Note: This podcast is designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emphasis that’s not on the page

When Computers Have The Final Say

Adam: Hi, this is CoRecursive, and I’m Adam Gordon Bell. Each episode is usually about a piece of software being built. Have you ever had a computer tell you you’re wrong? Insist that you’re wrong, even when you know you’re right? Maybe you try to log in, and it says your password’s wrong, or your payment gets declined for no reason.

I had this with a bank whose reset password button truncated the password before hashing it, or so I later found out when I wasn’t able to log in because the login form didn’t do the same truncation. But these things happen, right? Your payment gets declined for no reason. It’s frustrating, but you call support, they figure it out, or you reset your password again, and you move on.

But what if you couldn’t fix it? What if the computer had the final say, and everyone else—your boss, your bank, the courts, the government—everyone took the computer’s side over yours? That’s exactly what happened to today’s guest, Scott Darlington.

If you build software, or even if you don’t, I think that you know that bugs happen. But what happens if the systems we build end up being trusted more than the people using them?

And if you build software and that happens, where does your responsibility lie? This story is about what it looks like in real life when software hurts somebody and the people in charge and the people building it aren’t listening.

Adam: So, can you tell me your name and how would you describe yourself in 30 seconds?

Scott: Um, my name is Scott Darlington. I’m English, born in Macclesfield, south Manchester, and the county of Cheshire. Oh, how do I describe myself? Um, I’ve always been an optimistic, happy-go-lucky, musical type of person with ambitions and stuff like that, until I came across the dreadful decision to take over a post office.

Adam: Taking over a post office might sound like a strange move, but Scott had thought it through. He had always wanted to be a musician, but now he had a young daughter. And running a business felt like a way to channel his ambitions and give his family some stability.

Here’s how Scott saw it. He could become a sub-postmaster. He’d be the guy who ran the village post office. And to make that happen, he’d borrow against his house. He’d pull some cash from his mom selling her vending machine business, and that would be just enough to buy the shop. If enough people came and went each day, he’d have steady work and a steady income and a business that he actually owned.

It could be something that he could do for decades.

But before he could make that decision, he did some homework. He spent days just watching that post office. He’d park across the street, notebook in hand, and he’d count. He’d count the people coming in. He’d count the people going out. He’d count the cars pulling up and the customers with letters or parcels or pension slips.

He wasn’t casing the place… like I guess he sort of was. He was… was… He was casing it to determine if it was a good business. He was trying to see if this could really be his future. Scott was an optimist, and to him this felt like it could be a fresh start. It could be a place where people didn’t just buy stamps and send parcels, right? They’d pick up greeting cards, they’d buy little gifts. They’d buy little knickknacks. Sitting in his car and counting these customers, it looked like this could be a safe bet.

Because buying the post office wasn’t like picking stocks in the stock market or putting money in a retirement fund. It was more like buying a job for himself, a job that he could actually look forward to, and a job with a future that he could count on and that he’d be excited about.

The Village Dream That Became A Nightmare

Think of it like a franchise. Scott runs the business. He leases the office space. He can work the counter himself, or he can hire staff, and he gets a cut from the post office, and he also gets money from the things he sells in the store.

So after the numbers checked out and the foot traffic looked steady, Scott felt that rush of excitement that you feel when a project is starting and everything is in front of you. He took all his savings and he signed the lease, and just like that, he became a postmaster, specifically a sub-postmaster.

He was in charge of a village post office, that centuries-old trusted institution through which wages were paid, and pensions were drawn, and news of every sort and gossip traveled through a small community.

But of course, Scott couldn’t see what was coming for him. It was waiting behind the counter, inside a beige computer box.

It was the software called Horizon.

Old OS, New Nightmares

Scott: Well, even during the training, which was in this training place, nobody could understand the software too well. It was very clunky. It was Windows NT, which even in 2005 was old. I think it was discontinued in about 1996. I think I might be wrong with that, but they had a special contract with Microsoft just for them to keep the Horizon software updated and things like that, because that software was totally void by then. So they had a special contract just with them, paying them a fortune.

Just for Microsoft to keep updating it, because the cost of replacing it all would’ve been so high. This is one of the reasons why we ended up in this situation. We did, really, because it generally worked. It generally worked, but it was when it went wrong… how they dealt with it. And this was the problem.

Adam: Generally, “worked” is a red flag, especially in financial software. To see why even a tiny glitch mattered, you need to see how money actually moves through these village post offices.

Running a post office wasn’t just about selling stamps, right? The post office was the village’s front desk, kind of acting like a bank for a lot of things. There were pensions being paid out in cash. There were bill payments, there were deposits, and there was just standard parcel stuff. But in a typical week, a hundred to one hundred fifty thousand pounds moved across that counter. That’s like two hundred thousand USD.

Most of that money wasn’t Scott’s; it belonged to the post office or the pensioners, but every transaction paid him a fee, and that’s what made the business viable. Additionally, that foot traffic just lifted up the shop. People coming through would buy greeting cards, snacks, or magazines.

Drowning In Cash And Transactions

Scott: Yeah, it did really, I mean, the amounts of transactions that were taking place every day in the post office, uh, it was phenomenal, really, way beyond what I was expecting. I’d really bitten off something more than I wanted to, but I’d actually got in there and started working, doing this.

So you’re always just gonna get a little… giving someone the wrong change or typing something into the system, a 10p out or something like that, because of the thousands of transactions you’re doing every week. It would be surprising to, for it to actually be absolutely perfect, the cash situation.

So it was gonna be a very, very small part out.

Adam: By month end, Horizon demanded a perfect balance.

Ghost Stamps, Real Debts

Scott: I had a discrepancy from the previous owner. That I had… that I had to pay, that I had to pay. And I tried to chase him up for this money. But, uh, of course it never materialized. So I had to pay about 600 pounds of his debt, as in, I’d only been in there about a week.

