Slack got 15K DAUs in 6 months & had an internal built-in invite loop. Dropbox grew 100K → 4M users in 15 months & had a referral (viral) loop. But your product will fail with these viral loops.

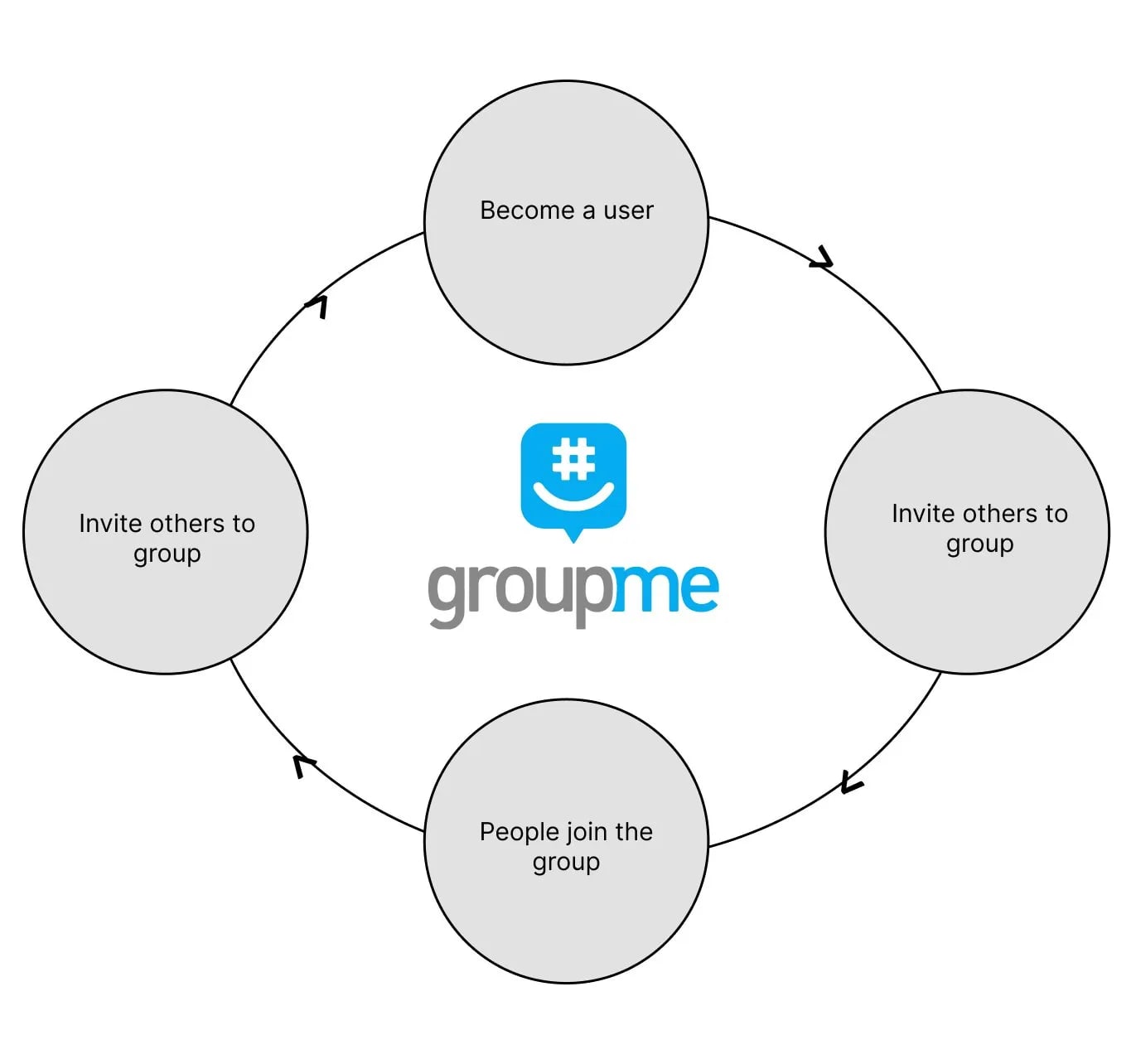

We've all heard and drooled over stories of startups like GroupMe, which experienced huge viral growth within their product and sold for $85M only 370 days after launching.

