Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’d like to sign up to receive issues over email, you can do so here. This piece is written by antitrust attorney and researcher Basel Musharbash.

The biggest failure of the last administration — and arguably the primary reason that voters “threw the bums out” and put Trump in office — was the cost of housing. The price of a house jumped by about 50% during Biden’s term, and spiking interest rates meant that the effective cost of buying a home more than doubled. Rents skyrocketed as well, jumping more than 26% over those four years. Since owning a home is an iconic part of what it means to be an American, the fact that this milestone has become woefully out of reach for most people in this country has had a massively disillusioning effect on our society.

Against this background, it’s not surprising that, since the collapse of the Democratic Party in the 2024 elections, a bitter fight has broken out among Democratic insiders about — you guessed it — housing policy. The New York Times podcaster Ezra Klein and the Atlantic writer Derek Thompson have led the debate, making a series of claims about housing policy in their new book Abundance and during its publicity tour this past Spring. Specifically, they observed that construction in Texas is cheaper than in California, and that several blue states have particularly bad housing shortages. Based on that, they concluded that interest-group liberalism must inherently cause housing production (and the building of things generally) to sputter and stagnate. Government bureaucracy, labor and environmental constraints, local zoning and other rules supported by homeowners, they posited, are what is fettering the housing supply and raising housing costs in America — fueling the social and economic malaise we’re living in.

But is this argument correct? I’m sympathetic to the importance of reforming local zoning and building codes. They are, for the most part, copypasta borrowed from “model legislation” promulgated by an insurer-aligned group called the International Code Council, often with limited consideration for local realities. They impose design requirements that aren’t backed by much evidence but make it difficult (and sometimes near-impossible) for small and midsize building projects to pencil out. They give local boards discretionary authority to hold up or deny projects, which they often use to impose unreasonable impact fees on new development. And they often require developers to wait months, if not years, for bureaucratic approvals — delays that large investor-backed developers can endure easily but small developers often find ruinous.

As I told a group of rural policymakers and advocates at a conference in 2022: To build community wealth, cities large and small need to abandon the model of economic development predicated on trying to attract outside capital and industry through tax incentives and restrictive land-use codes — and instead adopt programs and regulations aimed at cultivating their ecosystems of local developers, local businesses, local capital, and local workers from the inside out. In other words, I’ve been about reforming local codes for years, long before the current argument bubbled up.

But are local land use regulations really the main cause of the housing crisis? Last August, BIG published a macro-level piece on the consolidation of homebuilders at a national scale, tracing its relationship to the precipitous drop in single-family home construction since the Great Financial Crisis and taking us back to the tradition of land reform propounded by anti-monopolist Henry George. In this article, I’m going in the opposite direction — down to the micro-level. I’m doing a deep dive into homebuilding and housing costs in the city that the Abundance crowd implies everyone else should copy: the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex (DFW).

Until recently, Dallas was one of the last few growing cities in America where a middle-class family could still afford to buy a house. It’s a good place to look at the problem. Since the 2000s, DFW has gotten lucky, avoiding the boom in home prices associated with the Great Financial Crisis, as well as the bust that followed. It has also had relatively light regulations — none of that stifling bureaucracy that Klein and Thompson disdain — as well as relatively cheap land and lots of eager homebuyers. With all of these things going for it, DFW seems like it should be a nirvana of low rents and affordable houses. But that’s not what I found. Instead, I discovered that pretty much the same dynamics afflicting blue states are also afflicting red ones — a fact that should have important implications for how we think about housing politics and policy in this country.

Let’s dive in.

It’s hard to find a more American place than Texas, and nowhere says Texas more than Dallas. Dallas was one of the most popular soap operas in 1980s America, the Dallas Cowboys are known as “America’s Team,” and the city is home to a whole slew of American business titans, including American Airlines, AT&T, and Texas Instruments. Alongside its culture and prosperity, however, what long made Dallas feel like the epitome of Americana is that it was also a place where homeownership stayed attainable — even after the 2008 financial crisis.

In 2011, the median home price in DFW was $149,900, and the income of the median DFW household was roughly double the income required to qualify for a mortgage to buy a median-priced house. That’s good enough on its own, but the median ratios actually understate how affordable the DFW metroplex was in the early 2010s. If we dig into the data, we find that lots of houses were selling at the far low end of the price distribution between 2010 and 2015 — with around one-in-five homes going for less than $99,000 in the first few years of the decade, and anywhere between 5% and 15% going for less than $69,000. Dallas was truly a place where the American dream of homeownership was alive and well — a place where families that worked hard, lived frugally, and played by the rules could buy a house to call their own within their means.