So that was not a… not a great start.

But anyway, in 2008, suddenly the system said I was 1,750 pounds out.

Adam: Scott was used to the system being off by a few pennies here and there, but this time the numbers were way off. This was something else entirely.

Scott: And it said that I had stamps to that value in the post office, more than I’d actually got.

Adam: Scott didn’t have the first class stamps. The system claimed he did, but mistakes happen, right? He figured that maybe it would sort itself out. Maybe in a different day it would go the other way.

Scott: The way the system works, you come to the end of like a financial period, which was every month, and you have to… the system has to be set so it’s exact, so it can cut off that period and start a new period. It’s what’s known in their balance that the system rolls over to a new period.

What it can’t do until any discrepancies are resolved, and you can’t just say, ‘Oh, I’ll resolve it, you know,’ because they’ll want the cash.

Adam: Scott contacted the higher ups. He contacted the support line, but basically he couldn’t open the store next day and start doing transactions if he didn’t close the month.

And if he couldn’t do transactions, he wouldn’t have enough to cover his lease or cover payroll. And so he said he was out £1,750 and he tried to tell them that it was a mistake, but what they said was, well, the system says that you owe us £1,750 so we can take it out of your pay, either in one payment or two.

Scott: Uh, so I had to pay it. And that was when the alarm bells were ringing, you know, like, what the hell? What was I saying? Something else is out. I’ve just got to pay that. You know? And you’re dealing with such high-value stuff; it can soon get way out of hand.

The whole risk is on me here because of what this computer’s saying. We knew it wasn’t right, but we’d have no problems before… proper problems. So it was very difficult to blame the system straight away. We just wondered what the hell had gone wrong. You know, how… how could this have actually happened?

Adam: This was a financial setback, and it was terrifying. Scott made only a tiny profit on each transaction, so even small mistakes like this could easily ruin him. And because of that, anxiety started to creep in.

When Millionaires Flee To Your Counter

Scott: Do you remember the financial crash of 2008? That had a big impact on us and everything. There were people queuing up down the streets, paying… some people, paying millions of pounds into post office accounts. I don’t know what it’s like in Toronto, but in the UK, the UK only guarantees 85,000 pounds per account in the event of a bank going bust or anything like that.

So this is no good to the millionaires that lived all around me. They realized very quickly that the post office, which fronted accounts for the Bank of Ireland, guaranteed the total amounts. So, uh, they were just shifting all the money into that, and there was millions of pounds coming over the counter now. And, uh, we’d already had this discrepancy; you know, we were like, oh my God, what’s gonna happen with this?

Adam: One day, Scott found himself 4,000 pounds short, and if he told the post office he knew exactly what they would say.

Scott: I couldn’t really tell the post office about it because I knew they’d just immediately take the money. And when you’re in a small business like that, you’re not in the position to just be paying loads of money out that… seemingly just disappeared. You know what I mean? You’re just not in that financial position. Things can start going wrong. You’ve got wages to pay, you know, bills to pay, and this money is something you haven’t done… if you sort what I mean. They just, they just take it off you.

You had to, you basically had to, adjust the system to say that that money was now in, as if I’d put the cash in, but actually I’m harboring a £4,000 discrepancy in it.

Adam: You had £4,000 more… or 4,000 pounds more in cash than you actually had?

Scott: That’s right. So, uh, which meant the system could roll over thinking that that 4,000 pounds is in, but it’s not. And I’m hoping corrections are gonna come to correct any mistakes we made. Even though we’re new, we haven’t really made any mistakes like this. You know, you’re just hoping upon… upon hope that, uh, something’s gonna come down the line to help out.

Adam: Scott’s stuck, right? If he admits he’s short, he has to pay up and then he won’t have enough left for staff for rent. But if he claims the money’s there when it isn’t, then he’s just betting. He’s just hoping that tomorrow the numbers will magically fix themselves somehow. Maybe someone somewhere will spot the error and things will just set themselves right.

Maybe he just needs a little time, he needs to stall.

The Desperate Lie That Changes Everything

Or maybe there’s another way. Maybe Scott can cover this himself over time. Skip a little bit from his pay each time. Take on some personal debt, pay suppliers late, and eventually that 4,000 pounds will even out. But if the post office needs their money right away, that’s a whole different problem.

So he lies, right? So he says he has the money. He’ll figure it out later, but then there’s another day and suddenly now he’s out 9,000 pounds.

And then the next day it’s even more than that, and it keeps piling up day after day until before he knows it, he’s 44,000 pounds short.

Scott: All of a sudden, you just… total stress, you know, total stress and anxiety, because I know that I’m in trouble as well, and not just financial trouble, but I know that I’m going to be in trouble at some point, whether I lose my contract.

Even if a load of auditors arrive and see the problem, I’ll still lose the contract for dealing with it like that.

Adam: I don’t know, like it feels like you should be able to file a support ticket or something and be like, “Hey, uh, there’s not money here,” or I… I don’t know, like there was no, uh, recourse that you could take somehow.

Scott: No, there was nothing that was… the contracts were reliable, and that was it. They knew that, that they… they’d go to court on that, and they did go to court on that.

Adam: Scott kept the store running, even though he owed the post office more money than he could ever pay back, and still keep the business afloat. He kept it running because the fallout hadn’t hit yet. On paper, he was holding 44,000 pounds for the post office that was theirs, but for now, no one was asking for it, and so he was okay.

When The Auditor Finally Arrives

Scott: What happens in a… in this sort of cash situation like this, you end up with too much cash in, and you need to take… get some outs, and you get cash vans to come and collect it, take it to cash centers, and that ‘cause you end up stuffed with cash. And it’s not very good for security.

