traveled countless miles—millions, perhaps—and no matter how comfortable or extravagant my travels in recent years have been, the one journey that I recall most fondly, that holds the deepest significance and the most indelible impression, remains that long trek I undertook at the age of eleven, from Shanghai to Chongqing. Perhaps this is why that era is rightly called “The Great Era”?

This is an unofficial translation of the memoir of Morris Chang. It is a non-commercial, unaffiliated work intended solely for educational and entertainment purposes.

All rights to the original text and its contents are fully retained by the original author and copyright holders. This translation has not been authorized, approved, or endorsed by Morris Chang, his representatives, or any affiliated publishers.

This content should not be relied upon for scholarly or commercial use, and no part of this translation may be reproduced, redistributed, or sold. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns, please contact me directly.

.png)