But stories like these, told in one-line headlines & startup lore, tend to leave out all the nuance. They make viral loops sound like magical cheat codes. Plug one into your product, and boom - hockey stick growth. But that’s rarely how it plays out.

The point is not that these stories are false, but they are just half-baked. I’ll explain.

See, a big part of this conversation boils down to a few pointers (TL;DR):

The reason companies like Slack, Figma, etc., saw such massive success is that their viral loop was deeply embedded in how their product worked. It came from their product’s native usage. You literally can’t use Slack without your team. You can’t collaborate on Figma designs alone.

These loops were part of the core UX and value proposition, and they made the product more valuable with every new user. That’s what made it viral, not the other way around.

A viral growth loop analysis of TikTok, for example, will explore its discovery algorithm, viral challenges they did, and how users share their TikTok videos across other social media platforms. However, if that analysis ignores the fact that ByteDance spent $1 billion on paid advertising to promote TikTok solely in the US in 2018, then it is incomplete.

The source of traffic and the actual attribution are crucial for understanding the success of viral loops. Most breakdowns do not account for the money spent on PR, Ads, Partnerships, Conferences, and other linear growth channels that contribute to the viral loops.

Acquiring new users through incentivising your existing users is always easy (people love free stuff), but it is extremely hard to retain those users if your product is not good.

A professional networking company, BranchOut, is a great example. They went from 1M to 14M MAUs in 5 months using a viral invite loop. Then tanked back to 2M just a few months later, as users couldn’t find a clear value prop and churned.

And if a company does not really understand the what’s, the how’s, the why’s, and the where’s about the segment they want to target, they won’t be able to incentivize their users effectively. You can not deploy or rely on a viral loop without a definitive Product Market Fit.

Not all growth is good growth. You don’t just want more users, you want the RIGHT kind of users. Your loop needs to bring in qualified leads, people who resemble your ICP and can get real value from your product.

Otherwise, you’ll grow topline numbers while quietly destroying your funnel. This kind of growth hurts more than it helps.

Say you run a project management tool built for startups. You launch a viral loop that goes wide, offering $100 in BTC for every referral. Suddenly, college students, bloggers, and small hobby communities start signing up just for the reward.

Now, your signups spike. But your activation rate tanks because these users don’t need your product. Your overall retention drops. Your support team gets flooded with irrelevant tickets. You start optimizing for noise, not signal. And worst of all, your real users start getting lost in the clutter. You waste resources chasing growth that was never going to convert.

Ultimately, every channel decays. That’s the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs.

No matter how viral or beneficial your growth loop is, it will always have a ceiling in your market. Eventually, it will stop giving you that exponential, super-linear growth.

The truth is: great companies treat every growth loop as a temporary advantage. They constantly test new ones before the old ones die. That’s the only way to stay ahead of decay

What works today won’t work tomorrow. Banner ads went from 78% CTR in 1994 to 0.05% by 2011. Saturation kicks in and performance drops.

Now let’s go deep into it. (yea sure, that’s what she said!! 😉)11

Firstly, for those who don’t know:

A viral growth loop is like a flywheel. One user brings in more users → those users bring more → and so on.

Example:

I’m building SignWith - a simple pay-per-doc e-signature tool.

Let’s say user A uploads a doc & sends it to B, C, and D (non-users). They sign the doc → they see it’s via SignWith → they like the experience → C and D decide to use it and sign up.

So, 1 user → brings in 2 new users. At scale, that would look like: every new user brings in 2 more. The loop compounds. (Super hypothetical, but you get the idea.)

Now, in SignWith’s case, this is a passive loop; it happens as a side effect.

Slack, on the other hand, has an active loop. You have to invite your team to use it. You can't use Slack solo (mostly).

Viral loops are actually way older than you can imagine, with some of them appearing in the form of chain letters back in the early 1990s. (search it up!)

