If Mississippi’s remarkable success in childhood literacy tells the world one thing, it is that you don’t need to “see” pictures to learn how to read.

As someone with aphantasia – the inability to call up visual images – I could have told you that. I and hundreds of millions of others around the world with no “mind’s eye” have learned to read without visualization. I’m not talking about pictures next to words, illustrations that help visualization. Illustrations improve comprehension and can be helpful for increasing vocabulary. I’m talking about the pervasive model of teaching children to read by asking them to create pictures in their mind, which a measurable percent of the population cannot do.

The literacy community seems not to have heard of aphantasia. The term was coined only in 2015, by the neuroscientist Adam Zeman. The percentage of the population with aphantasia is small (perhaps 4%) but the capacity for internal visualization is on a spectrum. Even among the majority of people who can visualize, some imagine far more vividly than others. This discovery ought to end the assumption of “normal” visualization in the people around us.

The stakes are higher in the AI-large language model (LLM) era. LLMs generate text through pure pattern-matching, predicting the next word based on statistical relationships between words (tokens, signifiers). Students who learn to read by understanding that language is code, a system of logical relationships between symbols, who can analyze language as structure, will be better prepared to live in an AI-saturated world. Mississippi students may be even further ahead understanding language as a decodable system.

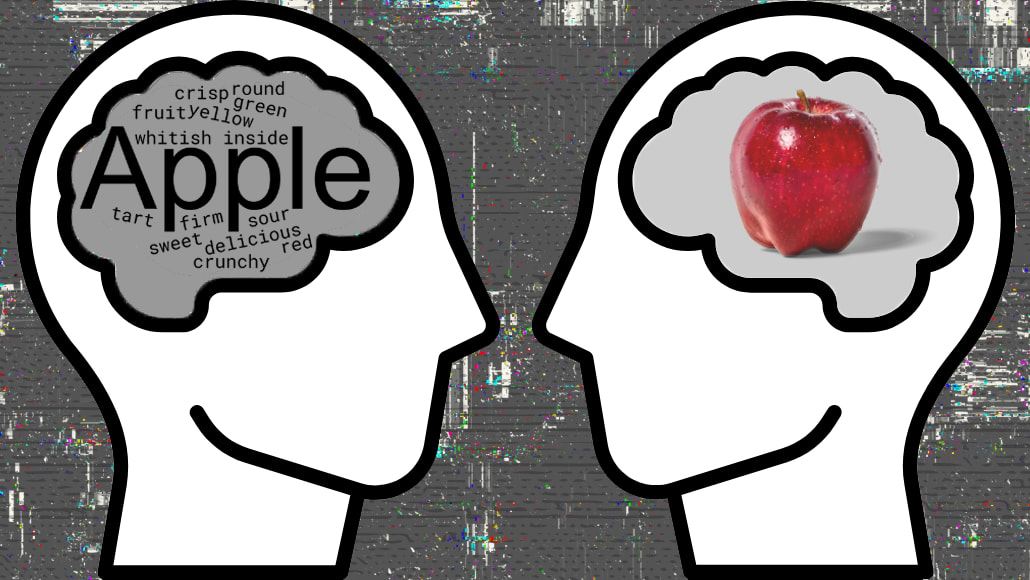

I’ve written about how, with aphantasia, I can tell LLM-produced writing. For me, language isn’t a signifier that “points to” an image of the thing or concept signified; the signifier “is” the signified. My mind does not see images but only the logical and structural patterns of language. I was floored to learn how children are taught to read in ways that will put them at a disadvantage in the AI era.

What the Science Actually Shows

Long before the discovery of aphantasia, scientific models described reading in computational terms. The most influential is the Simple View of Reading (SVR), which proposes the formula: Reading Comprehension (RC) = Decoding (D) x Language Comprehension (LC). Reading involves both the ability to translate written symbols into words (Decoding) and the ability to understand the meaning of those words (Language Comprehension). There is no variable for imagery.

