Well, that was a wild ride. As of the time of this writing, College English majors can’t read has 120,000 views and 535 comments. Comments and restacks are still rolling in but not at the furious pace they were in the few days after publication. It went viral on twitter, with my tweet announcing the article getting 768 retweets and 1.5M views, with thousands of comments spread across various quote tweets. It was shared to Reddit in several different threads, many of which themselves spawned hundreds of comments. It went viral on Hacker News. It was shared on Vox Day. It was published on Revolver News. Hundreds of people linked it in their Instagram and Facebook posts. A bunch of people shared it on Slack or Microsoft Teams. And most endearing of all, thousands of people forwarded the newsletter around by email like an AOL chain letter from your grandma (Fwd:Fwd:Re:Fwd: You won’t BELIEVE what they are teaching in college now!!!!)

It even got picked up by Vaush on his stream. If you don’t know who that is, please don’t look it up, just understand you have my eternal envy.

The people have spoken, and they speak in a single clear voice: they want to hear about how dumb college kids are. They want to bathe in delicious schadenfreude. They want all the embarrassing and gory details about how Suzie in Kansas couldn’t figure out what a megalosaurus is, how heavily she breathed during the 16 seconds she tapped Google searches into her phone before giving up. And their bloodlust will be slaked one way or another.

Most of you reading this have probably never had something go viral. Not to brag but I’m kind of a big deal on twitter, so I’ve had a bunch of different tweets crest the multi-million view mark and I’m somewhat familiar with the process and what it feels like. This felt different. It felt like I started a conversation way bigger than me and outside my control.

My phone was buzzing non-stop with Substack notifications all day and night. Seeing notifications makes you feel good, so you check your phone when it buzzes and get rewarded with a little squirt of dopamine. This reinforces itself and quickly becomes Pavlovian in its addictive quality. And it doesn’t go away when the buzzes happen every couple minutes, all day long, as you’re trying in vain to write important B2B SAAS code.

Eventually I had to block substack on my desktop browser and put my phone in a drawer to stop checking it all the time. This was better than keeping it in my pocket or on my desk, but wasn’t a perfect solution.

But what are you going to do, not get high all day on the attention of strangers? How many times do you think this happens in a typical lifetime, you think you can just press pause on that and go about your business? Get real.

I did not get a lot done those couple days. (I also picked a silly but entertaining fight with another substacker in this same interval, so I had two things going at once.) It was fun, but not productive.

People had a lot to say in the comments, here and in other places it was shared. I read a great deal of them, but there were too many to digest them all or to quote them individually. I did pick up on a few general themes that I heard multiple times, some of which I’ll go over now.

There were also some very funny memes.

I got this comment a bunch of different times, and I think that one particular guy made the same comment at least four different times that I saw, in different places. Basically, this nitpicking goes: these kids can read just fine, they just have trouble understanding and interpreting hard texts, and this means the title is sensational and not literally true. This is a fair point, and I deeply treasure our nation’s strategic reserve of turbospergs ready to call out technical inaccuracies wherever they rear their ugly heads. I should note for the turbospergs reading this that “rearing their ugly heads” is figurative language, article titles do not have bodies and do not move, you have me dead to rights on that one.

But most readers were quick to chide the spergs that this is an article about different levels of functional literacy, and that “read” can have different connotations depending on the context. Obviously we’re talking about more than just sounding out the words on the page in this case. And also, College English majors can’t read is just a much better title than the long but more technically accurate one you would have me write instead.

A lot of people made this comment in one form or another, for a variety of reasons. If you want to read a detailed takedown, I suggest this long post by Holly MathNerd. She has a lot of different objections about the methodology and how the results generalize to the population of college kids. It’s worth reading and taking seriously if you’re the scientific minded type, she knows what she’s talking about.

One very large objection that should give you pause: there are multiple layers of potential selection bias taking place. We’re looking at just a couple schools in Kansas at a single point in time, not a nationally representative sample of students. These aren’t exactly top-tier schools, of course they don’t have the best kids! And worse, they recruited study participants the way they always recruit undergrads for this kind of study, by asking for volunteers in class or even by hand-selecting students and encouraging them to join up. This means the researchers weren’t getting a random sample of their students, they were getting the kids who were dumb enough to waste their time on a silly research task. Or even worse: they picked problematic kids on purpose to prove a point.

This is a fair criticism, and I don’t want to minimize it, but I don’t think it ultimately matters much. The reason is that we know how these kids tested on the ACT Reading subtest and how that compares to the national standard.

The 85 subjects in our test group came to college with an average ACT Reading score of 22.4

The national average for college students on the ACT Reading subtest is 21.2, so these kids are a bit above average nationally. (20 to 23 is considered a competitive score for admission to most schools, with 24 to 28 being the standard for more selective schools). This is reasonably strong evidence that they are not significantly dumber than typical college students nationwide. Maybe not representative, sure, but certainly not dumber than average.