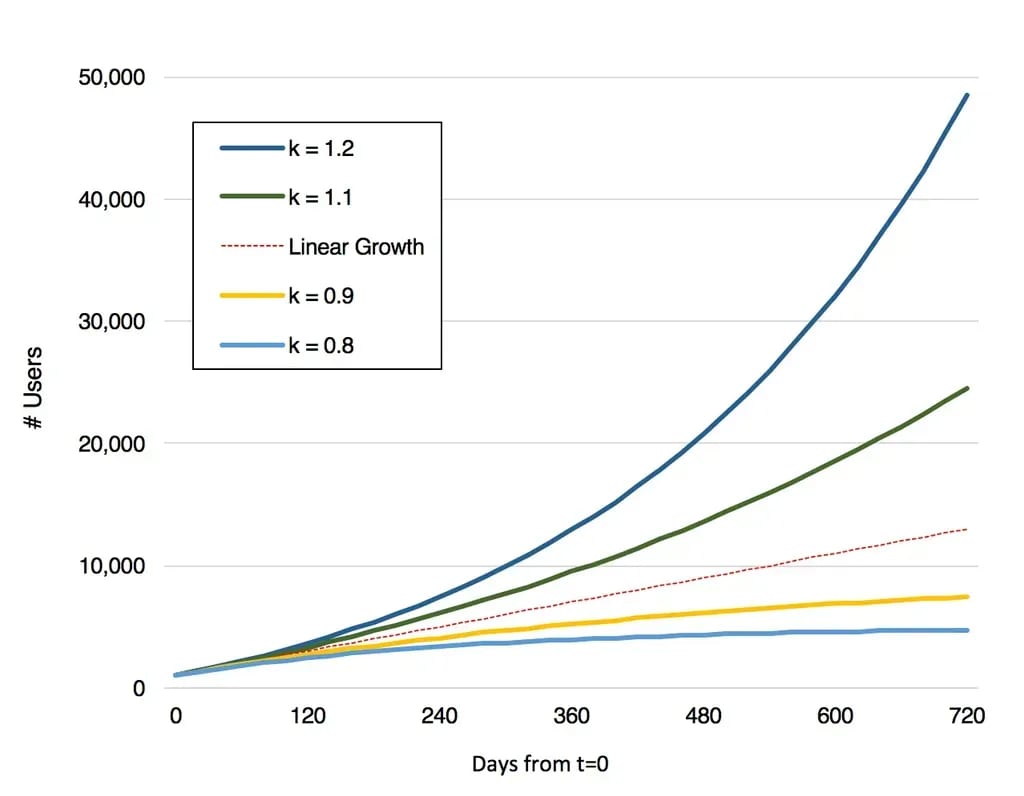

This is where the concept of K-Factor comes in - it is used to calculate how much virality your growth loop is getting you.

It basically means the number of new users a single existing user brings into the product.

K-factor = average invites sent by existing users * conversion rate of invite

Now your K-factor can be

0 → dead viral growth (each user brings in 0 new users)

between 0 & 1 → sub-linear growth (each user can’t even bring one complete user)

1 → linear growth (each user brings one complete user)

>1 → Super linear, exponential growth (each user brings more than one user)

Ideally, your K-factor needs to be >1 to build an exponential growth flywheel. But that rarely happens.

And people think these loops depend on many users bringing many users (M to M) into the product. But in reality, it’s more like a few highly influential users bringing in many users (1 to M); the rest of the other users do not exponentially impact the flywheel.

Now, you’d think if your k-factor is >1, you’ve built a solid product, or it’s giving you solid growth. But sorry to break your bubble, it does not necessarily mean that.

See, k > 1 only tells part of the story. It tells you that, on average, each user is bringing in more than one new user. Sounds great, right? But here’s the catch: how fast they do that matters just as much, if not more.

That’s where the concept of viral cycle time comes in. (New concept, I know! But did you think it’s going to be simple?)

Let’s say your k-factor is 1.2 - cool. But if your viral cycle time is 60 days (meaning it takes ~2 months for a user to bring in that 1.2 users), then your growth might look more like a slow crawl than a rocket ship.

Now you can even flip it. Say your k-factor is just 0.9, but the viral cycle time is 2 days, you might still see meaningful traction because the compounding happens faster, with more loops in less time.