That’s no longer true. As of 2024, the median DFW home price hovered at a little over $440,000, a nearly three-fold jump from its 2011 level. Now, the income of the median DFW household is barely enough to qualify for a loan to buy a median-priced house in the Metroplex, even for people who can make a 25% down payment, according to the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University. For people who can’t make such a large down payment on a house, the income required to qualify for a mortgage goes up even higher.

And it’s not like the old days, where a family with less than the median income could find a bunch of starter houses listed at far below the median price. The vast majority of DFW homes (<77%) sold for more than $300,000 in 2024, and basically none (~4%) sold for less than $199,000. That’s why, according to a Dallas Morning News study conducted in 2021 (before a massive post-COVID growth spurt in home prices), “about half of households in Dallas-Fort Worth [have been] priced out of ownership of a median-priced single-family home[.]”

In the City of Dallas proper, a recent study found that a household needs to make at least $100,000 a year to afford a typical home within city limits, and that, compared to demand, there is a shortage of around 40,000 homes affordable to city residents making $55,000 a year or less. Meanwhile, over in the suburbs, frustrated would-be homebuyers are resorting to RVs in lieu of continuing to pay (also fast-increasing) rents, causing demand for mobile homes to grow rapidly.

What’s behind this transformation of the DFW housing market? To understand that, we have to look at the dynamics, not of land use regulations, which have remained relatively stable in recent decades, but of two critical segments of the housing supply chain: The homebuilding industry that builds new houses, and the resale market in which people buy and sell existing housing stock. Both have experienced dramatic changes over the past four decades — changes that have progressively constricted housing production and juiced demand for houses as investment assets, driving home prices to rise beyond the reach of an ever-growing share of Dallasites.

We’ll start with homebuilding.

For most of the 20th century, a local general contractor was a keystone part of the American economy. He could buy a few lots, get a loan from a local bank, build a house or a few houses, and sell to families for a profit. Homebuilding was the first industry out of recession, and a way to upskill people into construction. America had big homebuilders and small ones, as well as everything in between. There were lots of bankruptcies, but also a constant stream of new firms — because the barriers to entry were so low.

As the country went, so did DFW. Until the 1980s, homes in DFW were built by a large number of local and regional firms. Only a few homebuilders in the Metroplex were active in more than a handful of markets, and almost all were private, family-owned enterprises funded by local investors and loans from community banks and savings-and-loan institutions (or “S&Ls” for short).

In the face of rapid population and job growth over the 1970s and 1980s, competition among these smaller homebuilders contributed to the affordability of housing in DFW in two important ways. First, this flexible and open market kept a lid on the prices homebuilders could charge for new houses; by extension, it also capped the prices that subcontractors and material suppliers charged for their services and products.

Second, it induced more production. Models of the real estate business cycle used in the homebuilding industry acknowledge a tradeoff between concentration and housing supply. When a large number of firms are competing to build, they “must speculate and start the process of planning development and building new houses earlier than the actual demand materializes.” Since this dynamic tends to “increas[e] total housing production . . . and creat[e] a surplus of unfinished units” compared to demand, it enhanced the availability and affordability of homes for the swelling number of DFW residents.

The heart of this decentralized system was broad availability of bank credit, on roughly equal terms, for both small builders and big ones. It's not a surprise, then, to hear that the financial deregulation movements of the 1980s and 1990s — which laid the groundwork for waves of consolidation that dramatically reduced the number of financial institutions around the country — led to its dismantling. There were a number of legal changes in the long and slow process of deregulating finance, but the basic shift was to move us away from a world where local banks, credit unions, and S&Ls were in charge of lending in their communities, to one where Wall Street institutions hold sway over the allocation of capital and credit on a national or even global basis. To oversimplify, that meant that the reliable builder who paid back his loans no longer had a banker who could handle logistics—giving way to the spreadsheet jockey who eventually began bossing around the builder.

For the homebuilding industry, the most important factor in this shift came in the aftermath of the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s. S&L’s were created in the 1930s to stem the tide of home foreclosures in the wake of the Great Depression and to act as steady engines of incremental housing development in their communities going forward. To keep them focused on that purpose, they were only allowed to do three things: take deposits from local savers, issue mortgages for local families to buy homes, and make loans to local homebuilders to build more homes. Humming along nicely in this low-risk niche, the S&L system stimulated local housing markets with limited incident for the next few decades, becoming a critical source of capital for small builders around the country.

In the early 1980s, however, a series of laws were passed that allowed S&Ls to move out of their housing niche and go into all sorts of speculative endeavors, like junk bonds. As the decade wore on, those speculative endeavors gradually came home to roost — leading to mass S&L insolvencies by the late 1980s. When Congress and the H.W. Bush administration responded to this crisis, however, they didn’t seek to return the S&L system to its roots in safe and steady lending to local housing markets. They went the opposite direction — and orchestrated the large-scale entry of Wall Street firms into the real estate development sector for the first time in American history.

