We could be on the verge of ending the longest government shutdown in U.S. history—though nothing is guaranteed.

While Congress debates whether to extend subsidies for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) coverage, Americans with all types of insurance are bracing for higher premiums, narrower networks, and more impossible choices.

So, to me, the debate in Washington is far too small. The real story isn’t just whether subsidies stay or go—it’s how completely insane our health care system has become, and whether there will be a serious effort to address underlying costs in the system.

I know juuussstttt enough to get in trouble, so I partnered with the incredible Hayden Rooke-Ley, who is a leading national policy expert in this area, to break down the five ways the entire system has gone off the rails.

Let’s dig in.

Over the past two decades, the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance—how the vast majority of privately insured Americans obtain their health care—has skyrocketed. Premiums, deductibles, and out-of-pocket costs have all soared—far faster than wages.

This widening gap means workers earn less, even when their salaries rise on paper. Every dollar going to premiums is a dollar not going to rent, groceries, or childcare.

And the human toll is clear. One in three Americans has medical debt, and more than half worry they’ll fall into debt any time they use the health care system. That fear changes behavior: people delay appointments, skip medications, or avoid care altogether.

Medical debt is now the most common form of debt in collections ahead of credit cards, utilities, or personal loans. Nearly 60% of those in medical debt have insurance.

The United States spends far more on health care than any other wealthy country yet achieves worse outcomes, less access, and a more demoralized workforce.

Outcomes: Despite record spending, Americans live shorter, sicker lives than peers in Europe, Canada, or Japan. Infant mortality, maternal mortality, and chronic disease rates all rank near the worst among high-income nations. A key reason is that we pour money into specialty medical services while underinvesting in prevention, such as primary care and social supports like housing and nutrition.

Access: Critics often argue that “at least we don’t have long wait times like other countries.” However, increasingly the opposite is true (and this is never a fair comparison, as we spend twice as much as they do). More than 100 million Americans live in a primary-care desert, while almost 60 million live in a pharmacy desert. Services to treat mental health are notoriously lacking, and Medicare does not even cover long-term care.

Clinician workforce: Health care workers are burning out or leaving the profession altogether. Home health care aides are paid extremely low wages for heroic work. As corporations attempt to convert salaried positions into gig work, some nurses are compelled to bid against one another for shifts. Many physicians report moral injury working in systems that prioritize billing over care, eroding autonomy and morale.

There’s a common myth, especially amongst policymakers, that we spend too much on health care because we consume too much of it. A similar narrative has taken hold about doctors: because they get paid for each service, they provide too much care. Certainly, there is low-value care in the U.S. health care system. And as profit-seeking corporate actors own more and more of the system, they’re finding ways to bill for more—and more expensive—services.

But Americans don’t visit the doctor more, we don’t go to the hospital more, and we don’t stay in the hospital for longer. We even get significantly fewer of many of the most popular procedures—like coronary angioplasties, knee replacements, hip replacements, and gall bladder and prostate removals. The real difference is price. Take a look at this graph, as one example for hip replacements:

A colonoscopy or MRI can cost 10 times more at one hospital than another across town, depending on which insurer you have. These differences have little to do with quality or cost of care. They’re the result of opaque negotiations between insurers, hospitals, and pharmacy benefit managers, and other middlemen in the system. We’ve created a system where no one knows what anything costs: not the doctor, not the patient, sometimes not even the insurer. The surprise bill arrives weeks later.

On top of high prices, our system is drowning in private-sector bloat and bureaucracy. More so than any other country. Every insurer has its own prices (and endless price negotiations with providers), billing processes, prior authorization rules, and reporting requirements. The result is staggering inefficiency: roughly one in four dollars spent on health insurance goes to something other than care, like marketing, billing, profits, or middlemen.

Doctors spend nearly half their time on paperwork. Patients spend hours on hold, fighting over denied claims. And all of it is baked into costs.

Perhaps the most underappreciated transformation of the past 40 years is the corporate consolidation and financialization of medicine. Care delivery—once local and community-based—is now dominated by corporations.