So it's not just the size of the k-factor that matters. It's how often it compounds.

To borrow a finance analogy: it’s not just the interest rate, it’s the number of times it compounds that really builds wealth.

But wait, there’s more!

A high k-factor can still be straight-up misleading if:

Users invite before they find real value. Or maybe when they are forced to invite their friends as part of their onboarding process, to unlock some “great feature.”

They haven’t experienced the core value yet. If they haven’t hit the “aha moment” themselves, they can’t explain the value to others. Their invites feel cold and random. So when new users show up, there’s no clear hook, and they drop off fast.Then there’s the bribe play. You dangle $10, a gift card, or a BTC reward - and sure, people will refer.

But now they’re doing it for the reward, not because they believe in the product. That leads to a whole new kind of mess: invites going to random friends, old contacts, coworkers, and anyone with an email address.

The problem is that most of these people don’t resemble your ideal user. They sign up, look around, and bounce. Your k-factor might look healthy, but your funnel’s filling up with people who were never going to convert.

In other words, k-factor> 1 doesn’t mean your product is sticky. It just means users are capable of inviting others. Whether that turns into lasting growth is a whole different game.

But now you might come at me and say, “But Morning Brew did it, right?”

They ran their referral program and gave away a phone wallet for 15 referrals, a t-shirt for 25, and a sweater for 100. Classic bribe play. It shouldn’t have worked.

And yet, it did.

So the thing is, Morning Brew grew organically via word-of-mouth for years before an official referral program was ever put into place. Their readers were already organically sharing the word and getting new people to signup, they just escalated that behaviour with an extensive reward based referral program.

They didn’t launch rewards and hope people loved it. They had a product people already loved and already shared . And with smart selection (stickers cost ~$1.25 for 5 referrals; swag tiers under $2–$5 CPA), they made referral acquisition cheaper and stickier than ads.

And that’s the real lesson here: A viral loop doesn’t start with clever mechanics. It starts with a product people genuinely want to share.

So, to figure out how effective your viral growth loop or how useful your positive k-factor is, you should consider all of that.

Now, let’s look at the kind of viral loops that are there.

(There can be more, but these are the ones I’ve seen most often in the wild.)

These loops are native to the product’s utility; you literally can’t get full value out of the product unless you invite others.

Take Slack or Figma. You can’t use Slack without your team. You can’t design alone in Figma. The product only works with collaboration; the loop is built into the UX.

User joins → invites teammates → product becomes more useful → teammates invite more teammates

This is why collaboration loops don’t feel like “growth hacks.” They feel like the product is supposed to be used. And because every new user adds value for the existing ones, retention gets stronger as the loop compounds.

This loop works best when:

The product’s core utility is multiplayer

Value increases with more participants

Invites feel like progress, not a chore

These loops kick in when using the product naturally leads a user to share something with other users or non-users, and that shared artifact becomes the distribution vector.

Think Typeform, SignWith, Loom, or Calendly. When someone receives a form or a signed document, they see subtle branding (“Powered by X”), and they often click through.

That creates curiosity → click-through → potential signup.

This is a passive loop. It doesn’t scream virality, but it quietly compounds over time.

This loop works best when:

The thing users create needs to be shared to fulfill its purpose

There’s subtle but clear branding or a CTA on the output

The experience is smooth enough to make others think, “ah, I want to use this too”

These loops are built on the desire to be seen, entertained, or connected. Users create, remix, or participate in something that’s meant to be seen, and that visibility drives more participation.

TikTok is the most obvious case. Every user post can go viral → that virality pulls in more creators → the loop feeds itself.

But here’s the nuance: TikTok’s loop didn’t take off by itself. In 2018, ByteDance spent $1B on paid acquisition in the US alone. Creators, influencers, meme pages, PR, and algorithmic boosts, all of it fueled the engine.

The product had viral mechanics, but the growth came from distribution horsepower + a perfectly tuned content loop.

This is important: Loops don’t work in isolation. They need fuel.

This is where user-generated content (UGC) gets indexed or shared publicly, and people discover the product while consuming it.

Products like Pinterest, Reddit, and Canva operate on content-driven discovery.