For most of the post-war era, it was difficult for large Wall Street institutions to efficiently underwrite, acquire, and organize local real estate assets at scale, so they generally stayed out of land ownership and development. When Congress sought to deal with the bankruptcies of hundreds of S&Ls in the 1980s, however, it created an agency to do just that — transfer real estate assets to Wall Street at scale. The so-called “Resolution Trust Corporation” took over and carried out a fire sale of the assets of more than 750 failed S&Ls to institutional investors like private equity funds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other financial firms. These assets included not only vast tranches of real estate and construction loans, but also foreclosed properties, building materials, construction equipment, and more.

These assets were sold at deep discounts to their real value, setting the stage for immense profits. Susan Hudson-Wilson, a leading real estate industry analyst at the time, described what the RTC did as “the greatest and most unfair transfer of wealth that has ever taken place in this country—perhaps the whole world.” “Great wealth,” she said, “was literally stolen from people and transferred to a group of cash-rich ‘tide-riders.’”

Meanwhile, actual builders lost their lines of credit en masse. As the RTC showered real estate assets on Wall Street, the banking agencies pushed community banks and remaining S&Ls to curb their real estate exposure, forcing them to “withdraw long-standing lines of credit for builders” and limit the issuance of new ones. With these traditional sources of financing for housing development drying up, homebuilders were forced to turn to capital markets — and the Wall Street firms that gatekept them — to fund the acquisition of land and construction of homes, with severe consequences for the viability of small, local firms.

In this environment, small builders were starved for capital, but large builders with connections to Wall Street flourished, building moats around their businesses based primarily on their privileged access to capital. As these well-connected builders made stock and bond offerings to secure funds from the capital markets, institutional investors and private equity funds came to play a much larger role in the financial structure of the homebuilding industry — including in DFW. Billions of dollars poured into large DFW builders like D.R. Horton, Lennar, and Pulte Group, much of it earmarked for acquisitions of other firms rather than investments in organic growth.

As this trend continued, by the late-1990s M&A became the only way to satisfy the aggressive quarterly growth expectations of Wall Street analysts and shareholders. In 1998, one builder expressed the sentiment of many when he told a reporter: “Wall Street is pushing the big builders to expand at an incredible pace. Anybody who can walk and chew gum is working and overpaid. They are shopping for acquisitions like crazy, and overpaying for builders and land to get into new markets.”

The motivation for these acquisitions was, in large part, the pursuit of market control. For example, Pulte Group’s founder, Bill Pulte (whose grandson now runs the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac for Trump), made his own intentions clear in a 2001 interview: “We want to be General Motors in 1950 with 62% market share and let the next guy down do 30%.” In tandem with that goal, serial acquisitions enabled the biggest homebuilders to pursue another interest of their financier backers: the imposition of greater “discipline” on the building industry.

“An oft-repeated criticism of builders” at the time was “that many consider their principal line of business to be home construction and [so] continue building as long as construction funds are available—whether there is a market for their product or not.” The head of Equitable Investment Management, one of the largest REITs to come out of this era, succinctly expressed the attitude of Wall Street toward this overbuilding habit: “[M]arkets are overbuilt from coast to coast,” he said in 1989; “we’ve got to get more order and discipline.”

And they did get more order and discipline. By 2003, the legendary Harvard Business School professor Michael E. Porter was observing in a presentation to shareholders in publicly traded homebuilders that, while the industry was historically characterized by “[l]ack of inventory discipline” and “[l]ack of capital market discipline” that frequently led to “overbuilding and competition on price,” the “[g]rowing share” of housing construction “held by large public homebuilders” was allowing “[l]arge builders [to] provide greater inventory discipline in the market” than had prevailed in the past. Here’s a slide from his remarkable presentation making the point about financing advantages, which today is echoed in the investor docs for the big publicly traded homebuilders.

Although this late 1990s/early 2000s wave of consolidation hit the bubble markets of that era (Arizona, California, Florida, and Nevada) the hardest, it affected Texas, too. A 2009 study found that the top four Texas homebuilders during this period — D.R. Horton, Pulte, Lennar, and Centex — grew through no less than 65 acquisitions between 1993 and 2005. By the end of this period, these four national conglomerates controlled more than 20% of all home construction in Texas, and likely enjoyed even higher market share in major cities. As concentration grew, the trendline of new home starts began slowing down in DFW — going from around 6.5 homes per thousand residents in the 1980s to less than 5.5 homes by the mid-2000s (see Figure 5).