It’s not very practical to have so much cash. So, I always used to keep the sort of amount in this post office about 80,000 in cash ‘cause you have pensions to pay. Surprising how much you… is paid out from this. Suddenly, I’m 44,000 out now, and the system came up with an amount that it wanted me to remit out to bring the amount held in the office down to a sensible level, and I couldn’t do it. It would mean I’d have about 10,000 left, and the post office wouldn’t be able to operate. So, I ignored it. I ignored this request, and two days later, one of their auditors arrived to find out why.

So, that was when the ax fell down. But I was pleased that the auditing was there ‘cause I thought, I don’t have to hide anything anymore. Surely now I’ll probably lose my contract, but surely now all the errors that have happened in my branch will come to light. But they never did the slightest bit of investigation.

They just immediately started prosecution proceedings. This is how they operated.

Adam: Did you try to explain, like, to the auditor, like, how did that go down?

Scott: Yeah, they just… they just didn’t believe you. They just didn’t believe you. They just presumed you’ve nicked it in there… as they presumed you’ve stolen it. So, um, they didn’t… they didn’t listen to any explanations or… as far as they were concerned. You spent it, you know, you’ve had this money, you’ve… well, you’ve squirreled it away, you know, what have you done with it?

They came to search my house to see if there’s rather nice things suddenly appeared in my house, like a nice new car outside or something like that. Fortunately for me, there wasn’t, you know, there it’s… but there was very little actually in my house at the time, which did… of mitigating the effect, I think.

‘Cause I think they were surprised at how little there was in my house… a little letters. I had a computer system and a big beanbag. At that time I didn’t have any furniture or anything like that, just at that particular time. I think that helped slightly. But anyway, did prosecution proceedings were the norm?

Adam: How did they search your house? Like they’re not… they’re not the police.

Scott: Well, incredibly, there are three different bodies that have this power of prosecution. In other words, they don’t need to use what we have as the Crown Prosecution Service. What happens is the police gather evidence, they give it to the Crown Prosecution Service, they decide whether there’s a case, and then it goes to court or not.

You might not like that, but some people can usurp the Crown Prosecution Service and take you straight to court: HMRC, of course, and some incredible ancient law. Old Elizabethan law and Royal Mail have also got this power. I think it was because, way back in 1690 or something, people carrying valuables around for others were targets.

So they ended up having their own, not police force, but security personnel. Yeah, it’s kind of gone on from there. And they’ve still got their own security fraud squad, with powers not quite the same as the police, but enough to take me straight to court.

Handcuffs For A Village Shopkeeper

Adam: There was no way out. The auditors and prosecutors from London had already made up their minds. Subpostmasters like Scott, they probably couldn’t be trusted. Why would someone take on a job like this handling all that money? If they weren’t trying to skim a little off the top so they could gamble, or worse, in their eyes, Scott was just another criminal hiding in plain sight, a bad egg in the system, and prosecution was the only way forward.

Scott: Yeah. Well, I… I got charged with five counts of false accounting… that was changing the figures five times in a row, basically. And they were going to… deem me for theft as well. Even though there was no evidence of theft, and we actually had a memo on post office, had no paper saying, after their exhaustive investigations, we find no evidence of theft, yet they were still going to try and prosecute me for that, you know… I went to Chester Crown Court. Handcuffs, everything, you know? Uh, so there we go.

Adam: The story is so unfortunate that I feel like I just need to say it out loud. Scott put everything on the line. He used his savings, his mom’s inheritance that she got from selling her business, and he even took a mortgage on his house, all to invest in this business, which is just something people do to start a business.

Fair enough. But now he’s in handcuffs, and he thought maybe the court would sort things out for him, but in reality, he was up against one of the oldest and most powerful institutions in the UK. The odds were stacked against him. They had their own prosecution branch, and from here, things only got worse.

I get it. I’d be hopeful. If I were Scott, I’d probably think, you know, what’s the worst that could happen? Maybe I’ll have to sell the store, but at least I can move on from this nightmare. I thought this was gonna be my job, but now I just wanna get out of it. But in fact, it didn’t work out that way. It got much, much worse.

Where Ghost Money Goes To Die

But what had just happened? Where was this money actually going?

Let’s start with the stamps. The first big blow that Scott took, imagine it’s 2008. It’s the end of the day. The receipt printer is still warm. There’s a line of rubber bands on the counter from where Scott’s been bundling up the stamps. This is the end of day tidy up time. Count out the stamps in the drawer. Tell the computer what you got. Make sure all the numbers line up on the screen.

It’s a simple form. You know the amount of stamps in. He scans the tray, he taps enter, the screen hesitates. Maybe the computer freezes. Maybe it does that sometimes. So he hits enter again, because that’s just what you do.

But here’s what I think happened. The system would freeze, and then it would repeat. It would play back your key presses so that one stock-in entry turns into two. The screen didn’t warn him; the screen was frozen. It just added another batch of stamps to his ledger.

So that means in the drawer there’s what he actually unpacked. There’s today’s stamps, but in the computer, there’s today’s… twice.

What that means is at night’s close or the next day, they think he’s holding more stamps than he does, more than physically exist. It’s not missing cash, exactly. It’s just ghost stamps that the system insists should be there, or the money for them. And that’s how you wake up owning £1,750 in stamps that you’ve never seen.

It’s not that Scott skimmed anything; it’s because the counter said hit enter and he did, and the screen hiccuped, and the software created a version of the world that didn’t actually exist.

Now, those bigger discrepancies, I have some theories too for how they could start. It’s the same type of glitch, just on a larger scale. If a builder brings in £2,500 and Scott enters it in and the cursor hesitates, so he hits enter again, it’s a busy store, he’s gotta move on. One real deposit now becomes two entries, and then an hour later, a cafe owner comes in with £1,500 to deposit.

Same pause, same double enter, and no one would notice this in the rush. That cash is there, it’s counted, and it’s real. But at closing, it says that there’s £4,000 more cash in than is actually in the drawer. It’s just two ghost deposits, right? It’s not theft; it’s just buggy software.