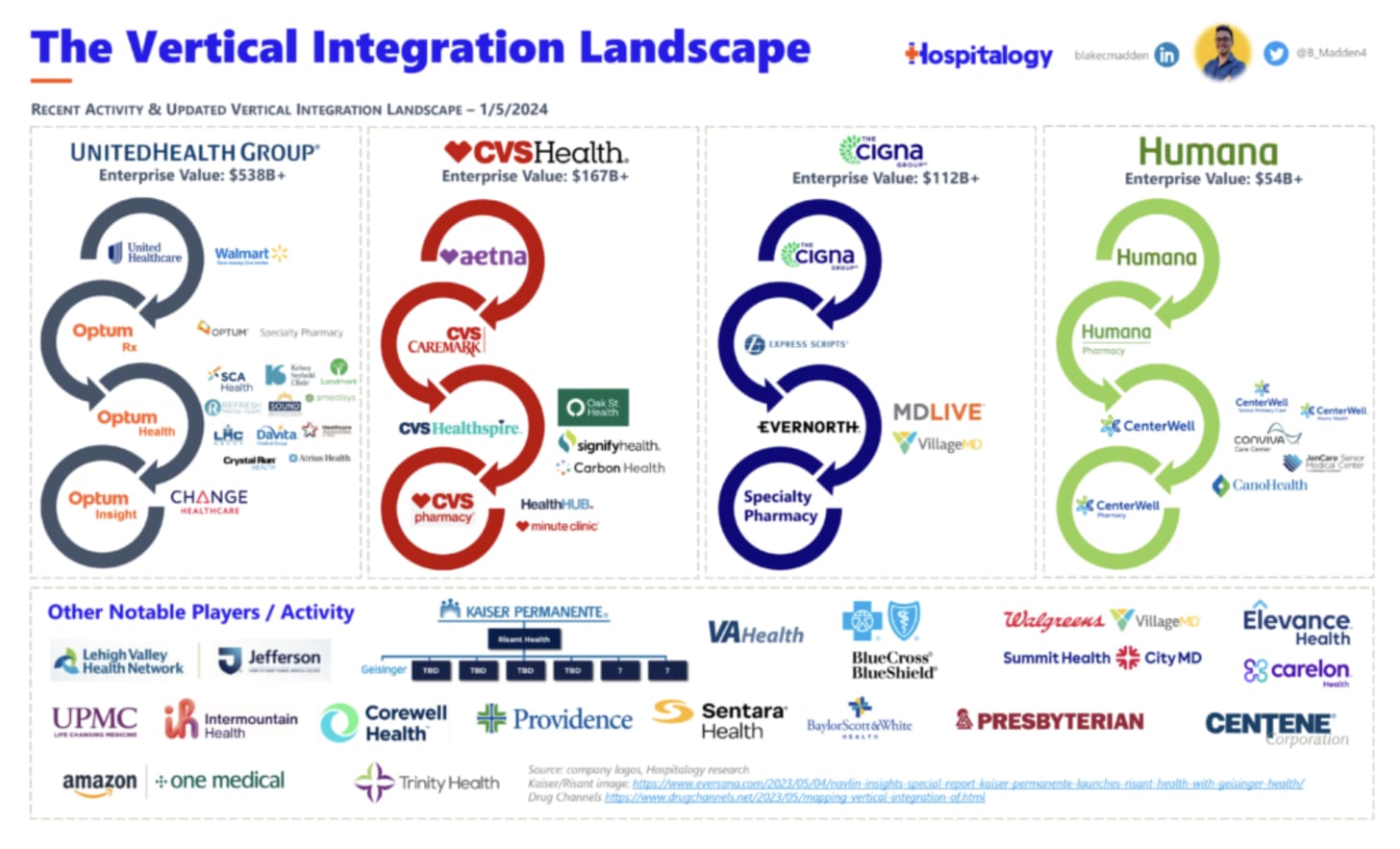

Vertical consolidation is now a defining feature of American health care. UnitedHealth Group isn’t just the largest insurer; it’s also the largest employer of physicians and the largest operator of home health and hospice agencies. CVS Health, the largest pharmacy chain, also owns the biggest pharmacy benefit managers—and now giant insurer, Aetna. McKesson, a pharmaceutical distributor, now operates the nation’s largest chain of oncology practices and is rapidly expanding into other specialties. These combinations raise all the conflicts of interest you’d expect—higher prices, business steered away from independent providers and pharmacies, gaming regulations, and more.