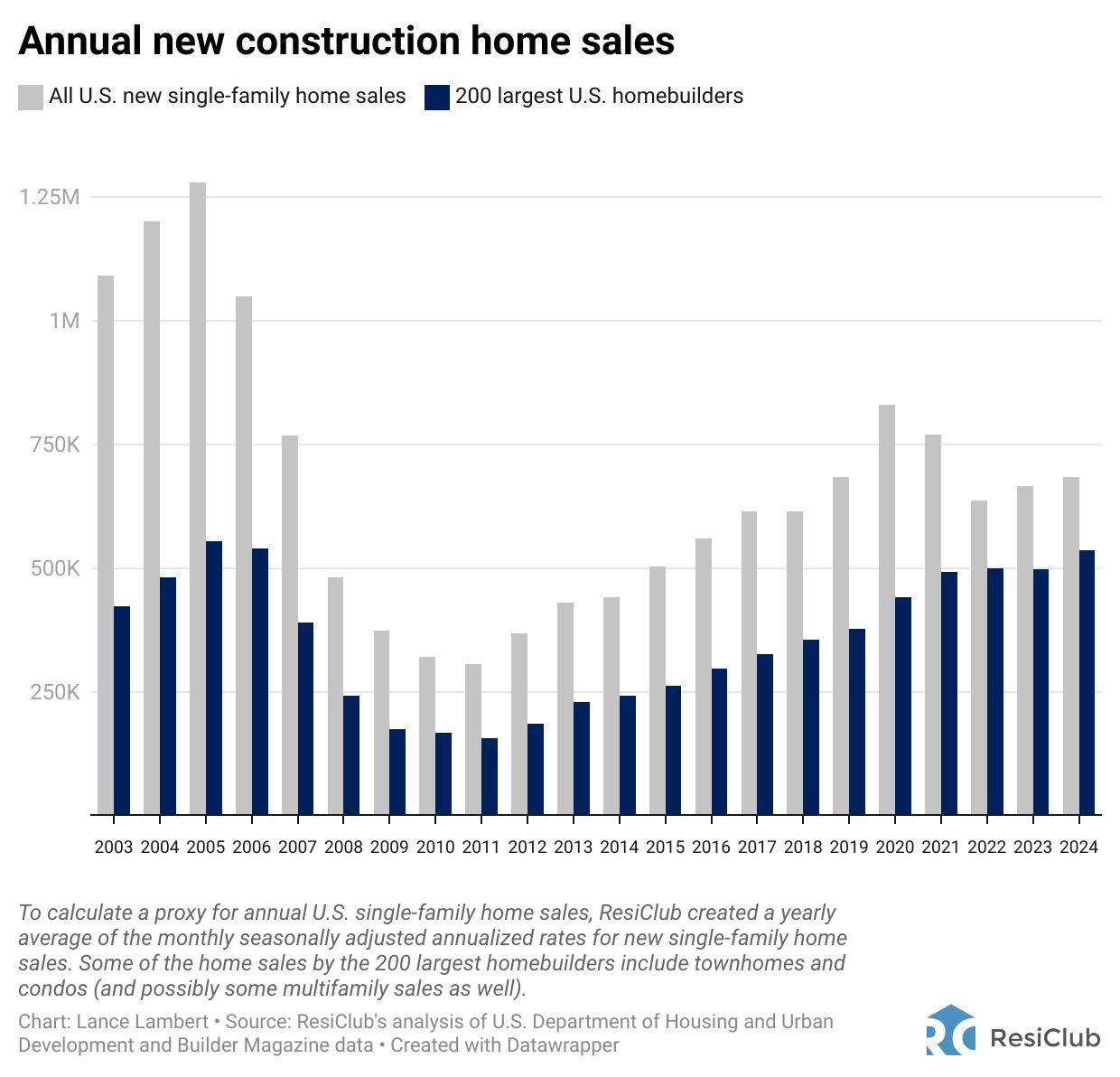

After the Great Financial Crisis, consolidation really hit overdrive among builders in Dallas. A wave of bankruptcies and liquidations washed across the homebuilding industry between 2008 and 2010, both in North Texas and around the country, leaving dozens of small and mid-size DFW builders shut down or sold out. Simultaneously, a federal legislative stimulus measure enacted in 2009 delivered $2.4 billion in tax refunds to homebuilders, with the bulk going to the largest national firms — giving them tremendous liquidity while the rest of the industry wallowed in crisis. An M&A frenzy promptly took off across the North Texas homebuilding community and raged for the next decade, leading to the absorption of dozens of area builders into large publicly-traded conglomerates.