It’s not innovative. There’s a system of checks and balances that should be in place, but the reason things failed here has to do with how this software was built.

How A Failed Project Became A Weapon

Adam: In the nineties, the UK government set out to modernize every post office counter. They wanted to get rid of old paper benefit books, and they wanted to switch to a card system. So they brought in this company called ICL Pathway to handle both jobs. They’re gonna put a computerized point of sale system in every branch, in every post office store, and they’re gonna move all their benefits payments online.

There’s two pieces to the system: the post office and the benefits. The benefits part gets cut. The whole thing doesn’t go well. There’s delays, there’s fights over cost, there’s changing requirements, but somehow the counter system survives, and that’s the system that’s running Windows NT at Scott’s office.

The project at the scene is a huge failure, but they can save this post office part, and maybe things will be better. Newspapers write up stories about all the wasted money of this project, but it still rolls out. And even without the benefit cards, putting computers on every counter still feels like progress.

It sounds like a sunk cost problem. They put all this money into this failed project, and surely they can save some of it by rolling out the small piece of it.

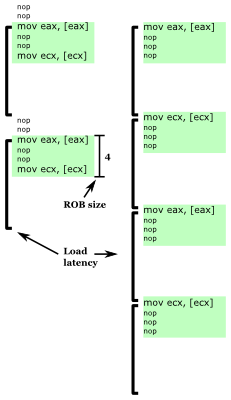

And because this was built in the nineties, you know, it has dial-up modems and it has unreliable connections and thousands of tiny shops that need to communicate to home base. So the system was built offline first. Every branch got their Windows NT box, and it was hooked up to scales and a barcode scanner, and a receipt printer and a messaging layer that was called Riposte.

So if the network went down, you could still serve customers. Transactions just queued up locally. And then when the internet was back, the data was synced.

For the time, that was a smart trade-off. The internet was not reliable, but it was a trade-off. When you have this sort of store-and-forward system, your truth comes from a pile of queued messages on various machines, and they can get delayed, and they can get retried, and they can even get replayed.

These are just the problems of a distributed system. Most days, everything works fine and the ledger looks clean, but every so often, maybe it doesn’t work out.

Most days, you never notice any of this. You sell stamps, you pay out pensions, you take deposits. The cash drawer has the money in it, the terminal has its numbers, and at the end of the day, those two sets of records are supposed to match up.

But when they don’t, when you’re left staring at two realities—what’s in the till and what’s on the screen? How do you reconcile that? You might think like Scott did, but the numbers have to balance out eventually.

If a deposit got doubled somewhere, someone should end up with twice the money in their account, and that should be flagged. There should be discrepancies that show up somewhere. Double-entry accounting is supposed to catch these things.

You can’t actually just create money out of nowhere.

But I actually looked into this while the ledger system that tracked what Scott made and owed each day was offline. First, the banking transactions were live in real time. They were real-time communications with the bank.

So it’s very possible the money was deposited once, but because of a double press or a network hiccup, there were two records in Scott’s system for it.

And somewhere these numbers must get reconciled. The money transferred into somebody’s account, you know, should line up with this aggregate of data across all these post offices.

So, in fact, somewhere it should all shake out and even out, but not in any place or timeline that actually helps Scott.

Most days, the software worked fine, but it turns out there were plenty of known bugs, enough to cause real mistakes. And behind the scenes, people at Fujitsu were scrambling to keep things running. They were patching issues, they were finding ways to update the ledger, forcing the numbers to add up and be correct.

Scott didn’t know any of that. All he saw was the computer telling him that he should have money that he did not, in fact, have. And then the auditors seeing the same numbers and jumping to their own conclusions. Hey, here’s a small-town guy who’s stealing from us. Let’s make an example of him.

If you’re from the UK, you might’ve heard parts of the story before, maybe not about Scott, but about the 13 postmasters who took their own lives after facing similar accusations.

Scott didn’t take that way out, but his life was definitely turned upside down by all of this. What about the software itself and the people who maintain it? How could an organization that took this failed software project in and pushed it out and was constantly fighting bugs and drowning in errors turn around and aggressively prosecute people who were affected by those bugs?

The Bug They Named And Never Fixed

Let’s rewind.

After Horizon was created, but before it got Scott put into handcuffs, before it got him splashed across papers as a thief, the company that created it was acquired by Fujitsu, and so Fujitsu held the maintenance contract for the software.

Scott had no idea, but Fujitsu engineers had already had a name for a bug that seemed a lot like the one that was draining his account. They called it Callendar Square after a Falkirk shopping center where they first spotted it on September 15th, 2005. A sub-postmaster at the Callendar Square post office tried to move stock from one counter to the safe, but the transaction just seemingly disappeared. Wanting the books to balance, he tried it again.

But what he didn’t know is Horizon’s Riposte messaging layer had frozen. It had a message timeout waiting for a lock, and when the terminal was restarted, when the lock was finally cleared, it replayed that queued message. Suddenly, both versions of the transfer showed up: two transfers in for a single transfer out.

In double-entry bookkeeping, which I’ll touch on at some point, for every transaction, there is both an in and an out. This is a careful check on things. But on paper, this branch suddenly had a surplus in one account without a matching shortfall in the other. Because of that, the operator, the sub-postmaster, was on the hook to repay the difference. Fujitsu logged this failure as PEAK PC0126042.

A few days later, it happened again, and then it was given a different number, and both incidents landed in their internal error logs. So they put the incidents in their known error logs and gave advice to the support people at the post office: if somebody reports this problem, tell them to reboot the machine, and whatever they do, don’t enter it again.

Internal emails showed that Fujitsu admitted this lock bug had been showing up at a number of sites most weeks going back as far as 2000, but the sub-postmasters were never warned. Fujitsu just kept the known error log to themselves.

