The CHALLENGE trial tested cancer outcomes from a structured exercise program. NEJM published the study, more than a 100 news sites covered it, and hundreds reposted it on social media.

So you know the results were positive. Hugely positive, in fact. And who, I ask, does not love the story that exercise vanquishes cancer?

Sensible Medicine is a place to get the real story. This is a classic case when you have to let go of your love of great stories to see the details.

The Trial:

The stimulus to study structured exercise comes from observational studies that report associations between exercise and better cancer outcomes as well as preclinical studies that have (weakly) suggested that exercise may reduce the growth of cancer, possibly via metabolic or immune mechanisms.

CHALLENGE authors decided to test the effects of a structured exercise program in patients with colon cancer who had completed adjuvant chemotherapy. Eligibility for the trial required not dying from colon cancer, completing chemotherapy and having a functional capacity good enough to complete exercise tests.

Slightly more than 900 patients were then randomized to either general health recommendations or the structured program, which was intense. It included 17 “evidence-based techniques” for behavior change, including frequent mandatory in-person behavioral-support sessions and supervised exercise sessions. Emphasis on mandatory and in-person.

During the second 6 months, patients had more of the same but could have some sessions via phone. During the last 2 years, patients attended 24 mandatory monthly in-person or remote behavioral-support sessions combined with a supervised exercise session. The supplement took 50 pages to describe the many details of the structured exercise program.

The primary endpoint was disease-free survival, which sounds simple but was actually composite of many things: freedom from recurrent colon cancer, new primary colon cancer, a second primary cancer or death from any cause.

The results were amazing.

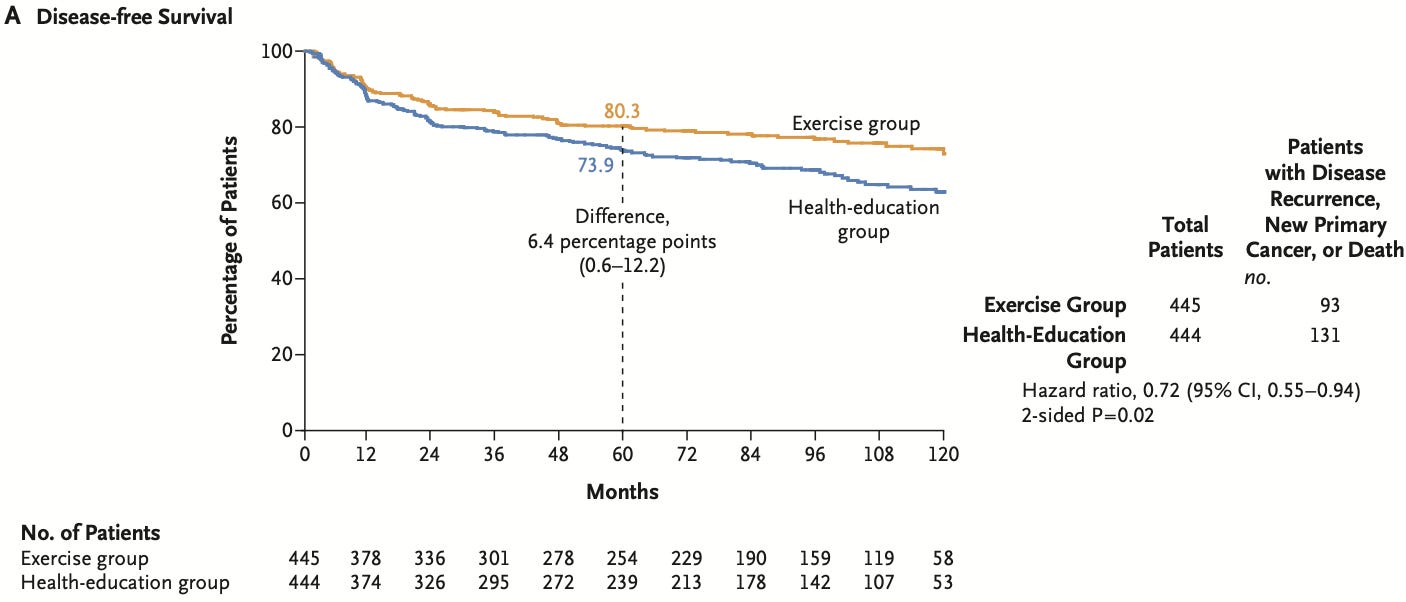

At a median follow-up of nearly 8 years, the primary outcome of disease-free survival occurred in 21% of those in the exercise group vs 29.5% of those in the health education group. The relative risk reduction was 28% with a hazard ratio of 0.72 and 95% confidence intervals of 0.55-0.94 and a p-value of 0.02.