More complex models, like the Dual-Route Cascaded (DRC) model, describe reading as the processing of information through distinct cognitive pathways for recognizing known words and sounding out new ones. These models explain reading as the manipulation of symbolic information – orthographic, phonological, and semantic – entirely independent of any subjective visual experience. You see what is on the page but “visualizing” isn’t part of the process.

Brain imaging studies confirm this. When children aged 5-7 are reading, their brains are overwhelmingly focused on the task of coordinating visual word recognition with phonological processing. The cognitive load of decoding, mapping letters to sounds, leaves little room for creating mental pictures at all. Telling these young readers to “make a picture in your head” runs counter to the primary work their brains are trying to do. Young children show visualization activity when listening to stories, when there is no burden of decoding. When actually reading, visualization isn’t happening.

The longstanding “reading wars” between phonics and “whole language” were debates about meaning-making (understanding the signified) versus systematic decoding (understanding the signifier). Whole language advocates and “balanced literacy” proponents prioritize holistic meaning-making, encouraging children to guess words from context using the now increasingly banned “three-cueing system.” Phonics, by contrast, teaches the logical, predictable relationships between letters (graphemes) and sounds (phonemes). It is all about understanding how letters on the page come to signify something. It is a code-based, analytical methodology.

As a young child with aphantasia (though I did not know then I had this condition). I’m not sure I could have learned any other way. For me, decoding written symbols into linguistic meaning is the whole of comprehension. There’s no second step of converting that meaning into mental pictures.

Mississippi’s Validation

Mississippi’s success was a result a statewide embrace of Science of Reading propelled by the 2013 Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA), which created a comprehensive framework that included:

Early Screening and Intervention

An End to Social Promotion

Investment in Teacher Training, particularly $millions in the Language Essentials for Teaching Reading and Spelling (LETRS) program, an intensive training that provided K-3 educators with a deep understanding of the five essential components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Deployment of literacy coaches to its lowest-performing schools and required that all teacher preparation programs ground their literacy coursework in the science of reading.

In 2013, Mississippi ranked 49th in the nation for 4th-grade reading. By 2024, Mississippi outscored the national average for the first time, ranking 9th overall and, when adjusted for demographics, the state’s 4th graders scored highest in the nation in reading.

The state’s curriculum leans heavily on phonics and language structure. Visualization appears nowhere as a foundational strategy. Mississippi shows that what works for the aphantasic mind works for all students.

The Orphaned Practice

Yet demands to visualize still dominate early childhood reading education, judging by course materials found everywhere. Visualization is put forward as a universal norm for unlocking meaning, even at the college level. The link between picturing and comprehension is treated as causal; one guide for teachers states, “if students report seeing images that do not match the text, they have probably misread something.” Visualizing is understood as foundational for almost all other comprehension skills. The instructions are direct: “When you read a text you create in your mind’s eye a representation of your reading: see, for example, the clothes characters are wearing, the expressions on the faces of the characters.” One influential remedial program sees visualization as a prerequisite for comprehension. Children fail because of “weak concept imagery.”

It is painful reading these guides, seeing how the “lack” of visual imagination is pathologized as a weakness in comprehension.

Curiously, the cognitive scientists who study reading acquisition never included visualization in their models. The whole-language advocates who once championed meaning-based instruction have stopped defending it in academic debates. Yet it thrives in classrooms everywhere, in teacher training programs, in daily lesson plans, on thousands of Teachers Pay Teachers resources, in charts on classroom walls. It exists as folklore, passed from teacher to teacher, defended by neither camp.

Perhaps the ubiquity of generative AI will finally close the gap between science and classroom practice. Visualization pedagogy teaches students to evaluate reading by whether it prompts mental imagery. Phonics teaches them to evaluate reading by whether they can decode the structure. Only the second skill lets you detect when language is operating as pure pattern, disconnected from experience or observation, which is what LLMs generate.

Why It Persisted

Visualization took hold because most people can visualize. It is natural and automatic. This intuitive feeling that good reading is an immersive event created a common-sense foundation for teaching it as a strategy.