So if this is what happened to Scott, and if he managed to reach the post office before a restart or whatever occurred to get the double posting, the staff there wouldn’t necessarily know what to tell him. But it’s wild that the folks running the Horizon system already knew this bug inside and out by the time it happened to him. But for the actual sub-postmasters dealing with this, they were kept totally in the dark.

Vanishing Money Bags And Double Books

Adam: And that was just one of the issues, right? There was another one called the remming out problem: remming out being short for remitting out the end of the day routine, where you’ve got too much cash on hand, and you seal the extra money in pouches, log it into the system, and then a van comes and picks it up.

Basically, you’re moving money from cash on premises to cash on transit. Right? You don’t want too much around so that you don’t get robbed.

You can imagine, an end of day, Scott, on a busy pension day, has too much cash in hand, so he follows the routine. He prepares these pouches, each have 10,000 pounds in them and 20 notes. Each bag gets sealed, and it has a barcode on it, and in Horizon, he’s supposed to enter that. He has this 10,000-pound bag, and then he has the second 10,000-pound bag, and it should subtract 20,000 pounds from the branch’s holdings and add 20,000 to the pouches ready for collection.

But this remming out bug, which sounds really bad, if you did two bags and they had the same amount in them, Horizon only subtracted the first one from the branch’s holdings, even though both bags showed up going into the van.

In other words, the van would get their $20,000; but the branch would say it had only taken out 10,000.

When people talk about balancing the books, this is what they’re talking about. Both sides need to match. You can’t take out 10,000 here and deposit 20,000 over there. It doesn’t make any sense, but that was the bug. Both bags left the branch. Both were in the van, but the system acted like only one had gone.

And so on paper, it looked like at the end of the day, there was 10,000 pounds of cash missing. It’s like the ghost stamps; only this time, the numbers are much bigger.

That is the reason double-entry accounting exists. Every transaction gets recorded twice, once as a debit in one account and once as a credit in another. And those two need to balance. If they don’t, you’ve either created or destroyed money out of thin air.

And this isn’t a new idea, right? The idea of recording everything twice goes back to merchants. In Renaissance Italy, in the 1400s, they were using double-entry bookkeeping.

If you’ve ever written code, double-entry accounting might feel familiar, right? It’s basically a 15th-century version of like a two-phase commit. You can’t close the books until both sides acknowledge the change has happened.

If you have two physical machines separated on a network and you’re taking something from one and moving it to the other, both sides need to confirm that they’ve gotten that change or it didn’t actually happen.

If one side never acknowledges, or if things just hang, then it doesn’t count. Is it also kind of like test-driven development? Right? Every code change needs a matching test. One side needs to match the other.

If the logic in the test or the logic in the code you added is incorrect, something will fail, and that’s a sign you need to figure out what’s going on.

There’s so many metaphors for this. The other way to think of it is like a checksum, right? If a checksum doesn’t pass, then the data’s corrupted.

But really, the system should not allow you to have a debit in one account that doesn’t match a credit in another. It’s just a simple integrity check.

And instead of investigating and blaming the system for breaking basic accounting rules, somehow the finger gets pointed back at the sub-postmaster.

The remming out bug, and in February 2007, Fujitsu reviewed this bug, and they found internal notes showing 49 branches were hit that month.

And maybe because this one is obvious and doesn’t balance, they did remotely access some of these branches’ machines and tried to fix up the ledger entries. We don’t know if Scott’s branch was one of them. We don’t know if this was the bug he encountered. The details just aren’t available.

But what we know is that in some cases, Fujitsu was working behind the scenes to try to correct these errors without telling the contractors like Scott or either telling the post office itself what was going on.

And there are plenty of other issues.

And honestly, we’ll never know what really happened to Scott because no one bothered to look.

The Support Line From Hell

Adam: The problem was there’s so many layers. There was the software company doing the maintenance fixes.

They built the software. They don’t wanna talk about bugs. There’s the support people at the post office, and they’re overwhelmed.

And that’s why the first time the numbers didn’t add up, Scott did what anyone would do. He called for help.

And he gets the cue music, and then he gets an unsympathetic support worker who’s working through a script. Check the till, recount the stamps, maybe power cycle things. Have you tried closing the session and then reopening it? It’s hard to say whether the agent is even really listening or just working through a script.

But one thing’s for certain, right? He reminds Scott, the contract says that the branch must balance to roll forward. If Scott can’t fix it, the difference comes out of his pay. It’s in your contract, sir. You can spread it over two deductions if that makes it easier. Scott hangs up feeling small, not just that they’ve taken money out of his pocket, but that they don’t trust him.

If the computer says the stamps are there, then they’re there. If they’re missing from his drawer, then that’s on him, so he pays right in that first case. He pays that 1,750, and he tells himself it’s just a glitch and it’ll work out, and that’s fine. This is his business. He’s excited. But then, yeah, a few days later, the numbers don’t add up again, and the gap’s even bigger.

I’m just playing this back in my mind, right? If he admits the shortfall, then they’ll take the money right away, and maybe he won’t be able to make payroll, or maybe he won’t be able to pay the lease.

So he’s a businessman. He does what he needs to do to keep the business running. He forces the period to roll over. He tells the system that he has the money. He tells them what it wants to hear, just to make it through the night, make it to the next day. And that desperate entry to move forward is what was later called false accounting.

That’s what got him put in handcuff. That’s the moment where the system of prosecution, decided that he was the villain and he was someone to blame.

The Experts They Hid From You

But here’s what’s interesting to me. Right behind that maze that Scott couldn’t see, there was real experts. The ones who could spot a software bug, they were just hidden inside Fujitsu’s back office, and they were trying to fix things. Maybe they were working very hard. You know, they had a list of known errors, but those never made it out.