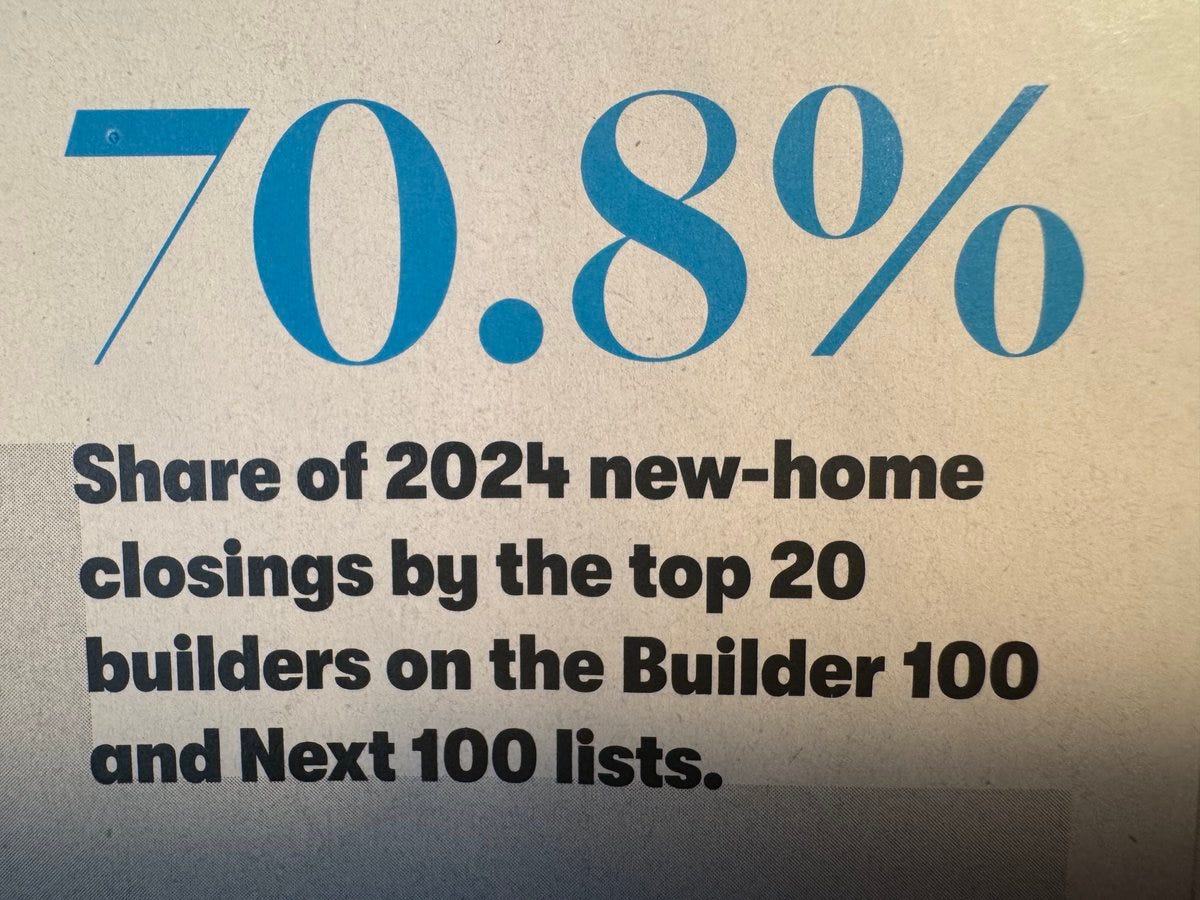

The share of DFW new home sales controlled by the top 10 firms went from around 35% in 2007 to nearly 51% in 2010. On its own, D.R. Horton doubled its market share from around 8% to more than 16%. By the beginning of 2024, the top 10 firms’ share of new home sales in DFW had climbed even further to 60%, and the top 2 firms (D.R. Horton and Lennar) had come to control more than 30% of closings by themselves. Today, nearly all new home closings in DFW (85%) are carried out by less than 30 builders — and an ongoing “explosion” of M&A activity that started last year and has “show[n] no signs of slowing down” is only making things worse.

In the shadow of all this consolidation, the financial power and sheer size of the largest DFW homebuilders have allowed them to dig deep, wide moats against competition from upstart builders. At this point, 8 out of the 10 largest homebuilders in DFW are either publicly traded companies or subsidiaries of publicly traded conglomerates, and these public builders have become far larger than their non-public rivals. Described as “unstoppable, market-share-devouring juggernauts” by Builder’s Daily magazine, these dominant incumbents appear to deploy their power to undermine free and fair competition in at least two significant ways.

First, using their ability to access more capital at lower cost from equity markets, the largest homebuilders have launched their own mortgage companies. They use these mortgage companies to offer loans at below-market interest rates (as low as 3-4% compared to market rates of 6-7% or more) to induce homebuyers to purchase houses at higher sticker prices. According to John Burns Research & Consulting, a leading housing industry consultancy, the largst homebuilders offer these below-market loans primarily by purchasing so-called “forward commitments” from private equity sources, which “provide tranches of money at below market rates” that the builders then use “to originate [below market-rate] mortgages for their buyers.”