People design things (resumes, decks, IG posts), share or publish them, and that content itself drives new users back to Canva. Same with Reddit, Pinterest, Notion public pages, and Substack:

A user creates content

That content gets indexed via Google or social feeds

Others discover it, click through, and try the product

Notion leaned into this hard with its ambassador and template programs, which amplified this loop via creators and communities.

It’s not direct sharing like social or collaboration loops. It’s based on intent pull.

These loops work when:

UGC content is publicly discoverable

There’s SEO or network effect potential

Your product benefits from mass creation or templating

The classic “refer a friend, get X” model.

Dropbox did it right: they offered more storage, something people already wanted. The incentive was not just aligned, it was embedded in the product’s core value.

Want more value? Invite your friends. Done.

Superhuman created scarcity by making invites feel exclusive.

Morning Brew gave away stickers, T-shirts, and sweaters, but it worked because people already loved the content and wanted to share it. The reward just accelerated an existing behavior.

So yes, incentives can work. But only when:

The reward is aligned with the core product value

The product is genuinely worth sharing

The new users are still your ICP, not just random traffic chasing a reward

One last thing -

These loops can (and often do) overlap.

TikTok = social + discovery (plus $1B fuel)

Canva = discovery + sharing + SEO

Dropbox = sharing + incentives

Superhuman = referral + sharing

Which is why I believe growth is more investigation than execution.

You don’t just slap on a loop. You study what kind of loop your product could naturally support, based on how it delivers value, who your users are, what motivates them, and which channels you can realistically scale.

There are 100s of tactics. Your job is to figure out which 2–3 actually fit your product’s DNA, and go deep on those.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Every viral loop that worked... sat on top of a product that actually delivered.

People didn’t stick around because of clever incentives. They stuck around because the product was good. There was a definitive product market fit.

The referral just got them in the door.

Retention and real value kept them there.

You can’t slap a viral mechanic onto a weak product and expect magic. If users don’t love it, no amount of invites, incentives, or clever loop design will save you.

In short, here’s the pattern most people miss:

The loop was native to how the product was meant to be used

If it wasn’t, the incentive was perfectly aligned with core value (Dropbox = storage)

There was already some kind of baseline growth, paid, organic, or word-of-mouth (you can’t have a viral loop on DAY 1)

And most importantly, the product retained users, it delivered value fast, and kept users coming back

That’s why these loops worked.

Not because they were loops. Because they were loops on top of something great. And that’s exactly why your copy-paste playbook won’t work.

If any of these apply to your product, your loop probably won’t take off:

No Product-Market Fit

If users don’t love your product enough to stick, they won’t share it.

Virality doesn’t save a weak product; it just spreads the mediocrity faster.

Fuzzy or Insignificant Incentives

“Invite a friend and get 10% off after 90 days” is not an incentive; it’s a shrug.

If the reward isn’t clear, valuable, or instant, the loop breaks.

Also, if your audience makes $200–$500/hr (lawyers, consultants, founders), your $5 coupon or extra credits won’t cut it.

You’re offering pennies for their attention. No loop survives that.

Bonus fail: only rewarding one side of the loop (just the inviter or just the invitee).

Bad Onboarding

If it takes 10 steps to activate or 20 minutes to “get it,” your users won’t refer anyone.

People don’t invite others into a confusing mess. They need a “that was smooth” moment first.

No Existing Growth Engine (Linear Acquisition)

Viral loops multiply what’s already working.

If you have no inflow (ads, SEO, content, sales), there’s nothing to compound. A loop doesn’t kickstart growth; it amplifies it.

Single-Player Products

If your product doesn’t get better when others join, people won’t invite.

Collaboration has to unlock value. Otherwise, there’s no reason to loop in anyone else.

Not Everything Is Meant to Be Shared

Some products give users an edge, and they want to keep it that way.

Think traders using a new analytics dashboard, editors sourcing content from a niche tool, or consultants using an obscure product to look smart.

It’s not about privacy. It’s about protecting status, positioning, or advantage.

That’s all. The loop only works if the product does.

Everything else is noise.

Cheers! 🫡

.png)