And if the problem you had looked like something in their error logs, support might notify them. Maybe it would quietly get fixed. I don’t know. But if it didn’t, or if no one checked.

Then you’re stuck. And Fujitsu was swamped with these bugs, but they also kept them under wraps,

this list of known errors. They kept that as an internal list, they never shared it with the post office support at all.

So it’s not just the software thing, about organizations and culture. The post office treated every shortfall as a personal debt against the sub-postmasters. You either had to pay up or they took the money from you.

It seemed like there was some sort of quiet disdain where this big institution looked down on these village shopkeepers, like people in charge in London while the subpostmasters are working in their villages.

But there was, at least in theory, another option. If Scott had known the right phrases and if he was willing to lose pay and to not just forcibly rolled it over, he could have refused to roll over the period. He could have stood his ground not entering anything, but not accepting their numbers.

I don’t know what would’ve happened then, but what I’m imagining is. Maybe he eats the cost on that first time,

but the second time he goes all forensic accounting on them. He starts writing down every transaction. He starts taking screenshots, who pressed what, what happened where he starts a formal dispute process with them, says that he wants to report a system defect, is very clear about his words and is very demanding of an audit before any penny is taken from his pay.

If he had known that the software had so many issues, I mean, which of course he didn’t, and if he had taken the time, maybe he could have shown them

or maybe not, but maybe he could have written to his mp. Maybe he could have got a lawyer to send them a letter. Maybe just maybe that would’ve pushed them to look into it to get off the script, and then somebody would stop saying, it’s your problem. If the numbers don’t balance, you just need to pay. If he could get people’s attention like that, maybe he could get the issue escalated, maybe then Fujitsu would’ve stepped in.

They would’ve taken a real look. Maybe they would’ve straightened things out.

I do think it’s possible,

but think about what this really means. scott’s gotta operate this business. And all of a sudden now he’s got to be a legal expert, be a forensic accountant, be a site reliability engineer, and use some sort of bureaucratic kung fu to get people’s attention while customers wait in line and wanna get their pensions or wanna get their packages, he’s supposed to risk his payroll and his reputation and all this hope, uh, on the fact that he could make some change happen.

And there were 14,000 subpostmasters

and many of them were having problems. So it’s a lot to get above the noise when you’re contacting the support line, and their job is to get you off the line and move on to the next one.

And Scott didn’t have a map to all of this. He didn’t know that all this was going on. All he had was this useless support line and his lease payment and this cash drawer that never matched the numbers on his screen and these people telling him he had to pay. The next time he just entered what the computer wanted him to so that he could open up his shop and he could do his business.

It’s a choice that’s completely human and totally understandable, and one that would get him arrested.

I think it’s interesting, sad, but interesting how you can look at the details of this and see how it ended up where it did.

Why Big Government IT Always Goes Wrong

Adam: Horizon is a textbook case of how big software projects go wrong. Yes, the goal was to modernize every post office counter and replace benefit books with a payment card. But government projects like this have a bad track record. The bigger the project, the lower the chance of success. And this project was one of the largest IT contracts in European history.

As I mentioned, on paper, this project was supposed to do two things: the welfare payments and computerize the accounting. But that involved two different agencies and two different sets of requirements, and it all was in one contract, and it went sideways.

Patrick McKenzie, patio11. He’s covered stories like this before. He says government software projects fail for pretty predictable reasons.

He says, all systems reflect the culture they are created in. No system of importance can be accurately described without the context of the culture that created it.

In other words, the institutions and the culture of how things are done are the hard part of government software, not the technical details. Maybe they could have straightened out the technical details, but things were already a tangle. There was overlapping institutions and there were conflicting incentives between the software company and the subcontractors and the post office.

And everybody had a contract, and everybody was working to contract.

And when you build software to contract, you get something that hits the check boxes that has the process, but maybe is not working.

Because the problem is that government procurement processes don’t reward working software. They reward compliance and following the RFP and audibility. It’s like ordering a car with a parts list. You can check every box for all the pieces of a car, but end up with something that doesn’t actually get you anywhere.

And then, because institutions hate admitting failure, they basically can never admit failure. The easiest path to salvation when the welfare project failed was just turning this whole thing into the Horizon Postmaster system.

Big Bang Rollout, No Safety Net

Adam: This software project is tragic, but it’s also kind of fascinating. There are just so many things that went wrong, and I can’t possibly go over everything that went wrong here. As Patty 11 said, it’s more cultural than being a specific person who made a specific error in a specific place. But for one interesting example, imagine you’re gonna roll out this system.

It’s a nationwide, offline, first point of sale system with active users across every small village and major city in all of the UK. In other words, it’s a lot, right? And there are a lot of ways to roll out a system like this. If you’re forcing the use of a failed project to save face, you should consider rolling it out piecemeal, doing a canary deploy of some sort, or implementing some sort of gated rollout. Try to use the software in a small number of post office owned stores.

Keep a very close eye on it in small numbers like that. Maybe just one slow store to start, but really spend time and make sure each issue is resolved and investigated. There were actually 115 post office stores that were owned and operated by the crown. So that is a feasible plan. Just do those 115, investigate every problem.

Maybe run the system side by side with the old system and see how it lines up. That’s something I would suggest. But the institutional reality of large government organizations pushes projects of this scale towards big bangs. The software is done. We had checklists, and all the checks have been checked.

No one is gonna raise their hand to say, “Oh, actually there’s this problem over here.” So when rollout started in 2000, and these Horizon terminals, these Windows and T boxes were bolted to scales and given barcode scanners and receipt printers, it was rolled out to all 14,000 village post offices all at once.

And I am assuming, because before rollout, we decided that the software was correct and perfect for the task. I’m using air quotes here, but you probably can’t see ‘em. But because we decided it was correct and perfect, except for some known issues that Fujitsu is keeping to themselves, there’s a simple rule, right? If your books don’t balance, it’s because of you and not the software, and so you must pay the difference.