In the mid 20th century, Louise Rosenblatt introduced the transactional theory, which distinguished between the efferent stance (reading for information) and the aesthetic stance (reading for sensory and emotional experience). The aesthetic stance invited the reader to “actively involve all five senses,” particularly when reading literature. Then along came Dual-Coding Theory (DCT) and theories of embodied cognition, developed by Allan Paivio in 1971, theorizing that our brains process and store information both in a verbal system for language and a non-verbal (or imagery) system for images. Encoding information in both channels creates “stronger, more accessible memories,” is the argument. It seemed like a compelling “scientific” rationale for visualization at the time.

The idea that visualization transforms words into “experiences” could be sold as an “adventure” rather than a chore. You see this everywhere. Culture ties pictures and memory together; the idea is deeply ingrained. Research has shown that humans remember pictures more easily than words. Early 21st century scholarship doubled down on the idea that imagination is explicitly visual and that the reader “envisions” things, even things or events not present, never experienced, or wholly fictional.

More recent theories of embodied cognition argue that language comprehension involves a “mental simulation” of the events being described, using the same neural systems involved in perception and action. According to this view, to truly understand a text, a reader constructs a “situation model,” a mental representation of the state of affairs described. You “must” see it in your head. And all this goes back to Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s concept of the “esemplastic imagination,” the idea that the mind images, ideas, and emotions and fuses them into a unified, coherent internal vision.

All in all, the intuitive feeling that reading is seeing, the scientific theory that seeing aids memory, and the philosophical ideal that true reading is a sensory experience combined to entrench a belief that visualization = deep comprehension. Teaching materials began touting visualization as evidence of comprehension. Theories provided intellectual cover for what felt intuitively right to teachers. So visualization practice remains in the classroom even while I assume early childhood educators are using ChatGPT like everyone else.

Why It Still Persists

The educational materials market (~$280 billion globally) is slow to change. A teacher trained in the 1990s trains teachers in the 2000s who create materials sold on Teachers Pay Teachers in the 2010s to teachers trained in the 2020s. The cycle perpetuates because questioning visualization would require examining the gap between research and practice, and that gap is wider than anyone wants to acknowledge. Education schools continue teaching visualization because their faculty learned it. Publishers continue selling it because teachers continue buying it. Nobody notices that visualization appears in neither the phonics advocates’ models nor the whole language defenders’ rebuttals. The fact that it appears in neither side’s academic arguments becomes irrelevant to its classroom survival.

It is unclear why data on the developing brain has been disregarded, when the evidence from neuroscience shows that for young readers, the primary task is decoding, not visualizing. The evidence from cognitive psychology shows that even for proficient readers, visualization is just one pathway to comprehension.

Students with aphantasia or weak visual imagery ability who process language non-visually – all the tens of millions of struggling readers diagnosed with “weak concept imagery” – will remain invisible because the harm is diffuse and the practice is ubiquitous. No one is systematically tracking which students fail because they’re being taught to do something their brains don’t do.

What Comes Next

The success of those of us with aphantasia demonstrates that one can learn to read without pictures, without a visual imagination. The Science of Reading’s systematic phonics and emphasis on language structure demonstrate that reading without pictures works. Mississippi shows it works for everyone.

Early childhood reading instruction needs to catch up to the world children are entering. Teaching decoding as code-breaking (graphemes mapping to phonemes through systematic rules, meaning emerging from structural relationships between symbols) prepares children for a world where language can be generated through pure pattern-matching.

Early training matters decades later. Most adults navigating AI-generated text lack the skills to detect when language operates as pattern without grounding. You can’t easily develop those skills at thirty if you learned at six that reading means making mental movies. The aphantasic reading style, the Mississippi approach, the Science of Reading all teach the same thing: language is code. Learn to break it early.

.png)

![A Rational Design Process: How and Why to Fake It (1986) [pdf]](https://news.najib.digital/site/assets/img/broken.gif)