And despite being competitive for admission according to Educational Testing Service, 22.4 is not a good score!

According to Educational Testing Service, [students with a score of 22.4] read on a “low-intermediate level,” able to answer only about 60 percent of the questions correctly and usually able only to “infer the main ideas or purpose of straightforward paragraphs in uncomplicated literary narratives,” “locate important details in uncomplicated passages” and “make simple inferences about how details are used in passages”

So maybe these results don’t actually generalize to students nationwide, maybe this wasn’t a fair sample. But if you’re skeptical on the question of generalization, another way to view this study is as an ethnography rather than a quantitative result — the researchers discovered and documented a group of college English majors with truly terrible reading comprehension. Whether or not this result generalizes to college kids everywhere, these particular kids exist. And they can’t read. Personally I think the ethnographic details are what make this study so evocative, and I wish more research took this form. My hunch is nobody would be talking about this at all without these details — distilled down to a raw quantitative result (half of kids score below median on test, news at 11), nobody would care.

I heard this objection a lot too. Maybe the kids weren’t properly motivated to perform. Maybe they didn’t much care about doing well at the task, considering it was volunteer work that wouldn’t impact their grade or any other academic outcome.

There could be something here. The idea of not having enough personal pride to answer up to one’s ability on an exercise like this is alien to my personal makeup, but I can imagine students who didn’t care and phoned it in. It’s plausible on its face.