And that’s why, as Scott was taking over his post office shop, Horizon had all these failure conditions perfectly lined up, all the things that patio11 warns about. So by early 2000, as Scott was taking over his village shop, Horizon had all the hallmarks that patio11 warns about: a contract that’s optimized for process over getting the right outcome, lots of people who can veto things, but yet no single accountable owner, an architecture that amplifies small glitches into accounting discrepancies, and an institution that’s unwilling to admit that there might be faults.

So when those glitches hit, the entire weight of the institution tilted towards prosecuting the subpostmasters because to admit otherwise would be to admit that the project itself was a failure, right? That so much money was gone, that was wasted. Or as Patrick McKenzie puts it, risk rolls downhill. A ledger goes wrong, and the people with the least power end up holding the bag because they can’t prove who’s at fault.

That’s the interesting thing to me. When Scott picked up the phone line for help, he didn’t reach the people who actually built Horizon. He got the post office support, and their real job wasn’t to escalate bugs. Their job was to keep things from ever reaching Fujitsu because of contracts and processes, right? Because sending things up to Fujitsu had a cost.

And it had all the overhead and painful machinery of a giant government vendor relationship. So the defaults were simple, right? If Horizon glitched, that was Scott’s problem. If the till didn’t balance, he had to make good. Small issues never became system bugs; they became debts because nobody else wanted to admit there’s a problem. Fujitsu wasn’t gonna eat the risk, the post office wasn’t going to eat the risk, so all the risk just rolled down onto Scott.

Guilty Plea Or Prison Time

Adam: And that’s why things did not go well for Scott, right? He ended up in handcuffs and he was put in front of a judge in court.

Scott: Yeah, I naively thought, well, I haven’t taken any money. I haven’t stolen anything. I haven’t done anything wrong, really. If I go to court, the legal system will back me up.

But, uh, it turns out it’s not quite like that. So I had to plead guilty to false accounting; otherwise, I would be going to prison because the judge would’ve just said, well, you did do false accounting, you know?

It was like, oh no. You know, so another lesson there, a bit naive. I really did think that it would come to my aid in the end, where it didn’t.

So if you plead not guilty when you are guilty, you don’t get a suspended sentence. So I had to plead guilty to keep myself out of prison.

So off to court, I get prosecuted, I get a prison sentence. I didn’t actually go to prison, but I had a suspended prison sentence, which meant I couldn’t travel; I couldn’t say I couldn’t come to Toronto.

Adam: And also because his store is in a small village, his arrest was front-page news.

Scott: I’m on the newspaper. I mean, the newspaper is like this… “Crooked Postmaster, a dishonest postmaster.” You know, so what? What are people gonna think about that? Luckily, the people that knew me knew something wasn’t right, but the wider public that knew me, you know, from having this post office, they didn’t know, did they? They presumed I’d been to no good.

Adam: Then the next problem, Scott can’t operate his store anymore. He doesn’t have a license to operate as a postmaster.

Scott: Yeah. Well, that’s right. I owned the business. We had a loan taken out against our home, which was work. Everything was working fine up until this point. And suddenly now I’ve… the business has been closed, but I’ve still got the loan against it to pay. But the shop closed down now and the post office closed down.

I avoided bankruptcy somehow. It is a long story, but I managed to avoid bankruptcy, which can get you out of debt. But if it means a decade of, you know, trouble… you can’t even get a bank account and things like that if you’ve been made bankrupt. But anyway, I avoided that and somehow he managed to hang on to our home and get rid of the lease from the shop and everything. But it was just a disaster. You know? I was in debt. I had county court judgments against me for suppliers that I couldn’t pay. Not large amounts, but it was just embarrassing.

You know, I’d had a great relationship with all these suppliers for years, and now I can’t pay ‘em, you know, and they’re having to take me to court and everything. It’s just so embarrassing.

Adam: And was this hard for you? Like, mentally, emotionally?

Scott: Yeah, it was, yeah. Yeah. It really was. I mean, you just felt down, you felt when you walked around your hometown that people were going, “Oh, that’s that guy. It’s that guy there. We read about him.” You know, even if they weren’t, you felt… you felt like that. And, uh, so wandering around going, going and… socializing, you and you’re always wary of how people looking at me.

This goes on for quite a long time. It’s probably irrational ‘cause as you know, you… You know, you’re in the news for a day and people generally forget a thing, but I don’t know if they forget about that kind of thing. So, you know, it’s irrational. But this is what… this is the kind of anxiety that it causes in you that goes on for quite a long time, actually many years.

I couldn’t get a job ‘cause you know, I dunno what it’s like where you are, but you have to… on job applications, you have to say if you’ve got any criminal convictions. And, uh, if you say no, you committed another offense. You know? So you have to say yes and, uh… Come on.

It’s human nature on job applications. If people have got a current criminal offense, they’re gonna be a standard, much less chance, aren’t they being employed. So that was the position I was in. So I’d gone from earning pretty good money doing this business to state benefits, unable to find a job, for three and a half years.

And I got an 8-year-old daughter at this time, isn’t it?

Thirteen Took Their Own Lives

Adam: For years, the post office blamed Scott for all those losses, but the full story only came out much later, 20 years on when a public inquiry finally made all the details public. Everyone finally saw that people like Scott were broken by the very organization they wanted to serve.

For most people in the UK, Scott and the other subpostmasters were the face of the post office. They were the friendly person helping you with your pension statement, selling you your stamps, weighing your Christmas parcel. Those were the people you trusted.

They’re the last ones the organization should turn against because they’re the heart and the face of your business.

Scott: I dunno how they could sleep at night. I dunno how they could go on holiday with the families, knowing that this is going on, and then we would say nothing about it.

But in big corporations, it appears that there’s this kind of groupthink mindset, you know, that people just do not rock the boats. They just keep their head down and carry on despite knowing what’s going on.