By facilitating high-priced home sales with these cut-rate mortgages, large homebuilders impose a double handicap on small builders while inflating property valuations in the region as a whole. That’s because, to match the monthly payment and interest savings that a buyer could realize from a mortgage rate reduction, a home seller generally has to offer a steep home-price discount. Every point shaved off the interest rate on a standard 7% mortgage brings down the homebuyer’s monthly loan payment by the equivalent of a ~10% decrease in the total purchase price. Since large homebuilders are offering mortgages at 2-3% lower rates than traditional lenders, a small homebuilder (or a regular person selling their home, for that matter) would have to set the price of their house at roughly 20-30% below the price of a comparable house from a large homebuilder just to achieve parity — not an advantage — in monthly cost to the homebuyer.

Obviously, this dynamic puts small builders at a severe handicap in competing for sales to the typical buyer, who has a limited monthly budget. It also undermines competition in a less visible, more insidious way. By tying home sales and mortgages, Dominant homebuilders can sell their houses at higher prices with higher gross margins, while issuing bigger mortgages with bigger origination fees and bigger resale values on the securitization market. As their below-market mortgages get buyers to accept higher sticker prices, these inflated prices feed high-priced comps into local property databases — pushing land and home valuations up market-wide. The largest homebuilders benefit from this dynamic because they sit on large amounts of real estate whose valuations they want to maintain or raise, but it makes it that much more expensive for small builders to buy land to build on in the first place.

Beyond mortgages, large public homebuilders wield their scale and financial privilege to reduce their own costs and increase their competitors’ in more direct ways. By exercising their massive purchasing power, big homebuilders extract preferential discounts and exclusive deals from building material suppliers and subcontractors. Indeed, “[t]he scale and sway of market leaders” — particularly D.R. Horton and Lennar — means they “often monopolize access to trades and vendor resources” in local markets, constraining the ability of smaller builders to build at all, according to Builders Daily. As these dynamics force small builders to wait in line for supplies and workers — or pay extra for them — they undermine the ability of small builders to compete against the dominant incumbents on either price or output, leaving those incumbents with even more market power against homebuyers.

Putting all of this together, it’s pretty easy to see why industry sources report that leading DFW homebuilders like D.R. Horton and Lennar have been earning unheard-of 30-50% profit margins on new home sales in recent years — while failing to build anywhere near enough houses to satisfy demand.

The direct result of these changes in the financial and corporate structure of the DFW homebuilding industry has been — wait for it — housing shortages. Homebuilders have “more land for housing and less housing regulation [in DFW] than [almost] anywhere else in the country.” Over the last 15 years, they’ve also had a hot housing market, with growing demand for homes, rising home prices, and favorable financing terms, both for developers and for homebuyers. Nonetheless, homebuilders have built fewer houses than necessary to satisfy Metroplex demand in every year since 2012, according to recent reports by Up For Growth, resulting in a progressively growing deficit of housing production that reached above 121,000 units by 2022 — a “spik[e] in underproduction far in excess of California.”

As the 2010s wore on, that escalating shortage of houses helped drive the median home price in DFW up from around $150,000 in 2011 to around $267,000 in 2020.

As Johns Hopkins School of Business scholars explained in a 2019 paper: “[I]n a more concentrated market, [homebuilding] firms can time their housing production to maximize their profits without fear of pre-emption. This lowers production volumes but increases price volatility as firms with market power can opt to build when demand growth is strongest and charge prices higher above their marginal cost of production.” Interestingly, over the past two decades the DFW homebuilding industry has developed just the infrastructure to help leading firms monitor each others’ production choices and restrict when, where, and how much housing they build without fear of pre-emption by competitors.

Over the past two decades, most — if not all — significant builders in DFW have converged on the same source of market intelligence to drive their decision-making: a consulting firm named Residential Strategies, Inc. (“RSI” for short). RSI offers builders an online database where they can monitor each other’s new home starts, inventories, sales, and even prices in any part of the Metroplex, all the way down to specific submarkets and neighborhoods. On top of that, every quarter RSI staff organize in-depth presentations detailing “current market trends, information on market drivers, and a detailed synopsis of each [DFW] submarket” — complete with forecasts of demand — that are attended by a wide cross-section of the DFW homebuilding industry. While RSI is reportedly careful not to share sensitive information or facilitate explicit collusion among builders, it does not have to do so to play a role in limiting competition. By enabling rival builders to monitor each others’ production activity and “read from the same book” in making their production decisions, it’s not hard to see how RSI’s tools could be facilitating reductions in total housing output.

And reduced housing output has, in fact, been reflected in the data on DFW homebuilding. As Figure 5 above shows, the trend line for new home starts in DFW declined dramatically between the 2000s and the 2020s — reaching nearly 4 homes per thousand DFW residents this past year. Even at the peak of homebuilding activity in the present real estate cycle, the number of new homes built in a year barely exceeded 6.5 per thousand DFW residents — compared to 8.5+ homes at the peak of the mid-2000s cycle and 10+ homes at the peak of the 1980s cycle.