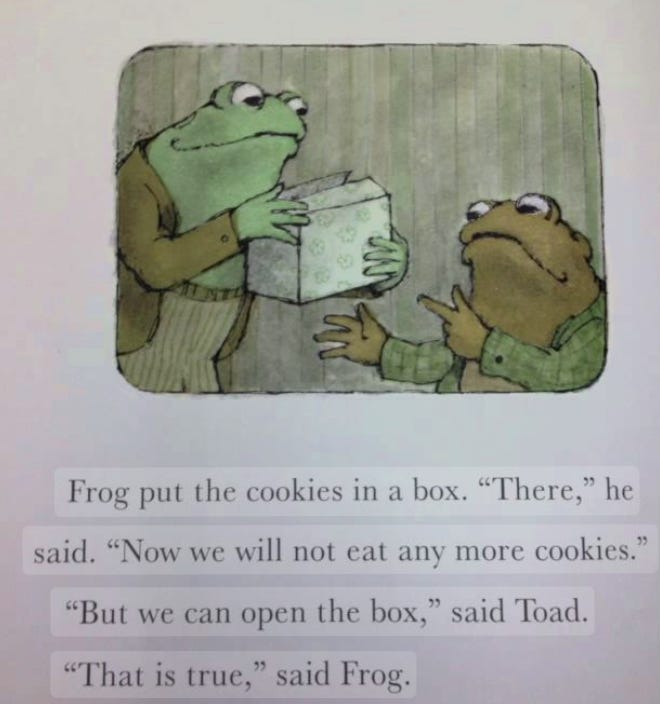

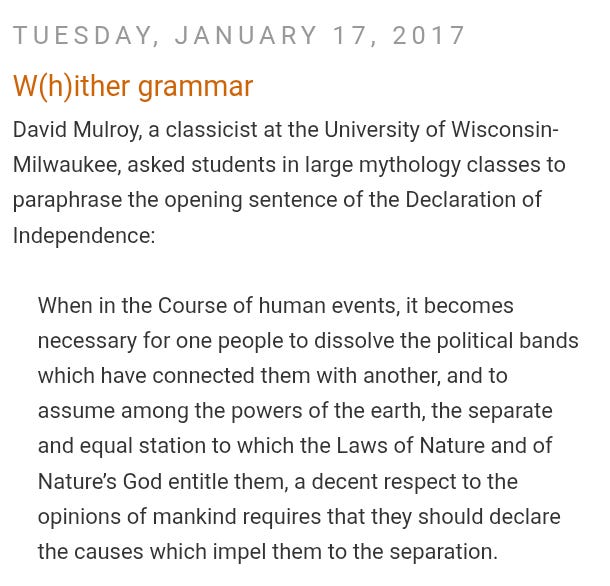

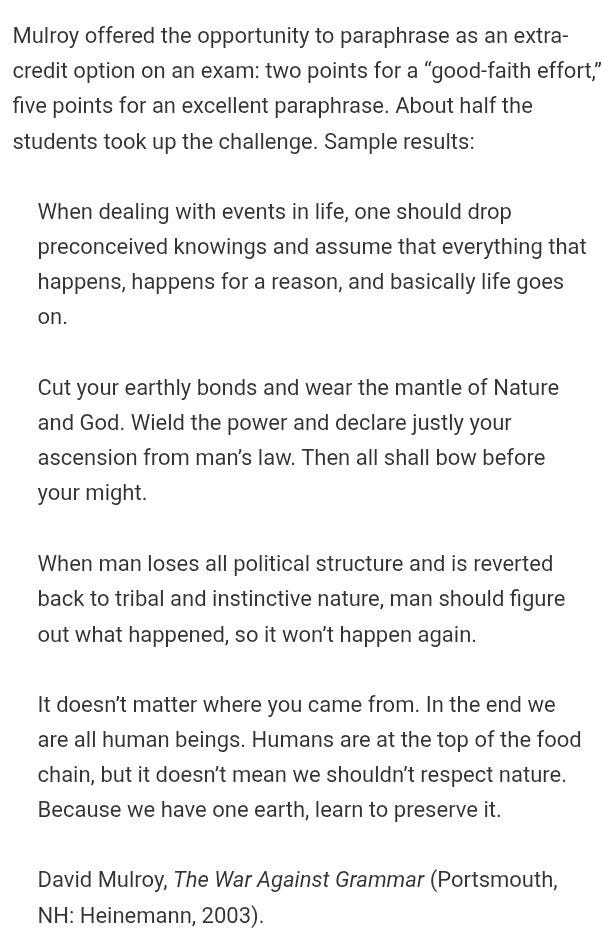

On the other hand, other exercises that do motivate kids with grades see similar results. Here’s what happens when you ask undergrads to paraphrase the Declaration of Independence.

This was a very common refrain among the commentariat, with many offering their opinions about what’s to blame, with phones and TikTok leading the pack. I do think phones are rotting people’s brains in various ways, but I don’t think you can blame them in particular for this result (the data for which was collected in 2015, long before TikTok). I also don’t believe that kids today are substantially dumber than the ones of previous generations.

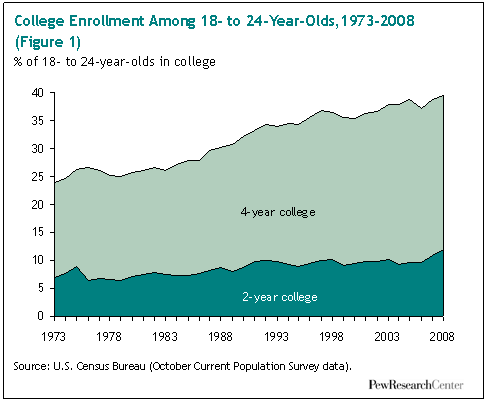

One thing we know for certain is that a much larger proportion of high school graduates enroll in college than in times past (and a much higher proportion of all kids graduate high school than in times past). All else being equal, radically expanding the pool of college students necessarily brings a greater proportion of low-ability students. Such students on the lower end of the ability spectrum were much less likely to attend college 50 or 70 years ago than today.

Many commenters thought it was unrealistic or unfair to expect students to know what Michaelmas, Lincoln’s Inn Hall, or a Lord Chancellor are, or to understand Biblical allusions like the flood. Many others opined that Dickens’ writing in general and these passages in particular are, to use zoomer parlance, not lit or even kinda sus.

The obvious counter-objection is that these students had and were encouraged to use their cell phones to look up unfamiliar elements, and either couldn’t or wouldn’t do so to successfully understand their use in the text. Still, I won’t deny that lacking the background knowledge of what a chimney pot is or what implacable means does make reading more difficult and less enjoyable. But for one thing, that was kind of the point of the study, this is a deliberately hard text. And for another, it’s part of the Western canon, and for good reason.

(Personally, although I’ve never read Bleak House, I found its first seven paragraphs to be incredibly lit, not sus at all, and I plan to pick it up soon.)

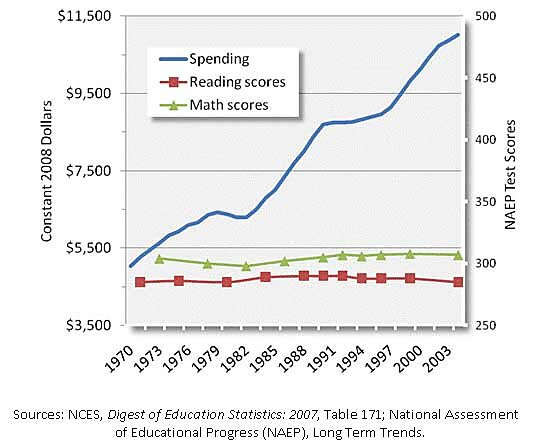

Maybe this is true, but if so we sure don’t know how to fix it. What do you think the goal of the last 70 years of constant educational reforms has been, exactly? Do you think nobody has been trying to do better?

As for the money:

If you want to learn much more about education than I know, from somebody who actually does it professionally, I strongly recommend reading Education Realist. He knows what it’s like to educate lower-ability students and doesn’t pull punches in his stories. He’s also on twitter but his blog is better in my humble opinion.

Finally, hello and welcome to my 1,200 new subscribers. I have no idea who any of you are or what you want from me and I’m a little scared of you.

.png)