The 5-year disease-free survival was 80.3% in the exercise group and 73.9% in the health-education group (difference, 6.4 percentage points; 95% CI, 0.6 to 12.2).

Drivers of the primary endpoint included both recurrent cancer and overall survival.

In fact, the relative risk reduction for overall death of 37% (HR 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.94) was even larger than the risk reduction in the composite endpoint.

Remarkable was that exercise also seemed to reduce recurrent colon cancer (65 vs 81 patients) as well as new primary cancers (23 vs 42 patients).

The authors concluded that this 3-year structured exercise program “resulted in significantly longer disease-free survival and “findings consistent with longer overall survival.”

The first thing to say is that I love exercise—in my personal life and as a cardiologist. I also appreciate the authors’ attempt to study exercise in rigorous RCT fashion.

While I want this story to be true, there are at least seven reasons to be cautious. These are mostly internal validity concerns. But there are also major external validity issues as well.

First, before looking at the methods, the 37% reduction in all-cause mortality is implausible and rivals many proven cancer therapies. For example, this is similar to the mortality reduction with Trastuzumab (Herceptin) in HER2+ breast cancer—a revolutionary finding.

Second, if you posit exercise provides a massive mortality benefit, there should be some effects of exercise. CHALLENGE reported almost no between-group differences in typical exercise parameters. There was zero differences in body weight, waist circumference and a mere 30 meters longer distance in the 6-minute walk test.

Third, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for disease-free survival begin separating at 12 months while the death curves take 4 years to separate. I am not a cancer doctor, but a tiny difference in exercise dose (as evidenced by the lack of objective measures) is not enough to reduce cancer recurrences that rapidly. This finding suggests suboptimal randomization, which is not surprising given the fact the ambitious complicated trial took 15 years to enroll.

Fourth, poor adherence to the exercise regimen further reduces plausibility. Nearly half of the patients in the exercise program did not complete the treadmill protocol at three years and a third did not complete the 6-minute walk test. These patients were included in the intention-to-treat findings—and would have the effect of reducing between-group differences in exercise.

Fifth, the authors originally designed the trial to detect differences at 3 years. This required 380 events to have sufficient statistical power. Due to slow recruitment and a slower-than-expected event rate they changed to a five-year analysis. Yet they still had far less than the expected primary endpoint events (224 vs 380). This reduces statistical power and raises the possibility of false positive findings—which is consistent with the biological implausibility. What’s more, the KM curves show most of their separation after 3 years. A stronger paper would have included the pre-specified 3-year results, which may have been non-significant.

Sixth, while the first five concerns relate to the conduct and the design of the trial, there is also the inherent challenge of strategy trials: different attention in the two groups. In CHALLENGE, the structured exercise group received an incredible amount of intervention in both behavioral modification and exercise. This makes performance bias highly likely, as evidenced by the large differences in the quality of life questionnaires.

Seventh, there are serious challenges in external validity or generalizability of the CHALLENGE trial. The difficulty in enrolling patients (it took 15 years) speaks to the complexity and intensity of the behavioral and exercise program. The authors don’t tell us how many were screened to enroll these 900 patients. I suspect it was a lot. What’s more, enrolled patients were young (age 61) non-obese and performed well on baseline measures of function. Even if you accepted the results as presented it would apply to a fraction of patients with colon cancer.

The cost and healthcare system implications of accepting this protocol would be massive. In the same way that regulatory trials for drugs or devices require multiple positive trials, we should feel the same about CHALLENGE.

It was a great effort. The story is delightful. But liking the conclusion is not a reason to stop thinking.

SInce this trial had such a great response on social and regular media, I will keep this column open to all. No paywall. Yet please consider supporting Sensible Medicine for its role in non-industry-conflicted critical appraisal of medical evidence. JMM

.png)