So far, I’ve discussed those who add new supply. But there are of course a lot of people who sell their homes and move every year, and those homes go on the market, too. During the pandemic, a spike in interest rates caused many homeowners to get locked into their existing low interest rate mortgage. So there was an artificial limit on supply, leaving new homebuilders in control of the housing market.

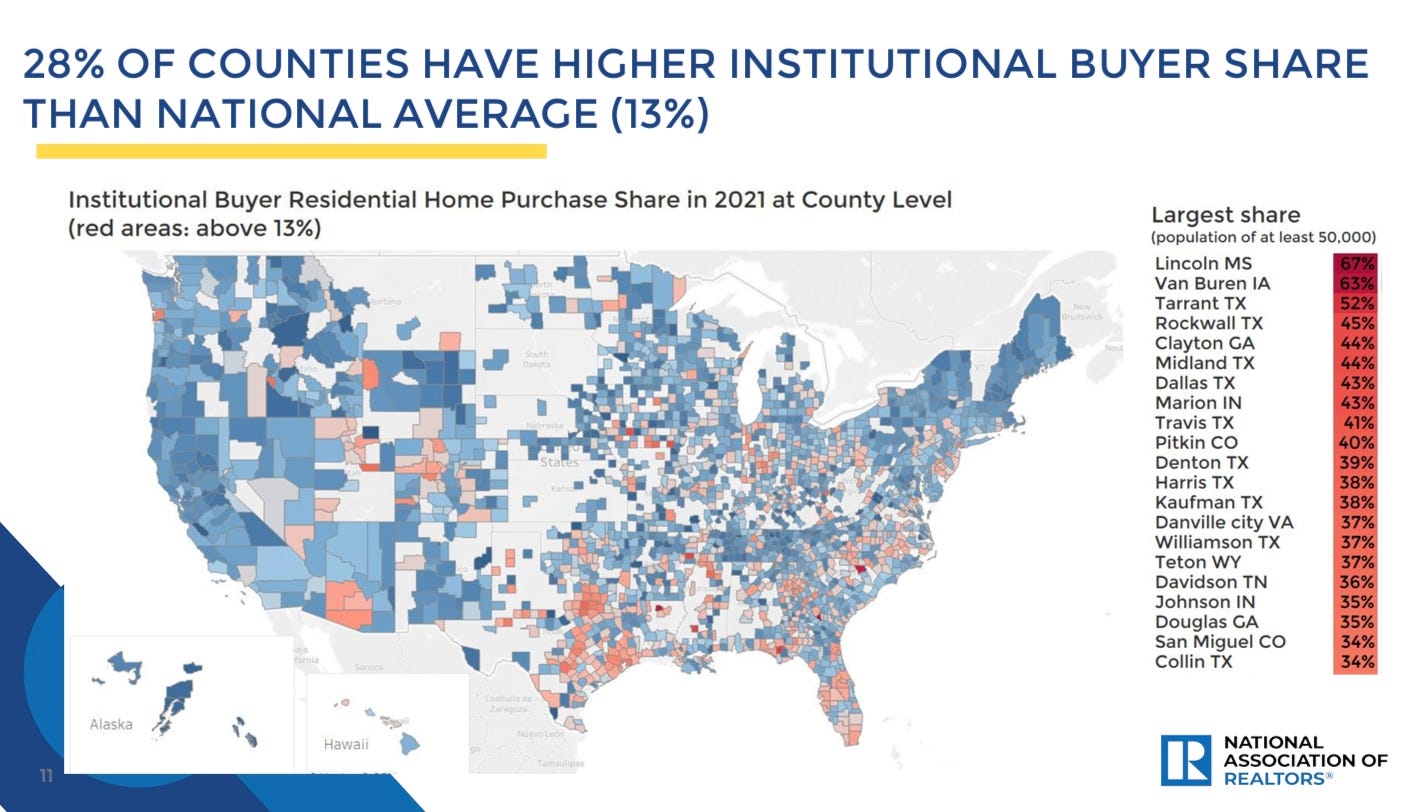

But something else happened as well — institutional investors entered the DFW single family home market at scale for the first time. As if lighting a fire in the middle of a drought, a private-equity-fueled boom in single-family home purchases took off across DFW in 2021 and hasn’t abated yet.

This dynamic has also been driven by policy. Just as the fire sale of real estate assets after the S&L Crisis entrenched Wall Street in commercial real estate, the sale of large swaths of foreclosed homes after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 created the conditions for private equity investors to be able to treat single family rental homes as a scalable financial asset.