When You See Something, Say Something

Adam: It’s true. I have worked on similar software projects before. I worked on something that was not unlike Horizon, but for a big Canadian government project. It didn’t go well. It didn’t go as badly as this, but that’s not really saying much because, I mean, this went incredibly badly.

But that’s what makes this so interesting for me. Because I can understand what it’s like to be the people at Fujitsu or, you know, what it’s like to be the support person. But I wanna say, I think we all have a duty to be good citizens to the world, even in our commercial endeavors. We need to sometimes take the corporate blinders off and see what’s going on in a wider context. It’s easy in an organization to feel compartmentalized and that you don’t have a role in the things that you’re doing, but you do.

Right? And there was, in fact, a whistleblower from within Fujitsu, and he was helpful to unraveling this whole thing. But there should have been more people coming forward. There should have been more people trying to resolve things. And there should be more in the future if your rideshare company is quietly shorting drivers on their pay.

And you know about it. You know, speak up, tell somebody. Tell me. When you notice something at work that feels off, when you realize your organization might be in the wrong, don’t just ignore it. Take a closer look. See if there’s a way that you can do the right thing, even if it’s not your job description.

It’s hard to do. I get it. You’re busy. But if someone is going to jail because of a software bug, or losing their health coverage, or not getting paid for their work when they really need to get paid, then that matters because these risks often roll downhill. Gig workers are hit the hardest, and they’re the least able to shoulder these burdens. So, if you see something, say something.

That’s why I wanted to share this episode. Doing the right thing isn’t easy, but it is possible. Thankfully, though, the UK, I think they may have learned their lesson.

Scott: I think that’s one thing that’s gonna come outta it, which will help future. It’ll stop the… the… and people just saying, “The computer says this, you’re on it.” And people go into prison, you know, so, uh, it will stop that thing. But as for software companies, they know there has to be a duty of candor somehow.

They can’t… they can’t load the risk of… of their systems onto other people, which is what they did. Every system’s got faults. I mean, so what? But if they flagged it up on your screen that there’s a bit of fault, there’s been a bit of a discrepancy in your branch for putting it right.

You just have faith in the fact that this system’s constantly being, uh, you know, uh, looked after, but instead there was none of that. And off… off prison we went, you know, that kind of thing. It all seems so, um, Victorian now, uh, already, you know… that that’s how they treated people.

So, I dunno how it’s gonna work for the ordinary people in the future, but, uh, yeah, it is good. Things are gonna change. Let’s see if it changes to the… for better protection.

Twenty Years Later, Still Waiting

Adam: For Scott, things still haven’t worked out between 2017 and 2019. Uh, 555 subpostmasters, of which Scott was one, sued the post office, and they won. But after legal fees, which ate up like half the money, they each got about 20,000 pounds.

And Scott, along with 62 others, didn’t get anything at all because they had horizon-related convictions. They were excluded from the payout because they had pled guilty. You plead guilty, you get nothing. But then in 2024, a TV drama about the scandal caught the attention of the Prime Minister, and now new legislation is probably going to overturn Scott’s conviction and help him get compensated, but it hasn’t happened yet, right?

These things move slowly, and it’s been over 20 years, right? We started back in 2005, with Scott sitting in a parking lot counting customers back then. He was excited about the post office, but now he feels completely different.

Scott: Oh yeah, I don’t go. I don’t even like the vans going fast with the sign on the side, you know? I can’t even stand to see that. I’ll turn away from that, you know? So, no, I’ll try my best not to go in.

But I can’t remember the last time I went in. Actually, I think I did have to go in one at some point in the last 10 years. But it’s been a long time. I won’t go in if we can help. I hate… I hate the thoughts of it really.

The Story’s Not Over

Adam: That was the show. Thank you to Scott Darlington for sharing something that, I hope most of us will never have to live through. His book, Signed, Sealed, Destroyed, tells more of that story. It’s a self-published book, and I loved it.

I dunno if you can tell, but I can’t say which specific Horizon defects affected him. What you heard here is kind of my reconstruction based on looking through all the documents. Because of the inquiry, there was a giant trove of documents released, and I found it interesting to dig through them and to try to imagine what this was all like and what it was like to be an engineer or a support person at Fujitsu or at the post office.

I know in situations like this, accountability is diffuse, and that’s why these bad things happen. But many people were in positions where they could have looked around and they could have thought something has gone terribly wrong. If you wanna see the story from another angle, check out Mr. Bates vs. the Post Office. It’s a dramatization of some of the key events in the scandal. I have not watched it at all because I heard about the story, and I kind of wanted to pursue my own path. I wanted to talk to a victim, and I wanted to dig through the documents, which is something I like doing. Maybe I’m a bit of a weirdo, but I’ll probably watch it now, and it’ll probably make me think of all the things I should have done to make this episode better.

Also, a huge credit to Computer Weekly. They are a long-running online publication for IT professionals, and they broke this story for years. They covered the failures of the Horizon system in more depth than any mainstream outlet could ever get away with. And because of that, and because of postmasters who refuse to give up, there was this inquiry, and things did get resolved. But yeah, thanks to the team at Computer Weekly, that is incredible work.

And because Scott is more than just, you know, a downtrodden victim of the post office, here’s some music. I found Scott performing with some rowdy people yelling in the background. I dunno who owns this music, please don’t sue me. And until next time, thank you so much for listening.

Hello,

I make CoRecursive because I love it when someone shares the details behind some project, some bug, or some incident with me.

No other podcast was telling stories quite like I wanted to hear.

Right now this is all done by just me and I love doing it, but it's also exhausting.

Recommending the show to others and contributing to this patreon are the biggest things you can do to help out.

Whatever you can do to help, I truly appreciate it!

Thanks! Adam Gordon Bell

.png)