Hospitals have been on a similar trajectory. No longer charitable facilities, they’ve been buying up physician practices, starting insurance plans, and operating financial investment firms. Public hospitals have declined sharply, while giant for-profit systems, such as HCA Healthcare and CommonSpirit, have expanded nationwide. In half of U.S. metro areas, just one or two systems dominate the market.

Then there’s private equity (PE). From 2000 to 2020, PE’s footprint in health care exploded 25-fold—from $5 billion to more than $100 billion a year in deals, totaling over $1 trillion.

Private-equity firms now own everything from nursing homes and hospices, to emergency departments and physician practices. Their model is simple: buy up fragmented practices, cut labor costs, raise prices, and resell for profit. Evidence shows quality declines, and in some cases, mortality rises, after PE takeovers.

None of this happened by coincidence. Our current governing approach began in the 1980s, when a bipartisan consensus emerged around how to address accelerating costs in the system. The idea was to embrace more free market principles in health care, resulting in three significant shifts in how we approached policy:

Private insurers compete for patients (called managed competition), which was hypothesized to lower costs and improve quality. In reality, the government pays hundreds of billions to the nation’s largest insurance companies, which now operate most of Medicaid and Medicare, and all of the ACA exchanges. The same happened with prescription drugs: instead of Medicare negotiating prices directly with pharmaceuticals, it’s now the job of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), costing Americans more.

Overreliance on economic incentives—the notion that physicians and patients won’t do the right thing unless they have more “skin in the game.” Democrats embraced this ideology by pushing physicians into “value-based care,” a rebranding of HMO-style managed care, and a close cousin of privatized Medicare. On the patient side, Republicans insisted that they actually needed higher deductibles, so they would ration their care more wisely. But, again, Americans don’t “use” too much health care. Plus, a patient can’t “shop” for emergency surgery or chemotherapy.

Commercialization: The U.S. began converting public hospitals to for-profit chains, and abandoned care delivery models with commitments to voluntarism (i.e., actual non-profits) and professional ethics (i.e., clinician-owned medical clinics).

The current debate recycles the same logic: more private control, higher out-of-pocket costs, and less regulation of prices or profits. The latest idea is that deductibles need to be higher and patients don’t pay enough.

This approach has failed for 40 years. It will continue to fail because it doesn’t address the true crisis of U.S. health care: high costs from high prices (especially for new technology); consolidation and extraction at every level; and lackluster and misallocated capacity.

The U.S. health care system is uniquely dysfunctional. A different approach is entirely possible—if we have the will to boldly govern the health care system in the interests of patients, clinicians, and taxpayers. That means directly tackling prices, eliminating middlemen, and breaking up behemoths. It also means returning ownership of care delivery to clinicians and communities and pursuing a strategy that builds the workforce and capacity to meet Americans’ needs.

Health touches everyone, and we need a system that works for us, not one that makes us work for it.

Love, YLE and HR-L

Hayden Rooke-Ley, JD, is a Senior Fellow at the Brown University School of Public Health. His scholarship focuses on corporate consolidation in health care, Medicare and Medicaid financing, and labor and workforce issues in the health sector. He has published in leading journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine and Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), and he advises state and federal policymakers, enforcement agencies, and other health care stakeholders. He is a licensed attorney in Oregon and earned his JD from Stanford Law. His work can be found on X and LinkedIn.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE is a public health newsletter that reaches over 400,000 people in more than 132 countries, with one goal: to translate the ever-evolving public health science so that people are well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members.

.png)