Before then, it was impractical for, say, Blackstone to buy tens of thousands of homes one by one. When the Department of Housing and Urban Development started putting bundles of them on sale in the early 2010s, however, it became much simpler. Investors started buying up homes in droves. An entirely new set of buyers began taking the iconic American home and turning it into the property of distant financial masters. “America,” Morgan Stanely proclaimed in a 2011 report, “is moving away from a home ownership society and towards a rentership society.”

DFW became a prime target for this movement in the early 2020s — likely because Metroplex home prices had remained low compared to Metroplex incomes, giving investors room to raise them without destroying homebuyer demand. According to an analysis by the National Association of Realtors, institutional buyers (trusts, corporations, limited liability companies, etc.) accounted for anywhere between 34% and 52% of single-family home purchases in the most important counties of the DFW metro area in 2021, and were paying a median price more than 1.7 times the median price paid by individual buyers. That — together with inflationary conditions in the broader economy — created an opening for home sellers to raise prices dramatically. The median home price in DFW rocketed from a little over $267,000 in 2020 to more than $400,000 just two years later — and it hasn’t come down since.

Buoyed by slowdowns in construction and below-market mortgages by dominant homebuilders, DFW home prices have remained stubbornly high even as actual sales have slowed down over the last couple years — and Dallas has continued to be market where sellers have more pricing power than homebuyers, according to an analysis by ResiClub. Dallas, like a growing swath of America, is no longer for the middle class.

The principle of American political economy before the 1980s was fairly simple: We wanted broadly dispersed property ownership, because if everyone had a stake in this society then everyone would want to preserve it.

What we meant by “property ownership” was not only dominion over land, or goods, or business, but responsibility for them as well. We understood that owning something meant caring for it and stewarding it for the community, so we expected ownership to be an extension of people’s vocations. Hospitals were to be run by doctors, industrial firms by engineers. Building was to be organized by builders, and the homes they built were to be owned by the families who lived in them. And the financing for it all was to be provided by local bankers and credit unions and saving associations — themselves outgrowths of local business and local thrift and local wealth. There were problems and exceptions, of course, but this was the basic philosophy underlying our political order and our policy apparatus.

Today, that philosophy is all but forgotten in high places. Our policies are structured so that the home is less a place to live than a cash-flowing asset for Wall Street to print and sell mortgage-backed securities off of — and homebuilding is not a vocation to produce homes for local families so much as a means of generating a high return on equity for distant capital allocators. We shouldn’t be surprised that these policies have led us to a world with less and more expensive housing. From the perspective of the financiers we’ve put in charge of homebuilding, that’s the whole point of the enterprise.

Once we understand that, it becomes quite obvious what we have to do to stop our slide toward a “rentership society” and bring back the American Dream: We must decide that homes should be owned by homeowners, and that homebuilders should be builders — not land speculators and asset managers for Wall Street. Practically, that means three major things: First, it means we must ban Wall Street and institutional ownership of single-family homes. Second, it means we must make it easier for builders to get bank loans by restructuring our financial sector. Third, it means we must attack the practices and institutions that dominant homebuilders have used to limit competition between them and handicap the ability of outsiders to challenge their dominance.

But what about the zoning and building code reforms suggested by Klein and Thompson? Those would be good things to pursue as well. They would certainly remove burdens that fall disproportionately on small homebuilders, and help to foster competition in that way. As Michael Porter observed in this slide from 2003, excessive land use regulation accentuates the power of large homebuilders, and helps them box out smaller ones. We should fix that.

But we also have to be realistic about how much code reforms can accomplish in the face of the concentration of economic power in the housing-finance-industrial complex. If small homebuilders can’t get financing for their projects because big banks won’t lend to them, or can’t get skilled trades because the largest builders are hogging them, then zoning reform won’t help them all that much. And if the threat of competition isn’t there to spur the largest builders to build more houses, it won’t matter that the zoning codes technically allow them to do so.

In the end, there is no running away from the truth: We need a holistic strategy to dislodge the powerful corporations throttling housing production in this country. Reforming local codes can be a part of that strategy, but it can’t be a silver bullet. To be sure, I didn’t study San Francisco and Los Angeles — which seem to be the places that most shaped Klein and Thompson’s thinking — and maybe those cities have exceptionally restrictive land use regulations. Even there, however, I think more analysis incorporating finance and market power could help: Just by glancing at this list, I can already see that, as consolidated as Texas homebuilding has become, the California homebuilding industry might be even worse.

Ultimately, what the foregoing analysis of the DFW market demonstrates is that the housing crisis is not unique to blue states or red states; it’s a national phenomenon driven by our concentrated and bloated financial sector — and the monopolists it has backed to constrain housing production, accumulate pricing power, and extract profits from the rest of us. To put this in sharper terms: The exorbitant rents and home prices of the post-Covid era have fed the emergence of over a dozen homebuilder billionaires just since 2022. The problem, as much as Klein and Thompson may wish otherwise, is oligarchy.

.png)